Parliamentary Research Branch |

PRB 98-2E

THE GRAIN INDUSTRY IN CANADA

Prepared by:

TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) B. Canadian Grain Commission (CGC) C. Canadian International Grains Institute (CIGI) CANADA-U.S. GRAIN TRADE RELATIONS THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION, STATE TRADING ENTERPRISES (STEs), AND EXPORT SUBSIDIES A. Federal Action on

Environmental Issues B. Biotechnology and New Crops THE GRAIN INDUSTRY IN CANADA Grains grown in Canada include wheat, barley, corn, oats and rye. Among the oilseeds produced here are canola, soybeans, flaxseed, safflower and sunflower. Canada produces about 7% of the world’s total supply of wheat and barley but accounts for between 15% and 20% of world exports. This paper looks at various aspects of the Canadian grain industry, in particular:

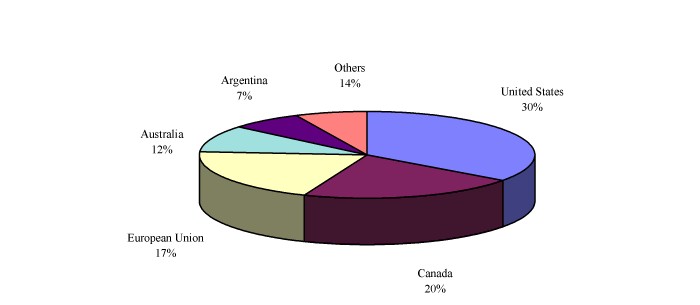

A selected chronology briefly summarizes developments in the industry since the end of the 19th century. In the Canadian West, wheat remains the main crop, accounting for approximately 60% of total grain production. Canada Western Red Spring (CWRS) accounts for almost 80% of total wheat production. Depending on growing and harvesting conditions, CWRS can range from high-quality, high-protein wheat to low-protein wheat used as feed in Canada. The second-most important class of wheat is Canada Western Amber Durum (CWAD); this high-quality durum wheat, produced in Canada, is recognized worldwide and is subject to strong demand from pasta and semolina manufacturers. In Central and Eastern Canada, winter wheats – particularly Soft White Winter – dominate production. Usually, about 90% of all Canadian wheat production is exported. Averaged over a five-year period (1994-1998), Canada occupies sixth place among the world’s major wheat-producing countries, preceded (in order of importance) by China, the European Union, the United States, India and the Russian Federation. In terms of international trade, however, Canada is the world’s second-largest exporter of wheat after the United States; with annual exports averaging approximately 20 million tonnes, this country accounts for about 20% of the world market for wheat exports.(1) Averaged over a ten-year period, China and Japan are by far Canada’s principal customers for wheat and flour, followed by Iran, South Korea, Brazil and Algeria. However, a new trend has been emerging since the early 1990s, as the United States has moved into second place as a customer for Canada’s wheat, with average imports of Canadian wheat fluctuating around 1.5 million tonnes per year. In more recent years (1996-1999), Iran, the United States, Japan, China and Indonesia have been the major customers for Canadian wheat. Canada is by far the major exporter of hard (durum) wheat, and its average annual exports amount to nearly three million tonnes, or 48% of total world exports. Algeria and Italy have traditionally been Canada’s two largest customers in this area, but demand from the United States has been growing steadily since the early 1990s. Graph 1 – Distribution of World

Export Markets for Canadian Wheat

Table 1 – Major Export Markets for

Canadian Wheat

|

|

Annual

average |

Annual

average

|

| China Japan Iran South Korea United States Brazil Algeria |

4,448 |

1,500 |

World production of coarse grains – barley, rye, oats, corn, sorghum and millet – amounts to approximately 860 million tonnes per year. Canada produced on average 24 million tonnes of these grains each year over the period from 1991 to 2000, including 12.5 million tonnes of barley. In recent years, Canadian output of coarse grains has tended to be above the long-term average, in particular because barley-growing has been stimulated by higher livestock prices.

Corn is the most important coarse grain traded on the world market, with an average annual volume of 60 million tonnes. It is followed by barley, with a volume of about 17 million tonnes per year. With exports of only 300,000 tonnes, principally from Ontario, Canada is not a major player in the corn export market. On the other hand, its annual exports of barley have averaged 3.8 million tonnes over the past ten years, allowing it to capture 22% of world trade in brewing and feed barley to become the world’s second-largest barley exporter, after the European Union. Asia is by far the biggest market for Canadian barley.

For 20 years now, canola has been the wonder crop of the Canadian West: from a cultivated area of 2.5 million hectares in the early 1980s, it had by 2000 expanded to more than five million hectares, mainly in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Although canola exports represent only 10% of world trade in oilseeds, Canada has the lion’s share of the market: its exports of more than three million tonnes a year account for 80% of total worldwide exports of canola, which amount to nearly four million tonnes per year. By comparison, Canada’s closest competitor, the European Union, exports just over 300,000 tonnes of canola a year. The main sources of demand for Canadian canola are Japan, Mexico and the United States. On the domestic market, demand for canola is growing, thanks to the development of the oil-crushing industry and the making of oilseed cake. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada estimates that the capacity of the domestic canola-crushing industry could soon exceed 12,000 tonnes a day. Although output and export levels are still far below those for wheat, there is a steady upward trend in the canola market, and the numerous private investments in the processing sector confirm that expectations are high.

