A CLOSER LOOK AT THE FLAT TAX

Prepared by:

Marc-André Pigeon

Economics Division

23 August 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE FLAT TAX IN OTHER COUNTRIES

KEY FEATURES OF THE CURRENT TAX SYSTEM

THE BUDGETARY CONSEQUENCES OF A FLAT TAX

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE FLAT TAX

The ultimate in flat tax reforms would create a single and simple system comprised of two basic ingredients:

a single marginal tax rate that would apply to businesses and individuals alike, effectively replacing the entire tax code, including all of its deductions and credits; and

a large basic exemption so that the flat tax is not unfair to low-income families and individuals.

Flat tax advocates argue that these changes would not only lead to a simpler tax system, but also improve economic efficiency, which means there would be fewer impediments to businesses making decisions for purely economic reasons and individuals making decisions based purely on their preferences. Most real-life flat tax proposals fall short of these goals, imposing a uniform marginal tax rate while retaining many – and, in some cases, all – of the deductions, credits and tax breaks in the existing system. Hybrid flat tax proposals have been surfacing and resurfacing in the United States since at least the early 1980s. In this country, the Canadian Alliance has done much to bring the issue to the fore, recently proposing its own flat tax but subsequently shelving the idea – at least temporarily.(1) Nevertheless, if the United States is any guide, the issue is likely to re-appear in the policy arena, especially given the ever-changing and increasingly complex nature of the taxation system and the strong forces promoting international harmonization of taxes and regulations.

This paper has three objectives:

To provide some much-lacking historical and international perspective on the issue. Just how old is the flat tax idea? Where did it come from? And has it been tried before and where?

To look at the theoretical and practical arguments for and against a flat tax. Why do some people support a flat tax while others oppose it?

To determine the cost of a realistic flat tax plan in Canada, given reasonable assumptions.

Before answering these questions, it is useful to briefly review two key concepts of tax equity from the theory of public finance.

Horizontal equity means that equal persons should be treated equally in the tax code. Although no two people are ever perfectly equal, the term usually applies to two people or families with roughly the same income and social circumstances.

Vertical equity, the flip-side of horizontal equity, means that people should be taxed differently based on their ability to pay. For example, a family earning $60,000 with no children is able to pay more in taxes than a family earning $60,000 with four children, assuming all else is equal.(2)

Other terms – including progressive, proportional and regressive tax regimes – need to be defined because they turn up frequently in popular discussions and can easily be abused or confused. Most economists define a progressive tax regime as one where those with lower income pay a smaller share of their total income in taxes than those with higher income. A regressive taxation regime is just the opposite: lower-income persons or families pay a greater share of their income in taxes than do higher-income persons or families. A proportional tax regime is one where the same marginal tax rate applies to all persons, regardless of income, so that everyone pays the same proportion of their income in taxes.

In the extreme, a regressive tax would mean that low-income earners would pay a higher tax rate than high-income earners. Regressive taxes, however, are often a lot more commonplace than is generally thought to be the case. Taxes on food, for example, are “the same” for everyone and yet are considered regressive because food purchases account for a bigger portion of total income for a typical low-income individual or family than they do for their high-income counterparts. The following table helps to illustrate the differences between each type of tax.

Table 1: Comparing Different Tax Régimes

Progressive (on all income) |

Proportional (on all income) |

Regressive (sales tax on food) |

|

| Family A – Upper Income | |||

| Income | $150,000 |

$150,000 |

$150,000 |

| Amount subject to taxes | $150,000 |

$150,000 |

$10,000 |

| Rate at which income is taxed | 26% |

17% |

6% |

| Tax paid | $39,000 |

$25,500 |

$600 |

| Percentage of income | 26% |

17% |

0.4% |

| After-tax income | $111,000 |

$124,500 |

$149,400 |

| Family B – Lower Income | |||

| Income | $40,000 |

$40,000 |

$40,000 |

| Amount subject to taxes | $40,000 |

$40,000 |

$10,000 |

| Rate at which income is taxed | 22% |

17% |

6% |

| Tax paid | $8,800 |

$6,800 |

$600 |

| Percentage of income | 22% |

17% |

1.5% |

| After-tax income | $31,200 |

$33,200 |

$39,400 |

In the popular debate, there is also much confusion about whether a flat tax, which is proportional in a strict definitional sense, can be effectively progressive, i.e., can it assure that a low-income family or individual pays less of its total income in taxes than does a high-income family or individual? Given a sufficiently large basic tax exemption, the answer is an unambiguous yes.(3) To see why, consider the table below, where we assume two families (the Smiths and Simpsons, each with a sole breadwinner) and compare a progressive tax regime with a proportional tax regime.

