|

BP-384E

CHIAPAS AND AFTER:

THE MEXICAN CRISIS

Prepared by Gerald Schmitz TABLE

OF CONTENTS THE AFTERMATH AND CHALLENGE TO THE MEXICAN STATE LINKS TO HUMAN RIGHTS – IMPLICATIONS FOR CANADA CHIAPAS AND AFTER:

THE MEXICAN CRISIS

On New Year's Day 1994, hundreds of guerrillas claiming to belong to the "Zapatista National Liberation Army" (EZLN – Ejercito Zapatista de Liberacion Nacional) seized several towns in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. The timing was chosen to coincide with the entry into force of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which the EZLN's masked spokesman "Subcommandante Marcos" (a non-Mayan) called a "death sentence" for Mexico's indigenous peoples. The guerrillas themselves appeared to be mostly Mayan peasant farmers. They were, however, surprisingly well organized and proved able to win some popular and urban support. This manifestation, the most violent in several decades of armed opposition to Mexico's government – denounced by the Zapatistas as a "dictatorship" – is a major political setback for the ruling "PRI" (Institutional Revolutionary Party) regime, which has controlled the country continuously since 1929. The initial damage to Mexico's international image was heightened by the Salinas government's heavy-handed response to the insurrection, which deployed one-fifth of the Mexican army (15,000 troops were brought in) and used aerial bombardment. Mexican and international human rights organizations alleged that "excessive force" had resulted in grave violations of the human rights of the rural population. In retaking the towns, several hundred people were reported killed, mostly guerrillas and some civilians. The former, however, could retreat and likely hold out for a long time in the surrounding mountainous jungle terrain. Chiapas, which borders on Guatemala (see map), is the seventh largest of Mexico's 31 states in size, and the eighth largest in population (though that is still less than 4% of a national total of over 90 million). On most indicators of social and economic welfare, however, the state ranks last. For example, in one of the towns occupied, Ocosingo, illiteracy stands at over 45%. While in recent years the state received more assistance than any other under the Salinas administration's "National Solidarity" program (dubbed "Pronasol"), such expenditures have not addressed the longstanding grievances of the Indian majority against the oligarchical landowning and PRI-connected power structure. The latters's agricultural "modernization" plans, accelerated by the NAFTA, have, moreover, reinforced peasants' fears about the loss of their traditional lands and means of livelihood.