But changes in world market conditions, such as the resistance to genetically modified organisms, are beginning to make their influence felt. Western producers are also responding to market signals and increasing their cultivated areas for pulses, for which world demand is booming. In Saskatchewan, for example, the area devoted to specialized crops went from 466,000 hectares in 1990 to over 2.2 million hectares in 2000.(3)

For 50 years, the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) has been the single-desk seller for the marketing of Canada’s grain. Although the volume of the world grain trade has expanded during the CWB’s period of operation, the number of players has decreased; by the early 1980s, only a handful of agencies controlled 75% of the selling and buying in the world.

The CWB’s validity as a policy instrument has always been controversial. From 1917 until the end of World War I, and then starting again in 1935, the federal government established the CWB to ensure the orderly sale of grain under difficult conditions. In its original form, the Board was a compromise tool for increasing returns and stabilizing income, and was based on voluntary participation. In 1943, when agriculture and the supply of food to Canada’s allies once again became an important national goal, farmers’ participation in the CWB became compulsory.

The CWB had in 1949 also become the sole marketing agency for oats and barley; however, oats were removed from CWB jurisdiction on 1 August 1989 and barley bound for the United States was removed on 1 August 1993 by Order in Council. On 10 September, within ten days of its date of application, the Federal Court dismissed this decision on the grounds that such a change could be made only through legislation passed by Parliament, not by Cabinet order. The challenge had come from Prairie Pools Inc., which argued that the CWB’s orderly marketing powers were too historic and fundamentally important to be arbitrarily altered by Cabinet decree. Because there were indications that a solid majority of growers opposed the removal of barley from the CWB’s jurisdiction, producers called for a plebiscite on the issue. On 20 November 1993, the new Liberal government announced it was dropping a court appeal of the 10 September decision (which had been initiated by the outgoing Conservative government). The barley issue continued to fester until a referendum in early 1997 demonstrated that 63% of Prairie farmers supported marketing their barley through the Board.

The CWB’s chief mandate is to market wheat grown in western Canada on the most advantageous terms for western Canada’s grain producers, who pay all costs of Board operations. The designated area includes the three Prairie provinces and a small part of British Columbia. The CWB is the sole marketing agency for export wheat and barley and the main supplier of these grains for human consumption in Canada. Canadian feed grains for domestic consumption can be marketed either through the CWB or direct to grain companies. The CWB is a large grain marketing agency, with annual sales between $3 billion and $6 billion.(4)

Through the operations of the CWB and its pool accounts, Prairie grain farmers are paid a price for their grain reflecting overall market conditions rather than the day-to-day fluctuations of international trade. The CWB administers the government-guaranteed initial prices paid to producers and operates a system of annual averaging (pooling) of producers’ prices. The CWB keeps separate accounts, or pools, by crop year for each grain it markets. As soon as the CWB receives payment in full for all grain delivered to it by producers during any pool period, it deducts marketing costs to determine the surplus in each pool. This surplus is distributed as a final payment on the basis of producer deliveries to that pool. If a deficit occurs, the Canadian Wheat Board Act states that losses shall be paid out of moneys provided by Parliament. The Governor in Council designates a member of Cabinet to act as Minister for purposes of the Act.

Table 2 – CWB Price Pooling

Deficits Since 1943

Wheat and Barley

(in millions of dollars)

Year |

Wheat |

Barley |

1968-69 |

140.0 |

34.0 |

Note: The only

durum wheat pool deficit was in 1990-91 ($69.6 million).

The only malting barley

deficit was in 1986-87.

The CWB uses the primary elevator companies located in grain-producing areas across western Canada to: accept delivery of grain from producers; make an initial payment; and store, handle, and ship CWB grain as required. The CWB generally does not own or operate physical marketing facilities but uses various grain-handling and marketing companies as agents to buy, handle, and sometimes sell grain on its behalf.

The Board sells to state trading agencies or to international grain companies. For their part, customers from 70 countries are provided with a wide variety of sales and delivery options. The overall marketing strategy of the CWB can best be characterized by its objective, which is to ensure that the kinds and quantities of grain needed to meet sales commitments are delivered where and when required.

Whether the CWB should continue to market barley to the United States is only one of the questions being asked about the CWB’s role as a single-desk marketing agency. Since the advent of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 1989, the U.S. government has alleged that certain Canadian exports are violating the Agreement; these alleged items include hogs, softwood lumber, cattle and durum wheat. In February 1993, the bi-national trade adjudicating panel absolved the CWB of dumping durum across the U.S. border, but recommended an annual confidential audit of CWB selling practices.

Despite this finding, the North Dakota Wheat Commission continued to use its bargaining power within the context of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement, signed in January 1994) to lobby for trade sanctions against Canadian durum imports. Late in 1993, it accused the CWB of using “liberal freight subsidies and predatory pricing practices” to gain unfair trading advantages. According to Canadian industry officials, their U.S. sales had increased because the United States was exporting large volumes of durum wheat under its Export Enhancement Program, thereby depriving domestic processors of the durum they need to make pasta and creating a premium market for top-quality Canadian durum.

In mid-January 1994, President Clinton ordered the International Trade Commission to conduct a six-month study of Canada’s durum trade practices. (Canada exported 708,000 tonnes of its total 2.25 million tonnes of durum to the United States during the 1992-93 crop year.) The results of the first independent audit of the CWB for the period 1 January 1989 to 31 July 1992 were released on 10 March 1994. Of the 105 contracts for durum wheat sales completed, only three were found not to be in compliance with Article 701.3 of the FTA, which requires that the CWB not sell durum wheat to the U.S. below the acquisition price of the goods, plus any storage, handling or other costs incurred with respect to them.