Table 2: Comparing Progressivity

A two-rate progressive tax regime |

A flat tax with |

A flat tax with |

|

| The Smith Family – Upper Income | |||

| Income | $150,000 |

$150,000 |

$150,000 |

| Exempted income | $10,000 |

$20,000 |

$0 |

| Taxable income | $140,000 |

$130,000 |

$150,000 |

| Marginal tax rate(s) | 17% and 25% |

17% |

17% |

| Tax paid | $27,000 |

$22,100 |

$25,500 |

| Effective marginal tax rate | 18.0% |

14.7% |

17.0% |

| Tax saving relative to a progressive regime | n/a |

$4,900 |

$1,500 |

| The Simpson Family – Lower Income | |||

| Income | $40,000 |

$40,000 |

$40,000 |

| Exempted income | $10,000 |

$20,000 |

$0 |

| Taxable income | $30,000 |

$20,000 |

$40,000 |

| Marginal tax rate | 17% |

17% |

17% |

| Tax paid | $5,100 |

$3,400 |

$6,800 |

| Effective marginal tax rate | 12.8% |

8.5% |

17.0% |

| Tax saving relative to a progressive regime | n/a |

$1,700 |

-$1,700 |

The first column shows a hypothetical graduated or progressive tax system (with a $10,000 basic exemption) that imposes a marginal tax rate of 17% on the first $100,000 of income and 25% for income above that threshold. Because the Smith family’s income exceeds $100,000, the Smiths pay both tax rates for a total tax bill of $27,000, or 18% of its income. The Simpsons, on the other hand, pay only $5,100 or 12.8% of their income. This system is progressive on two counts. First, in the “formally progressive” sense defined by William Vickrey, namely because it imposes different marginal tax rates for different income levels (17% and 25%) and second, because the average tax rate (calculated after factoring in basic exemptions) is lower for low-income families. The fact that the Smiths pay more in dollar terms than the Simpsons says little about whether the system is truly progressive, at least given the way most economists have defined the term. The Smiths would pay more than the Simpsons even under an extremely regressive (and improbable) tax system that imposed a 4% tax rate on all the income of high-income families, but a 17% tax rate on all the income of low-income families. In this extreme case, the Smiths would pay $5,600 versus $5,100 paid by the Simpsons.

Now suppose there’s a sudden switch to a flat tax system. The second column shows how a flat or proportional tax – given a large enough basic exemption (for illustrative purposes, the exemption has been increased to $20,000 from $10,000 in the progressive regime) – can be at least as progressive as, if not more progressive than, a “formally” progressive tax.(4) Under this scheme, the Smith family’s effective tax rate falls to 14.7% and it saves a net $4,900 relative to the progressive regime, while the Simpson family’s effective tax rate falls to 8.5% and it saves a net $1,700 relative to the progressive tax system. Again, it must be stressed that just because the Smiths save more than the Simpsons under this flat tax proposal does not mean the system is regressive. The Smiths still pay a greater portion of their total income in taxes than do the Simpsons. It would be hard to avoid this outcome (i.e., a greater absolute tax saving for the high-income family) given any meaningful reduction in marginal tax rates. Generally speaking, the most effective way to give more to lower-income families without an even bigger saving for the wealthy is to have targeted deductions and exemptions.

Finally, column three shows what could be called a “doubly” pure flat tax because it has no basic deduction. Under this system, the Simpsons are unambiguously worse off than under the progressive system or the proportional system with large exemptions. Meanwhile, the Smiths still fare better than they do under the progressive system but not quite as well as under the flat tax with a large basic deduction. This analysis illustrates two key points:

First, a flat tax can be made effectively progressive with large basic exemptions or some combination of exemptions and deductions.

Second, people concerned with getting more dollars to low-income persons relative to high-income persons in absolute terms should focus their attention on targeted (rather than universal, which is implied in marginal tax reductions) tax breaks such as tax credits and/or welfare transfers.

The term “flat tax,” at least insofar as it has gained widespread currency, has been around since 1981, when the idea was put into the policy arena by Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka. These two Stanford academics published a book entitled The Flat Tax containing the essential features of their proposal which can be summed up in five points.

First, reduce corporate and personal taxes to 19%.

Second, replace targeted depreciation schedules with a single, first-year, write-off provision so that firms are taxed on their cash flow.

Third, eliminate all extraneous business and personal tax deductions and tax credits that get in the way of establishing a true “consumption-based” tax, i.e., people are taxed only on what they spend or take out of the economy. For firms, this means taxes would be calculated on net profits or, in other words, total revenue minus total costs (inputs, wages/salaries and new equipment). For individuals, this means taxes would be calculated on total wage, salary and pension income less a basic exemption (see below).

Fourth, eliminate double taxation of dividends (already partially accomplished in Canada) and capital gains. Individuals would no longer pay any tax whatsoever on dividend income or capital gains. The rationale is straightforward: because dividends are paid out of net after-tax profits, there is no reason to tax them again in the hands of shareholders. The rationale for exempting capital gains (at the individual level) is similar, and this is discussed more fully later in the paper.

Fifth, create large basic exemptions so the tax system is progressive.

