|

PRB 00-06E

INTERNATIONAL

DEPLOYMENT OF CANADIAN FORCES:

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS LEGAL AND PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS OTHER OPTIONS FOR PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY INTERNATIONAL

DEPLOYMENT OF CANADIAN FORCES: At the end of 1999, more than 4,400 Canadian Forces personnel were deployed overseas in peace support and other military operations. This was the most significant deployment of Canadian military personnel abroad since the Korean War in 1950. Meanwhile, debate within Canada focused on the ability of the military to sustain such operational demands, particularly within the context of a significantly reduced defence budget,(1) a decrease in the number of personnel(2) and highly publicized problems with equipment and morale within the forces. In the Canadian Parliament, the debate has extended beyond these defence department issues to the practice of parliamentary involvement in authorizing the international deployment of Canadian Forces. Some Canadians argue that Parliament should be involved in related discussions much sooner and have more formalized authority over the final decision. Others counter that such requirements would hinder the government’s ability to respond quickly to crisis situations around the globe. This debate was highlighted in a chapter of the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs’ (SSCFA) April 2000 report, whose conclusions and recommendations are reviewed in this paper.(3) To clarify the question of Parliament’s role in the engagement of Canadian Forces overseas, this paper examines: the legal and constitutional authority for the commitment of Canadian military personnel abroad; the process whereby Canada has deployed its military (both in times of war and of peace); and the focus of the debates surrounding those deployments. Ultimately, this paper seeks to explore the appropriate degree of parliamentary involvement in making key defence decisions and how Parliament’s role in such matters can be strengthened without compromising Canada’s ability to respond swiftly and effectively to international crises. LEGAL AND PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS (4) As a matter of Canadian constitutional law, the situation is clear. The Federal Cabinet can, without parliamentary approval or consultation, commit Canadian forces to action abroad, whether in the form of a specific current operation or possible future contingencies resulting from international treaty obligations. Under the Canadian Constitution [Constitution Act, 1867, sections 15 and 19], command of the armed forces – like other traditional executive powers – is vested in the Queen and exercized in her name by the federal Cabinet acting under the leadership of the Prime Minister. As far as the Constitution is concerned, Parliament has little direct role in such matters. Of course, Parliament, especially the House of Commons, plays an indispensable though indirect role by voting or withholding funds and by retaining or withdrawing confidence in the Government of the day. Moreover, short of an actual vote, there are other mechanisms which enable parliamentarians to hold the Government accountable for its decisions and to register their own views. These include questions to Ministers, debates on the Estimates, and “take note debates.”(5),(6) Although Parliament has a specific statutory role in some national emergencies under the Emergencies Act and with respect to the active status of the Canadian Forces under the National Defence Act, Cabinet is only required to seek parliamentary approval in the event of conscription or specific states of emergency. Without consulting Parliament, Cabinet can deploy troops by an order in council.(7) Section 32 of the National Defence Act only “requires that Parliament (unless it is dissolved at the time) be sitting whenever any element of the Canadian Forces is placed on “active service” by the Governor in Council, or within ten days thereafter.(8) Although the Act does not specifically give Parliament any say in the matter,(9) the requirement may reinforce Cabinet’s accountability to Parliament at such times by ensuring that parliamentarians are on hand to question and challenge the government.”(10) The effectiveness of section 32 in this regard can be limited, however, when Cabinet simply issues “blanket” active service orders. For example, the Canadian Forces have been on active service continuously since 1950 in furtherance of Canada’s NATO commitments. Nonetheless, Cabinet has adopted the practice of issuing specific active service orders for major UN deployments.(11) Of course, Cabinet is accountable to Parliament and ultimately to the electorate for its decisions. But given the potentially far-reaching and irrevocable nature of those decisions, it seems reasonable to consider whether the generally ex post facto scrutiny of executive policy in this area is sufficient. After all, legislatures of other countries (for example, the United States and Denmark) appear to have a greater role in foreign policy decision-making than does the Parliament of Canada. Moreover, past Canadian practice also seems to have allowed for more regular involvement of Parliament in foreign policy matters.(12) According to Professor Nossal, “one of the most deeply rooted traditions in Canadian foreign policy is the idea that only Parliament should decide to commit Canadian forces to active service overseas.”(13) The application of this theory to practice – whether for an offensive deployment or for peace operations – has been inconsistent as the analysis of deployments in appendix 1 shows. To complicate matters, since the early 1990s it has become more difficult to distinguish offensive from non-offensive missions, because peace support operations have increasingly become high-risk for personnel. Involvement of Parliament in this decision-making has ranged from no consultation at any time to a full debate and vote in the House before the making of a formal commitment. In many cases, however, debate came only after the government had made its decision, or so close to a deadline that it had little influence on the final decision.(14) Although the current government has increased the frequency of parliamentary debate on deployment, more deployments have been at issue. This may simply reflect the increase in debates. Apparently, the government has not established criteria (such as the size of the force or duration of the commitment) to guide whether a given deployment will be debated or not. In some cases, it was only after opposition parties complained publicly about the lack of parliamentary debate that a government proceeded to hold discussions within the House of Commons. Some would argue that little appears to have changed over the years to strengthen parliamentary oversight in this area. Even individual government-party Members of Parliament outside Cabinet have little input into decisions on the use of the Canadian military, let alone any real power to affect those decisions. Debate on changes in mandates or other actions during a mission are even rarer than those on initial deployment. Typically, mid-mission decisions are not brought back to the House. According to the current Minister of National Defence, this reflects a precedent established in the Second World War and Korea, whereby