On 22 April 1994, the United States notified the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) Secretariat of its intention to renegotiate tariffs on wheat and barley under Article 28. After signalling its intent, the U.S. would have to wait 90 days to impose new tariffs on durum wheat, after which Canada would also be free to cut off U.S. exports of equal value. Possible targets were U.S. wine, pasta and breakfast cereals. The Canadian dairy and poultry industries expressed concerns that the supply management system might be threatened by efforts to placate the U.S. wheat states.

Under the terms of a bilateral agreement with Canada reached 1 August 1994, the United States said it would not pursue renegotiation under Article 28, thus avoiding a potential food trade war. The agreement, valid to 12 September 1995, imposed punitive tariffs on wheat exports to the U.S. above 1.5 million tonnes; a record-setting amount of 2.5 million tonnes was shipped south in 1993-94. The deal did not affect the 400,000 tonnes of barley, semolina and wheat, mostly from Quebec and Ontario, not handled by the Canadian Wheat Board.

A Canada-U.S. joint “blue ribbon” commission was established in September 1994 and given a year to study the dispute and half a year to make preliminary recommendations. On 22 June 1995, the Canada-U.S. Joint Commission on Grains released its interim report which recommended the elimination of discretionary pricing policies in both countries. This would mean ending the U.S. Export Enhancement Program and having the CWB operate “more at risk of profit or loss in the marketplace,” with greater transparency in its pricing methods. The CWB’s price-pooling practices were said to be undercutting prices, even though its mandate is to operate in a business-like manner and to sell wheat for no less than market value. The Commission recommended allowing producers to decide for themselves whether to participate in Canadian wheat and barley pools. The final report (11 September 1995) elaborated on the operation of the two grain marketing systems and recommended the establishment of a Consultative Committee to address short-term cross-border issues.

Supporters of the CWB say U.S. pressure since the coming into force of the Free Trade Agreement is responsible for moves to reduce the CWB’s marketing powers. In their view, it is the government guarantees on initial prices and central desk selling that allow the CWB to deliver higher returns to Prairie farmers (see the section “Canada-U.S. Grain Trade Relations”).

Since the late 1980s, a growing number of the CWB’s critics have been asking for more transparency in CWB dealings and for farmers to have more pricing options. Memories of the battle that created the CWB out of the chaos and weakness of the free market of the 1920s and 1930s are now dim. Progressive farmers are no longer necessarily those who see strength in cooperative action; the young generation of commercial farmers shows evidence of preferring individual management skills to collective approaches. It is clear that the CWB’s formerly unchallenged position became more controversial in the freer trading environment of the 1990s.

In October 1990, a Review Panel released its report on the challenges and opportunities facing the CWB in the 1990s and beyond. As well as looking at marketing, transporting and handling grain, the Review Panel recommended that the CWB relinquish its five-person team of politically appointed Commissioners in favour of a corporate structure made up of a President and Vice-President chosen by a part-time Board of Directors. Farmers would be a majority on the Board of Directors, which would also include representatives of industry and government. A corporate structure would purportedly make the CWB more accountable to its shareholders, i.e., the farmers of Canada, while the chief executive officer would be free to operate the day-to-day running of the CWB.

In response, the Board adjusted its pooling system in the spring of 1992 to allow farmers to truck their grain to U.S. export markets direct, rather than through the elevator system; however, the Board vehemently opposed giving up its monopoly role in the marketing of barley to U.S. customers. Consequently, individual farmers began defying the Board’s role and marketing their grain to the U.S themselves. The Cabinet responded on 17 May 1996 by approving an order requiring wheat and barley exporters to show an export permit from the Canadian Wheat Board at the U.S. border.

In an attempt to end the acrimony over how wheat and barley are sold, in 1995 Agriculture Minister Ralph Goodale appointed a nine-member Western Grain Marketing Panel to look at all aspects of Canadian grain marketing, including the CWB monopoly. On 9 July 1996, the Panel released the findings of the year-long study. It recommended allowing a quarter of western Canada’s annual $5-billion wheat crop to be sold at market prices, along with all of the $250-million feed-barley crop. The CWB would remain the sole buyer of both categories of wheat, paying either the current spot price or the average pooled price as the grower chose. The Panel also made recommendations respecting the governance and accountability of the CWB. The findings did not seem to resolve differences in the farm community over the CWB’s role.

On 3 December 1997, the government introduced amendments to the Canadian Wheat Board Act.(6) Bill C-72 proposed turning the Crown corporation into a mixed enterprise to be directed by a full-time Chief Executive Officer and a part-time, partially elected Board of Directors. It proposed that any changes to the Board’s monopoly on wheat and barley marketing would be subject to Order in Council and producer vote.

Bill C-72 was referred, on 19 February 1997 and before Second Reading, to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. The Committee heard from about 100 witnesses and made some major amendments to Bill C-72, particularly regarding the corporate governance of the Canadian Wheat Board. The bill as amended by the Standing Committee was reported to the House of Commons on 16 April 1997.

The amended version of the bill provided that ten directors would be elected by the grain producers. Other amendments further increased the power of the Board of Directors and clarified the status of the CWB and the role of the contingency fund. Bill C-72 died on the Order Paper when Parliament was dissolved on 25 April 1997 for a general election.