THE AFTERMATH AND CHALLENGE TO THE MEXICAN STATE The Chiapas uprising cannot be understood as just a remote localized tremor. Rather, it is evidence of an earthquake that continues to reverberate across Mexican society and a badly shaken political system.(1) Indeed some in Mexico have called it the world's first "post-Communist revolution". Despite the regime's well-publicized efforts at promoting human rights and political reforms, especially during the sensitive NAFTA negotiations, Mexico's political system has remained highly authoritarian and paternalistic. President Salinas himself is widely suspected of having benefited from systematic fraud to eke out an electoral victory in the 1988 elections, and stands accused of continuing to operate in an autocratic and manipulative manner. In November 1993, the traditional rituals of el destape (the unveiling) and el dedazo (the pointing of the finger) were again orchestrated by the PRI establishment as Salinas personally anointed his chosen successor, 43-year-old Luis Donaldo Colosio – a Salinas protégé who had run the President's 1988 campaign and whom he made PRI president and Secretary of Social Development in charge of Pronasol as well as environmental issues. Colosio thereby became the unchallenged PRI candidate for the next six-year presidential term ("sexenio"), which would normally guarantee his election. Matters could turn out differently, however. The PRI monopoly of state-bureaucratic power can now expect re-invigorated challenges from both the National Action Party (PAN) on the right and the Revolutionary Democratic Party (PRD) on the left, as well as from a growing number of non-governmental and popular organizations within civil society. While giving Salinas high marks for pushing through pro-market economic reforms, observers had acknowledged the lack of credible political reforms to be a growing problem. For example, in a mostly glowing "Survey of Mexico" a year ago, The Economist saw the country being hailed by "the club of rich nations ... as the perfect student of economics," but went on to state bluntly that "Mexico is in no sense a democracy. Government is conducted by an unelected bureaucratic elite accountable only to the president."(2) In the short term, the events in Chiapas could jeopardize Mexico's campaign for membership in the "club" of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), to which Canada belongs. Since joining the GATT in 1986, Mexico's aggressive path of economic liberalization has had considerable international success, culminating in U.S. passage of the NAFTA in late 1993. Within Mexico itself, however, the relationship of market-oriented reforms driven from the top down (termed "Salinastroika") to an overdue political liberalization has been vexed and tenuous at best. If political change seemed in some sense to be inevitable, would it come in time to avoid upsetting the neo-liberal "modernization" project? Many were sceptical even before long-suffering Chiapas exploded into the headlines.(3) The Chiapas warning has so far produced several significant and even ironic developments on the political front. One is the extraordinary role played by the Catholic church, and specifically Bishop Samuel Ruiz of San Cristobal de las Casas, in facilitating talks between the government and the rebels. Although 90% of Mexicans are nominally Catholic, the anti-clerical provisions of the revolutionary-era 1917 constitution were not dropped until 1992. As well, church workers who defended Indian and peasant rights, and organizations such as the respected Fray Bartolome de las Casas Human Rights Centre, have been subject to frequent harassment and vilification, and were previously criticized by conservative clerics. Now Ruiz, who is trusted by the Zapatistas, is a key mediating figure in trying to achieve a peaceful solution. His cathedral was chosen as the site for talks which began 21 February. For its part, the government moved within weeks to control further damage by offering an amnesty to guerrillas who surrendered their arms, and by appointing as its peace envoy Manuel Camacho Solis, who is a son-in-law of a former Chiapas governor and former director of the now defunct Mexican environmental agency SEDUE. Camacho Solis is a Salinas favourite who was Mexico's foreign minister and had also been Mexico City's appointed mayor. Significantly bypassed was the man Salinas had named as his Secretary of Government in January 1993, former Chiapas governor Patrocinio Gonzalez Garrido, whose term had been marred by accusations of corruption and repression. Perhaps more significantly, Camacho Solis had also been Colosio's chief rival for the PRI succession. While Colosio is on the campaign trail making speeches promising "the democratic transformation of our country," it is Camacho Solis who is grabbing most of the spotlight as peace talks get underway with the rebels. How successful the government's efforts will be is another matter. A recent poll in the Mexico City newspaper El Financiero reported that over 70% of those surveyed doubted the honesty of the presidential elections scheduled for this summer.(4) As well, in early February hundreds of unarmed peasants occupied municipal buildings in several Chiapas towns, demanding the removal of local PRI officials. The government has tried to keep the situation under control, observing a ceasefire since 17 January and releasing a number of those detained by the army and police. Crisis management has also produced some further political concessions. When the Chiapas state legislature met to respond to the state of emergency, it voted to replace Governor Elmar Setzer. And in Mexico City in late January, the government signed an agreement with the leaders of nine political parties calling for basic electoral reforms. Nonetheless, promises and peace talks may not be enough, given the fundamental challenge to the status quo. As a perceptive early report in The Economist concluded:

The role of North American free trade in helping to spark the Chiapas revolt relates to the controversy surrounding its proposed "model of development" as much as to any specific provisions of the treaty.(6) By the late 1980s President Salinas had become convinced that entry into such a regional bloc was necessary to Mexico's ambitions to rise to "first world" status. Mexico therefore pushed hard for the negotiations and for a successful result in Washington. Of course, there was a price. Under Bush, the United States brought to the table many demands of its own. Under Clinton the agenda was further enlarged. Apart from the "side" agreements on environmental and labour cooperation, which were reached late in the process and are not part of the actual treaty, the primary U.S. objectives have been economic and strategic. As explained by leading American trade analyst Peter Morici:

While such aims are consistent with the Salinas administration's own modernization and liberalization plans, they have provoked opposition on the grounds that they represent an unacceptable intrusion into national sovereignty and a foreclosure of democratic alternatives. This is especially so, it is argued, for areas – notably energy and land ownership – previously considered sacrosanct under Mexico's leftish 1917 constitution. In part to prepare the way for NAFTA, which is to establish eventual free trade in agricultural products, including the staples corn and beans, the Salinas government introduced a package of constitutional reforms in November 1991. As a result, amendments formally adopted in March 1992 effectively privatized the ejido system of land distribution – adapted from the Indian tradition of communal farming – which had been entrenched to protect peasants' rights following the 1910-17 Revolution. The case for freeing up land sales was that commercial "modernization" of agriculture was necessary if Mexican producers were to compete with cheap food imports, especially of U.S. corn, entering under liberalized trade rules. That scenario, however, only exacerbated fears that hundreds of thousands of "inefficient" subsistence farmers would thereby become "surplus" faster, and be forced off the land to swell the ranks of the poor in already overcrowded and polluted cities. Moreover, it is important to understand that, despite the land reform provisions of the revolutionary constitution, many Indians had never obtained secure land rights. As a recent report observes: "Indian lands, typically held either in the form of ejidos or as communal property, are vulnerable to land grabs by caciques [the term for rural bosses and large landowners] who obtain protection from powerful political figures or agrarian officials."(8) Not without cause has the battle cry of the early hero of the Mexican revolution, Emiliano Zapata – "tierra y libertad" (land and liberty) – resonated through modern Mexican history to the present day. This is both the real and the rhetorical backdrop to the 1994 "Zapatista" army's denunciation of NAFTA as locking in a policy of agricultural commercialization seen as benefiting the land-rich, and not the many Indians in Chiapas who remain landless or who are angered at losing ancestral lands to cattle barons with connections to the ruling PRI. And while NAFTA, combined with infrastructure development, could boost some Chiapas exports (mostly of tropical products and benefiting mainly large growers), in the short term at least, this is overshadowed by a deeper concern that economic adjustment will worsen the already wide income disparities that persist among Mexicans, and that separate the "dynamic" north (where most of the maquila industries are located) from the traditionally poorer and "backward" south. Mexicans who have yet to benefit from the government's program of economic liberalization have reason to be suspicious of its promises. Great wealth has been created at the top, but Mexico still has one of the most unequal income distributions of any country in the world. Perhaps the only surprise is that there has been no social explosion earlier. Between 1982, the year that Mexico's near default triggered the debt crisis, and 1988, the year that Salinas assumed power, real wages dropped by almost half. (The magnitude of this decline was considerably greater than that experienced by the U.S. or Canada during the Great Depression.) Although the Salinas years have brought an uneven economic recovery, the appearance of relative stability has proved to be misleading. It must also be said that since 1988 serious human rights violations have continued. These have been extensively documented by organizations such as Amnesty International, and include the murder or "disappearance" of journalists and opposition political activists. Mexico has also seen rising numbers of poor and unemployed or marginal workers, a development attributed to both the mixed effects of economic restructuring and a population growth that continues to outstrip the potential for new job creation. Now, once again in Mexican history, another violent reaction to delayed social and political reforms threatens economic "progress" and the stability of the ruling regime. The next steps in responding to the crisis will therefore be critical for both the government and the Mexican people. While NAFTA by itself cannot be blamed as the cause of an upheaval that has deep historical roots, as a contributing factor it has become part of the problem. It remains to be determined whether NAFTA can also become part of a solution by bringing about reforms within the Mexican state and society and raising living standards for the indigenous majority in Chiapas and other disadvantaged regions.