Hall and Rabushka argue their plan would not only lead to a simpler tax system – tax forms for most citizens and businesses would be half a page long, at most – but also promote efficiency and hence economic growth in the long run. The current system, they argue, is too complex and poorly designed, leading to unanticipated and negative consequences. For example, U.S. employers are increasingly paying their employees in “fringe benefits” in lieu of wages or salary because they can deduct these benefits as expenses. At the same time, employees receive the benefits tax-free. A flat tax system would treat these kinds of compensation equally and lead to higher pay for employees who would then have more freedom to make decisions in their own best interest (about, for example, life insurance) rather than have them imposed by an employer whose motivation may be purely tax-driven. The economy, as a whole, would consequently enjoy efficiency gains.

Similarly, Hall and Rabushka argue their one-year write-off provision would increase investment because firms would have a strong incentive to add to their physical capital (machines, buildings, factories) because of the tax savings. The two academics also argue that investment would increase because their flat tax proposal is a true consumption tax. To the extent the economy is constrained by an inadequate supply of savings, a flat tax would improve the economy’s growth prospects by encouraging saving, which would lower interest rates and make investment in physical capital more attractive.

By the mid-1990s, at least eight flat tax proposals – most of them hybrids of the Hall-Rabushka proposal and the existing tax system – were on the table in the United States. Many of these had been put forward by Republican presidential candidates but some also came from Democratic representatives (Banks, 1996). The bipartisan nature of these proposals speaks to the fact that a flat tax has the potential of being fair to low-income families and individuals provided it features some kind of large minimum deduction. Most of the proposals followed the Hall and Rabushka plan in spirit but did not eliminate key deductions, one of the most important being the deductibility of interest payments on home mortgages, so cherished by Americans; the construction industry lobby had a strong interest in retaining this feature of the tax code. The end result was that most flat tax proposals were not revenue-neutral: absent draconian spending cuts, they would have implied increased deficits, something that was not politically palatable in the mid-1990s.

However, the idea of a flat tax on income – minus the name “flat tax” – dates much further back than the 1980s. In fact, the idea of taxing all personal and business income at the same rate is as old as the income tax itself, at least in the United States. In the late 19th century, for example, proponents of a U.S. proportionate (i.e., flat by another name) tax saw it mainly as a means of redressing regressive tariff and excise taxes, which at the time accounted for the bulk of government revenue.(5) In the context of that era, any kind of income tax, including a flat tax, was seen as a “fair” means of attenuating the dramatic rise in inequality that accompanied rapid technological change and industrialization in the late 19th century.(6)

In Canada, the federal government began taxing personal income in 1917 to pay for the large expenses incurred for the war effort.(7) Until that point, “Ministers of Finance had contrived almost annually in their budget speeches, by the use of most inadequate statistics, to prove to their own satisfaction that Canada was one of the lowest taxed countries in the world” (Perry, 1955, p. 144).(8) Although initially seen as only a temporary measure to meet pressing needs, income taxes quickly became a fixture of government fundraising, especially with the twin crises of the Great Depression and the Second World War, both of which helped consolidate the federal government’s jurisdiction in this area.(9)

From the beginning, Canada’s income tax system was progressive, perhaps due to the fact that many were concerned about war profiteering by industrialists. Although all income was taxed at a so-called “normal” rate of 4%, “graduated surtaxes” of 2% (on income of $6,000) to 25% (on income of $100,000 or more) were imposed once certain income thresholds were crossed. The tax system also included basic personal exemptions of $3,000 for married persons and $1,500 for single persons on the normal tax rate (and not the surtaxes), which added another heavy layer of progressivity to the tax system. One estimate suggests that the original income tax system affected at most 1% of the total population.(10)

The original Income War Tax Act was a simple document, taking up all of ten pages. It was little changed until 1962, when the Carter Commission recommended a more comprehensive tax base. After a series of public hearings and a White Paper on Tax Reform, new legislation was introduced in 1972 that modernized the tax act, effectively repealing and replacing virtually all of the old tax laws and forming the backbone of Canada’s current system.(11)

THE FLAT TAX IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Despite the superficial intuitive appeal of the idea and the high-profile nature of the U.S. debate, the flat tax has been adopted by only a handful of countries. The most widely cited historical example is Hong Kong, which imposes a maximum tax rate of 15%.(12) Business groups have cited the country’s flat-tax system as an important part of the Hong Kong economy. There are, however, many other factors that contributed to Hong Kong’s strong growth. In fact, it seems unlikely that the flat tax alone or even in large part explains Hong Kong’s success because other economies with much different tax structures but similar cultural and geographic characteristics (Japan, for example) have had similar trade records.