On 25 September 1997, Bill C-4, An Act to amend the Canadian Wheat Board Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, received First Reading in the House of Commons. It was referred, on 8 October 1997 and before Second Reading, to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. Bill C-4 is essentially based on Bill C-72 as amended by the Standing Committee in April 1997, with some technical and other changes.(7) The most substantive changes would allow for the CWB’s mandate to be extended to other grains and for its Board of Directors to designate one director as Board Chair. The Committee made one or two additional changes when it reviewed the bill, the most significant of which would clarify that only producers of a grain would be able to ask the Minister to have that grain added to the CWB’s mandate. Provision was also made to ensure that the farm community would have adequate public notice of such a request. The bill was reported back to the House of Commons on 7 November 1997.

Between 24 March and 2 April 1998, the Standing Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry held public hearings on Bill C-4 in Brandon, Regina, Saskatoon, Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg. The Committee heard from 92 individual farmers, 34 farm organizations, and three provincial Ministers of Agriculture. In Ottawa, the Committee also heard from the Minister responsible for the CWB, as well as officials from the CWB and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

In its report tabled in the Senate on 14 May 1998, the Committee recommended that:

i) the Board of Directors be consulted on the appointment of the President of the corporation;

ii) the Auditor General of Canada be authorized to audit the corporation; and

iii) clauses on inclusion and exclusion of grains be deleted altogether.

The Standing Senate Committee also recommended that electoral districts for the election of producer directors be structured so that:

five directors would be elected from Saskatchewan, three from Alberta, and two from Manitoba;

each permit book holder would have one vote;

the contingency fund would be capped at $30 million; and

individual accounts would be established for the three activities financed by the contingency fund (adjustments to the initial payment, early pool cashouts, and potential losses from cash trading).

Bill C-4 received Royal Assent on 11 June 1998.

A. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC)

Under the Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food Act, the Minister is responsible for the management and direction of the Department and its operations and for the administration of 30 Acts.

The name of the Department changed to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (from Department of Agriculture) in 1993 when other government services relating to the agri-food industry were transferred to it from the departments of Industry, Science and Technology and Consumer and Corporate Affairs in order to bring all the agri-food services under the umbrella of one department.

A Rural Secretariat was established in Winnipeg in February 1994 to address issues of particular concern to Canada’s rural areas.

In its Report on Plans and Priorities 2001-02, the Department says that its mandate is “[t]o provide information, research and technology, and policies and programs to achieve security of the food system, health of the environment and innovation for growth.”(8)

B. Canadian Grain Commission (CGC)

By authority of the Canada Grain Act, the mandate of the Canadian Grain Commission is to administer a rigorous quality, health and quantity assurance program, extending from farmers’ fields to end-use processing: it is meant to ensure grain of consistent quality that meets contract specifications.

Except for the costs of those activities related to food safety, research and development (R&D), and the supervision of commodity futures trading, the CGC finances most of its business costs from service fees.

In 1992, the CGC became a Special Operating Agency and in April 1995 began to function as a revolving fund. This operating authority allows CGC to take a more flexible, business-like approach to meeting industry needs.

C. Canadian International Grains Institute (CIGI)

The Canadian International Grains Institute (CIGI) was created in 1972 as a non-profit educational facility offering instruction in grain handling, transportation, marketing and technology. The CIGI tests the suitability of various grains and/or new processes in products consumed throughout the world. CIGI is funded 60% by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and 40% by the CWB.

CANADA-U.S. GRAIN TRADE RELATIONS

When two countries trade nearly a billion dollars worth of goods and services of all sorts between themselves every day, frictions are bound to arise from time to time. The agri-food business is no exception to this rule, and the grains sector in particular has seen more than its share of disputes for some years.

Especially high exports of Canadian wheat in 1993-94 exacerbated these disputes to the point where the two countries signed a trade agreement in August 1994 placing limits on Canadian exports. That one-year agreement allowed Canada to export a total of 300,000 tonnes of durum wheat at a minimum tariff of US$3.08 per tonne, which was the NAFTA tariff at that time. It was also agreed to reduce this tariff to US$2.31 in 1995. For exports within a band of 300,000 to 450,000 tonnes, the agreement called for a tariff of US$23, and all exports in excess of that band were to be subject to a prohibitive tariff of US$50 per tonne. The agreement also provided that, for all other categories of wheat, the minimum tariff under NAFTA would apply for exports up to 1.05 million tonnes: beyond that threshold, a prohibitive tariff of US$50 per tonne would come into effect.

In 1996-97, when the Americans found that the pace of Canadian wheat exports was following essentially the same trend as in 1993-94, they again demanded that limits be imposed. This reaction would seem to indicate that, even though the 1994 agreement was supposed to apply for only one year, it has set a precedent that the Americans are taking as a point of reference. In the end, no measures were taken, because the rate of exports declined towards the end of the 1996-97 crop year, leaving total wheat exports for that year as a whole at about 1.6 million tonnes.

In July 1995, in the wake of the trade agreement, the then Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Hon. Ralph Goodale, set up a committee to conduct an exhaustive examination of issues relating to the marketing of Western grains. In its report, published a year later, the Western Grains Marketing Committee issued a series of recommendations that were, on the whole, well received by the grain industry. Although the government drew heavily on the Committee’s report in preparing Bill C-72, An Act to amend the Canadian Wheat Board Act, the bill received a much cooler reception than had the actual report, suggesting that the drafters of the bill had not gone as far in restructuring the CWB and the marketing of wheat in general as the industry would have liked.

