CIR 79-16E

AID TO DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Prepared by:

Gerald Schmitz

Marcus Pistor

Megan Furi

Political and Social Affairs Division

Revised 2 May 2003

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Brief History: The Rise and Fall of Aid Fortunes

B. Composition of the Aid Budget

C. Program Structure

1. Bilateral Aid

(Geographic Programs)

2. Multilateral Aid

3. Canadian Partnerships

(Voluntary Sector Support, Education and Business Co-operation)

4. Other ODA Channels

a. Department

of Finance

b. Department

of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT)

c. International

Development Research Centre (IDRC)

d. The International

Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (ICHRDD)

e. The International

Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

f. Provincial

Governments

A. Linking Aid and Human

Rights

B. Reforming Aid

AID TO DEVELOPING COUNTRIES*

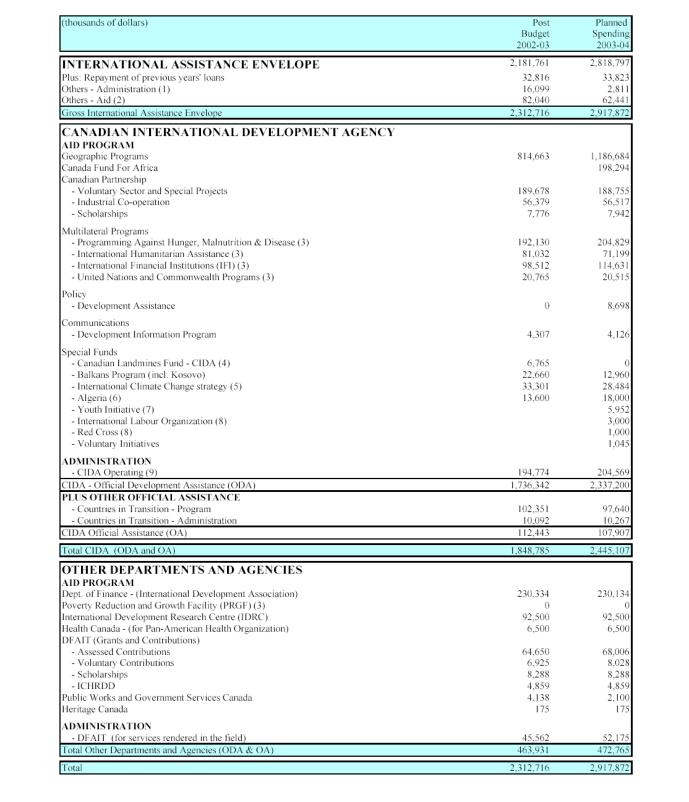

Canada will devote about $2.92 billion to international assistance in fiscal year 2003-2004, a significant increase over the $2.31 billion originally committed in the December 2001 Budget for 2002-2003, and up 8% from the actual 2002-2003 figure (which included $353 million added to the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) in the February 2003 budget). The IAE, which was created in 1991 to incorporate assistance to the post-communist “countries in transition,” is made up of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to developing countries (96% of the IAE) and Official Assistance (OA) to eastern European countries (4% of the IAE). The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) accounts for about $2.45 billion of this total, with contributions from other departments and agencies making up the rest; see Table 1 for a complete breakdown. CIDA is responsible for delivering both the ODA program and (since 1995) the OA program.

Canada reports its foreign aid expenditures to the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and is subject to an evaluation every three years. The Canadian ODA program was peer reviewed by the DAC in 2002. In its 1998 Peer Review, DAC had been critical of the steep cuts made to Canada’s aid budget in the 1990s and had raised concerns about their impact on Canada’s ability to meet international expectations of its being a leader in international co-operation. In the 2002 review, DAC noted that “an impressive series of major funding and policy decisions,” including the adoption of the DAC Recommendation on the Untying of ODA to Least Developed Countries (LDCs), showed an effort to address this concern. The review noted that “Canada’s development co-operation thus has strong new wind in its sails,” but cautioned that the political leadership must continue as Canada confronts future challenges.

In terms of planned program expenditures for 2003-2004, some observable changes from the preceding fiscal year include: an increase of approximately $372 million in CIDA’s geographic programs spending; an increase of about $16 million in funding for International Financial Institutions (IFIs); a small decrease ($250,000) in funding for UN and Commonwealth programs; a decrease of over 40% in funding for Balkans programs; and a small decrease in funding for the International Climate Change Strategy.

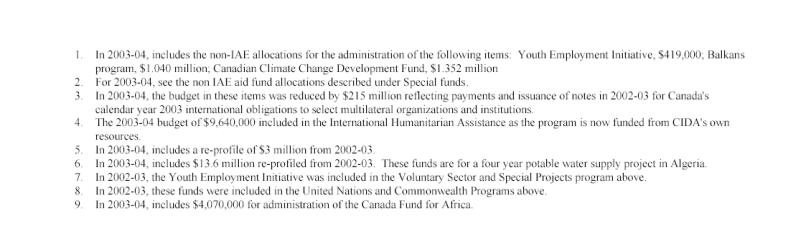

In addition to direct bilateral and multilateral assistance to other governments, ODA supports work on many small projects carried out by the Canadian voluntary sector, by international non‑governmental organizations (NGOs), and by private-sector partners in more than 100 countries. ODA consists of either grants or loans on highly concessional terms. Since 1986, all Canadian aid has been in grant form. CIDA’s spending constitutes about 84% of the IAE. The primary channel of delivery within CIDA is the geographic programs sector, which in 2003-2004 will receive 40.7% of the IAE. About 16% of the IAE is disbursed through the Department of Finance (for the IFIs), the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), and other departments. See Chart 1 for current data on channels of delivery.