The so-called “transition economies” (i.e., former Eastern Bloc countries) seem to be the most willing to experiment with the flat tax idea. Estonia established a flat tax in 1994 and Latvia followed suit in 1995. In August 2000, Russia adopted a 13% flat tax on income in an effort to meet its revenue needs. Under Russia’s old tax system, which imposed a graduated tax rate ranging from 12% to 30%, taxation revenue consistently fell short of the government’s objective because of tax evasion coupled with the government’s inability to enforce its tax laws. Again, it is too early to say – and, to our knowledge, no study has shown – whether the flat tax had a positive effect on Russia’s economic growth or government revenue.

The appeal of the flat tax to the transition economies makes some intuitive sense given the historical record. As discussed earlier, the idea of a flat tax first came onto the scene at about the same time as income taxes and that is, arguably, when it had its best chance of being implemented.(13) To the extent that the transition economies are relatively new to capitalism and are “starting from scratch,” there are far fewer obstacles to imposing a flat tax system. Indeed, many flat-tax proponents in the U.S. and Canada acknowledge that the biggest political obstacle to their plan is the fact that the current tax system is entrenched both at the institutional and personal level, where many persons either make a living off the complexity of the system (tax lawyers and accountants, for example) or are subsidized through the tax system (the construction industry in the United States, for example).

KEY FEATURES OF THE CURRENT TAX SYSTEM

The “core” of Canada’s current tax code has remained remarkably unchanged since 1988. From 1988 through to the beginning of 2001, there were three marginal tax rates of 17%, 26% and 29%.(14) Both the tax rates and the tax thresholds (the levels) were little changed throughout,(15) adding an element of regressivity to an otherwise progressive tax system: individuals whose income rose in line with inflation below 3% often found themselves in a higher tax bracket even though their “real” situation in terms of income (i.e., after inflation but before taxes) had not changed.(16) Almost by default then, the 2000 budget represents some of the most radical changes to the income tax system since 1988.

First, it restored full indexation for all tax thresholds as well as the basic exemption.

Second, it laid out a plan to reduce marginal tax rates, starting with a cut in the middle rate to 25% beginning 1 July 2000.

Third, it increased the tax thresholds at which the marginal rates apply. The lowest rate applied to the first $30,004, the middle for the next $30,004, and the top rate to income above $60,008.

Fourth, it reduced the capital gains inclusion rate to 66.6% from 75%.(17)

Since then, the government has introduced further tax cuts. Beginning in January of 2001, the lowest tax rate fell to 16%, the middle rate was cut to 22%, and income between $60,000 and $100,000 now faces a 26% marginal tax rate instead of 29%. Income in excess of $100,000 will still be taxed at 29%. The capital gains inclusion rate was further reduced to 50%, and the plan to cut all corporate tax rates to 21% (service-sector and high-technology firms generally face higher tax rates – the 2000 Budget dropped the tax rate for these firms to 27%) was accelerated.

As with most policy proposals, the flat tax proposal(18) has its advocates and opponents. From a political perspective, flat-tax advocates usually argue a flat tax has three key “selling points.” They are:

Simplicity: a true flat tax plan would eliminate frustrating and wasted hours spent trying to cope with extremely complex laws and would, consequently, reduce and maybe even eliminate the need for tax planners, tax consultants and tax lawyers.

Equity: The plan is at least as, if not more, horizontally equitable than the current tax system which, for example, sometimes discriminates against single-person households. For example, a family with a combined income of $60,000 (assuming each spouse makes $30,000) will pay less tax under a graduated tax system than a single person earning the same income. Vertical equity (progressivity) can also be assured given large enough exemptions.

Revenue Neutrality: The plan can be revenue-neutral for two reasons. First, the lower and more straightforward tax rate means there’s likely to be less tax evasion. Second, by design, a pure flat tax should tax a larger base, albeit at a lower rate. In other words, a broader “swath” of income is taxed than under the current system, compensating for the lower tax rate.

There are a number of less tangible economic arguments in favour of a flat tax, most of which hinge on efficiency considerations. They include:

Fewer economic distortions: The current tax system may encourage all kinds of behaviour that makes little or no economic sense, including:

– Payment through “benefits” in lieu of wages/salary (discussed earlier). Again, this is inefficient to the extent that what the corporation chooses for its employees does not match what they would have chosen if they had been compensated with higher salaries.

– Double taxation of savings. Dividend income under a flat tax proposal would only be taxed once. Similarly, capital gains income would be taxed only once at the corporate levels and no longer at the personal level.(19) Thus, corporations would make their financing decisions (i.e., to borrow, sell shares or float bonds) independent of the tax structure.

– Labour market distortions. Under the graduated tax system, some employees may be reluctant to take a higher-paying job if it means paying more taxes. To the extent that this happens, the current system reduces efficiency: society as a whole would benefit from that person working to his/her potential.

More accurate prices: The flat tax would mean that tax considerations would no longer have such a distortionary impact on prices. Decisions would be made for purely economic reasons or on the basis of individual preferences, relatively unimpeded by tax considerations. Prices should therefore more accurately reflect true supply and demand conditions.