Bill C-4, which replaced Bill C-72 when the latter died on the Order Paper at the end of the 35th Parliament, received Royal Assent on 11 June 1998. However, the changes made to the CWB have not been sufficient to stop American attacks on Canada’s grain marketing practices. In September 2000, the North Dakota Wheat Commission asked the American Trade Representative to investigate Canada’s policies and practices under article 301 of the American Trade Act of 1974. This investigation, carried out by the U.S. International Trade Commission, “marks the ninth time in 11 years that the U.S. government has targeted Canadian grain trading practices. None of these investigations has confirmed the ill-founded allegations that continue to be made in the United States. Canada continues to assert that the CWB operates in compliance with international trade rules.”(9)

The U.S. government’s grain export program (Export Enhancement Program) often leads to domestic shortages; Canadian wheat can then be imported without harming the American market. Even though the imported Canadian wheat is only responding to normal demand, some Americans consider it to be the result of a Canadian plot to displace American wheat. Thus, U.S. politicians representing the border states regularly denounce Canadian wheat exports and, as a result, trade tensions between the two countries fluctuate with the grain market. In December 1998, Canada and the United States signed a Memorandum of Understanding and an Action Plan designed to facilitate trade in agricultural products between the two countries, a sector worth approximately $23 billion in any given year. The Action Plan provides that the two parties will meet quarterly to exchange information on grain market developments and perspectives between the two countries. Although the discussions are usually productive and help to smooth out certain trade irritants, the political pressures that spark some of these irritants are sometimes too strong for confrontation to be avoided.

THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION, STATE

TRADING

ENTERPRISES (STEs), AND EXPORT SUBSIDIES

The Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations (MTN), which concluded in 1994, led not only to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) but also to the birth of a new order in world trade, by bringing about reductions in export subsidies and domestic support programs and promoting greater market access through the introduction of a tariff rate system to replace the varied and complex trade barriers that existed previously. One of the anticipated effects of the new tariff structure is greater transparency in commercial transactions between countries.

For Canada’s grain trade, the major impact of the MTN has been to eliminate the “Crow rate” system (Western Grain Transportation Act), which was a direct subsidy to grain exports. Because Canada maintains no other export subsidy for grains, and because the domestic support it gives producers is in line with WTO rules, Canada should now in principle be viewed as a fair trading partner; however, this is not the case. After years of attacking the Crow rate, the Americans have now shifted their attention to the Canadian Wheat Board, which is the only remaining target.

Although they did not feature as a major subject of discussion during the most recent MTN, state trading enterprises (STEs) such as the CWB were nonetheless subjected to an examination that served to define them more closely, and thus to identify more clearly the regulatory framework within which they operate.

What is an STE? The 1994 Understanding Concerning the Interpretation of Article XVII of the GATT defined trading enterprises as follows:

Governmental and non-governmental enterprises, including marketing boards, which have been granted exclusive or special rights or privileges, including statutory or constitutional powers, in the exercise of which they influence through their purchases or sales the level or direction of imports or exports.(10)

The WTO Secretariat notes that 16 member countries have a specialized STE engaged in the wheat trade. The best known and most important of these are the Australian Wheat Board and the Canadian Wheat Board. The structure of the latter rests on three pillars: its role as a single-desk seller, its relationship with the federal government, and price pooling. The CWB is the object of regular attacks by the U.S. government.(11)

A Canada-U.S. Joint Commission on Grains, created pursuant to the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA), was mandated to examine the structures for marketing grains between the two countries, and to suggest approaches for resolving grain trade disputes. In its final report, submitted in October 1995, the joint commission concluded that:

The CWB does not receive export subsidies from the Canadian government for its pooled marketing operations; the producers assume the cost of marketing grain products sold by the Board.

The government-guaranteed initial price, which is set by regulation, is not an export subsidy, because it is applied indiscriminately to grains sold on both the domestic and export markets.

Canada is in compliance with Article XXVII of the WTO’s General Agreement, and has notified the Council for Trade in Goods that the CWB is a state trading enterprise.

Nevertheless, the Joint Commission stressed that the discretionary pricing policies that the CWB is able to pursue, thanks to its monopoly position, have the potential for distorting trade. It recommended therefore that the CWB should no longer have this advantage, and that the Board should be more open to the “risk of profit or loss in the marketplace, or conducting itself in an equivalent manner, without precluding the use of pooling […].”(12)

The Joint Commission’s conclusions did not prevent 18 members of the U.S. Congress from asking the General Accounting Office (GAO), the equivalent of Canada’s Auditor General, to investigate the capacity of STEs in Canada, Australia and New Zealand to create distortions in export markets.

In its June 1996 report, the GAO noted that officials of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) had admitted to having no tangible proof that the CWB was violating trade rules. At the same time, however, it said that the CWB’s monopoly position and its relationship with the federal government – in other words, the first two pillars of the CWB – do have the potential to create trade distortions. In effect, the GAO continued the argument put forward by the Canada-U.S. Joint Commission.

Because STEs are allowed by the WTO, their operations are subject to the Organization’s general rules and must also obey their own regulations, as clarified during the Uruguay Round. Thus, the CWB must “in its purchases or sales involving imports or exports, act in a manner consistent with the general principles of non-discriminatory treatment set out in the General Agreement for governmental measures affecting imports or exports by private traders.”(13)

Of course, the CWB will sometimes pursue discriminatory pricing policies in various markets, particularly to counter unfair trade practices such as the export subsidies used by competitors. At first glance, it might appear that the CWB is not respecting the WTO rules; however, it should be noted that an addendum to Article XVII specifies that [Translation] “the provisions of this article do not prevent a state enterprise from selling a product at different prices on different markets, provided that it acts in this way for commercial reasons, in order to satisfy the play of supply and demand on export markets.”