Canada’s ODA has never come close to the UN target of 0.7% of GNP but did reach 0.5% in 1986‑1987, when it was slightly more than 2% of federal government expenditure. Since growing at an annual average rate of 7.4% between 1985 and 1989, however, the aid program absorbed large successive cuts from projected levels during the 1990s. Global aid levels also fell to their lowest in several decades. Canada’s ODA/GNP ratio dropped below 0.3% and its ranking among 22 OECD donor countries fell from 6th in 1995 to 17th in 2000. At the same time, additional demands on aid resources, including for emergency humanitarian relief, put further pressure on budgets for long-term development and poverty reduction.

In the past two years, this situation has begun to change. The December 2001 Budget indicated a commitment to increase the aid envelope by $285 million in 2003‑2004, and also announced a $500-million trust fund for Africa. At the United Nations International Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey, Mexico, in March 2002, Prime Minister Chrétien pledged future increases in the ODA budget of 8% annually. The February 2003 Budget confirmed this commitment. The “Monterrey Consensus” document adopted at that conference also affirmed that: “Leaders will urge developed countries, that have not yet done so, to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.2 per cent to least developed countries. Recipient and donor countries, as well as international institutions, should strive to make ODA more effective.” According to the Canadian Council for International Cooperation, the budget increases announced in the last two years will only stabilize Canada’s ODA spending at around 0.27% of Gross National Product (GNP) in the short run. With the Government’s current commitment to double IAE spending by 2010, this ratio is expected to be just over 0.3% by the end of the decade – still less than half of the United Nations’ target of 0.7%. In 2001, “Canada [ranked] 19th out of the 22 Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members in terms of ODA per GNI [Gross National Income] and 11th in volume terms.” Recent budget increases have improved Canada’s relative position among DAC members: it is now the 8th-largest donor in volume terms and ranks 12th when ODA is measured as a percentage of GNI. (Comparative data on donor programs are available via the OECD’s Internet site.)

The ODA program was the object of major parliamentary reviews during 1985‑1987 and again in 1994, leading to significant policy evolution in several areas. A comprehensive strategy for Canadian international development assistance, Sharing Our Future, was publicly released in March 1988. Current policy directions were outlined in the Government Statement Canada in the World, released in February 1995.

Table 1: International Assistance Envelope Breakdown (Issuance Basis)**

Chart 1: 2003-2004 International Assistance Envelope by Channel of Delivery

A. Brief History: The Rise and Fall of Aid Fortunes

In 1968, CIDA succeeded the External Aid Office, the agency through which Canada had directed official aid to poorer “developing” countries since 1950. The budget for aid had grown rapidly from $11 million in 1950 to $279 million by 1967. In the next several decades, it reached over 10 times that amount. CIDA, however, never became a separate department. It was created without legislation and continues to operate under other statutory and spending authority. The scope of CIDA’s mandate within foreign affairs has also been ambiguous. In theory, the Agency should advise government on all matters affecting international development co-operation. In practice, the perception has grown that CIDA is more influenced by the bureaucratic environment in which it must operate, and by foreign policy and commercial exigencies, than it is influential in the policy process. The 1993 Chrétien cabinet eliminated the post of a separate minister responsible for CIDA; however, since early 1996 the Agency has been under the authority of a Minister for International Cooperation, currently the Honourable Susan Whelan. Foreign Affairs priorities nevertheless continue to shape aid policies.

In terms of volume, aid as a percentage of GNP peaked at 0.52% in 1975‑1976, then fell back to 0.42% in 1980-1981 before beginning a gradual recovery to reach 0.5% in 1986‑1987. Thereafter, it entered another period of decline despite the following commitment in the 1988 strategy, Sharing Our Future, with respect to aid levels and targets:

Canada’s official development assistance has reached .5% of GNP and will be maintained at that level until 1990‑1991. Then, it is the government’s objective to raise the ODA/GNP ratio by gradual increments, beginning in 1991‑1992, to .6% by 1995 and to .7% by 2000.

In reality, the story of the 1990s was a practical abandonment of any progress towards the internationally recognized 0.7% level.

Deficit reduction measures cut deeply into the ODA budget and Canada’s aid strategy also faced questions about its effectiveness at a time of questionable public support for aid spending. The Government did increase the IAE by an average of $95 million a year between 1997-1998 and 2000-2001, primarily via supplementary allocations made later in the fiscal year. However, in 2000-2001, Canadian ODA was still more than 20% lower than its peak in 1991-1992, and 17% lower than it had been in 1994-1995. In short, available ODA resources were substantially diminished when, in September 2000, the Minister for International Cooperation announced a shift of CIDA resources toward poverty-focused social development priorities.