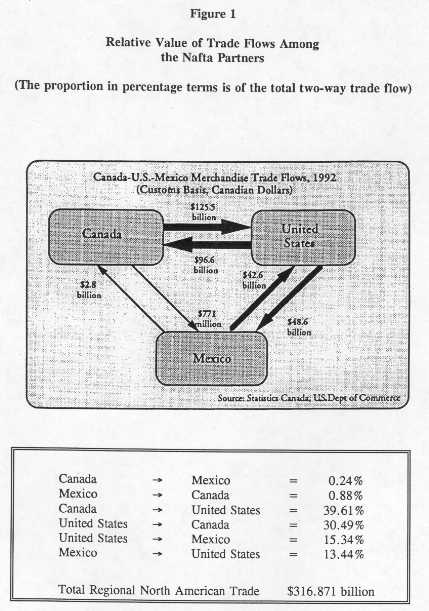

LINKS TO HUMAN RIGHTS – IMPLICATIONS FOR CANADA Canada and Mexico have traditionally enjoyed a good but limited relationship. While the NAFTA is expected to spur increased trade and investment flows, and to deepen exchanges in other areas, this is from a rather low base of activity (see Figure 1). The NAFTA negotiations, which Canada joined mainly for defensive reasons, have intensified the diplomatic relationship between the two countries, as reflected in annual bilateral ministerial-level meetings, which this year are being held 28 February and 1 March in Mexico City. As well, coinciding with the opening of a major Canadian trade exhibition, Prime Minister Chrétien is scheduled to meet with President Salinas during an official visit to Mexico City on 23 and 24 March. The violence in Chiapas has therefore presented the Canadian government with the problem of determining an appropriate response in the very first days of a new era of trilateral partnership. Quite obviously, all three parties to the NAFTA would have preferred a more auspicious backdrop to the beginning of the intergovernmental cooperation required for implementing the treaty and its parallel accords. Much of the controversy within and outside government in Canada revolves around the question of the place of human rights considerations in overall foreign policy, particularly as regards foreign commercial policy, and specifically in this case. In recent years official Canadian policy has evolved towards making a strong linkage in principle between foreign aid and respect for human rights by recipient governments. Addressing the Commonwealth heads of government in 1991, Prime Minister Mulroney boldly stated the Canadian position that "nothing in international relations is more important than respect for individual freedoms and human rights. ...Canada will not subsidize repression and the stifling of democracy."(9)