As can be seen, the CWB as an STE has a recognized status under the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, as well as under the WTO. It has nonetheless been a target for the United States government, which has already announced its intention of keeping STEs on the agenda of multilateral trade negotiations. This approach may stem from the political interests of U.S. pressure groups, which would like to see the United States increase its market share, or it may be part of a U.S. strategy to divert attention from its own Export Enhancement Program for grains. The fact is that both the United States and the European Union subsidize their grain exports to certain markets. Canada has always stood firm in the face of various attacks on the CWB, as shown from its reply when the North Dakota Wheat Commission criticized the Board in September 2000: “[T]he Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) is structured and operates as an independent commercial entity, in full compliance with international rules.”(14)

In examining the behaviour of STEs and their capacity to create market distortions, it is important to look beyond their unique position as a domestic monopoly and beyond the government guarantees that they enjoy. Other factors such as the amount of domestic support, export subsidies and market access – all conditions that make for market strength – can cause distortions just as readily.

Moreover, economic theory demonstrated long ago that a large share of the world market is needed to have any real influence on trade in any product. Is the CWB, which has a 20% share of the world wheat export market, really a sufficiently important player to “control” that market? There is certainly room for doubt. The CWB would appear to be merely a “price taker” on the world market, even if it must be admitted that some studies have contested this position. It is true that the CWB, thanks to its monopoly in the Canadian wheat export market, can practise price discrimination in certain markets, and can exact premiums that would be impossible if other Canadian sellers were competing for the same market share. At the same time, when the CWB comes face to face with competition from producing countries that provide export subsidies, its only defence is indeed to rely on price discrimination.

Given the circumstances in which grains are marketed, where competition is often fierce and market segmentation and price discrimination are frequently used, the CWB’s economic behaviour does not appear substantially different from that of the large private companies active in the same sector, except for one significant advantage: the system of an initial payment, followed by a final payment at the end of the crop year, permits the CWB to assume lower risk than does a grain company, which has to pay the full price up to delivery.

A. Federal Action on Environmental Issues

1. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Sustainable Agriculture Strategy

Over the past decade, farmers adjusted their farming techniques in order to support environmentally sustainable agriculture. They re-introduced crop rotation, reduced tillage and summer fallow, and enhanced shelter belts. More diversification and greater integration of livestock and crop operations are evident, as are conservation and stewardship plans.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has now developed a strategy for integrating environmental factors into day-to-day decision-making by the sector and government. The strategy is intended to promote stewardship and sustainable use of the agricultural resource base in order to explore innovative solutions to environmental challenges. It also aims at increasing industry awareness of environmental marketing and trade opportunities and constraints.

Performance indicators have been developed to measure and report on the success of implementing the strategy. Every three years, the strategy will be updated, to enable the sector and the department to build on what has been achieved.

2. Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA)

In spring 1995, responsibility and resources for federal pesticide regulation were consolidated in an agency within Health Canada. This was a major step in the reform of the pesticide regulatory system.

Until that time, all pest control products used in or imported into Canada had to be registered according to provisions of the Pest Control Products Act (PCPA) and Regulations, administered by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, with advice from Health Canada, Environment Canada and Forestry Canada (since disbanded). The products regulated are diverse and include pesticides and pest management agents used in agriculture, forestry, industry, public health and in households.

The need to revise the pesticide system became evident throughout the 1980s when, in successive policies, the federal government attempted to deal with patent protection for new chemical products. A consultation paper outlining various options that included significant data protection was released in the summer of 1987, but it was not until 1989 that the government undertook an independent review of the entire system.

The 12-member Pesticide Review Team included representatives from health, environment, labour, research and consumer groups as well as from the farm, forestry and chemical industries. In December 1990, after 18 months of work and public consultations, the team presented 28 recommendations for a Revised Federal Pest Management Regulatory System to the federal government.

The government’s response came in February 1992, when it announced a six-year plan to implement a revised pesticide regulatory system designed to be more accountable, transparent and predictable. Financial resources of $81 million were to come almost entirely from Green Plan funds.

As the first step towards coordinating all the various pest management activities, the government established the Interdepartmental Executive Committee on Pest Management to coordinate the activities of the four departments involved and a Secretariat to oversee implementation of those recommendations of the Review Team to which the government agreed. As mentioned, the Minister of Health assumed responsibility for pest management regulation on 1 April 1995 and continues to liaise with the other key federal departments and develop Memoranda of Understanding to facilitate strong working relationships with them.

The Government of Canada has three main goals for the revised regulatory system:

better protection of health, safety and the environment;

more competitive agriculture and forestry resource sectors; and

a more open and efficient regulatory process.

The risk posed by a new product is evaluated by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency according to data submitted by applicants. The PMRA introduced a cost-recovery scheme in 1996-97, and farmers are starting to voice concern about how the mandatory fee payments will affect the purchase of low-use agricultural pesticides and international competitiveness. The Memorandum of Understanding and Action Plan signed in 1998 by Canada and the United States include provisions on harmonization of regulations for the approval and use of pesticides. PMRA officials, in collaboration with their U.S. counterparts, are working on mechanisms that will make it possible to achieve a harmonization process for the approval of pesticides and a joint pesticide approval system. At the second meeting of the North American Market for Pesticides (NAMP), held in Ottawa on 14 April 2000, more than 100 participants from Canada and the United States discussed ways of making the proposed harmonization a reality, as well as the main pesticide-related issues. These participants represented farmers, the pesticide industry, AAFC officials, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the PMRA, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and state and provincial governments.