To complicate matters further, many decisions must be based on factors beyond Canada’s control: “the reactive nature of Canada’s foreign policy means that much of the agenda is not the Canadian government’s to set.”(16) Unilateral action by other countries (such as the United States), alliances (such as NATO), or multilateral institutions (such as the United Nations), in many instances, make parliamentary input impossible. It would not be diplomatically feasible to withhold all comments on Canada’s position from foreign representatives until after a parliamentary debate, particularly when most such decisions seek to address emerging crises within compressed timeframes.(17) Moreover, “once Canada commits troops, it has written off its right to act independently, and has become just another ‘troop contributing nation’ participating under a common policy adopted by the UN; and Canada becomes ‘locked in’. Subsequent Parliamentary involvement is largely ineffective.”(18) The parliamentary calendar places yet another constraint on Canadian governments’ ability to engage Parliament actively before deciding how to proceed. Professor Nossal notes that, when combined with the “huge distances” that separate many members’ constituencies from Ottawa, the fact that Parliament is not constantly in session renders meaningful input on its behalf into the making of day-to-day foreign policy near impossible: “Instead, the folk who are on duty […] 24-hours a day, 7 days a week, and 52 weeks a year – ministers in cabinet, or, more properly, their officials – are perfectly placed to deal with the unpredictable rhythms of world politics. […] Decisions can rarely wait until the members are reassembled and parliament organized for a debate.”(19) Nonetheless, when the international deployment of Canadian Forces has been debated in the House of Commons, those debates did not typically focus on geopolitical reasons or interests which prompted Canada to become involved (or not). Strong support for a given military operation usually existed across party lines, especially if the mission in question had been authorized by the United Nations Security Council and/or if deployment had already occurred – that is, the engagement of Canadian Forces was de facto. Rather, debate tended to focus on the ability of Canada and the armed forces – given the current environment of limited human, material and financial resources – to take on new commitments. Many challenges to the government revolved around providing adequate equipment and personnel to ensure the Canadian military was not over-stretched and could complete its assignments without causing undue risk, either physical or mental, to it personnel. Questions seemed to focus more on whether Canadian Forces should be deployed if/when they did not have the proper resources to do the job safely, rather than on whether they should be sent at all. Other questions from opposition Members inquired about the details of a deployment (its objectives, degree of risk, size, cost and expected duration), whether appropriate resources were available, and if there were any conditions on participation. Members of Parliament also wanted assurances that all other options had been exhausted and that solutions to the original source of conflict would continue to be pursued. They wanted to know about the government’s long-term plans, particularly in the event of escalation. Of course, the major challenge to the government in most cases was to justify why Parliament had not been consulted or asked to vote with respect to these matters. Typically, opposition parties have not argued against the deployment of Canadian Forces. Ultimately, the problem is seen to be with the political process, not the actual act of deploying troops. In the view of one academic, “when Canadian prime ministers say that parliament will decide such important matters [as the deployment of military forces overseas], they in fact do not really mean it. They do not mean it because they know formal parliamentary approval to be legally and constitutionally unnecessary. … the use of the Canadian Forces abroad, whether to go to war or to engage in peacekeeping, is, in British parliamentary systems, the prerogative of the executive.”(20) Indeed, we are once again faced with the fact that, with the possible exception of a declaration of war,(21) there is no legally required role for the Canadian Parliament to approve Canada’s participation in external military operations, despite attempts to change this situation. In its April 2000 report, the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs considered the lack of parliamentary approval of overseas Canadian Forces’ deployments of Canadian forces to be “unacceptable” and stated that “Parliament should always be consulted […] when Canadian troops are deployed abroad.”(22) It also noted that the 1994 Special Joint Committee on Canada’s Defence Policy and the 1997 Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia had called for enhanced parliamentary oversight of defence matters and made recommendations to that effect, with little impact. In his May 1996 Report, the Auditor General of Canada did the same.(23) In addition, Members of Parliament have used private members’ motions and opposition days in an attempt to require such a vote, at least in the House of Commons, before a decision is made. However, the government has consistently defeated these initiatives. For example, Reform MP Chuck Strahl introduced a private bill, Bill C-295, in the House for first reading on 7 December 1994. The bill proposed amending the National Defence Act to provide for a vote in Parliament before Canada could commit to overseas operations, according to certain basic requirements. For example, the operations would have to be UN-authorized and involve a minimum of 100 CF personnel for at least one month. The mission would have to have specified objectives and duties as well as a clear role for Canada, while the government would have to establish a clear end date and its maximum planned expenditure for that mission. However, it did allow certain exceptions for outstanding circumstances. The bill was defeated on second reading on 19 June 1995.(24) Reform MP Bob Mills’ similar attempt on 23 October 1996 was also eventually defeated.(25) On 10 June 1998, Parliament began consideration of yet another Private Members’ motion (number 380) by Mr. Mills. In speaking to his motion, Mills explained that it had a three-part approach. First, in an information session of two hours, Members of Parliament would sit in the House of Commons as a sort of committee of the whole to hear from military, foreign affairs and academic experts and be informed of the history of the part of the world to which it was proposed troops would be dispatched. Second, in a debate of two hours, speakers from each party would present their party’s opinion on the proposal from a military and foreign affairs perspective. Finally, all Members would vote on whether to deploy CF personnel to the operation under consideration. If passed by the House, the motion would be transferred to a committee, which could then make appropriate adjustments. The opposition parties argued for a change in how information on the activities and commitments of CF was brought to the House, in order to achieve greater accountability, transparency and legitimacy as well as to avoid the “top-down” Cabinet decision approach to engaging CF abroad. The opposition said that special “take note” debates took place too late to influence the outcome and that key players from the government were frequently absent from the chambers for the duration of any such debates; expressed concern about the military’s lack of capability, in view of funding, equipment and personnel deficiencies, to continue to participate so widely around the world; and argued that voting would ensure a more democratic process, involving elected representatives to a greater extent and bolstering formal support for the government’s actions in a true expression of Parliament’s sentiment. The government countered with references to its constitutional legal right to make such decisions independent of the legislature. It maintained that requiring a vote would “handcuff” it and deprive it of the necessary flexibility to respond quickly and decisively to emergency situations through the dispatch of troops on short notice. Government members noted that “additional steps in the deployment process risk[ed] delaying [its] ability to respond”(26) and could compromise alliance commitments under NATO and NORAD. Finally, the government asserted that parliamentary procedure on the issue of military deployments had progressed significantly and would continue to do so without requiring a formal vote. As an example, it cited the practice that had emerged of consulting Parliament (when it was in session) through “take note” debates in which all Members had an opportunity to express their views. Moreover, the government had attempted to involve all parties in its decision-making even when Parliament was not in session: during the situation in Haiti (when Parliament was in recess), the government informed the appropriate porte-parole from each of the opposition parties of the government’s intentions and requested their agreement for action without recalling Parliament. The government also pointed out that it had pursued other means of involving Parliament in its decisions, such as having Ministers appear before standing committees. The motion was debated in the House on three separate occasions (10 June 1998, 29 October 1998 and 4 February 1999) before being defeated on 9 February 1999, despite support from most members of all four opposition parties. Later, on 19 April 1999, during its allotted day, the Bloc moved

Their main complaint was with regard to the lack of ongoing information about the mission. The Liberals responded that the motion was “imprecise at best” and that, if the House did not support the government, the opposition should introduce a motion of non-confidence. Government members further argued that the motion: dealt with a hypothetical situation; would set an unworkable precedent by requiring micro-management of the mission, thereby undermining day-to-day efficiency; and would hinder the deployed forces’ ability to respond swiftly and flexibly to new crises. Ultimately, the motion failed to pass. The most recent attempt on record to have a compulsory vote came, interestingly, from the Senate. The Upper House’s Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs has argued that

Consequently, the Committee recommended

The government has not yet responded to the report. Given the preceding examples, however, one might conclude that the government will resist any attempt to place constraints on its ability to act freely and avoid micro-management in the matter of deploying Canadian forces internationally. OTHER OPTIONS FOR PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY The most obvious, although limited, means of exercising Parliament’s authority over the international deployment of Canadian Forces consists of its ability to withdraw confidence from the government in the House of Commons and to refuse to do the government’s supply (money) business.(30) As long as Parliament uses neither of these powers, it implicitly approves the government’s exercise of its executive powers.(31) To withdraw support or deny a supply bill would be difficult, however, in view of a government majority and the claims of party loyalty. Furthermore, as the Senate committee notes: “denying funds to the Government and withdrawing confidence are rather blunt instruments for expressing dissenting views on such issues. Moreover, the opportunities for scrutiny and dissent that are offered by the Supply process cannot always be used in an effective or timely fashion. In the case of Kosovo, for example, it was only in November 1999, five months after the action had ended, that Parliament had an opportunity to vote funds expressly earmarked for that opposition.”(32) Alternatively, Parliament can be involved in decisions to deploy CF by other means, for example, through hearings in committees and briefings by public officials. (It has been noted that Committee activity has increased since 1969.(33)) Standing committees have already been used as a forum for more ample debate on international deployments. For example, in April 1998, a special joint meeting of the House standing committees on foreign affairs and defence was held to discuss possible Canadian participation in a peacekeeping force in the Central African Republic. As a member of the government explained: “This option was chosen because of the need to make a decision and deploy troops as rapidly as humanly possible. Both ministers attended the special meeting and a unanimous resolution in favour of Canadian assistance was adopted.”(34) In addition, the Department of National Defence makes available a monthly update of its “D PK POL Peace Support Operations SITREP.” This non-classified document identifies those peace support operations since 1945 to which the Canadian Forces have provided personnel, their role, and the size and duration of the commitment. It also mentions operations in which Canada has chosen not to participate. Regular reporting by the Department to, and scrutiny of, this list in the House of Commons Standing Committees on National Defence and Veterans Affairs (SCONDVA) and on Foreign Affairs and International Trade (SCOFAIT), as well as the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs (SSCFA), would ensure some awareness among parliamentarians of Canada’s military commitments overseas. The Department has also begun to offer occasional operational briefings which may be of interest to committee members and, indeed, all parliamentarians. (Transcripts of these briefings are available on the DND website.) Finally, the House committees regularly review their respective department’s Main Estimates. This exercise provides an excellent opportunity to scrutinize both departmental planning and budgeting and to comment accordingly. In its April 2000 report, the SSCFA acknowledges the importance of this and recommends that it be afforded the same opportunity.(35) In 1999, a defence analyst commented on the view that “Canadian politicians are not interested in defence policy. Neither are they conversant with nor much interested in the Canadian Forces, except in a kind of folksy regard one has for the family pet.”(36) The vibrant debate over Parliament’s role in the international deployment of the Canadian Forces, however, suggests that Canadian politicians want very much to have a say in how the military is used to fulfil Canada’s foreign policy. Furthermore, it is ultimately the responsibility of Parliament to hold the government accountable for its decisions, including those related to military operations.(37) Evidently, practice has been inconsistent on this matter. Even the current practice of holding “take note” debates that do not involve a vote is applied erratically and without a clear rationale. One academic concluded that:

Indeed, constitutional requirements are not likely to change. As long as a majority government holds power and opposes a mandatory vote, it is improbable that any attempt at change will succeed (unless it is initiated by the governing party itself). This does not preclude greater parliamentary involvement through other means, such as scrutiny in committees, review of the Estimates, and so forth. In addition, recent changes implemented by the government have moved toward greater all-party involvement and input on deployment of forces (although not always before a decision is made). As a minimum, Members of Parliament (and Senators) can insist that they be provided with as much information on engagement as possible – on the mandate, terms and objectives of a mission, risk factors, number of Canadian troops to be employed, duration, cost, other participants, and Canada’s interest in the region – before any debate takes place. “Effective oversight need not derive from Parliament micro-management of Cabinet. Rather, the key to effective oversight is proper information to Parliament.”(39) One thing is certain – the debate will continue. APPENDIX 1 COMBAT AND OTHER DEPLOYMENTS To analyze parliamentary input into the international deployment of Canadian Forces (CF), a number of criteria must be established to distinguish between such cases as recent military action involving the Canadian Forces in Kosovo under NATO and peacekeeping operations under United Nations’ auspices. With regard to the type of tasks carried out, the NATO-led mission in Kosovo would be more appropriately grouped with the Persian Gulf War, the Korean War, and the First and Second World Wars, in which Canadian military personnel were used for combat, as opposed to exclusively neutral or humanitarian, tasks. Similar criteria have been applied to distinguish Canadian participation in Somalia under the United States-led UNITAF from the UN-led UNOSOM. One could assume that Parliament’s oversight of combat deployments would be more significant. 1. Combat Deployments (40) a. Boer War Under the government of Wilfrid Laurier, Cabinet decided in October 1899 on Canadian participation in the Boer War. Parliament had no role in this decision.(41) b. World War I Britain declared war on 4 August 1914. Under the government of Robert Borden, by orders-in-council on 6 and 10 August (while the House of Commons was not sitting), Canada made a commitment to send an expeditionary force to Europe. Subsequently, Prime Minister Borden reconvened Parliament early to hold a special war session from 18 to 22 August 1914. During this special session, the House “unanimously confirmed the actions of the executive” by debating and adopting a motion to approve the address in the reply to the Speech from the Throne presented on 18 August, which had indicated “the measures the government would take to deal with the war.”(42) c. Russian Civil War In his testimony before the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Professor Nossal noted that, “in August 1918, the Borden government authorized the dispatch of a field artillery brigade […] and in October 1918 the government approved the sending of a force of some 4,000 men to Siberia. In neither case was Parliament consulted by the Borden government, and no debate of the Canadian intervention in Russia took place.”(43) Some might argue that this incident was an offshoot of the Great War, which had already been debated in the House of Commons, and thus did not require further consultation with Parliament. d. World War II Conversely, “in 1923, Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King declared that only Parliament should ultimately decide on Canadian participation in foreign conflicts:”(44)

In keeping with this assertion, Cabinet, although it had decided that Canada would side with Britain, agreed on 24 August 1939 that no firm decision would be made before war actually broke out.(46) When the war started in Europe, Parliament was not in session and was not scheduled to return before 2 October; however, it resumed sitting on 7 September 1939. As in 1914, the Governor General read a Speech from the Throne; and Parliament debated an Address in reply to the Speech from the Throne. During this debate, which began on 8 September, Prime Minister Mackenzie King explained that Parliament’s approval of the Address in reply to the Speech from the Throne would pave the way for a formal declaration of war. The motion to adopt the Address was passed in the Senate while the House of Commons continued debate on the motion and adopted it late in the evening of 9 September. No specific time frame for declarations of war or similar statements was set by the course followed in 1939, but the practice of having both Houses of Parliament adopt an Address in reply to the Speech from the Throne was confirmed and a new precedent was set for the sequence of events leading up to the issuance of the order-in-council. In 1914, the order-in-council had been proclaimed the day the war started and parliamentary debate followed; however, in 1939, parliamentary debate preceded the order-in-council declaring war. This was the procedure followed when war was declared on Italy in 1940.(47) Subsequent declarations of war by Canada during the Second World War [against Japan, Hungary, Romania and Finland] took place without any parliamentary debate,” as they were considered “all part of the same war.” “The Debates of the House of Commons do not indicate that the opposition objected to the fact that Parliament had not been reconvened to adopt motions concerning the declarations of war on Japan, Hungary, Romania and Finland. Indeed, there was generally little criticism of the process the government followed to indicate formally that Canada was at war.(48) e. Korean War Although the declarations of war during the First and Second World Wars established a number of parliamentary precedents, a completely different set of circumstances has prevailed since 1945 when the United Nations Charter was signed; Canada has participated in a number of international conflicts, but has never declared war. The process through which this came about can be understood by looking at how Canada became involved in the Korean conflict between 1950 and 1953. Following North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950, the Security Council of the United Nations passed a resolution requesting member countries of the UN to assist South Korea in dealing with North Korean aggression and to re-establish peace in the region. On 26 June, Secretary of State for External Affairs, L.B. Pearson made a statement in the House of Commons concerning the Korean situation and read into the record the text of the Security Council resolution.(49) On 27 June, following the UN decision to respond to the invasion with force, the Canadian Cabinet met. Shortly thereafter, the Prime Minister invited opposition leaders into a special conference, an unusual development. Subsequently, on 29 June, after a full debate in the House of Commons, all but one MP supported the government’s decision to join in the multilateral use of force.(50) On 30 June, Prime Minister St. Laurent, commenting on the Korean situation and the Security Council resolution, said:

He continued:

In short, the Prime Minister made it clear that Canada was ready to send military personnel and equipment to help South Korea deal with the aggression if the United Nations considered such action necessary. Canada would not have to declare war on North Korea.(52) When Parliament returned on 29 August 1950, it was for a special session that dealt with a national railroad strike, as well as with the situation in South Korea; however, the Speech from the Throne made it clear that the Korean situation was the main purpose. The Canadian government wanted a rapid expansion of Canada’s military forces as a whole, as well as an increase in the number of Canadian personnel involved in the Korean police action. Thus, the government introduced new legislation, including the Canadian Forces Act to amend the National Defence Act and the Defence Appropriation Act to increase the defence budget. The special session of Parliament did not, however, debate or pass a motion specifically dealing with the government’s decision concerning Canadian participation in UN police action in Korea. Indeed, during debate on the Canadian Forces Act, an opposition Member asked the Prime Minister if there would be a resolution authorizing the sending of troops to Korea. Mr. St. Laurent replied:

The Defence Appropriation Act was passed by Parliament, thereby authorizing the ways and means for the government to carry out its policy on the Korean conflict.”(54) f. Gulf War (U.S.-led) Because the measures taken against Iraq, like those against North Korea in 1950, did not require Canada to declare war, it was not necessary for Parliament to debate a declaration of war. It was also within the powers of the government, without recalling Parliament, to authorize other actions taken by Canada shortly after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. For example, when on 6 August 1990 the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 661, which made it mandatory for UN members to impose strict economic sanctions on Iraq, the Canadian government did so by invoking the United Nations Act, which stipulates only that any orders and regulations made under it will be tabled as soon as Parliament returns.(55) However, on 23 October 1990, the House of Commons was asked to and did approve a motion that affirmed support for the “sending of members, vessels and aircraft of the Canadian Forces to participate in the multinational military effort in and around the Arabian Peninsula.”(56) Then, on 29 November 1990, the UN Security Council passed resolution 678, authorizing the use of force against Iraq after a 47-day “pause for peace” (ending 15 January 1991). That same day, the House of Commons passed a further motion supporting “the United Nations in its efforts to ensure compliance with Security Council resolution 660 and subsequent resolutions.”(57) Finally, as the 15 January 1991 deadline approached, the government recalled Parliament from recess for an emergency debate on a government motion to “reaffirm [the House of Commons’] support of the United Nations in ending the aggression by Iraq against Kuwait.”(58) The debate focused on whether Canada should participate in a non-UN-led mission, especially one that was offensive in nature. Opposition parties questioned the merits of the United Nations’ aggressive response to the Iraq/Kuwait situation, because it had failed to act at all in other similar circumstances. The non-government parties also claimed that it was premature to wage war before all other options (sanctions, diplomatic negotiations, etc.) were exhausted. The official opposition even attempted (unsuccessfully) to amend the government’s motion “to exclude offensive military action by Canada at [that] time.”(59) However, the debate was made moot with the United States’ initiation of hostilities on 16 January. Despite this, all parties agreed to allow the debate to continue. The government’s original motion was passed unchanged on 22 January 1991. By this time, all parties had stated their support for the Canadian troops in the Gulf (while urging the government to pursue an end to the conflict).(60) Although there was no formal declaration of war, Parliament debated Canada’s participation in the Persian Gulf conflict and passed motions approving the measures taken in accordance with United Nations police action. Parliament was also advised that Canadian Forces personnel had been placed on active service. The procedure followed was not exactly the one used in 1950 for the other UN police action, but in 1990-1991, Parliament passed specific motions and was thus more directly involved. The need for motions to reaffirm previous motions in 1990-1991 arose from the complexity of the Persian Gulf issue and the controversy it generated. The fact that a further resolution was called for “in the event of the outbreak of hostilities involving Canadian Forces,” even though the military personnel had already been placed on active service, created an important precedent. Parliament passed not only a motion to approve the government measures (such as deploying troops) taken to deal with the conflict, but also a motion to approve the actual participation of Canadian Forces personnel already in the combat zone.”(61) g. Somalia (U.S.-led) The United Nations Security Council by resolution 794 approved a United States-led enforcement mission to Somalia (UNITAF) on 3 December 1992. This effectively changed the mandate of UNOSOM (the preceding peacekeeping mission) and approved the use of force. The next day, a member of the Opposition called for debate in the House of Commons before the government made its final decision. The Secretary of State for External Affairs (SSEA) answered that the government would make an announcement reflecting its decision later that day and that, thereafter, there would be “a discussion in Parliament as to the implications of that decision.”(62) Three days later, another opposition MP stated that “a decision to send troops into a war zone is a major one that should be debated by Parliament before the fact” and that “this decision [on Canadian participation in UNITAF] was made without consulting Parliament, without debate.”(63) To this, the SSEA replied that:

However, later the same day, the government held a special debate and moved to “affirm [the House of Commons] support … for Canadian participation in the multinational effort … in Somalia.”(65) The motion passed. During the debate, the opposition parties questioned what Canada’s commitment involved, whether the Canadian troops would be fully supported and properly equipped, and whether the government had explored a long-term solution to the conflict. Although they ultimately supported the UN decision, as well as Canadian participation in the mission, they opposed what had taken place within Parliament. One Member suggested that Canada “need[ed] to have either a combined committee of the Senate and the House or a combined defence and external affairs committee … a standing institutionalized system of parliamentary watch on this operation” and others.(66) h. Kosovo (NATO-led) The government first consulted the House of Commons on the situation in Kosovo on 30 September 1998, when it moved that the House “[express] its profound dismay and sorrow concerning the atrocities being suffered by the civilian population in Kosovo and [… call] on the Government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the parties involved in this inhumane confrontation to put down arms immediately and start negotiating a solution.”(67) The motion was agreed to, although not put to a vote. A week later, on 7 October 1998, the government held a “take note” debate in which the House noted “the dire humanitarian situation confronting the people of Kosovo and the government’s intention to take measures in cooperation with the international community to resolve the conflict, promote a political settlement for Kosovo and facilitate the provision of humanitarian assistance to refugees.”(68) At that time, the opposition parties questioned the government about how far it intended to go, what dangers the Canadian troops would face, whether they were ready and properly equipped for another operation, and whether the international community (or even the Canadian government itself) had developed a long-term plan or established its political and military objectives. Members also expressed concern about the legality of any action that had not been authorized by the United Nations and the possible negative implications of such action on the international organization. As this would be the first time that Canada had participated in a foreign conflict without UN authorization since the organization’s creation in 1945, many Members would have preferred to await a resolution in the Security Council. When questioned further about the possibility of military action, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy, stated that he did “not think it would be very appropriate … to outline what the steps [of military action by NATO] would be until the decisions [were] taken.”(69) Indeed, the wording of the government’s motion left the term “measures” undefined so that the possibility of military involvement was neither specified nor excluded. In a later debate, one opposition MP would note that the government used this debate “to claim it was entitled to take part in air strikes” with the House’s support, although he did not believe this to be a valid assertion.(70) A second “take note” debate took place on 17 February 1999, when the House noted the possibility of “Canadian peace-keeping activities in Kosovo.”(71) The debate focused on peacekeeping and did not contemplate the combative role the Canadian Forces eventually played in the confrontation. After NATO airstrikes began in Kosovo on 24 March 1999, opposition Members berated the military and the government in general, specifically the Minister of National Defence, for not holding briefings and a debate on the escalating situation. The Prime Minister subsequently announced to the House that the Ministers of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and of National Defence (MND) had discussed the situation with the respective parties’ critics.(72) Later that day, following a joint statement by the MFA and MND,(73) each party’s critic made a statement. The discussion focused on what would happen next and whether Canadian troops would become further involved. The opposition parties sought assurances for the safety of CF personnel and that their equipment was adequate for the tasks they would be given. They also pressed the role of Parliament in the whole issue and demanded that the House of Commons be consulted in the event that the situation escalated (for example, if ground troops were to become involved). The earlier debates in November and February had not dealt with future escalations. Regular briefings were held at the Department of National Defence, (DND) and officials from DND and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) presented weekly (and sometimes twice-weekly) updates and took questions at combined meetings of the Standing Committees on Foreign Affairs and International Trade and on National Defence and Veterans Affairs. The government held a third “take note” debate on 12 April 1999, asserting “the government’s determination to work with the international community in order to resolve the conflict and promote a just political situation that leads to the safe return of the refugees.”(74) At that time, the Minister of National Defence committed “that if there were any substantive change in terms of [Canada’s] involvement in this matter [… the government] would come back to the House for discussion.”(75) A week later, during Oral Question Period on 19 April 1999, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien asserted that “depending on the nature of the request [i.e., to deploy Canadian ground troops in Kosovo under NATO], I will advise if we should or should not have a vote.”(76) In other words, while he reserved the right to decide whether a vote would be held, he did not rule it out as a possibility. Ultimately, ground troops were never requested and no other “take note” debate was held, nor any vote. B. Other Operations: Peace Support, etc. The changing nature of peace support operations means that they are more complex and often more dangerous than traditional peacekeeping. One can make distinctions between operations according to the size of the deployment, the proximity of CF personnel to combat zones, and the resulting level of risk in theatre. In addition, particularly with regard to missions that span several years (even decades), it is important to consider that CF contingents may have been augmented significantly or tasked with different responsibilities at various points in time – as is the case in the former Yugoslavia. Such changes would, one assumes, be of as much interest to Parliament as proposed involvement at the onset of an operation and would require equal debate; recent precedent seems to confirm this. The analysis below is not by any means exhaustive; Canada has been involved in more than 40 peace support and related operations since 1945. The sample cases serve only to highlight the different approaches to parliamentary involvement in the authorization of international deployment of Canadian Forces. Appendix 2 to this paper lists Canadian military participation in peace operations since the end of the Second World War, and notes whether and when those deployments were formally debated in the House of Commons. Furthermore, to establish unequivocally whether Parliament has (1) been consulted before or after a decision to deploy and (2) voted on the deployment of Canadian Forces personnel, one would need to know the exact dates of commitment of forces and/or deployment. Unfortunately, this information is not readily available from the Department of National Defence(77) and, as a result, in many cases it is impossible to determine whether a debate or vote occurred prior to deployment. Consequently, analysis focuses more on the wording of the motion before the House (if any was presented) and the content of the debates. 1. Creation of the United Nations (1945) to October 1993Although the UN Charter does not oblige Canada to participate,(78) Canada has a strong tradition of providing personnel and resources to United Nations’ operations. Canada has also been active in numerous other international efforts to restore or maintain, monitor and reinforce peace in many parts of the world. a. Indochina Commissions Following the war in Korea, Canada was nominated to serve on the three truce supervisory commissions. Without any reference to Parliament, the Canadian government committed itself to this service on 28 July 1954.(79) b. Suez Canal On 2 November 1954, while Parliament was not sitting, Prime Minister Pearson offered Canadian forces to the General Assembly for a peace mission in the Suez Canal. Subsequently, on 26 November, well after Pearson had fully committed the Canadian forces, the government convened a special four-day session of Parliament to consider the matter.(80) c. Cyprus According to Professor Nossal, Canada’s long involvement in Cyprus also began when Parliament was not sitting: in mid-February 1964, Prime Minister Pearson made a private commitment to the British prime minister and forces were put in training.(81) Pearson had promised that no troops would be committed without parliamentary approval, however. Consequently, on 13 March 1964, he moved that the House of Commons “approve the participation of Canadian forces in the United Nations international force in Cyprus.”(82) During the debate, the Leader of the Opposition, J.G. Diefenbaker, recalled the principle detailed in 1925 by Arthur Meighen – that Parliament should decide on the participation of Canadian troops abroad. He noted that, though this view had not been generally accepted, the current request for the House’s approval could be seen as a further step towards the establishment of the principle.”(83) Ultimately, the motion was agreed to, on division. The House even went one step further to request concurrence from the Senate on the matter.(84) However, Professor Nossal notes that Canadian troops had already been dispatched for service in Cyprus “fully two hours before the honourable members began debating the motion.”(85) Furthermore, the withdrawal of Canadian troops from the mission in December 1992 was also an exclusive decision by Cabinet, made without debate. d. Vietnam Between 28 January and 31 July 1973, Canada contributed 240 military personnel and 50 officials from the Department of External Affairs to Vietnam under the International Commission for Control and Supervision. A review of the House of Commons’ Debates shows that the issue of Canada’s response to the situation in Vietnam was first raised on 4 January 1973, when Prime Minister Trudeau gave notice of the government’s intention “to have this matter debated in the House,” a motion to that effect having already been presented on notice.(86) Opposition parties welcomed his suggestion that the House leaders of the various parties meet to discuss the motion before the matter was debated. The text of that motion acknowledged the possibility “that Canada [would] be called upon to play some new supervisory role following the cessation of hostilities in Vietnam,” but neither explicitly stated nor sought House approval of Canadian participation.(87) A few weeks later, during Oral Questions, the Hon. Mitchell Sharp (Secretary of State for External Affairs) expressed his “intention to bring the matter before the House of Commons at least for debate,”(88) but reserved the right of the government to inform the House of its decision. Again, on 24 January, Sharp asserted that the government wanted the matter “to be discussed in Parliament” and would be introducing a resolution to provide for such a debate. At this time, he was careful to emphasize that Canadians would not “keep the peace,” but rather “observe,” “report” and, potentially, mediate.(89) Once again, however, Sharp indicated that the government reserved the right to dispatch Canadian personnel before the matter came before the House, if necessary, for expediency’s sake.(90) In fact, military and civilian personnel were deployed to Vietnam on 27 January before any formal debate in the House on that specific issue. The issue was discussed at length on 1 February 1973; however, the motion proposed by Mr. Sharp did not request approval by the House and affirmed that the government had already committed (and indeed deployed) the personnel in question.(91) Sharp further asserted that the “House had already had the opportunity for a preliminary exchange of views before [the troops’] departure from Canada” and that “[w]hichever decision is made [by the Government] will be conveyed to this House” as opposed to debated or voted upon.(92) At that time, Members of the opposition recalled the 1964 action for the deployment of troops to Cyprus. One of them argued that “parliament, being the elected representative body of the nation as a whole, must have a voice – indeed a deciding voice – whenever there is proposed a long-term commitment of Canadian personnel overseas,” a principle which “goes back a long way in parliamentary history.”(93) Another commented on Parliament’s responsibility for the safety of Canadian personnel abroad. Yet another observed that, although he did not dispute that the government was required to act without consulting the House for expediency’s sake, he hoped that future developments of the mission, including its possible extension after the initial 60-day period, would be debated in advance of a government decision.(94) In vain, others called for, and continued on later dates to call for, a vote.(95) The resolution calling for a debate and vote was left dormant on the Order Paper.(96) Later, when the government was considering withdrawing Canadian participation from the supervisory force, the opposition again asked for the matter to be brought to Parliament before a decision was taken. Again, the Secretary of State for External Affairs maintained that it was his intention, “as soon as the government makes a decision, to bring that decision before the House of Commons.”(97) In other words, he continued to assert Cabinet’s prerogative on the matter, i.e., the government is responsible for making a decision and for bringing it before the House only for consideration, not approval. e. Golan Heights In 1974, Canadian Forces personnel were deployed in the Golan Heights under UNDOF. This is one of Canada’s most consistent larger deployments with the maximum contribution listed as 230 personnel and current Canadian involvement at approximately 190 CF personnel. However, although there seems to have been ample debate on the Canadian deployments under UNEF I in 1956 and UNEF II (Sinai) in 1973,(98) no specific reference to UNDOF has been found in the House of Commons’ Debates. f. “Desert Shield” (Embargo Enforcement in the Persian Gulf) Following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990, Prime Minister Mulroney committed Canadian forces to the operation during a dinner with U.S. President Bush on 6 August. According to Professor Nossal, Mulroney returned home the next day and “ordered preparations for Canadian Forces naval units to be committed to the multinational force taking shape. These decisions were taken without reference to the Minister of National Defence who was out of the country, or the Secretary of State for External Affairs who was out of Ottawa. When cabinet met on 8 August, […it] approved Mulroney’s commitment. The House was not in session, and Mulroney had no intention of calling it back [because of the domestic crisis at Oka].”(99) After the ships had already been committed, the government sought parliamentary approval in a debate on 24 September 1990, which was resumed on 17-18 October. “When the vote did come a month or two later, it was not to authorize troops or ground involvement, it was simply a vote to endorse a UN resolution.”(100) Therefore, the current government has argued that this case does not create a precedent. g. Somalia (UN-led) Although debate in Parliament did address the deployment of some 1,300 CF personnel to Somalia under UNITAF in December 1992 (discussed above), the House never discussed an earlier deployment to the same country, whereby 750 military personnel were engaged under UNOSOM. This earlier commitment was simply announced by the Minister of National Defence on 28 August 1992. The Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of National Defence tabled an Order-in-Council (P.C. 1992-2006 dated 8 September) on 14 September 1992, placing the members of the CF on active service for the United Nations operation in Somalia, without debate. 2. October 1993 to Presenta. Former Yugoslavia The Canadian deployments to the former Yugoslavia have been by far the most debated international deployments in Canadian history. Canadian involvement in the numerous peace support missions to the Balkans – whether in Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo or elsewhere, under the United Nations or under NATO – have been, as a group, debated in the House of Commons no less than seven times in five years. More than 2,000 peacekeepers served in the Balkans with UNPROFOR and UNPF; still others served with UNCRO, UNPREDEP, UNMIBH, UNMOP, IFOR and SFOR. The first “take note” debate, on 25 January 1994, examined “the political, humanitarian and military dimensions of Canada’s peacekeeping role, including in the former Yugoslavia, and of possible future direction in Canadian peacekeeping policy and operations.”(101) This debate came well after Canadian forces had been deployed to the region under at least two separate missions since as early as February 1992, a fact which the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, André Ouellet, noted in his comments introducing the debate: “when the previous government decided to send troops to the former Yugoslavia, there was no debate, Parliament was not consulted.”(102) At that time, Minister Ouellet also stated that the debate was in line with his government’s “commitment to consult with members of Parliament before making any serious and momentous decisions.”(103) He then detailed the broad guidelines Canadian governments had used traditionally for decisions on whether to participate in a given peace mission, and which his government considered still valid:

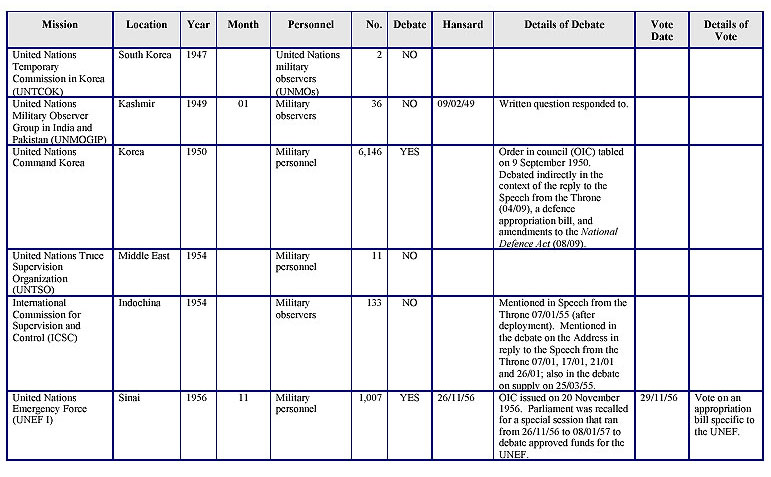

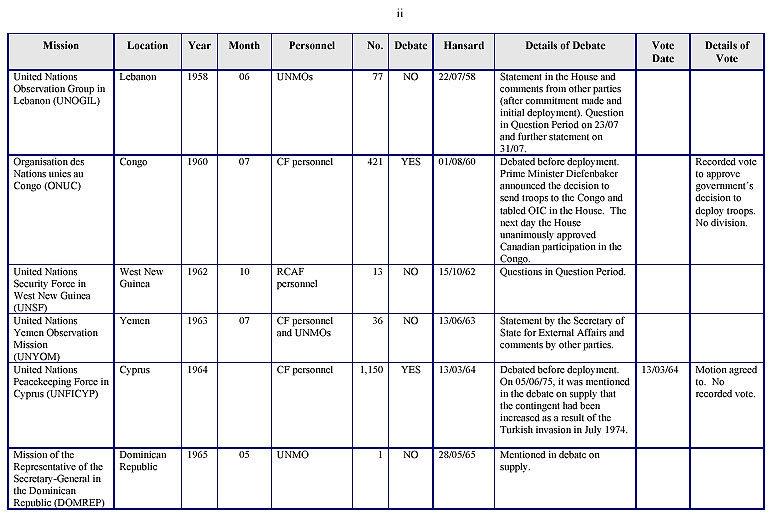

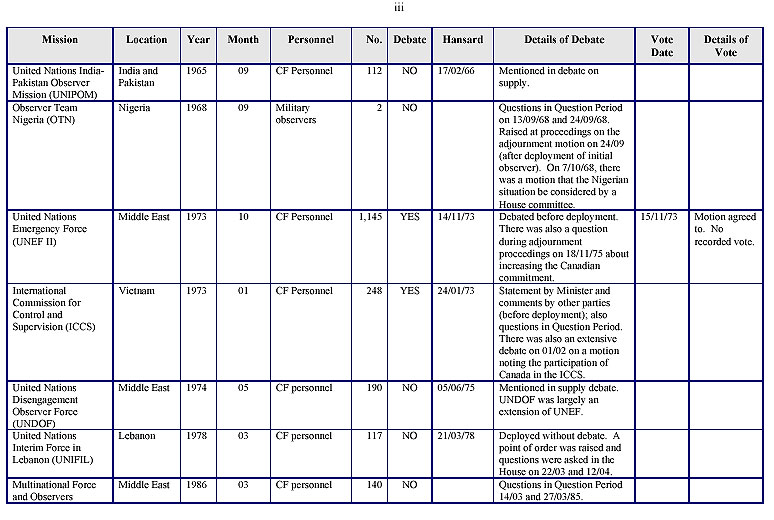

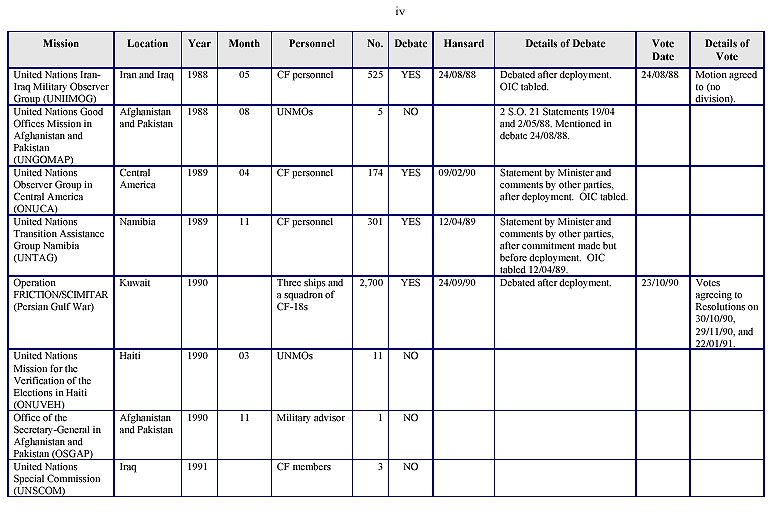

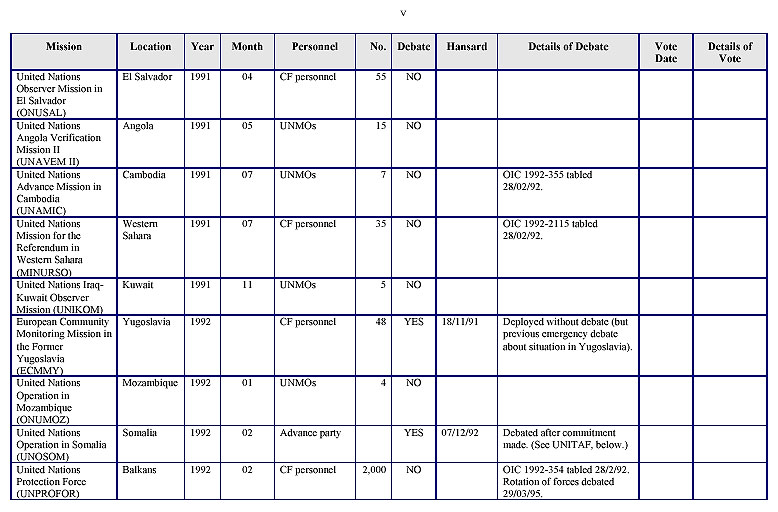

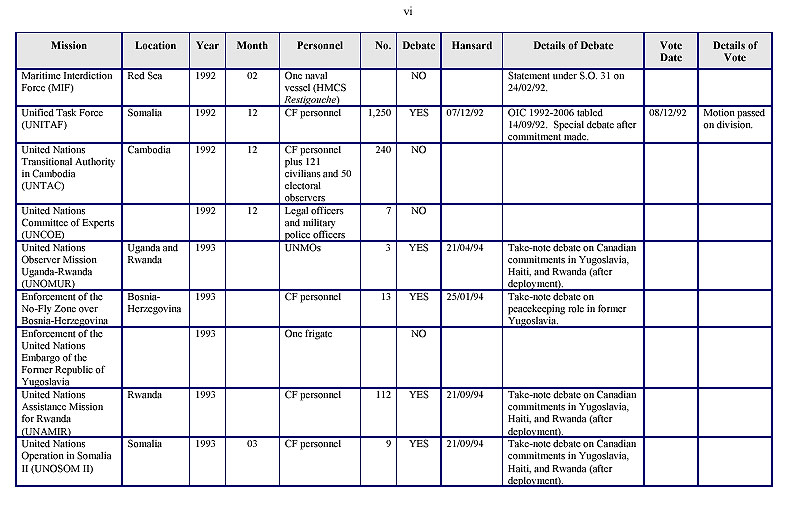

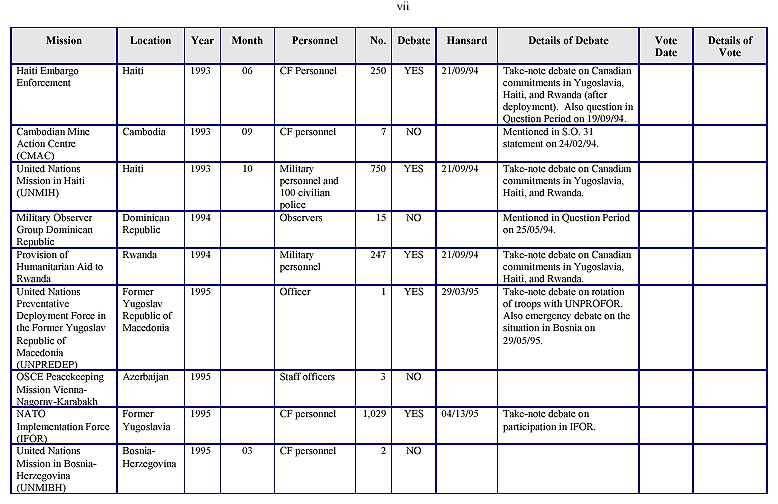

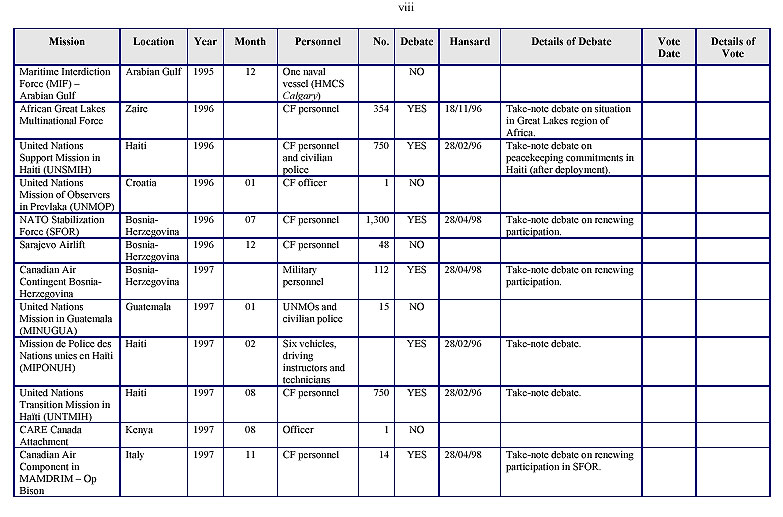

To these guidelines, he added the level of risk incurred by Canadian soldiers. Following Ouellet’s assertion that “the views of the House and of the public generally are of critical importance to [the government’s] deliberations” on the future of its peacekeeping commitments,(105) the debate that ensued was wide-ranging, covering almost all aspects of the guidelines. On 21 April 1994, the government initiated a second “take note” debate. Further to NATO’s agreement in February to a UN request for air support to protect the safe area around Sarajevo, Parliament was asked to “consider the request contained in the UN Secretary General’s April 18 letter to [NATO] to extend arrangements … to the five other UN safe areas in Bosnia.”(106) In the course of the debate, the government found significant support among all parties for the request. The third “take note” debate on Canada’s commitment in the former Yugoslavia did not focus exclusively on that mission; Parliament was asked to note “Canada’s current and future international peacekeeping commitments in this world, with particular reference to the former Yugoslavia, Haiti and Rwanda.”(107) Again, because of the broad parameters given for the debate, the discussion was wide-ranging. The official Opposition established its own criteria for evaluating the desirability of Canadian participation in peace support missions and concluded that the country should not have become involved in many missions then underway.(108) A related conclusion was that Canada needed to be more selective about when to participate, particularly in view of the cost of overly-ambitious operations to Canadian peacekeepers’ physical and mental health, in line with Canada’s resources and capacities. With the UNPROFOR mandate due to end on 31 March, the House of Commons was asked on 29 March 1995 to “take note of the rotation of Canadian forces serving with UNPROFOR in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia.”(109) Then Minister of National Defence, David Collenette, opened the debate stating that the government had yet to decide how it would proceed. Some members of the opposition complained that the debate was on such short notice that it could neither have a real impact on the government’s decision nor allow their parties to prepare properly for the discussion.(110) Nonetheless, the government appeared open to considering various options, from a renewal of its commitment to scaling back or withdrawing from the mission. Later, an opposition member requested an immediate emergency debate on the situation in Bosnia, where Canadian soldiers had been taken hostage. The government initially refused the request, but later relented. The debate of 29 May 1995 focused on whether and how to withdraw Canadian peacekeepers from that area. On 4 December 1995, the House of Commons debated the Canadian contribution to the NATO-led multinational military implementation force (IFOR) established as part of the Dayton Accords.(111) Subsequently, on 6 December, the government announced Canada’s commitment. Professor Nossal notes, however, that “the government had already tentatively offered an infantry battalion and a headquarters unit at a NATO planning session the week before the parliamentary debate.”(112) Almost two and a half years later, on 28 April 1998, the House of Commons was again asked to “take note” of the government’s intention “to renew its participation in the NATO-led stabilisation force (SFOR) in Bosnia beyond 20 June 1998.”