|

BP-370E

GENDER-RELATED REFUGEE CLAIMS

Prepared by Margaret Young TABLE

OF CONTENTS APPROACHES TO PERSECUTION BASED ON GENDER A. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 3. For Reasons of Political Opinion C. Immigration and Refugee Board Guidelines DOMESTIC VIOLENCE -- A SPECIAL CASE? ADDING GENDER TO THE REFUGEE DEFINITION

GENDER-RELATED REFUGEE CLAIMS

In 1991, a two-member panel of the Immigration and Refugee Board handed down a decision in a refugee case that provoked a storm of controversy lasting for over a year. Although that particular case was satisfactorily settled in January 1993 (when the woman was given permission to stay in Canada), the general issues it raised continue to be debated. This paper will outline and discuss that case and will then summarize developments in those aspects of refugee law that deal with gender-related claims. Nada (not her real name) claimed refugee status in Canada in April 1991 on the basis of persecution in her homeland, Saudi Arabia. She based her claim to being persecuted on the grounds of religion, political opinion and membership in a particular social group. The Refugee Division panel rejected her claim in a brief decision dated 24 September 1991.(1) In her testimony, Nada had described herself as a revolutionary, unwilling to wear her veil in public except to work or in order to not cause grief to her father. As a result of her non-conformism, she testified that men had subjected her to indecent words and gestures. She also described the actions of the private "guardians" of public morality, the Mutawwi'in, the Committee for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. The panel found that the government of Saudi Arabia did not tolerate any abuses by the Mutawwi'in, and concluded that Nada had not proved that she had been a victim, or had risked being a victim, of this organization. In effect, the panel appeared to find that the grounds for persecution had not been made out. The panel then went on to make the comments that became particularly controversial:

In this paragraph the panel seemed to be saying that laws that discriminate against women generally are unobjectionable, that women should act so as to please their family and that, in particular, they should submit to their fathers. It was these sentiments, as well as the negative decision itself, that fed the subsequent controversy. Subsequent to the rejection by the Refugee Division, Nada's application to the Federal Court to permit an appeal was turned down, and departmental officials found that there were no humanitarian and compassionate grounds on which to let her stay. Nada turned to the media. Human rights advocates and women's groups responded quickly to the decision, urging the Minister to broaden the definition of refugee to cover claims based on gender. Mr. Ed Broadbent, head of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, was one prominent voice: "If we believe as a society that women's rights are human rights, then it is time to stop discriminating against women in refugee policy."(2) The media -- print, radio and television -- all covered the question extensively. Even after the government softened its position, certain groups, in particular the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, urged a general moratorium on deportations from Canada of women whose refugee claims had been rejected and who claimed to fear abuse in their native countries.(3) The Minister of Employment and Immigration's evolving response to the controversy over Nada's case became a story in itself. In the middle of January 1993, Mr. Valcourt stated: "I don't think Canada should unilaterally try to impose its values on the rest of the world. Canada cannot go it alone, we just cannot."(4) And on the same occasion: "The laws of general application in countries of the world are not necessarily laws that we in this country would want to promote because of our values but will Canada act as an imperialist country and impose its values on other countries around the world?"(5) In response to pressure to widen the refugee definition to include gender as a basis for a refugee claim, Mr. Valcourt made it clear that Canada would not be leading any campaign in the international community; he cited the fear of opening the floodgates to women fleeing abuse at a time when Canada is trying to control the flow of refugees. He pointed out that women facing persecution could come within that part of the refugee definition relating to a "particular social group," or could be allowed to stay on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.(6) In the face of a storm of protests and publicity, the government appeared to soften its position on broadening the definition of refugee. An aide to the Minister was reported to have stated that Canada would consider raising the matter with the United Nations, but only if there was widespread support: "If there was a consensus on this gender issue in this country, and it was brought back to the government, the government could consider making representations on this issue to the United Nations."(7) Only days later, on 29 January 1993, Minister Valcourt announced that Nada would be allowed to stay in this country and that Canada would consider refugee status for women claiming to have been persecuted because of their sex. He announced that the Immigration and Refugee Board would soon be issuing guidelines on how to deal with such cases. The guidelines would be "intended to encourage and promote consistency and coherence in the treatment of refugee claims in Canada," stated the Minister.(8) APPROACHES TO PERSECUTION BASED ON GENDER As the controversy raged over Nada's individual case and the broader issues it raised, it became clear that these issues were not as black and white as had at first appeared. Experts pointed out that a woman could already succeed in a refugee claim related to her gender, even in the absence of an explicit reference to gender in the refugee definition. This section of the paper discusses the degree of protection that may currently be afforded to women. The Immigration Act defines refugee, in part, as follows:

A. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) The UNHCR Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status does not specifically mention gender-related claims or refugee claims by women in its discussion of the meaning and application of the refugee definition. In 1985, however, the UNHCR's Executive Committee adopted a Conclusion entitled "Refugee Women and International Protection."(10) The Conclusion noted the special problems experienced by refugee women and girls, who constitute the majority of the world's refugees. In addition to recommendations related to international protection, the Conclusion also dealt with national refugee determination systems. The Executive Committee:

Note that the term "social mores" is quite broad and could include breach of strict rules that applied only to women. (Of course, for the definition to apply, persecution for violation of the rules would also have to be made out.) Although not binding on individual states, this recommendation reflected the evolving view that these kinds of claims could be received and assessed by individual countries applying the Convention standard. In subsequent years, the particular needs of refugee women in general continued to be addressed and the recommendations of the Executive Committee in connection with the recognition of gender-related claims became broader and stronger. Instead of states being "free to adopt" the position that women could be considered a "particular social group" (as the 1985 guidelines had stated), guidelines adopted in 1991 stressed that women:

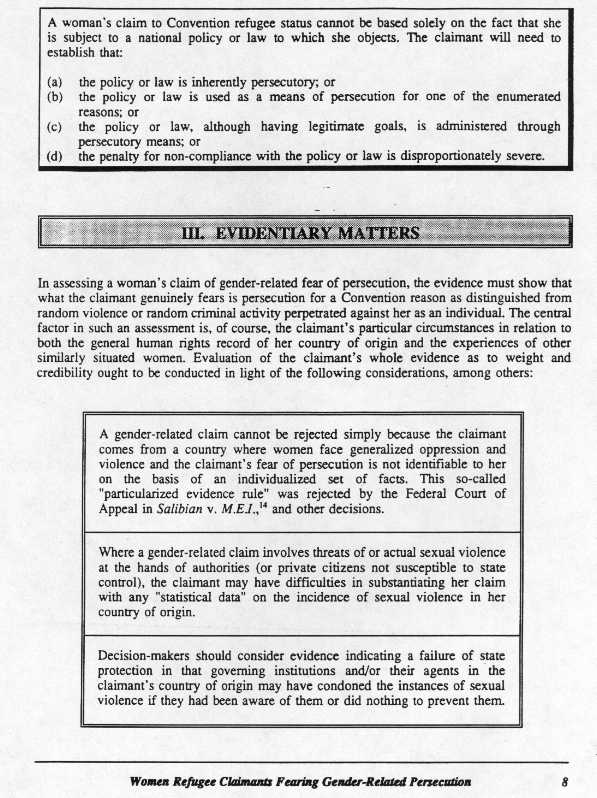

In assessing claims to refugee status, the structure of the refugee definition requires that a number of factors be taken into account.(13) A claimant must have a well-founded fear that he or she will be persecuted if returned home and persecution must be connected to or arise from one of the named characteristics relating to the individual's civil or political status: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion. The following provides a very brief summary of these various elements as they apply to gender-related claims. It should be noted that, while persecution and at least one of the named groups are central elements to a claim, many refugee claims present more than one ground (as was argued in the Nada case). Persecution is not discrimination or inconvenience. Nor is it a transient or isolated harm. Rather, it is a serious and sustained harm in which the individual's country is itself engaging or which it is unable or unwilling to prevent. Gender-related claims must meet this test in the same manner as all other claims. Whether a harm is sufficiently serious to constitute persecution may be assessed by reference to basic human rights as set out in core international documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Not all the rights enunciated in those documents would, if breached, necessarily amount to persecution, but many would, including (to name only a few): freedom from arbitrary deprivation of life; freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman treatment or punishment; protection against slavery; the right to legal recognition as a person; freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention; the right to a fair trial; the right to personal integrity; the right to freedom of movement; the right to leave and return to one's country and the right to vote. Violation of a wide range of social and economic rights may also constitute persecution in certain circumstances. Thus, women who face persistent harassment or violation of fundamental rights that the state condones or fails to prevent, would meet this aspect of the refugee definition. It is important to note that physical assault and rape may constitute persecution. Certain countries place significant restrictions upon women. Where these restrictions arise from the official religion of the country, disobeying the rules may be seen as anti-religious and punishable on that account. The Convention, however, protects both the right to hold a religious belief and the right not to hold a religious belief.(14) Thus, those who transgress the social mores of their society may, in some cases, claim to be persecuted on the basis of religion. 3. For Reasons of Political Opinion In cases similar to those just described, in which the laws of the state are those of the official religion, rejecting "cultural/religious norms" that discriminate against women may be seen as a political act. Thus, actions that are not normally seen as "political" in the West, such as dressing in an unapproved manner, make a statement that authorities interpret as defiantly political as challenging the fundamental tenets of the state and its power to control its citizens.(15) Whether challenging prevailing norms is classified in terms of religion, or in terms of political opinion, if measures taken to enforce the prevailing norms amount to persecution, or if the prevailing norms themselves violate core international human rights standards, there will be a basis for a refugee claim. There is no one agreed-upon view of the definition or scope of "particular social group." As noted above, the Executive Committee of the UNHCR has recognized that women who have transgressed the social mores of their country may be considered such a group. Hathaway identifies gender-based groups as a "clear example" of a particular social group because their members share a common and immutable characteristic -- their sex.(16) This view was accepted in Canada in the case of Zekiye Incirciyan,(17) a Turkish widow who was persecuted in her country because she did not live under the protection of a male relative. The particular social group was identified as "single women living in a Moslem country without the protection of a male relative."(18) The approach of that case has been accepted in other Immigration and Refugee Board decisions in relation to women in Lebanon and Sri Lanka,(19) and, interestingly in view of the Nada case, Iran.(20) In April 1993, the Federal Court of Appeal held that women in China with more than one child who are faced with forced sterilization form a particular social group.(21) The Court stated: "All of the people coming within this group are united or identified by a purpose which is so fundamental to their human dignity that they should not be required to alter it on the basis that interference with a woman's reproductive liberty is a basic right 'rank[ing] high in our scale of values.'"(22) Only a few months later, however, a panel of the Federal Court of Appeal held that parents in China with more than one child were not a particular social group.(23) In June 1993, the Supreme Court of Canada in Ward(24) set out the framework for assessing "particular social groups" for the purpose of the Convention. The Court delineated three possibilities:

The Court explicitly recognized that claims based on gender would fall into the first category, thus confirming the trend of the Executive Committee of the UNHCR, the opinion of Hathaway and the previous Canadian decisions cited.(26) Women refugee claimants may also be able to assert refugee claims based on their race or their nationality in situations where laws impact on women solely as women. For example, a woman of one race living in a country where the majority is of a different racial origin may be persecuted both because of her origins and her gender. C. Immigration and Refugee Board Guidelines As may be seen from the above discussion, the framework for acceptance of gender-related claims has been laid in refugee law, and, in practice, the Board has accepted some of these types of claims in the past. As the Nada decision illustrated (by being almost a caricature), however, the necessary conceptual framework for the analysis of such claims was not well-developed in all Board members. Indeed, in addition to an apparent lack of sophistication regarding refugee law, the decision revealed overt sexism (the decision said that Nada, as a daughter, should "show consideration for the feelings of her father") that suggested a wider problem. While the public debate continued, the Chair of the Immigration and Refugee Board was developing Guidelines to assist members in dealing with gender-related claims.(27) Draft Guidelines were circulated for consultation purposes in August 1992, with the final version released on 9 March 1993, in conjunction with International Women's Day; they may be found as an Appendix to this paper. The Guidelines, entitled "Women Refugee Claimants Fearing Gender-Related Persecution," coupled with training initiatives undertaken by the Board, are designed to provide members with the conceptual framework for consideration of gender-related claims and should help to foster sensitivity to some of the unique issues and problems presented by such claims. The IRB Guidelines are not legally binding in any strict sense. Members of the Board are independent decision-makers who decide cases on the basis of the law, the facts as presented to them, similar decisions in the past (although they are not bound by these) and by objective information relating to the countries of origin of the claimants. The Guidelines, however, form a succinct statement of the issues and refer to specific factual situations and relevant cases in the past. Given the care with which the Guidelines were researched, members would need good reasons to deviate from the principles on which they are based. Explicit instructions to that effect have been given to all members of the Board. The concluding section of a memorandum from the Chairperson entitled "Procedures for the Guideline-Making Process - s. 65(3) and (4) of the Immigration Act," provides as follows:

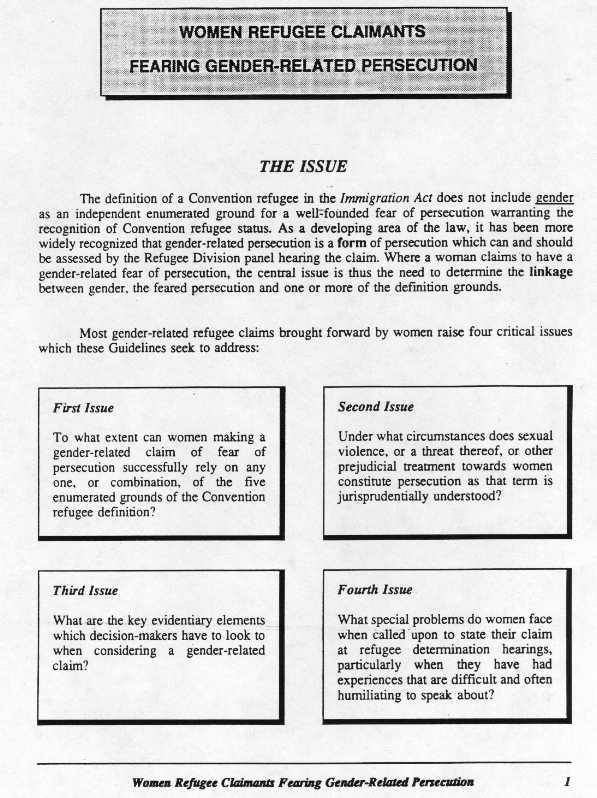

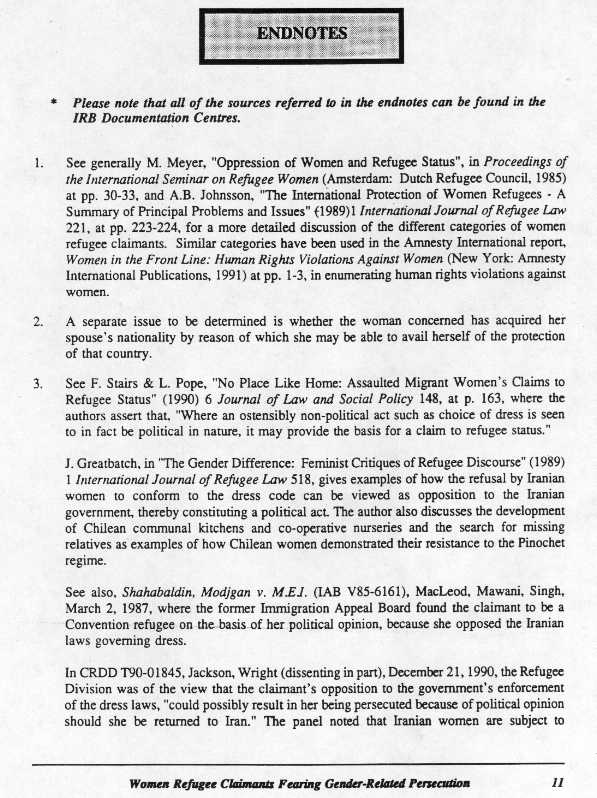

The IRB Guidelines address four critical issues:

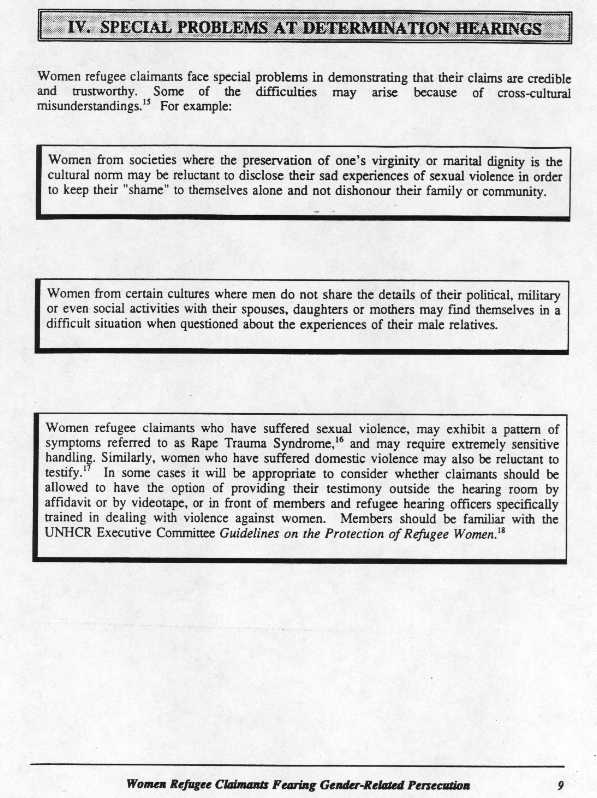

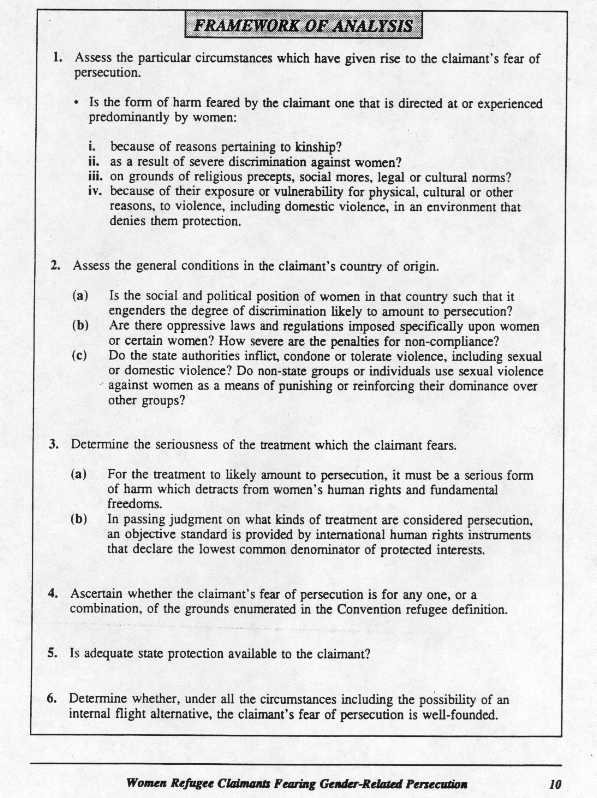

In addition to identifying and addressing the above elements, the Guidelines are also helpful in setting out four broad categories of women refugee claimants. The first category consists of women who fear persecution on the same grounds as men and in similar circumstances. Thus, while the methods of persecuting women may be different from those used to persecute men (women are more likely to be raped, for example), and while women may face different problems in asserting their claims (talking about the rape, for example, may pose great problems for women because of a cultural stigma), the essence of the claim is the same for each gender. Another category consists of women who fear persecution because of the activities of their family members, rather than because of their own status, activities or beliefs. "Persecution of kin" has as its goal the discovery of information relating to the family. In addition, women may be assumed to hold beliefs similar to those of their family members and persecuted on that basis. A persecuted family group may be considered a "particular social group" for the purpose of the refugee definition. The Guidelines describe the third group of women as consisting of those "who fear persecution arising from certain circumstances of severe discrimination on grounds of gender or acts of violence either by public authorities or at the hands of private citizens from whose actions the state is unwilling or unable to adequately protect the concerned persons" (emphasis in original). This category would likely cover such cases as genital mutilation or bride burning. The fourth group of women are those who fear persecution because in their country of origin they have transgressed religious or customary laws and practices that discriminate against women. The Guidelines cite such social traditions or cultural norms as choosing their own husbands instead of accepting an arranged marriage, wearing makeup, having hair showing or wearing a certain type of clothing. Such women may be considered as a gender-defined social group. The Guidelines state that most gender-specific claims to refugee status can be determined on grounds of religion or political opinion, and seem to suggest that "particular social group" should be a "residual category," to be considered only after consideration of more specific grounds. In discussing the ambit of that term the Guidelines note that the possibility that a large number of women could be included in the group is irrelevant, provided that the social group suffers or fears discrimination that is not suffered by the general population or by other women. The Guidelines caution that mere membership in a group is not sufficient -- a claimant must still have a genuine fear of harm sufficient to constitute persecution should she be returned home,(28) her gender must be the reason for the feared harm, and she must have no reasonable expectation that her home country can protect her. The Guidelines also seek to sensitize decision-makers to the special evidentiary and other problems women face in presenting their claims. These include cultural pressures that make it difficult to reveal or discuss persecution of a sexual nature; the lingering psychological trauma of such assaults; the difficulties of proving persecution based on the activities of family members and the problems of characterizing state involvement in societies where women are denied rights generally. Its Chairperson, Nurjehan Mawani, has committed the Board to monitoring the impact of the Guidelines in individual refugee claims and revising them as the law evolves.(29) On the first anniversary of their release, the Board announced that the previous year some 350 gender-related claims had been identified. Of the 170 claims completed, 70% had been decided in favour of the claimant.(30) DOMESTIC VIOLENCE -- A SPECIAL CASE? Women who flee their homelands to escape domestic violence, or who have reason to fear such violence should they be forced to return home, also request Canada's protection.(31) In this, they resemble other refugee claimants who seek Canada's protection against serious harm should they be forced to return to their country of origin. The question is: to what extent can women who fear abusive domestic situations claim Canada's protection through the refugee status determination system? What additional avenues are open to them within the immigration system? The IRB Guidelines allude to this issue but provide less guidance for this matter than for the other aspects of gender-related claims. This is perhaps inevitable because the issue is relatively new. As a group, women refugee claimants in this situation appear to fall within the third broad category described above (p. 12). This category reads in full as follows:

Note that at least one of the enumerated grounds must still be present. Domestic violence, however, is less likely to be related to the grounds of race, religion, nationality, or political opinion. This leaves membership in a particular social group. The question thus becomes: to what extent can victims of domestic violence be said to form a particular social group and thus be brought within the ambit of the Convention? The Guidelines place these women as part of a sub-group which "can be identified by reference to the fact of their exposure or vulnerability for physical, cultural or other reasons, to violence, including domestic violence, in an environment that denies them protection. These women face violence amounting to persecution, because of their particular vulnerability as women in their societies and because they are so unprotected."(33) (emphasis in original) The case law is still embryonic. The IRB Guidelines cite three cases, all decided in late 1992 or early 1993.(34) In one, the Federal Court of Appeal raised the question, without deciding one way or the other, of whether "Trinidadian women subject to wife abuse" could constitute a particular social group.(35) The other cases were decisions of the Refugee Division and they took opposing views. In one, the claimant was found to be a member of a social group described as "unprotected Zimbabwean women or girls subject to wife abuse."(36) In the other, the panel found that abused women unprotected by their country of origin were not a particular social group. The panel reasoned that the existence of persecution alone should not define a particular social group. The Guidelines, however, suggest that abused women can form a particular social group based on the fact of their abuse. The view that a particular social group can be in part defined by its abuse gained support in Cheung, in which the Federal Court of Appeal held that women in China facing coerced sterilization as a result of the country's one-child policy could form a particular social group. Although in Ward the Supreme Court of Canada approved the Cheung decision, it also rejected a broad approach whereby people would become members of a particular social group merely by virtue of their common victimization.(37) Bound to arise is the question of how many claimants could come within the scope of "particular social group," if abused women were to be included. This question is not, however, relevant to refugee law.(38) As the Guidelines (and refugee experts) point out, large numbers of people may also share the other enumerated characteristics of race, religion, nationality and political opinion.(39) Domestic violence, however, seems different in kind, since, unfortunately, it is an attribute of virtually all societies. If "unprotected Zimbabwean women or girls subject to wife abuse" formed a social group, then so would "unprotected African women and girls" and, by extension, all unprotected women and girls subject to abuse. Since no country, including Canada, can guarantee security in the face of a determined abuser, the implications of a policy suggesting that any abused woman could find refuge in Canada would be staggering.(40) Note that the social group of Zimbabwean women was carefully characterized as "unprotected."(41) A lack of state protection is an essential element of a well-founded fear of persecution.(42) One way of limiting the scope of a social group based on abuse would be through the definition of "unprotected." Failure of a state through its laws to prevent abuse would clearly constitute such a lack of protection. Going one step further, if a state's laws did on their face provide protection but, through policy, practice or conditions in the country, were not enforced or enforceable, the lack of protection could be considered sufficient to justify a claimant's seeking the protection of another state. A recent decision of the Federal Court dealt with this issue of protection in the context of admission to Canada on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.(43) The applicant was about to be deported and applied for a stay of execution of the order. One of the grounds argued was that she had been abused by her husband in Dominica and that she would not receive protection in that country. The judge stated that, "while domestic violence and the extent to which victims may receive protection from appropriate authorities in their countries of origin is a serious matter, there must be evidence that an applicant is the victim of abuse and that there is no protection afforded in her country of origin" (emphasis added).(44) In deciding against the applicant, the judge took note of recent efforts by the government of Dominica to raise awareness of the issue of domestic violence and to conduct research into it. He noted that the Welfare Department in that country often provides assistance to victims in the form of temporary shelter. Although acknowledging that the police are often reluctant to interfere in "domestic quarrels," he nevertheless concluded that, on the evidence, he was "not satisfied that Dominica is a country in which domestic violence is condoned or where there is no recourse for victims of domestic violence."(45) The applicant has appealed the decision. The five children under her care in Canada have won the right to have their case -- that they not be deprived of Mrs. Harpers's care -- heard at the same time. The above case was not a refugee determination case. In the refugee context, it is still unclear how far the ambit of "social group" can be stretched in domestic abuse cases. Nor is it clear how rigorous the test will be for determining a lack of state protection and the supporting evidence that would be required. In her 1993 speech at the University of Ottawa, the Chairperson of the Board referred to positive decisions in domestic abuse cases concerning women from Ecuador and Honduras. On the other hand, a Tunisian woman had been rejected because the Board found that her country offered adequate protection. Since then, a Russian woman has been found to be a refugee on the basis of an abusive relationship with an underworld figure with ties to the Russian police deemed sufficient to "put her persecutor above the law."(46) Even if women claiming to fear serious domestic abuse should they be returned home are not easily accommodated within the refugee determination system, this not does mean that compelling cases would not (or should not) receive protection from Canada. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration has a humanitarian and compassionate discretion that may be used in such cases and, indeed, was eventually used in Nada's case, although only in response to public pressure. The advantage of such an approach is that the Convention refugee definition need not be extended to cover situations it was never intended to cover and which it may fit uneasily. On the other hand, the disadvantages of relying on the Minister's humanitarian and compassionate jurisdiction, are significant. Claimants in the refugee determination system receive a hearing, may have counsel to present their case, and may apply to the courts for leave to appeal a negative decision. The assessment of applicants on humanitarian grounds, on the other hand, is an administrative action. Although the decision-maker must be fair, there are few rights available to applicants and no right to be heard in person. Rejected applicants may try to garner support from sympathetic groups or organizations and may take their case to the media, but that is generally their only recourse. ADDING GENDER TO THE REFUGEE DEFINITION So far, the issues raised by gender-related refugee claims have been discussed in relation to the existing definition of Convention refugee in international and Canadian law, specifically the five enumerated grounds to which a claim to persecution must be related. Under the existing framework, gender-related claims are first assessed in relation to persecution on the grounds (in particular) of religion and political opinion, and, if these are not applicable, of membership in a particular social group. As discussed above, this approach is seen in the Immigration and Refugee Board Guidelines, in some past refugee decisions, and in training given to members in the application of the refugee definition. Because gender issues are considered under the existing law, evolution of this law to cover gender-related claims has the advantage of not requiring legislation. Incremental, yet ultimately substantial, changes in attitudes and policies may thus be made within the existing framework without seeming revolutionary. Another approach would be to amend Canadian law to include gender as an additional ground of persecution under which individuals could claim Canada's protection. There would be several advantages to this. The issues in these claims would be confronted directly, rather than indirectly. Rather than claimants having to mould their claims to fit established criteria that may not be entirely appropriate, they could refer directly to persecution on grounds relating to gender. This argument may carry less force following the endorsement of gender claims as falling within a particular social group. It could also be argued that if gender were an enumerated ground of persecution, gender-related claims would be considered more seriously and women's rights as human rights would be advanced in a very tangible way. It would become much more difficult to dismiss women's rights as merely "cultural" issues, or to treat laws that discriminate against women as laws of general application to which women should be required to subscribe, even when those laws violate basic international human rights norms. There are, however, several arguments against including gender as an enumerated ground of persecution in the definition. The first is that it is not necessary. As noted above, the traditional grounds of persecution may be soundly interpreted so as to respond to many gender-related claims. Further, the concept of a social group is proving sufficiently elastic to accommodate other gender-related claims that are not so easily categorized. It could be argued that if the current definition is working (or can be made to work through training and guidelines), we need not tinker with it. Even if such an amendment were made, its ambit would still be unclear. To what extent would it cover cases of domestic violence, for example. Would the amendment help (is it intended to help?) a victim of domestic violence from, for example, the United States, who could prove that, although protective laws, policies and practices are all in place, her husband is nevertheless likely to succeed in tracking her down and murdering her? In short, all the questions likely be raised and decided in due course about the scope of the existing refugee definition with respect to gender-related claims would still have to be raised and decided. Critics of the proposal might also raise the argument that if the refugee definition is opened up to add gender, it should also be amended to assist members of other groups. Homosexuals, for example, have received protection in the past as part of a particular social group.(47) Would they have a valid argument that they too should be protected specifically in the refugee definition? Proponents of the gender amendment would perhaps have to be prepared to explain why women (who would be its primary beneficiary) should be protected more directly than other groups, who would have to be content with being considered part of a particular social group. This discussion has centred on amending Canada's domestic law to add gender to the refugee definition. Of course, this definition mirrors the international definition. Should Canada campaign to have the definition in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees changed as well? The advantages of doing so would be the same as outlined above for the Canadian context, in that such advocacy would raise issues of women's human rights and heighten awareness. Such a change would, however, be unlikely internationally, as states already struggle with what they perceive to be unmanageable flows of refugee claims. The chance of success would be remote for any proposal that could have the effect of increasing the pool of potential claimants. Further, there is also the possibility that, in the current climate, a formal debate on the refugee definition could lead to changes in the opposite direction -- that is, tightening the definition to make it more restrictive. In closing, it should be noted that, even once training has taken place and Refugee Division members have been sensitized to the issues surrounding gender-related claims, not all claims by women citing fear of persecution relating to their gender will be accepted, any more than are all refugee claims by men. Proving a fear of persecution is an onerous burden for any claimant. Women have, however, a right to expect that the refugee definition will be applied to them in a flexible manner that is attuned to issues affecting them particularly because of their gender, and without sexist bias. It also seems reasonable to expect that women who are rejected as refugee claimants but who nevertheless face serious harm if returned to their country of origin should receive sensitive treatment by the government, on a case by case basis. In forcing these issues forward for public discussion and action, Canada should be grateful to "Nada."