B. Biotechnology and New Crops

Although the term “biotechnology” is widely used, there is considerable confusion about what it means. According to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), the term refers to the application of science and engineering to the direct use of living organisms, or parts or products of living organisms, in their natural or modified forms. The development of new crop varieties by traditional cross-breeding is a biotechnological process, as is the brewing of beer through fermentation.

Recombinant-DNA (rDNA) technology is the most recent advance in this area. Known as “genetic engineering,” it involves the application of molecular biochemical techniques to develop new varieties or organisms, including micro-organisms, crop plants, and animals. Although traditional cross-breeding techniques allow genetic combinations within the same, or closely related species, rDNA techniques permit the transfer of genes across species boundaries; this is a more controversial adaptation.

The major federal statutes applicable to products of biotechnology are administered by Health Canada, Environment Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. The Canadian regulatory system as outlined in the 1993 Regulatory Framework regulates the product not the process; the risk-based safety assessments apply to all products, regardless of how they were developed.

Biotechnology offers enormous advantages in virtually all aspects of crop and animal production in the Canadian agricultural sector. In August 1996, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada published regulations covering the production of new crop varieties created using rDNA technology, biofertilizers, biofeeds, and veterinary biologics.

Given the potential for organisms such as plants to spread and transfer genetic material inadvertently to non-target species, the regulatory process attempts to assess potential outcomes carefully before any modified organisms and plants are released into the environment.

Some modified organisms or plants have already been approved and made available to consumers; examples are genetically altered tomatoes, canola and soybeans. It is expected that cheese, wine and dairy products might soon be produced using genetically engineered micro-organisms. Although Canada continues to delay introduction of milk produced with recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST), a growth hormone produced through the genetic engineering of bacteria, this hormone was approved for use in the United States in February 1994. Faced with market reluctance and the fear displayed by many farmers, the Canadian Wheat Board issued a position statement on transgenic grains, particularly wheat, in April 2001.(15) The CWB is consulting with the federal government and the industry to ensure that market acceptance issues will be a required consideration in the process of registering any variety of transgenic wheat.

“Functional foods” – another category of designer foods coming to supermarket shelves – have had elements added to enhance their ability to fight a specific disease. The products tend to blur the line between foods and drugs and consequently pose a problem for Health Canada, which does not allow food products to make medical claims. On 15 June 2001, Health Canada announced the final phase of consultations in the framework of the regulations governing nutritional labelling. At issue is improved nutritional labelling for pre-packaged foods, and in particular rules for nutrient-level claims and health claims. The regulations could be adopted by late 2001 or early 2002.

Farmers are starting to wonder about their future role with respect to food, because these new technologies will be controlled by private companies that determine what crops to grow, how to grow them, and the products that will be applied to them. Small “resistance” groups are already forming in both the industrialized and developing countries, to defend farmers’ “right to produce.”

1876 - First shipment of prairie wheat to Eastern Canada.

1891 - Winnipeg Grain and Produce Exchange incorporated.

1892 - Development of Marquis wheat at Agriculture Canada’s Central Experimental Farm.

1904 - Beginning of futures trading at the Winnipeg Exchange.

1905 to 1910 - Farmers developed elevator companies. The Grain Growers’ Grain Company, the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company and the Alberta Farmers’ Co-operative Elevator Company were created.

1912 - The Canada Grain Act was passed, establishing the Canadian Grain Commission which focused on grain quality. New grain varieties must be equal or better than those existing and must be visually distinguishable.

1917 - United Grain Growers was constituted.

1917 to 1919 - Because of World War I, the Winnipeg Exchange was closed and the government centralized grain buying and guaranteed a price for domestic and export sales. This prompted producers to think about a more centralized selling agency.

1919 - A board was established specifically to market the 1919 wheat crop.

Early 1920s - Although the government had viewed the board solely as a wartime measure, farmers called for the re-establishment of the marketing agency. The Central Selling Agency (CSA) was created by three growers’ elevator companies that put together their resources and contacts overseas to sell wheat directly to foreign customers. An initial payout was financed through bank loans, and any surpluses were paid as a final payment.

- The three pool elevator companies were established.

Early 1930s - The CSA, operated by co-ops, marketed half of the wheat production but when wheat prices collapsed in 1929, the provinces underwrote the CSA. Further losses in 1930 forced the federal government’s intervention. The 1928-1930 crops were not liquidated until 1935.

1933 - First International Wheat Agreement established a minimum price and export quotas, but the agreement did not last.

1935 - The Canadian Wheat Board Act established a voluntary marketing agency. The Act provided for an initial price and allowed the Canadian Wheat Board to sell grain anywhere in the world at market prices. The Board incurred a loss of $11.9 million in its first year. As a result, the government limited the payment to $0.875 per bushel, only if the market price fell below a $0.90 per bushel level. In other words, the government set a floor price for wheat. During this period, when poor crops kept prices high, farmers shipped their wheat through the open market so that the CWB did not receive much wheat.