Increased savings and investment: By taxing income only once, a flat tax should lead to increased savings which, in turn, theory suggests could lead to lower interest rates and more investment. The one-year write-off provision also holds out the promise of more investment.

Faster growth and higher productivity: All things being equal, a flat tax would lead to more investment which should improve productivity and lead to stronger economic growth. This in turn could have feedback effects on the federal government’s budgetary position.

Increased transparency: A flat tax would mean that all tax increases (and decreases) would be extremely visible and clear, unlike under the current system. For proponents of the flat tax who favour smaller government, this could be a strong selling point because all tax increases to finance more government spending would probably entail a large “political cost.”

There are, of course, a number of arguments against a flat tax. Flat tax opponents usually make two “visible” or popular arguments against the tax:

A flat tax violates the common notion of fairness which differs from economists’ vision of the concept.(20) Although it’s true that a flat tax can be progressive, it is also true that moving to a flat tax means that higher-income families receive the bulk of the benefit of a given tax cut in absolute terms. As noted earlier, this is to some extent inevitable because even a small percentage reduction in tax rates for very high-income families translates into a large absolute tax saving. Nevertheless, giving “more” in absolute terms to the wealthy seems to violate popular notions of fairness. The popular sense of fairness also seems to be transgressed by the image of a wealthy person living off of his/her savings (either through capital gains or dividend/interest payments) without personally paying any income tax,(21) especially if he/she inherited the money or earned it through luck rather than hard work.

Flat-tax proponents exaggerate the benefits of their proposal.

– Most people already have very simple tax returns. In the United States, for example, citizens can file simplified tax forms that are only a page long. The benefit of “simplifying” the tax code, therefore, really only accrues to the well-off.

– Flat tax plans are unlikely to be revenue-neutral because by design they aim to reduce the top marginal rate while providing large basic exemptions for low-income earners. This “you-can’t-have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too” argument says that a larger tax base won’t be enough to make up for the lost revenue and nor will the promised economic growth, improved efficiency and greater tax compliance. Assuming this non-neutrality then, a flat tax would likely mean reduced spending on social programs, including those targeted to low-income persons. Thus, although low-income persons may pay less in taxes (and, indeed, receive larger tax rebates), they may lose at least as much from reduced transfer payments.

There are also a number of economic arguments against the flat tax:

A flat tax may attenuate the counter-cyclical effects of the current system. For example, during an expansion, government revenue tends to rise quickly under a formally progressive tax system, essentially “dampening” some of the excesses of the cycle. The reverse occurs during a downturn. Although no one is sure of the dynamics of a flat tax under a business cycle, it seems at least plausible to suggest that the dampening effects wouldn’t be as great. For example, investment tends to move pro-cyclically, i.e., it increases as the economy nears its peak and falls as it hits a trough. All things being equal, the one-time depreciation part of the Hall and Rabushka flat tax proposal would effectively reduce government revenue (relative to the existing system) at the peak and increase it in the trough, accentuating the cyclical highs and lows. This could imply more acute economic ups and downs.

Although popular notions of fairness may not accord with economists’ vision of the concept, they should not be dismissed out of hand. As former Canadian Economics Association President Lars Osberg suggested in an article on trends towards worsening inequality in Canada,(22) civil society (volunteerism, the willingness to pay taxes, abide by laws, help out) is perhaps more fragile than commonly thought. As Russia and other lesser-developed countries show, there is a very real danger that the fabric of civil society can be destroyed when policy-makers impose abrupt changes to the institutional structure, of which the tax system is an important part. Also, a flat tax inevitably implies a greater tax cut in absolute terms for high-income individuals/families and the wealthy; this could mean a worsening of inequality, especially if the flat tax is not revenue-neutral and social programs are consequently cut. Even if the tax is revenue-neutral, a flat tax could mean worsening inequality in the long run if only because high-income earners and the wealthy are generally better able to invest their tax savings and make them grow more quickly than are low-income persons.

A flat tax has ambiguous labour market effects. Although most economists agree that a flat tax would have a positive substitution effect (i.e., people would want to work more knowing their income would be taxed at a lower rate), the income effect is less clear: because they get to keep a greater share of their income, some workers may choose to work less because they can still achieve the same level of consumption as before the tax cut. There is no a priori way of knowing which effect will dominate or even if these two effects are the relevant ones; sociological factors may dominate. Some arguments in favour of a flat tax are open about this ambiguity. For example, the case is frequently made that the current system discriminates against single-income two-parent households, suggesting that there is an incentive for both partners to work at lower wages than would be the case under a fairer system. Doing away with these incentives via a flat tax could, perversely, reduce labour force participation.(23)

The lack of taxation on capital gains could worsen income inequality (and violate the popular perception of fairness) to the extent that the market does not, in fact, perfectly “price-in” future earnings. Put another way, if markets are prone to herd-like behaviour, as the recent collapse of the “dot.com” craze suggests and as some research into the psychology of investors indicates, then some investors may sometimes earn large capital gains with no “real” underpinning, that is, they obtain money for nothing (often, companies whose shares soar end up going broke – the Canadian mining firm of Bre-X being a classic example). This is a perverse form of income redistribution not based on work effort but on gambling skills and luck.(24)

It could be argued that Canada already has a flat tax of sorts – for those whose income exceeds the top threshold (soon to be $100,000 but currently $60,008). This should, all things being equal, provide sufficient incentive to draw workers into the labour force. In other words, a formally progressive system with a flat tax at the top may perversely incite people to work harder, especially if their utility is augmented by the higher social standing that usually goes with more income.