B. Composition of the Aid Budget

In interpreting proposed ODA expenditures, the effect of different reporting methods and recent administrative and organizational changes must be taken into account, especially for year‑over‑year comparisons. At the aggregate level, the most important distinction has been between spending commitments (issuance basis) and financial requirements (cash basis) in a given fiscal year. Not everything counted as ODA was treated as a current budgetary expense. One main reason that commitment levels differed from actual cash outlays is that the former included promissory notes to international financial institutions (IFIs) which represent a cash drain only when they are encashed by the institutions holding them. However, as of 1998-1999, the Government considers such notes issued to IFIs as fully expended in the year of issuance. IFI encashments dropped sharply in 2002-2003, from approximately $155 million in post-Budget 2001-2002 to approximately $99 million in 2002-2003 (roughly a one-third reduction in spending). The reduced budget for IFIs in 2002-2003 also reflects the fact that payments and issuance notes for Canada’s international obligations to selected multilateral organizations and institutions during the 2002 calendar year were attributed to the 2001‑2002 fiscal year. In 2003-2004, IFI encashments will increase to almost $115 million.

During the 1990s, another factor was a substantial growth in some non‑cash components of ODA, notably: the imputed value of support for developing-country students attending higher education institutions in Canada; refugee costs; official debt relief; and the concessional portion of some export credits counted as ODA.

In 1988, the ODA program was divided into two parts, of roughly equal weight and funding: a Partnership Program to support activities by Canadian and international partner agencies (NGOs, development banks, etc.), and a National Initiatives Program for bilateral assistance on a mainly government‑to‑government basis. In 1996 there was a further organizational realignment to assist operational performance and reporting on activities by CIDA’s “business lines”: geographic, multilateral, Canadian partnership, countries in transition, communications, policy, and corporate services. The following briefly outlines the major bilateral, multilateral, and non‑governmental channels of CIDA’s program funding, as well as those components of the ODA program not administered by CIDA.

1. Bilateral Aid (Geographic Programs)

Bilateral ODA supports well over 1,000 projects in more than 100 countries, agreed to by Canada and the recipient government. Until 1988, 80% of procurement for such bilateral government‑to‑government aid had to be sourced in Canada. The Canadian content of the goods and services purchased had to be at least 66.67%. Critics argued strongly that the effect of this “tying” is to reduce significantly (on average by about 20%) the value of such assistance to the recipient. A related concern is that tied aid, by acting as a hidden subsidy to domestic exporters, distorts the priorities of the aid program by giving too much weight in the selection process to commercial interests in the donor country. Since 1988, tying rules have been significantly liberalized, except for food aid. The general bilateral requirement was reduced from 80% to 66%, and to 50% in the case of sub‑Saharan Africa and least-developed countries in other regions. The government’s 1995 policy statement did not accept the recommendation of the Special Joint Committee Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy that Canada work within the DAC to lower the proportion of tied aid to 20% by the year 2000.

Domestic factors and Canadian interests continue to play a large role in the determination of country eligibility criteria for bilateral aid. But development interest is supposed to be primary. Instead of the old three-category system, all developing countries, except for a small excluded list, can be eligible. The aim of the 1988 strategy, however, was to achieve more bilateral aid concentration, with 75% of it going to 30 countries or regional groupings; 65% was to go to Commonwealth and Francophone countries. In 1995-1996, the allocation among regions was: 44% to Africa; 36% to Asia; and 20% to the Americas. According to OECD reports, the distribution of Canada’s bilateral assistance in 1999-2000 was (figures in US$) as follows: sub-Saharan Africa $202 million; South Central Asia $90 million; other Asia and Oceania $107 million; Middle East and North Africa $34 million; Latin America and the Caribbean $125 million; Europe $50 million; and $582 million not specified as to region. More recently, CIDA has increased its aid focus on African countries. The regional distribution of aid has begun to shift with the creation of the Canada Fund for Africa (with a commitment of $500 million over three years) and an increasing focus on a few countries – mostly in Africa – that meet aid effectiveness criteria and demonstrate a commitment to democracy, good governance and human rights.

For eligible countries, Cabinet annually establishes confidential five‑year bilateral planning figures taking into account the following criteria: the country’s needs; the country’s commitment and capacity to manage aid effectively; the quality of the country’s economic and social policies, or its commitment to improving its policies; Canada’s political and economic relations with the country; the country’s human rights record; and the country’s commitment to involving its population in development.

CIDA’s planned spending for the geographic programs sector is about $1.2 billion in fiscal year 2003-2004, up approximately $372 million from last year’s level. As previously mentioned, this constitutes 40.7% of the IAE.

Multilateral aid is help that Canada gives to other countries through contributions to some 85 international agencies (chiefly United Nations) and financial bodies. In 2003-2004, funding for CIDA’s multilateral programs will total $411 million, or 14% of the IAE. The rubric of “programming against hunger, malnutrition and disease” in the Estimates (see Table 1) includes both multilateral and bilateral food aid.

Among the multinational organizations that Canada supports are the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the World Food Program (WFP), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the UN Fund for Population Activities (to which funding has recently been cut, however). As well, Canada contributes to the World Health Organization, relief for refugees, international farming research, and Commonwealth and Francophonie technical co-operation funds. Canada’s contributions are mostly annual UN assessments, multi-year pledges, or humanitarian aid channelled through the multilateral agencies. The Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs – the World Bank Group and development banks serving Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Caribbean) have also received substantial support from Canada. Indeed, cumulative contributions to the MDBs had reached over $19 billion by the end of 1993, consisting of subscriptions of over $12 billion in paid-in and callable capital, and almost $7 billion in ODA contributions to the banks’ concessional funds.