Source: External Affairs and International Trade Canada, NAFTA – What's It All About?, Ottawa, 1993, p. 3. However, despite being pressed by opposition parties and human rights advocates, the Mulroney government subsequently maintained that such a normative framework was not intended to apply, at least not in the same way, if at all, to trading relationships, where more usual pragmatic and business considerations would still be paramount. Even focusing only on aid flows, research by an officer of the Department of Foreign Affairs itself confirms a long- observed pattern of inconsistent application of human rights policies in cases where significant Canadian commercial interests are at stake.(10) Specifically, throughout the NAFTA negotiations, the Canadian government's stance was that any alleged human rights failings on the part of the Mexican authorities ought not to impede progress towards an economic agreement; all three government parties claimed such an agreement would bring about long-term material improvements for the Mexican people. Essentially the official Canadian position asserted that Mexico's market liberalization and opening to North American influence through NAFTA would act as a positive developmental force that would also favour democratic change and increased respect for human rights.(11) Canada was initially cool to the idea of any side accords addressing social concerns, but accepted the compromises worked out on labour and on environmental cooperation. The latest NAFTA Manual, produced by the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in December 1993, devotes several pages to the North American Agreement on Labour Co-operation, which covers issues with a direct bearing on human rights.(12) This reference document, however, makes no explicit references to human rights or democratic objectives. Since the Chiapas uprising, Foreign Affairs Minister André Ouellet and Secretary of State for Latin America and Africa, Christine Stewart, have expressed Canada's concern over reports of serious human rights violations. At the same time, Trade Minister Roy MacLaren has joined his counterparts in the United States and Mexico in insisting that the events in Chiapas, although regrettable, are an "internal Mexican matter" unrelated to the NAFTA process. At a news conference in Mexico City in mid-January, following the inaugural meeting of the North American Commission, Mr. MacLaren did add that the three governments nonetheless had a responsibility to see that "the benefits of free trade flow through to all segments of society."(13) A few days after, Mrs. Stewart expressed the hope that: "There doesn't have to be a contradiction between human rights and economic expansion."(14) Although in recent years Canadian parliamentarians have recommended stronger linkages between foreign policy decisions and human rights values, the major battleground over Mexico's record on human rights has been in the United States, where the politics of the NAFTA have also been contested most hotly. Paradoxically, while the U.S. lags behind its NAFTA partners in signing on to major international human rights instruments,(15) it has the only legislated framework for attaching human rights conditions to trading relations. For example, Sections 502 and 301, respectively, of the Trade Act of 1974 empower the president to grant preferential duties, or to apply sanctions, contingent on a finding of compliance with, or violation of, fundamental worker rights. Internationally recognized "fair labour standards" – including the right to organize and bargain collectively – have also been used as a benchmark of conduct in the U.S. State Department's annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.(16) Coincidentally, the latest of these reports, delivered to Congress on 31 January 1994, which covers the period well before Chiapas, comes down more harshly than before on Mexico (and also China), reflecting increased attention given to human rights by the Clinton administration. Past reports have often been criticized for going easy on "friendly" countries with which the U.S. has important business or strategic interests. Doubts remain, however, about the weight attached to these findings in overall foreign policy formulation. The State Department's senior policy advisor for human rights and humanitarian affairs is quoted as saying: "The tough question of economic justice versus human rights has not been resolved."(17) Human rights groups in the U.S. have also been unsuccessful in getting Washington to put pressure on Mexico by reviewing that country's status under the worker rights provisions of U.S. preferential trade law pertaining to the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).(18) Prior to the Zapatista insurgency, much had been written about the state of human rights and human rights reform in Mexico. While Mexican governments have traditionally objected to external "interference" in the affairs of sovereign nations, they have also supported human rights in international forums. As well, Mexico's growing international engagements have made the Salinas government more conscious of the country's public image abroad. Clearly the costly push to get NAFTA passed by a sceptical U.S. Congress helped to bring about some gains in the human rights area. This joined growing pressures from within Mexican civil society for legal redress and political accountability. The number of independent human rights NGOs in Mexico has grown rapidly from a handful when Salinas took office in 1988 to several hundred today.(19) In 1990 the government moved to create a National Human Rights Commission, which now boasts more than 600 staff members. Unfortunately, the Mexican Commission has no mandate to investigate political and labour rights violations, and in any event lacks enforcement powers. In general, despite an impressive normative framework, new bureaucratic human rights machinery, and the growth in non-governmental human rights activism, international human rights monitoring groups have still found Mexico's record of adherence to its international obligations to be gravely wanting. Shortly before the NAFTA vote in the U.S. House of Representatives, Americas Watch wrote a cautionary letter to President Clinton:

A supporting Briefing Paper documented how Mexico's labour laws, while strong on paper, in fact afford little protection to most Mexican workers. It contends, moreover, that an entrenched paternalistic system of labour relations, prone to corruption and co-option by the ruling party, "perpetuates itself because Mexico's government and the PRI refuse to be subjected to democratic accountability and because they deem a compliant work force essential to their goals of attracting foreign investment and implementing free trade."(21) Other observers have acknowledged that the "PRI's long-standing corporatist links with labour and the private sector were crucial elements in the president's [Salinas] ability to secure agreement and compliance" with the economic adjustment measures that smoothed the way for the NAFTA negotiations. An important element was the PRI-controlled antipoverty "Solidarity" program that has dispensed more than $11 billion in the past four years.(22) As noted earlier, Chiapas received more funds through this program than any other Mexican state. Yet the January uprising underscored that such compensatory schemes delivered through the old-style patronage networks are no longer enough to forestall popular demands for far-reaching political and social reforms. The question also looms, therefore, whether the main economic development model – predicated as it is on economic integration agreements like the NAFTA, which have largely tried to steer clear of such wider concerns – will still be able to maintain a contained approach to NAFTA implementation that focuses on realizing the agreement's commercial potential, while not adequately addressing the social and political impacts of adjustment. As two Canadian analysts argue:

In the wake of the violence of January 1994, Canadian human rights organizations have been among those sending fact-finding delegations to Chiapas and making appeals to the NAFTA governments to incorporate human rights issues into the management, both bilaterally and trilaterally, of the new North American relationship with Mexico. In an intervention during the annual human rights consultations with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Ed Broadbent, president of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, argued that a number of provisions in international human rights treaties that are binding on both Canada and Mexico pertain directly to the current situation. In making this point he observed that "indigenous peoples, whose right to self-determination is involved, are excluded from the processes intended to deal with the implementation and impact of NAFTA. Furthermore, their protests about the economic transformation underway have been met with harassment and repression, and even torture and disappearances."(24) Ovide Mercredi, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, headed a mission sponsored by the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development to investigate human rights violations in Chiapas. Upon its return to Canada on 20 January, the delegation released a toughly worded statement of findings which also made a number of recommendations to the governments of Mexico and Canada. At a press conference, Mercredi insisted on "an inseparable link between human rights and trade" and asked: "Do we respect human rights, or are we selective about respecting human rights in some countries?"(25) The group's report, which was presented to the Canadian government, revived an earlier proposal developed by the Centre for the creation of a "trilateral, independent human rights monitoring agency that would be mandated to observe, receive complaints, investigate and report annually to the three legislatures on the human rights performance of all three countries, particularly in the context of the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement."(26) (In the U.S., Americas Watch, in its October 1993 letter to President Clinton, had called for an early meeting of NAFTA heads of government on human rights issues, and had urged that the three governments ratify the American Convention on Human Rights and agree to be bound by decisions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the judicial body of the Organization of American States.) An interchurch delegation that had returned from Chiapas a few days earlier also called for a strong Canadian response. It recommended the establishment of an all-party parliamentary fact-finding "mission to Mexico, in consultation with Mexican and Canadian civil and human rights organizations and the Mexican government, in order to investigate the current situation in Chiapas and make recommendations to the Canadian government with respect to its human rights policy [in] trade relations with Mexico."(27) Other international investigations, such as that by an Amnesty International delegation, and subsequently by the International Commission of Jurists and Human Rights Watch, as well as those conducted by Mexican human rights NGOs and Mexico's own National Commission, generally confirm the gravity of the human rights violations in Chiapas attributed to the Mexican security forces. With the start of peace negotiations between the rebels and the Mexican authorities in late February 1994, and some indications of early progress, the country may be entering a new phase in its political development; the outcome of which is uncertain, however. The question before Mexico's North American partners is whether they can support positive change towards greater democracy and respect for human rights, and if so, how. The Salinas government has been understandably sensitive to the damage that the Chiapas uprising could do to its reputation and to Mexico's international standing and it has not welcomed any attention it deems to be unfriendly. For example, Mexican Deputy Foreign Secretary Andres Rozental reacted sharply to early February congressional hearings by the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Western Hemisphere Subcommittee chaired by NAFTA opponent Democrat Robert Torricelli. Rozental warned that: "the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement does not give anyone outside Mexico the right to sit in judgment on matters that Mexicans are solely responsible for resolving." The next few months leading up to the August presidential elections in Mexico will test both the seriousness of Canada's policy on human rights in such controversial contexts, and the capacity of the Mexican government to meet deep internal challenges to its legitimacy in the glare of intense external scrutiny. Perhaps most importantly, this period may determine whether the Mexican people can emerge better off after both the painful economic adjustments of recent years, and the shock to the political system delivered