THE BUDGETARY CONSEQUENCES OF A FLAT TAX

Up to now, the discussion in this paper has been rather abstract. This section attempts to present a real-world sense of the budgetary consequences of a flat tax that retains most of the current system of deductions and tax credits. It is important to stress this is very much unlike the Hall and Rabushka proposal that has been examined throughout most of this paper. The rationale for looking at this hybrid flat tax is simply that significant institutional changes are rarely implemented except in times of crisis. This task begins with a question: What is the lowest flat tax that could be imposed if all the features (tax cuts and spending initiatives) implemented in the most recent budget documents (Budget 2000 and the economic supplement) were retained and an assumption was made that future governments are committed to: a) maintaining at least a balanced budget; b) increasing nominal expenditure at the same rate as population growth plus inflation; and c) reducing the debt by at least $6 billion per year? This is clearly a difficult question given the complexity of the tax code. Fortunately, Statistics Canada has developed a model called the Social Policy Simulation Database (SPSD/M) that gives a sense of what a flat tax policy would cost given these conditions. Before looking at the results of this experiment, two important cautionary remarks are in order:

First, as with all models of this kind, one should heavily discount projections beyond a year or two for the simple reason that the assumptions girding the model are very quickly made obsolete by real-life events. The safest projections are the ones nearest in time.

Second, the SPSD/M model is “static” in that it does not allow for any kind of economic growth. All projected revenue increases arise out of nominal (inflationary) changes in measured output. This is important because flat tax proponents generally argue that their measures would stimulate economic growth through improved efficiency and possibly increased spending.(25)

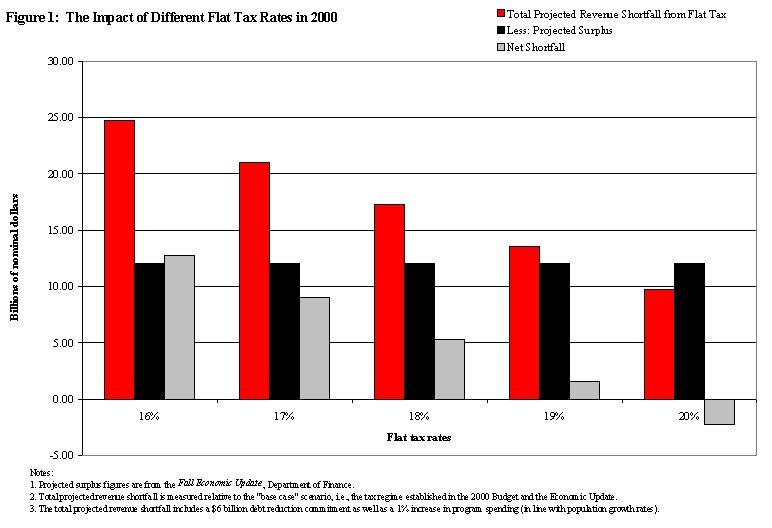

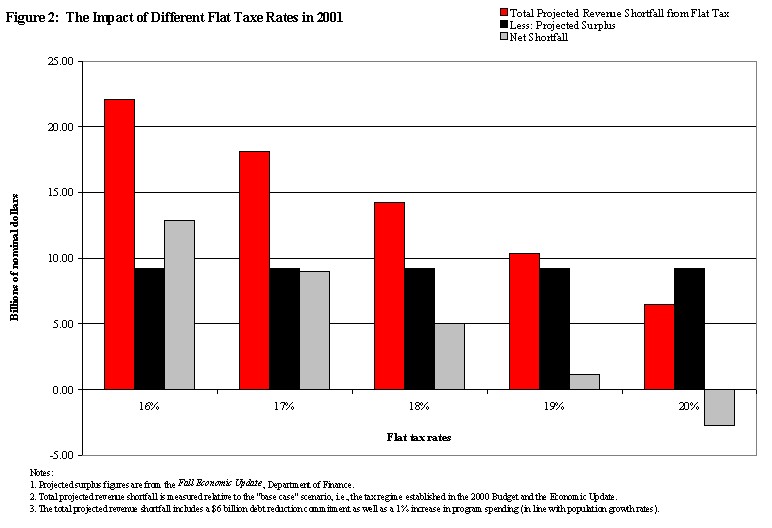

Figures 1 and 2 show results for the calendar years 2000 and 2001.(26) The charts show clearly that a revenue-neutral flat tax – given the proposed spending increases, debt reduction plans, and existing system of deductions and credits – would have to be somewhere between 19% and 20%. Again, it must be stressed that the figures in this paper were calculated relative to the base case, namely the tax system modified for changes in the 2000 budget as well as the fall economic statement. Note also that the total cost figures include the effects of putting in place a flat tax plus 1% annual spending increases (in line with population growth) and $6 billion in annual debt reduction debt.