3. Canadian Partnerships (Voluntary Sector Support, Education and Business Co-operation)

Many Canadians are anxious to supply the needs of poorer countries through non‑governmental channels. NGOs, through effective, low‑cost development projects, promote self‑reliance to meet grass‑roots needs. CIDA matches donations to nearly 350 private voluntary agencies. Planned spending for CIDA’s Canadian Partnerships in 2003-2004 is virtually unchanged from the previous year at $253 million and constitutes just under 9% of the IAE. Included in the Voluntary Sector and Special Projects Initiative are the Youth Employment Initiative and the International Forum of Federations.

During the 1980s, the generous response of Canadians to the African famine drew increased attention to the use of NGO channels to deliver aid. Also, in light of the decentralization of some CIDA operations, new forms of NGO/government partnership have gained wider application within the aid delivery process. Despite public support for giving them a larger role, NGOs have faced increasing worries about financial vulnerability and how to maintain their independence. NGOs were especially hit hard by the February 1995 Budget, when they absorbed a cut of 18.5%.

Current policy has upgraded the role of higher education institutions, in addition to creating centres of excellence and regional information centres. By 1993, the number of scholarships for Third World students was scheduled to double, to 12,000 annually, about half of these scholarships being for education in Canada. By 1997‑1998, combined CIDA and DFAIT funding reached $17.2 million. In terms of development education and “public outreach” activities, which have a target budget of 1% of ODA, only $3.5 million was spent on “development information” by CIDA in that year. Funding for NGO development education was cut back considerably during the 1990s.

Industrial co-operation has become an important area of CIDA’s activity. The Canadian Partnership Branch (created in September 1991, replacing the Business Cooperation Branch and the Special Programmes Branch) helps to direct Canadian private investment into business efforts likely to profit developing countries and Canadian firms. CIDA finances starter and viability studies by Canadian companies investigating joint ventures in developing countries. The use of Canadian business to support private-sector development in these countries should be distinguished from the use of aid to support rich country exports. Most experts in the development field strongly object to so‑called “mixed credit” approaches because, they argue, commercial investments and export promotion should not be pursued under the guise of “aid.” Current policy emphasizes more private-sector initiatives as a key part of human resource development in the field. The industrial co-operation budget enjoyed large increases until recently. Planned spending on Industrial Co-operation for 2003-2004 is $56.5 million, up slightly from the previous year.

These account for approximately one-fifth of total ODA and include the following:

The Department provides Canada’s contribution to the World Bank (both the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank’s “soft loan window,” the International Development Association (IDA)), as well as to several concessional lending facilities of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The Minister of Finance is Canada’s Governor on the executive boards of the Bank and the Fund. IDA funding has been under pressure in recent years because of increased demands (notably in sub-Saharan Africa) on its limited resources and a smaller U.S. commitment to new IDA replenishments. In 2003-2004, the Department of Finance is budgeting $230.1 million for the IDA. Total payments to IFIs from the Department will constitute 7.9% of the IAE.

b. Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT)

Foreign Affairs oversees the funding of the IDRC (a Crown corporation) and makes contributions to a number of multilateral organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and to the Commonwealth Scholarship Program. The DFAIT budget for ODA grants and contributions in 2003-2004 is: $68 million for assessed contributions; $8 million for voluntary contributions; $8.3 million for scholarships; and $4.9 million for the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development. The administration of aid delivery charged to DFAIT’s budget is $52.2 million, or 1.8% of the IAE.

c. International Development Research Centre (IDRC)

The IDRC was founded in 1970 as a public corporation financed by Canada to initiate, encourage, support and conduct research into the problems of the developing regions of the world and into the means for applying and adapting scientific, technical and other knowledge to the economic and social advancement of those regions.

The international Board of Governors that sets IDRC policies consists of 11 Canadians and 10 others; the head office is in Ottawa, and regional offices are in Singapore, Bogota, Dakar, Cairo and Nairobi. The IDRC’s budget for 2003-2004 will remain stable at $92.5 million. The IDRC has sponsored more than 1,000 projects in 100 countries. It has managed to retain its independent status and, since the 1992 Rio Conference, has taken on a more prominent role on environmental issues.

d. The International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (ICHRDD)

The idea for a new ODA instrument was first proposed by a parliamentary committee in June 1986 and accepted by the Government in December 1986. It was then studied by two special rapporteurs who gave their proposals to the Government in July 1987. Legislation establishing the Centre was passed in September 1988, giving it a first-year budget of $1 million to rise to $5 million annually by 1992. Since 1993, the Centre has been dependent on annual appropriations. In December 1989, Ed Broadbent was appointed the Centre’s first president, and operations formally began in Montreal in June 1990. A five‑year evaluation of the Centre tabled in Parliament in February 1994 exposed some criticisms of its management and costs and led to internal changes. Mr. Broadbent was reappointed for a further three-year term early in 1995 but resigned, effective June 1996. Early in 1997, the Honourable Warren Allmand took up the post of president after resigning his seat in the House of Commons. The 2003-2004 budget for the ICHRDD will be $4.859 million, the same as the preceding year. As an arms-length body, the ICHRDD, which has since changed its short title to “Rights & Democracy,” is able to work with overseas partners at the leading edge of sensitive human rights and democracy issues.

e. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

Based in Winnipeg, the Institute has been operating since 1991. It does not have separate legislative status but, like the IDRC and ICHRDD, has international board members. The IISD’s annual budget has increased from about $5 million in the mid-1990s to $10.72 million in fiscal year 2001-2002. The federal government (through CIDA and Environment Canada) has contributed significantly to its core funding, as has the Government of Manitoba. Operating grants from these sources made up $2.26 million in fiscal year 2001-2002. The IISD’s project-related funding (designated grants) comes from various federal departments and agencies, the provinces, foreign governments, international organizations, and the private sector.