by the Zapatistas since January 1994. (1) See the article by prominent government critic Jorge Castaneda, "The Other Mexico Reveals Itself," The Ottawa Citizen, 7 January, 1994, p. A9. (2) "Survey of Mexico," The Economist, 13 February, 1993, p. 1-2. (3) See Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, "Reaching Democracy from Chiapas," El Financiero, 2 March 1992; Michael Coppedge, "Mexican Democracy: You Can't Get There from Here," in Riordan Roett, ed., Political and Economic Liberalization in Mexico: At A Critical Juncture?, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder & London, 1993. (4) Cited in Marci McDonald, "Mexico's Wake-Up Call," Maclean's, 7 February 1994, p. 37. (5) "Mexico's Second-Class Citizens Say Enough Is Enough," The Economist, 8 January 1994, p. 42. (6) Numerous articles and books explore aspects of this debate. See especially: Richard Belous and Jonathan Lemco, eds., NAFTA as a Model of Development: The Benefits and Costs of Merging High and Low Wage Areas, National Planning Association Report #266, Washington, D.C., 1993. (7) Peter Morici, "Grasping the Benefits of NAFTA," Current History, special issue on Mexico, Vol. 92, No. 571, February 1993, p. 50, 54. (8) "Mexico," Americas Watch, New York and Washington D.C., Vol. V, No. 10, October 1993, p. 12. (9) Cited in Gerald Schmitz, "Human Rights, Democratization, and International Conflict," in Fen Hampson and Christopher Maule, eds., Canada Among Nations 1992-93: A New World Order?, Carleton University Press, Ottawa, 1992, p. 242. (10) See Leslie Norton, "L'incidence de la violation flagrante et sytématique des droits de la personne sur les relations bilatérales du Canada," Études internationales, Vol. XXIV, No. 4, December 1993, p. 787-811. (11) This is based perhaps more on faith than evidence. Recent scholarship is sceptical of assumptions that economic liberalization will assist sustainable democratic transitions. See, for example, "Economic Liberalization and Democratization: Explorations of the Linkages," special issue of World Development, Vol. 21, No. 8, August 1993. (12) For a succinct critical assessment of its provisions see Ann Weston, "The NAFTA Labour Side-Agreement: Soft Bark and Not Much Bite?," Review: A Newsletter of the North-South Institute, Winter 1994, p. 7-8. (13) "Canadian Investment in Mexico Expected To Rise Despite Conflict, Says Trade Minister," The Ottawa Citizen, 15 January 1994, p. A9. (14) Cited by Ed Broadbent, President of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development in his "Intervention on Mexico" during the consultations in preparation for the 50th session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, Ottawa, 19 January 1994. (15) Mexico might even be said to be a leader in the area of ratification – including acceptance of 73 of 171 International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions – though obviously such ratification has not produced a lead in either enforcement or practice. The U.S. has only just ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Canada did so in 1976), and is alone among the three in not having ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. (16) Thomas Gibbons, "Tough Trade-Offs," Human Rights, Vol. 19, No. 2, Spring 1992, p. 26-30. (17) Ben Barber, "Human Rights Report Sets Global Standard," The Christian Science Monitor, 26 January, p. 8. (18) See International Labor Rights Education and Research Fund, "Labor Rights in Mexico," Petition and Request for Review to the U.S. Trade Representative, 1 June 1993, reprinted in "Organizing Workers in Mexico, A NAFTA Issue," Hearing before the Employment, Housing, and Aviation Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives, 15 July 1993, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. (19) Ellen Lutz, "Human Rights in Mexico: Cause for Continuing Concern," Current History, February 1993, p. 78ff. (20) "Mexico: Human Rights Watch/Americas Watch Writes to President Clinton Urging NAFTA Summit on Human Rights," Washington D.C., 26 October 1993, News From America Watch, October 1993, p. 2-3. (21) "Mexico," Americas Watch, October 1993, p. 10. (22) Stephan Haggard and Steven Webb, "What Do We Know about the Political Economy of Economic Policy Reform?" referring to the study by Kaufman, Bazdresch and Heredia on "The Mexican Solidarity Pact of 1989" (The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 8, No. 2, July 1993, p. 150.) (23) Roy Culpeper and Ann Weston, "Responding to Chiapas: Canada at the Crossroads," The Winnipeg Free Press, 13 January 1994, p. A7. (24) "Intervention on Mexico," 19 January 1994. (25) "Link Rights to Trade, Mercredi urges," Toronto Star, 22 January 1994. (26) "Mission to a Forgotten People," Preliminary Report, International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, Montreal, January 1994, p. 6. (27) See "Press Communique: Canadian Delegation to Chiapas," Mexico City, 15 January 1994, and "Recommendations" presented to the Departmental human rights consultations, Ottawa, 19 January 1994.

|