The discussion in this paper has attempted to provide a relatively complete contextual picture of the flat tax by looking at its historical roots, its modern-day uses, and arguments for and against the idea. Some likely budgetary consequences of the tax, given the structure of a politically plausible proposal and the current tax system, have also been considered. These calculations should be viewed as merely suggestive. Much can happen in a year or two that would invalidate these figures, potentially making this kind of flat tax more or less feasible. If one conclusion were drawn from this analysis, it might be this: the historical and international record suggest that the odds of moving towards a flat tax increase greatly after an abrupt and dramatic failure of the existing tax system (Russia) or at the earliest stages of an income tax system (Estonia, Latvia and Hong Kong). Short of that, the sheer inertia behind the existing tax system invariably corrupts flat tax proposals beyond recognition, weakening or destroying most of the idea’s strongest selling points and ultimately cutting into the revenue-generating potential of the proposal. This in turn threatens core programs, and that may entail high political costs.

Alliance Party. 2000. “Solution 17.” Internet: http://www.canadianalliance.ca/index_e.cfm.

Beauchesne, Eric. 13 September 2000. “Canada Duplicating U.S. Economic Miracle.” The Ottawa Citizen, Internet edition: http://www.ottawacitizen.com/.

Canada. 1987. “The White Paper on Tax Reform: 1987.”

Canada. Department of Finance. 2000. “The Budget Plan 2000.” Department of Finance Distribution Centre.

Chernick, Howard and Andrew Reschovsky. September-October 2000. “Yes! Consumption Taxes are Regressive.” Challenge Magazine, pp. 60-91.

Gillespie, Irwin W. 1991. “Tax, Borrow & Spend: Financing Federal Spending in Canada: 1867-1990.” Ottawa: Carleton University Press Inc.

Hall, Robert E. and Alvin Rabushka. 1995. The Flat Tax. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press.

Lerner, S., C.M.A. Clark and W.R. Needham. 1999. “Basic Income: Economic Security for All Canadians.” Toronto: Between the Lines.

Moore, Stephen. 14 January 1997. “The Alternative Maximum Tax.” Editorial, Wall Street Journal.

Perry, David P. 1997. “Financing the Canadian Federation, 1867-1995: Setting the Stage for Change.” Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation.

Perry, J. Harvey. 1955. “Taxes, Tariffs and Subsidies.” Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Rosser, J. Barkley Jr. and Marina Vcherashnaya Rosser. 2001. “Inequality and Underground Economies.” Challenge Magazine, pp. 39-50.

Slemrod, Joel. 1996. “Deconstructing the Income Tax.” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, pp. 151-155.

Vickrey, William. 1987. “Progressive and Regressive Taxation.” In Eatwell, John, Murray Milgate and Peter Newman, eds. The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London: MacMillan Press.

(1) Flat tax proposals have also been made by Member of Parliament Dennis Mills. As well, the Progressive Conservative Party briefly considered the idea of a flat tax, as did the Reform Party, the predecessor of the Canadian Alliance.

(2) It is, of course, possible to imagine that the no-children family is burdened with large medical costs for one or both spouses or is looking after ill grandparents.

(3) See, for example, Nobel Prize winner William Vickrey’s definition of progressive and regressive taxation in the New Palgrave dictionary. What he calls “formally progressive” refers to the idea of different marginal tax rates applying to different income classes. However, he notes that even taxes and tax systems normally considered regressive can be “modified to reduce the degree of regressiveness or even render them moderately progressive.” An alternative way of achieving a progressive flat tax structure would be to tax all income (no exemptions) equally but combine that system with a large tax credit, essentially putting in place a negative tax or basic guaranteed income provision. See S. Lerner, C.M.A Clark and W.R. Needham’s “Basic Income: Economic Security for All Canadians” for one such proposal. Alternatively, a tax system with adequate exemptions and/or deductions – such as the Robert Hall and Alain Rabushka flat tax proposal and some of its variants – could achieve a similar blend of horizontal and vertical equity.

(4) This assumes that all else is equal, i.e., that the flat tax doesn’t somehow lead to cuts in social welfare programs that transfer money directly to lower-income families.