The provinces have also been involved in international development through contributions to institutional co-operation and matching grants to assist the work of NGOs. Contributions from provincial governments were $23 million in 1997-1998.

Canadian aid philosophy has been criticized as slow to move away in practice from a traditional emphasis on large capital projects and commodity transfers. Yet already in the Agency’s 1980‑1981 Report, then CIDA President Marcel Massé stated:

CIDA is now investing more heavily in human capital, shifting the focus from projects that build economic infrastructure to those that build education, health, and people‑to‑people relationships. A key part of what we have learned is that we must respect the right of others to choose their own path.

In the 1970s, the Government had produced a comprehensive Strategy for International Development Cooperation 1975‑1980, which emphasized social justice, participation, and “basic needs.” A review of established aid policy was also published in 1984. It was not until 1988, however, that a reformed strategy was adopted in the wake of a 1985 government foreign policy paper and several parliamentary committee reports.

The 1988 strategy document, Sharing Our Future, effected a major policy renewal and operational reorganization of ODA, based largely on recommendations in For Whose Benefit?, the milestone report of the House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade (SCEAIT) tabled in May 1987 and also known as the Winegard report. This had argued that ODA was beset by “confusion of purpose”; the program needed a clear concentrated mandate and a streamlined, decentralized delivery system. On the policy side, the Government’s response to Winegard affirmed that: “The primary purpose of our development effort is to help the world’s poorest countries and people.” Another guiding principle was to “strengthen the links between Canadian citizens and institutions, and those in the Third World – in short, partnership.” These principles were set out in the Government’s “ODA Charter,” though not in legislation as recommended by the Committee.

The priorities for projects and programs were identified as: alleviating poverty; designing economic adjustment policies that take into account the human impact on the people they are designed to assist; increasing the participation of women in development; fostering environmentally sound development; food security; and energy availability. In 1991, CIDA adopted as its mission statement “to support sustainable development in developing countries” – incorporating, as interrelated concepts, “environmental, economic, political, social and cultural sustainability.”

This aid policy framework has been challenged by controversies over the weight given to human rights, the impact on the poor of the market-oriented “structural adjustment” programs demanded by donors and international financial institutions (IFIs), and the effectiveness and sustainability of aid interventions. Canada has been pushed to do more in the “social priority” areas of primary health care and education, family planning and rural water supply in developing countries (by some estimates, less than 10% of ODA). Indeed, the 1991 United Nations Human Development Report ranked Canada 10th among donors in this regard. In 1995, agreeing with the recommendation of the parliamentary foreign policy review committee, the Government committed itself to devoting 25% of ODA to “basic human needs.”

The Sharing Our Future policy framework came increasingly under strain during the 1990s as CIDA confronted fiscal pressures along with the demands of a post‑Cold War environment. Restraint measures in successive budgets also meant trying to implement policy and organizational changes in a context of diminishing resources and therefore cutbacks in most programs. Meanwhile, many NGOs were increasingly concerned about CIDA’s direction. For example, an October 1991 report by the Inter‑Church Fund for International Development and the Canadian Council of Churches argued that by concentrating on structural adjustment programs CIDA was “moving further and further away from the real development issues that face the poorest countries.” Goals set out in the Winegard report – increasing aid as a percentage of GNP, spending more on health care and education, and reducing the amount of tied aid – had not been met.

Also problematic was how to restructure CIDA so that it could better deliver on its mandate. A Montreal‑based consulting firm, Groupe Secor, called in to conduct a “strategic management review,” stated in a report released in November 1991 that CIDA, in attempting to meet budgetary constraints, was devoting far too many of its resources to paperwork and process. The Secor Report recommended that CIDA streamline its operations to focus on fewer “core” countries while concentrating more on strategic analysis and planning. It also suggested that program delivery be handed over to non‑profit or business‑sector partners. This last recommendation was similar to a government proposal leaked to the press in May 1991, which broached the idea of turning CIDA into a “cheque‑issuing agency” that would contract out the majority of its work to the private sector, developmental institutions and non‑governmental charities.

While the Secor exercise led to some internal reforms within CIDA, the broader questions awaited the 1994 foreign policy review. In the meantime, the Auditor General’s 1993 Report, Chapter 12 of which looked at CIDA’s bilateral programs, identified a number of problems and suggested a better defined and concentrated approach would be more effective. Similarly, a blue ribbon report released by the “Canada 21” Group in March 1994 recommended that “CIDA substantially reduce its management staff … [and] develop clear criteria and methods to evaluate the effectiveness of the assistance it gives” (Canada and Common Security in the Twenty-First Century, p. 39).

Among the most difficult policy areas has been that of aid and human rights. Intense debate has surrounded the appropriateness of bilateral programs for countries such as China which are accused of gross human rights violations. Successive parliamentary committees have advocated a more regular, public and transparent process for making ODA determinations on human rights grounds. A “Human Rights and Good Governance Unit” has been created within CIDA’s Policy Branch, and in early 1996 a new policy framework was released that focuses on the positive integration of human rights and democratization objectives into Canada’s aid programs. Canada must also grapple with the question of whether to offer assistance to developing countries that spend excessive sums on their military or in which there are persistent problems of corruption.