(113) This debate took place well in advance of the proposed deadline and can realistically be considered to have informed the government’s decision on how to proceed. b. Iraq On 9 February 1998, the House of Commons debated potential military action in response to Iraq’s refusal to comply with UN-authorized weapons inspections. The Prime Minister had assured Parliament that Canada would make no commitment until that public debate had taken place. However, in a confusing development, the U.S. Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, announced Canadian support for the mission, which would use substantial military force against Iraq, on 8 February, a full day before the matter was been discussed in the House. The Prime Minister maintained that Ms. Albright had been misinformed.(114) c. East Timor On 15 September 1999, Prime Minister Chrétien announced that Canada would contribute up to 600 troops to a peacekeeping mission in East Timor (INTERFET), as well as humanitarian assistance. There was no prior debate in the House on this action (apart from Question Period). Two days later, Ministers Lloyd Axworthy (DFAIT), Art Eggleton (DND), and Maria Minna, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) testified on the situation in East Timor before a joint meeting of the House of Commons Standing Committees on National Defence and Veterans Affairs and on Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The Department of National Defence announced that Canada’s contribution to INTERFET could consist of two Hercules transport aircraft (with 100 support crew, including four six-person crews), one supply ship (with 250 crew), and a reinforced infantry company of about 250 personnel and 40 light vehicles. The Minister further indicated that the incremental costs of deploying all three elements for a six-month period were estimated at $33 million, funds that he would need to seek from the central treasury. On 21 and 23 September 1999, the first groups of Canadian forces personnel – the crews for the Hercules transporters and the HMCS Protecteur –deployed for East Timor. There was no formal debate on these deployments in the House of Commons. d. Other “Take Note” Debates As mentioned above, Canada’s commitment to peace support missions in Haiti and Rwanda were debated under a general motion that included the former Yugoslavia, on 21 September 1994. During that discussion, some opposition members questioned the desirability of continuing Canada’s participation in these missions. The debate on Canada’s commitment in Haiti was renewed on 28 February 1996 when the House was asked to “take note of Canada’s current and future international peacekeeping commitments in Haiti, with particular reference to Canada’s willingness to play a major role in the next phase.”(115) For the most part, all parties supported continued Canadian participation in peace efforts there. Perhaps one of the most significant “take note” debates was that concerning “Canada’s leadership role in the international community’s efforts to alleviate human suffering” in the Great Lakes region of Africa on 18 November 1996. Questions from the opposition parties focused on: the cost of and whether Canada had an appropriate level of military capability to undertake the mission; whether there was international support, particularly in the destination country, for Canadian participation; what the exact mandate of the mission would be and what role Canadian peacekeepers would play under the rules of engagement; and whether the government had established a timeline and an exit strategy, should the need arise, as well as a rotation schedule to ensure the health of Canadian Forces personnel. Although the mission ultimately did not materialize, this debate allowed for an thorough discussion of the facts and an exchange of related concerns. Finally, there was the 17 February 1999 debate, in which “possible changes in peacekeeping activities in the Central African Republic” were considered concurrently with the possibility of Canadian peacekeeping activities in Kosovo. One could argue that debates that address multiple missions, such as that of 21 September 1994, do not allow for an in-depth analysis and discussion of the merits of each individual case. APPENDIX 2