(1) Immigration and Refugee Board Decision, File no. M91-04822. (2) Calgary Herald, 23 January 1993. (3) Ottawa Citizen, 3 February 1993. (4) London Free Press, 16 January 1993. (5) The House, CBC Radio, 16 January 1993. (6) Globe and Mail (Toronto), 16 January 1993. (7) Ottawa Citizen, 25 January 1993. (8) Toronto Star, 30 January 1993. The Guidelines had been circulating in draft form for consultative purpose for some months. (9) Immigration Act, RSC 1985, c. I-2, s. 2. The Canadian definition is based on that found in the international Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, to which Canada is a signatory. (10) 1985 (Executive Committee -- 36th Session), No. 39 (XXXVI). Conclusion endorsed by the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme upon the Recommendation of the Sub-Committee of the Whole on International Protection of Refugees. (11) Guidelines on the Protection of Refugee Women, EC/SCP/67 (July 22, 1991), quoted in Women Refugee Claimants Fearing Gender-Related Persecution, Guidelines Issued by the Chairperson Pursuant to Section 65(3) of the Immigration Act, Immigration and Refugee Board 9 March 1993, p. 12 (hereafter, "Guidelines"). (12) This section of the paper draws from James C. Hathaway, The Law of Refugee Status, Butterworths Canada Ltd., 1991 (hereafter "Hathaway"). (13) Several of these will be assumed for present purposes; these are: that the claimant is outside her country of nationality or permanent residence and that there are no reasons relating to criminality or security that would deprive an otherwise qualifying claimant of protection. (14) Ibid., p. 145. (15) Hathaway cites an Immigration Appeal Board decision in 1987 (Mokjgan Shahabaldin, V85-6161) in which an Iranian woman's unwillingness to wear the chador and participate in Islamic functions was interpreted as an expression of political opinion. (16) Hathaway (1991), p. 162. (17) Immigration Appeal Board Decision M87-1541X, 10 August 1987. (18) Quoted by Hathaway, p. 162. (19) Ibid. (20) CRDD T89-06969, T89-06970, T89-06971. In their 1990 decision the panel found that "women and girls who do not conform to Islamic fundamentalist norms," were members of a particular social group. (21) Cheung v. Canada, (Minister of Employment and Immigration), [1993] 2 F.C. 314 (C.A.) (22) Ibid., p. 322. (23) Chan v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration), [1993] F.C. No. 742, Doc. A-233-92 (F.C.A.) Dissenting reasons were given by Mr. Justice Mahoney, who had been on the panel that decided Cheung. (24) Canada (Attorney-General) v. Ward, [1993] 2 S.C.R. 689 (S.C.C.) (25) Ibid., p. 739. (26) Hathaway (1991), p. 162. (27) With amendments to the Immigration Act that came into force on 1 February 1993, Board guidelines were given a statutory basis. Their purpose is "to assist the members of the Refugee Division and Appeal Division in carrying out their duties under this Act" (section 65(3)). In addition, they serve to foster consistency in what is a very decentralized system. Note that the Guidelines apply only to Board members, not to visa officers selecting refugees abroad, although the Guidelines have been supplied to these officers. (28) On page 10 of the Guidelines it is noted that for treatment to amount to persecution, "it must be a serious form of harm which detracts from women's human rights and fundamental freedoms." An objective standard of what constitutes these forms of harm may be found in international human rights instruments. Note that in the case of Cheung (referred to below), the Court referred to Articles 3 and 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in concluding that Chinese women facing forced sterilization were being persecuted. Article 3 states: "Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person." Article 5 states: "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment." (29) Nurjehan Mawani, "The Factual and Legal Legitimacy of Addressing Gender Issues, "Refuge, Vol. 13, No. 4 (July-August 1993), p. 8. (30) News Release, Immigration and Refugee Branch, 9 March 1994. (31) In the former situation a woman could flee an abusive husband in her home country and come to Canada. In the latter situation, an abusive husband of a couple living in Canada could have returned (or been deported) to his homeland. In either case, the wife fears a resumption of the abuse should she be required to return home. (32) Guidelines, p. 3. (33) Ibid., p. 6. (34) Ibid., p. 14. (35) Canada v. Mayers, [1993] 1 F.C. 154 (C.A.). In Mayers, the Court held that the credible basis panel should have decided that such a claim should have been sent for a full hearing, in view of the fact that the law was not settled in this area. (36) CRDD U9-06668, 19 February 1993. It is noteworthy that the panel found her claim to persecution on grounds of religion would have been sufficient. The panel, however, went on to place her in two particular social groups: unprotected Zimbabwean women or girls subject to wife abuse and Zimbabwean women or girls forced to marry according to customary laws. (37) Ward, p. 729. (38) Although irrelevant to refugee law, it would be naive to pretend that the question of numbers (the "floodgates" argument) is not relevant to national governments. (39) Guidelines, p. 6. (40) It must be remembered that the government does place substantial barriers to the arrival of refugee claimants. Chief among these are visa requirements. In addition, women fleeing from one country to another face many economic, physical and social problems not faced to the same degree by men. (41) In this case, the claimant had been forced to enter a polygamous marriage at the age of 15 with a man many years her senior. Because of his wealth and influence, her repeated attempts to invoke police protection from his physical abuse were unsuccessful. Further, the panel concluded that because of the reach of his power and position, it would not be possible for her to seek refuge elsewhere in Zimbabwe. (42) See, for example, Hathaway (1991), p. 105. (43) Harper v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration (1993), 62 F.T.R. 96 (Fed T.D.). (44) Ibid., p. 102. (45) Ibid., p. 103. (46) Calgary Herald, 28 December 1993, p. B1. (47) In Ward, the Supreme Court of Canada also noted that claims based on sexual orientation as well as gender would fall into the first category of "particular social group."

|