Another set of issues demanding more attention in aid strategy are those of environmental sustainability. Developing countries are being encouraged to address environmental impacts within their development plans. CIDA has examined the requirements of Canadian environmental assessment laws in terms of its own practices. In May 1992, for example, CIDA decided to withdraw further funding from the Three Gorges hydroelectric project in China out of concern for the damage it would cause to farmland. Since the June 1992 Rio Earth Summit, Canada has made a number of commitments involving ODA for environmental objectives. For example, CIDA manages Canada’s contribution to the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the main UN/World Bank vehicle through which developed countries are helped to meet global environmental funding obligations.

During the 1990s, the squeeze on resources sharpened the debate over the values and objectives of Canada’s aid – effective for what and for whose benefit? NGO testimony before the 1994 parliamentary review committee argued for a stricter focus on the poorest and for 60% or more of ODA to go to “sustainable human development” that encourages reciprocal policy commitments and democratic participation by Third World partners. Other private-sector witnesses suggested that benefits to Canada must remain a key consideration guiding resource allocations.

Responding to the foreign policy review exercise and the Special Joint Committee’s Report, the Government’s February 1995 Policy Statement Canada in the World declared that:

The purpose of Canada’s Official Development Assistance is to support sustainable development in developing countries in order to reduce poverty and to contribute to a more secure, equitable and prosperous world.

The Government endorsed the program priorities of: basic human needs; women in development; human rights, democracy and good governance; private sector development; and the environment. “Infrastructure services” were added as a sixth priority. The new policy framework did not, however, take up the Committee’s recommendations for a legislated mandate for CIDA, a lower proportion of “tied aid,” a transfer of any export promotion functions out of CIDA, a concentration of aid on fewer countries, a greater share of ODA allocated through NGOs, and no further erosion of the ODA/GNP level.

The year 2000 was a pivotal year for Canadian aid priorities. Former Minister for International Cooperation Maria Minna announced a significant change in priorities for CIDA within the next five years. CIDA’s Social Development Priorities: A Framework for Action affirmed poverty reduction as the Agency’s overarching goal and outlined four priority areas for attaining this end: (1) health and nutrition; (2) basic education; (3) HIV/AIDS; and (4) the protection of children. The proposed framework advocated a more sectoral approach in the development initiatives; greater coherence with other donors; local ownership; knowledge-based development; and allocating aid to fewer countries for social development priorities. In terms of financing, by the year 2005-2006, 40% of CIDA’s annual budget was to be allocated to these priority areas, marking a significant disjuncture from the less than 20% allocation in 1999-2000. Moreover, upwards of 42% of CIDA’s available budget was to be reallocated from current priorities to these initiatives.

The following year, 2001, ushered in CIDA’s Sustainable Development Strategy 2001-2003. Within the same vein of poverty reduction, the 2001-2003 Strategy has two salient features: (1) increased integration and harmonization of CIDA’s development programming with its sustainable development policy; and (2) the goal of establishing and ensuring continuous learning and knowledge-based development. In June 2001, CIDA released the discussion paper Strengthening Aid Effectiveness: New Approaches to Canada’s International Assistance Program, on which it held extensive consultations, including with partners in the developing world. This process resulted in the release in September 2002 of Canada Making A Difference In The World – A Policy Statement On Strengthening Aid Effectiveness. This statement incorporates existing commitments and the principles of effective development formulated by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, namely, the importance of local ownership of development projects and strategies, improved donor coordination, stronger partnerships between donors and recipients, a results-based approach with improved monitoring and evaluation, and developing greater coherence between aid and other policies in industrialized countries. In addition, the document outlines three factors seen as central to ensuring the effective use of aid: good governance, enhanced capacity in public and private sectors, and engaging civil society and target groups in developing and implementing aid projects.

An important element of CIDA’s approach to improving aid effectiveness is to focus new investments on key sectors in a few countries. In late 2002, Minister Whelan announced a list of nine countries where new resources will be focused as they become available: Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, Mali, Mozambique, Senegal and Tanzania. With regard to improving the coherence of aid and other government policies in Canada, Canada Making A Difference In The World highlights the importance of untying aid and improving access to Canadian markets for least developed countries (LDCs). The latter commitment was implemented in the form of the government’s LDC Market Access Initiative, which came into effect on 1 January 2003.

Many NGOs continue to press for reforms that will strengthen the poverty reduction orientation of Canada’s aid and achieve greater coherence among Canadian policies (including those on trade, investment and agriculture) towards developing countries.

A. Linking Aid and Human Rights

The question of linking aid disbursements to the human rights situation in recipient countries has attracted growing attention from parliamentarians since the 1970s. The Carter administration’s decision to cut off U.S. aid to several gross violators of human rights inspired several Private Members’ Bills along these lines. In November 1982, a sub‑committee of the Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and National Defence (SCEAND) recommended that:

Canadian development assistance should be substantially reduced, terminated, or not commenced in cases where gross and systematic violations of human rights make it impossible to promote the central objective of helping the poor.

Human rights were gradually accepted as a legitimate factor in decisions on extreme cases (“gross and systematic” violators), but the government tended to emphasize the need for caution in other cases.