(1) Down 21.5% from FY93/94 to FY98/99. (2) Down 17,675 (22.7%) from 77,975 military personnel in FY93/94. (3) Although this document includes the findings of the Senate committee, its principal focus is on the debates and votes in the House of Commons. (4) Much of this section comes from: Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs [hereafter, SSCFA], The New NATO and the Evolution of Peacekeeping: Implications for Canada, “Chapter VIII: Parliament and Canada’s External Security Commitments,” April 2000. (5) A “take note debate” is a debate on a motion, which says that the House takes note of an issue. This kind of debate merely allows Members to express their views; the motion does not require a vote. (6) SSCFA, p. 71. (7) SSCFA contains a more in-depth analysis of Parliament’s statutory roles, p. 1-72. Also see Melanie Bright, “Does Parliamentary Oversight of Canadian Peacekeeping Work?” Vanguard, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1999, p. 5. An “order in council” is an order issued by the Governor in Council – that is, the Cabinet – either on the basis of authority delegated by legislation or by virtue of the prerogative powers of the Crown. It may deal, among other matters, with the administration of the government, appointments to office or the disallowance or reservation of legislation. (8) R.S.C. 1985, c. N-5. Section 31(1) of the National Defence Act enables the Governor in Council to place the Canadian Forces, or any element thereof, on active service whenever “it appears advisable to do so” by reason of an emergency or for the defence of Canada, or “in consequence of any action taken by Canada under the United Nations Charter, the North Atlantic Treaty or any other similar instrument for collective defence that may be entered into by Canada.” For further history and analysis, see Michel Rossignol, International Conflicts: Parliament, the National Defence Act, and the Decision to Participate, Background Paper BP-303, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, August 1992, p. 14-21. (9) Active service status is not a prerequisite to the deployment of military forces within or outside of Canada, or to the liability of Canadian Forces members to serve. Active service status does, however, have implications for soldiers in terms of: coverage for benefits under the Canadian Forces Superannuation Act; the timing of release from the forces; the application of the Code of Service Discipline to reserve members in certain circumstances; and the applicability or aggravation of certain military offences. (10) SSCFA, p. 71-72. (11) Michel Rossignol, International Conflicts: Parliament, the National Defence Act, and the Decision to Participate, Background Paper BP-303, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, August 1992, p. 18-19. (12) SSCFA, p. 70. Also see p. 74 for more information about the practice in the United States and Denmark. (13) Kim Richard Nossal (Department of Political Science, McMaster University), “‘Parliament will decide’ revisited: legislative involvement in the deployment of Canadian Forces overseas,” Brief to the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, Ottawa, 8 June 1999, p. 2. (14) Melanie Bright, “Does Parliamentary Oversight of Canadian Peacekeeping Work?” Vanguard, Vol. 4, No. 4, (1999), p. 5. (15) Hon. Arthur C. Eggleton, Minister of National Defence, Letter to a Member of Parliament about Parliament’s role in the deployment of the Canadian Forces, 7 April 2000, p. 3. (16) Nossal (1999), p. 5. (17) Ibid. (18) Bright (1999), p. 6. (19) Nossal (1999), p. 5. (20) Ibid., p. 2. (21) Rossignol (1992), p. 3-4. (22) SSCFA, p. 74. (23) Bright (1999), p. 5. (24) House of Commons, Journals, 7 December 1994 and 19 June 1995. (25) House of Commons, Journals Index, 35-2, p. 137. (26) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 10 June 1998 at 1825. (27) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 19 April 1999 at 1205. (28) SSCFA, p. 76. (29) SSCFA, p. 77, Recommendation 13. (30) SSCFA, p. 72 and 75. (31) Kim Richard Nossal (Individual Presentation), Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Evidence, Issue 41, 8 June 1999, p. 22. (32) SSCFA, p. 75. (33) Bright (1999), p. 5. (34) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 10 June 1998 at 1825. (35) SSCFA, p. 77, Recommendation 15. (36) Douglas L. Bland, Parliament, Defence Policy and the Canadian Armed Forces, The Claxton Papers, No.1, September 1999, p. 3. (37) Bright (1999), p. 7. (38) Nossal (1999), p. 6. (39) Bright (1999), p. 7. (40) Much of the information in this section, as it deals with the Persian Gulf War, the Korean War, and the First and Second World Wars, is taken from Rossignol, (1992). (41) Nossal (1999), p. 3. (42) Nossal (1999), p. 3 and Rossignol (1992), p. 2. (43) Nossal (1999), p. 3. (44) SSCFA, p. 72. (45) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1 February 1923, p. 33. (46) Nossal (1999), p. 3. (47) Rossignol (1992), p. 3-4. (48) Ibid., p. 5-6. (49) Ibid., p. 8. (50) Nossal (1999), p. 3. (51) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 30 June 1950, p. 4459. (52) Rossignol (1992), p. 8-9. (53) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 8 September 1950, p. 495. (54) Rossignol (1992), p. 9-10. (55) Ibid., p. 13. (56) Canada, House of Commons, Journals, 23 October 1990, p. 2157. (57) Canada, House of Commons, Journals, 29 November 1990, p. 2320-2323. (58) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 15 January 1991, p. 16984. (59) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 15 January 1991, p. 16995 and 17130-17131. (60) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 22 January 1991, p. 17568. (61) Rossignol (1992), p. 22. (62) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 4 December 1992, p. 14652. (63) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 December 1992, p. 14727. (64) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 December 1992, p. 14728. (65) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 December 1992, p. 14737. (66) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 December 1992, p. 14799. (67) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 30 September 1998, p. 8583. (68) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 October 1998, p. 8914. (69) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 7 October 1998, p. 8917. (70) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 12 April 1999, p. 13596. (71) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 17 February 1999, p. 12038. The House also noted, at the same time, “possible changes in peacekeeping activities in the Central African Republic.” (72) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 24 March 1999, p. 13433. (73) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 24 March 1999, p. 13442-13444. (74) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 12 April 1999, p. 13573. (75) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 12 April 1999, p. 13596. (76) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 19 April 1999, p. 14018. (77) Hon. Arthur C. Eggleton, Minister of National Defence, Letter to a Member of Parliament about Parliament’s role in the deployment of the Canadian Forces, 7 April 2000, p. 1. (78) SSCFA, p. 73. (79) Nossal (1999), p. 4. (80) Ibid., p. 4. (81) Ibid., p. 4. (82) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 13 March 1964, p. 911. (83) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 13 March 1964, p. 917. (84) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 13 March 1964, p. 926. (85) Nossal (1999), p. 4. (86) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 4 January 1973, p. 7. (87) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 5 January 1973, p. 29. (88) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 16 January 1973, p . 328. (89) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 24 January 1973, p. 596. (90) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 24 January 1973, p. 603-604. (91) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1 February 1973, p. 862-892. The motion appears on p. 863. (92) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1 February 1973, p. 863. (93) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1 February 1973, p. 885. (94) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1 February 1973, p. 890. (95) For examples, see ibid., as well as 7 February 1973, p. 1034. (96) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 5 March 1973, p. 1866. See also 27 March 1973, p. 2639-2640. (97) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 5 March 1973, p. 1881. See also 9 March 1973, p. 2063-2064, 20 March 1973, p. 2386 and 27 March 1973, p. 2639-2640. (98) In both instances, the government maintained its right to present its decision to Parliament. (99) Nossal (1999), p. 4. (100) Ibid., p. 5. (101) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 25 January 1994, p. 263. (102) Ibid. (103) Ibid. (104) Ibid. (105) Ibid., p. 265. (106) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 21 April 1994, p. 3348. (107) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 21 September 1994, p. 5952. (108) Ibid., for example, at p. 5960. (109) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 29 March 1995, p. 11225. (110) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 28 March 1995, p. 11142. (111) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 4 December 1995, p. 17115. (112) Nossal (1999), p. 5. (113) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 28 April 1998, p. 6254. (114) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 9 February 1998, p. 3548 and 10 June 1998, p. 7961. (115) Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 28 February 1996, p. 71. |