(5) This was true in Canada as well; see Perry (1997). Tariff and excise taxes were, and to the extent that they still exist are, regressive when they apply to goods and services that take up a greater share of the revenue of a low-income family or individual than of a wealthy family or individual because manufacturers are generally able to pass along the taxes in the form of higher prices. For example, excise taxes on gasoline are generally thought to be regressive because there is evidence that low-income families and individuals spend more of their total income on gasoline than do high-income families or individuals. However, as Gillespie (1991) shows, Canadian officials were historically reluctant to impose excise taxes on basic goods (coffee, tea, food) because of concerns about attracting and keeping immigrants who tended to spend significant portions of their income on these items. Most taxes were applied to so-called “sin” items such as alcohol. This was made politically feasible because of the forces promoting prohibition.

(6) The first, general income tax was enacted in Great Britain in 1799, to finance the Napoleonic War. The tax was subsequently repealed and re-introduced in the 1880s, when it was generally accepted as a permanent fixture of government finance.

(7) Income taxes were levied by some provinces before World War I.

(8) Perry argues there is reason to doubt those who claimed that pre-war Canada was a “tax haven,” citing work by Dr. O.D. Skelton showing Canada’s average per capita tax was $31.50, compared with $24.63 in England and $30.90 in the United States (p. 145).

(9) See David B. Perry’s “Financing the Canadian Federation, 1867-1995: Setting the Stage for Change,” Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1997.

(10) This historical overview is from Gillespie (1991).

(11) The CCH Canadian Ltd. summary of the income tax act – including all technical notes, pending amendments, Department of Finance Press Releases, and notices of ways and means – weighs in at about 1,890 pages.

(12) Hong Kong residents can choose between paying the flat 15% rate on income or the more traditional tax system, with its attendant deductions and exemptions. Some have proposed this kind of model, called a MAXTAX, for the United States. See Moore (1997) for a discussion of the MAXTAX proposal.

(13) The idea of a flat tax is intricately bound to that of the income tax, even when it exists in opposition to an income tax system (i.e., consumption taxes).

(14) Prior to 1988, there were ten marginal tax rates, ranging from 6% on the first $1,320 to 34% on taxable income exceeding $63,347.

(15) The tax thresholds in 1988 were $27,500 and $55,000 versus $29,590 and $59,180 at the beginning of 2000. That represents a 7.6% increase during a 12-year period compared with a 30% increase in the consumer price index over the same period.

(16) Although tax thresholds (brackets) were indexed to inflation above 3%, this meant little in practical terms because the Bank of Canada pursued an aggressive policy of keeping inflation below this threshold. It was successful for most of the decade.

(17) These were the short-term effects of the tax plan. The medium-term plan was to reduce the middle-income tax rate to 23% and increase tax thresholds to $35,000 for the lowest marginal rate and $35,000 to $70,000 for the middle rate. These higher thresholds are the result of both a basic “bump up” in the threshold plus full indexation. Indexation also was projected to increase the basic personal exemption to $8,000 from $7,131 within five years. The plan also increased the Canada Child Tax Credit to $2,400 by 2004 and eliminated the 5% surtax for persons with incomes up to $85,000.

(18) The reference to “flat tax” here means the Hall and Rabushka proposal which appears to be the most thoroughgoing and most discussed of existing proposals.

(19) The rationale is similar to that of taxing dividends only once. Consider, for example, company shares, which in theory represent the capitalized current value of after-tax future earnings. A capital gain is recorded when the price of these shares rise based on expectations of increased future profits. These future profits will be taxed when, and if (markets are not, after all, omniscient), they occur. Because the goal is to tax all income only once, it makes no sense to tax them in the hands of the shareholder who realizes this capital gain.

(20) Recent research in the burgeoning field of economics and psychology suggests that common notions of fairness are severely at odds with the economist’s vision of fairness.

(21) This income is, however, taxed at the source (i.e., at the corporate level).

(22) Lars

Osberg, “Poverty in Canada and the USA: Measurement, Trends and

Implications,” Presidential address to the Canadian Economics Association, Vancouver,

3 June 2000. Available online at

http://is.dal.ca/~osberg/uploads/Povtrend.PDF.

(23) This is seen as a selling point by some flat tax advocates who want to encourage stay-at-home mothers or fathers.

(24) Inequality may have direct economic impacts as well. For example, J. Barkley Rosser and Marina Vcherashnaya Rosser (2001) present empirical evidence that suggests heightened inequality may encourage the growth of black markets that erode the government’s revenue base.

(25) Some economists argue the principle that benefits would come from efficiency gains because the tax effects are nil in the long term.

(26) Note that these are calendar year figures while budgetary projections are generally done in fiscal years ending 31 March. To compensate for this discrepancy, the paper’s analysis has assumed that one-quarter of the surplus for 1999-2000 and three-quarters of the projected surplus for 2000-2001 represented the equivalent “calendar year” surplus for 2000. This yielded a projected surplus of $12 billion for calendar year 2000 instead of $11.9 billion for 2000-2001 and $9.2 billion for calendar year 2001 instead of $8.3 billion for 2001-2002.