Human rights again emerged as a dominant concern during the public hearings of the Special Joint (Senate-Commons) Committee on Canada’s International Relations. Its June 1986 final report, Independence and Internationalism, agreed that human rights should be a priority of Canadian foreign policy. Specifically recommended were human rights training for foreign service officers and the creation of an International Institute of Human Rights and Democratic Development, funded out of ODA, to undertake projects aimed at preventing human rights abuses. Going beyond that, SCEAIT’s 1987 report For Whose Benefit? contained strong recommendations linking development and human rights, inter alia:

-

a comprehensive set of “guiding principles” for both emergency and long‑term situations, designed to be fair, to support NGOs, and to be sensitive to the needs of victims;

-

a CIDA policy unit and comprehensive operational framework to assist decision makers and executors, to include a basic classification matrix identifying groups of recipients along a grid from human rights “negative” to “positive”;

-

a requirement that annual reports based on the above be made public and referred for review to parliamentary committees;

-

a Canadian push “to allow human rights concerns to be put openly on the agendas of the international financial institutions”;

-

a stepped-up emphasis on positive measures of human rights promotion; and

-

the linkage of development to demilitarization, with a ban on Canadian military exports to any country ineligible for bilateral aid on human rights grounds.

The government response supported the principle of linkage but was equivocal on the practice, rejecting suggestions for a human rights grid based on country performance and for public disclosure of human rights assessments via an annual reporting mechanism. Since then, parliamentarians have continued to pursue international human rights issues. A 1990 report of the Human Rights Committee and work by a SCEAIT Development and Human Rights sub‑committee (1991‑1993) have also addressed the question of how to improve the process for making human rights determinations in foreign policy. The November 1994 Report of the Special Joint Committee Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy recommended “human rights, good government and democratic development” as one of five program priorities for ODA. The report called for a broad approach to making aid conditional. In cases of serious abuses of human rights by recipient governments, sanctions could be applied “up to and including the termination of bilateral assistance,” but Canada should continue to support the poor and vulnerable groups through the work of NGOs.

For Whose Benefit? was the first major independent study completed under the House of Commons reforms introduced in February 1986. It proposed changes at many levels of ODA policy, programming and organization. The Government, in its response, To Benefit A Better World, tabled on 18 September 1987, hailed the report, fully accepting 98 of 115 recommendations. SCEAIT had concluded its report with a strong message that aid activities could be rendered futile by a failure to resolve the critical problem of Third World debt. The government subsequently announced in 1987 that it was cancelling the ODA debts, totalling $672 million, of a number of Francophone and Commonwealth countries in sub‑Saharan Africa. Legislation to that effect was passed by the House of Commons in June 1989. In a June 1990 report on the debt crisis, SCEAIT repeated the Winegard report’s recommendation that there be a funding floor for ODA. The Government again rejected this proposal, but was open to further official debt concessions. Other parliamentary attention focused on the impact of budget cutbacks, the effectiveness of aid, human rights and “conditionality” issues, and on possible changes to CIDA to accommodate such constraints while responding to new political and economic demands.

Early in 1994, the Auditor General’s Report and the Canada 21 Report sharpened the debate over both policy and institutional reforms. The November 1994 Report of the Joint Committee Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy, after hearing a great deal of testimony on ODA issues, recommended government action to:

-

clarify CIDA’s mandate as being centred on effective poverty reduction goals, and to adopt this framework in legislation;

-

boost the portion of ODA devoted to basic human needs to a minimum of 25%;

-

lower the portion of “tied aid” (on a multilateral basis to 20% by 2000) and remove any export promotion element from CIDA;

-

make structural adjustment measures consistent with poverty reduction objectives and broader human rights and good government conditions;

-

concentrate on fewer countries where needs are greatest (e.g., in Africa); and

-

increase funding through NGO partners with demonstrated records, in line with public support for their work.

The Joint Committee also called for regular reviews of CIDA’s performance by the foreign affairs committees of both Houses. Ministers and CIDA officials have continued to appear before the Commons Foreign Affairs and International Trade Committee (SCFAIT) on the annual expenditure estimates and performance reports. SCFAIT also held a special forum in April 1996 on the theme of promoting greater public understanding of international development issues. However, the last in-depth parliamentary review of ODA policies and programs was in 1994.

1950 - Canada joined the Colombo Plan for Co‑operative Economic Development in Asia.

1960 - A consolidated External Aid Office (EAO) was set up.

1968 - The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) was created with Maurice Strong as its first president.

1969 - The Pearson Commission on International Development recommended a minimum ODA target of 0.7% of GNP for all industrialized countries.

1970 - IDRC was set up to promote technical co-operation.

1975 - CIDA’s Strategy for International Development Cooperation 1975‑1980 emphasized help to the poorest, building Third World self‑reliance and attention to basic needs.

1984 - The Hon. David MacDonald was appointed Canadian Emergency Coordinator for the African famine. $180 million was cut from the projected ODA budget.

1986 - The Hon. David MacDonald released his final report on the African famine at the end of March. The government announced a new aid program, “Africa 2000,” in early May. The Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade began a comprehensive review of ODA.

1987 - SCEAIT tabled For Whose Benefit?, its major report on ODA policies and programs. In September, the government delivered its comprehensive response, To Benefit a Better World.

1988 - Minister for External Relations and International Development, Monique Landry, released the Government’s comprehensive ODA strategy, Sharing Our Future.

- The Government introduced legislation to establish an International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

1989 - Marcel Massé became CIDA President for the second time.

- Ed Broadbent was named to head the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

1991 - The February Budget introduced the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) and restricted ODA growth.

- In October, Prime Minister Mulroney pressured the Commonwealth to establish a formal link between foreign aid and human rights.

- In November, at the summit meeting of countries of la Francophonie, Prime Minister Mulroney repeated his intention to link Canada’s foreign aid to human rights and encouraged other countries to follow suit.

1992 - Prime Minister Mulroney announced at the June Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that Canada would forgive $145 million in Latin American debt so as to free funds for environmental projects in the region.

- The government announced that it was cutting the aid budget by 10% in each of the next two fiscal years.

1993 - In March, CIDA announced the elimination of bilateral programs to Central and Eastern Africa.

- The April Budget restricted future IAE growth to 1.5% starting in 1994‑1995.

1994 - The February budget reduced IAE by 2%.

- The Auditor General’s criticisms of CIDA’s bilateral programs were the subject of parliamentary committee hearings in the spring.

- The November Report of the Special Joint Committee Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy made recommendations on reforming international assistance.

1995 - The Government Statement Canada in the World was released in February.

- The February Budget cut ODA funding by 15% in 1995-1996.

1996 - The March Budget announced a further cut of $150 million to ODA.

- The House Foreign Affairs Committee held a special forum on promoting public understanding of international development issues.

2000 - The United Nations Millennium Summit in September set global targets for the reduction of poverty and other basic development goals.

- A new social development framework document announced a significant shift in priorities for CIDA over the next five years.

2001 - CIDA released its Sustainable Development Strategy 2001-2003: Agenda for Change in February.

- CIDA released a consultation document, Strengthening Aid Effectiveness: New Approaches to Canada’s International Assistance Program, in June.

- Canada committed an additional $100 million in humanitarian aid for Afghanistan in September.

- The December Budget announced increases to the aid envelope as well as the establishment of a $500-million African trust fund.

2002 - The Prime Minister committed to annual ODA funding increases of 8% at the March 2002 United Nations Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey, Mexico.

- Canada hosted the G8 Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta, in June, with a focus on Africa through the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD).

- CIDA released its Canada Making A Difference In The World – A Policy Statement On Strengthening Aid Effectiveness in September.

- In December, CIDA released a list of nine developing countries targeted for new ODA investments.

2003 - The government’s Least Developed Countries Market Access Initiative took effect on 1 January.

- The February Budget announced an increase in the IAE of $353 million for the 2002-2003 fiscal year, and an annual increase of 8% through 2004-2005, based on this revised 2002-2003 amount. The government repeated its commitment to double the IAE by 2010.

Blouin, Chantal. “Canada’s Trade Policy Toward Developing Countries: A Post-Uruguay Round Assessment.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. XXIII, No. 3, 2002, pp. 515-542.

Brecher, Irving (ed.). Human Rights, Development and Foreign Policy: Canadian Perspectives. The Institute for Research on Public Policy, Halifax, 1989.

Brodhead, Tim et al. Bridges of Hope? Canadian Voluntary Agencies and the Third World. The North-South Institute, Ottawa, 1988.

Canada. Canadian International Development Assistance: To Benefit a Better World. Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1987.

Canada. Canada in the World. Government Statement. Ottawa, February 1995.

CIDA. Canada Making A Difference In The World – A Policy Statement On Strengthening Aid Effectiveness. Minister of Public Works and Government Services, Ottawa, 2002.

CIDA. Sharing Our Future: Canadian International Development Assistance. Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1987.

CIDA. “Strengthening Aid Effectiveness: New Approaches to Canada’s International Assistance Program.” Consultation Document, June 2001.

Clark, Andrew and Maureen O’Neil. “Canada and International Development: New Agendas.” In Ken Osler Hampson and Christopher J. Maule, eds., Canada Among Nations 1992‑1993: A New World Order?, Carleton University Press, Ottawa, 1992, pp. 219‑234.

Gillies, David. Between Principle and Practice: Human Rights in North-South Relations. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston, 1996.

House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade (SCEAIT). For Whose Benefit? Queen’s Printer for Canada, Ottawa, 1987.

Miller, Robert, ed. Aid as Peacemaker: Canadian Development Assistance and Third World Conflict. Carleton University Press, Ottawa, 1992.

Morrison, David R. Aid and Ebb Tide: A History of CIDA and Canadian Development Assistance. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, 1998.

OECD. Development Co‑operation Report: Efforts and Policies of the Members of the Development Assistance Committee. Paris, annual.

OECD (Development Assistance Committee). Development Co-operation Review – Canada. Paris, 2002.

Pratt, Cranford. “Canada’s Development Assistance: Some Lessons from the Last Review.” International Journal, 49:1, Winter 1993-1994, pp. 93-125.

Pratt, Cranford, ed. Canadian International Development Assistance Policies: An Appraisal. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston, second edition, 1996.

Reality of Aid Project. The Reality of Aid 2002: An Independent Review of Poverty Reduction and Development Assistance. IBON Books, Manila, 2002 (the section on Canada is prepared by the Canadian Council for International Cooperation – summary available on the Council’s website.

Rudner, Martin. “Canada in the World: Development Assistance in Canada’s New Foreign Policy Framework.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. XVII, No. 2, 1996, pp. 193‑220.

Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons Reviewing Canadian Foreign Policy. Canadian Foreign Policy: Principles and Priorities for the Future. Ottawa, November 1994.

“The New Development Debate,” International Journal, Vol. LI, No. 2, Special Issue, Spring 1996, pp. 191‑313.

United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. Oxford University Press, New York, annual since 1990.