1939 - World prices declined below the floor price of $0.90 per bushel level and the CWB – forced to pay the price established by the Act – consequently received the bulk of the crop and faced a loss of $60 million. The government amended the Act to limit purchases to 5,000 bushels per farmer and to reduce the support price.

1940 - WWII prevented grain from being marketed in Europe, which resulted in surpluses and in the need for more storage space. The CWB developed an acreage delivery system.

1942 - The CWB took control of the allocation of railway boxcars.

1943 - The CWB became a monopoly and it became compulsory to market grain through the CWB.

1946 - A contract to deliver 600 million bushels of wheat in four years was signed with the United Kingdom.

1949 - Oats and barley were added to the jurisdiction of the CWB. Eastern users of feed grains were concerned about increasing prices. The Canadian Federation of Agriculture examined the situation, but was unable to find an equitable pricing policy. Eastern users asked for the removal of oats and barley from the CWB.

- The Chorleywood baking test allowed the production of bread with less wheat protein. This had an impact on Canadian hard red spring wheat.

1955 to 1965 - The CWB was able to use access to Crown credit as a marketing tool to make major sales to the central buying agencies of countries such as Japan, China, Russia and Poland.

1967 - Sections of the CWB Act requiring a formal review of the CWB’s legislative powers every five years were repealed.

1970 - To reduce shipping time and enhance marketing operations, the grain industry adopted a block shipping system for car allocation.

- A set-aside program called LIFT (Lower Inventories for Tomorrow) was introduced and was triggered when carryover stocks exceeded 27 million tonnes. The result was immediate; seeded wheat acreage dropped by one-half in that year.

1971 - The two-price wheat policy, which set a floor and a ceiling price for domestic millers, was introduced.

1973 to 1974 - As a result of a new domestic feed grain policy, interprovincial movement of feed grains was allowed and the private sector carried out sales of feed grain. As of the 1974-75 crop year, the CWB only remained in charge of export charges for feed grains.

- The results of a plebiscite conducted by the federal government showed that 53% of farmers favoured an open market system for rapeseed (canola) trading.

- The federal government purchased its first hopper cars to replace the old boxcars.

1976 - The Western Grain Stabilization Program was introduced.

1978 - By changing the fatty acid composition of rapeseed, plant breeders created a new seed called canola.

1979 - The Grain Transportation Agency was created to manage the hopper car fleet.

1980s - Export subsidies allowed Europe to become a major competitor on the world grain market.

- Herbicide-resistant canola was developed.

1983 - The Western Grain Transportation Act (WGTA) was passed and replaced the Crow’s Nest Pass Agreement, which had maintained railway rates at the same levels since the past century.

1985 - With European markets becoming less attractive, Canadian grain exports were targeted to Asia. As a result, Thunder Bay – which had historically handled 70% to 80% of the grain – saw its share decline to 40%.

- The reluctance of the railways to replace the old boxcar fleet, and bottlenecks in grain transportation, forced the federal government – along with the Alberta and Saskatchewan governments – to purchase new steel hopper cars.

- Canola oil received “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) status from the United States Food and Drug Administration. This was the trigger for a booming market for canola oil.

1989 - Oats, accounting for less than one-half of 1% of the CWB’s business, were removed from the CWB’s jurisdiction.

- The Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSTA) was signed by both countries which agreed to remove all tariffs and import restrictions over a ten-year period. However, in the case of wheat and barley it was agreed that border restrictions would be removed when subsidies were equivalent in both countries. End-use certificates were used to prevent mixing of Canadian and U.S. grains. CUSTA also meant the end of the two-price wheat policy and eliminated the WGTA subsidy paid on grain shipped to the U.S. through Vancouver.

- The federal-provincial Agri-Food Policy Review on industry competitiveness was launched.

1990 - The CWB initiated its Review Panel which recommended substantial changes in order to restructure the CWB and make it look more like other international business organizations. However, the Panel concluded that dual marketing and price pooling were incompatible because the CWB would not receive enough volume when grain prices were high.

1991 - Canada implemented two new generations of farm income safety nets – the Gross Revenue Insurance Plan (GRIP) and the Net Income Stabilization Account (NISA) – in order to counter massive grain subsidies in the world market.

1992 - Agriculture Canada’s regulatory review called for increased user fees and less regulation.

- A Round Table on Barley examined the pros and cons of a continental barley market.

- Sales of grain, particularly durum wheat, to the United States created a major irritant between the two countries.

- A farmer-owned co-operative, United Grain Growers (UGG), became a publicly traded company.

1993 - For a short period between 1 August and 10 September, the North American barley market was operational. Barley exports once again became the sole responsibility of the CWB when a court ruled that a continental barley market was illegal under the CWB Act.

- The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed by Canada, the United States and Mexico.

- A Canada-U.S. panel, established under the CUSTA, recommended an audit of Canadian durum exports to the United States.

- Subsidies under the WGTA were cut by 15%.

1994 - The Uruguay Round of the GATT was concluded. All contracting parties agreed to reduce export subsidies by 21% in volume and by 36% in dollar terms, and to reduce domestic support by 20% over a six-year period beginning in 1995.

- On 10 September, Canada and the United States signed an agreement to limit Canadian wheat exports (durum and other varieties) to the U.S. to 1.5 million tonnes for a one-year period. The Agreement also called for the establishment of a Canada-U.S. Joint Commission on Grains (Blue Ribbon) to examine the grain marketing and pricing systems in the two countries with the goal of making recommendations for reducing trade irritants.

- The concept of dual marketing took shape.

1995 - To conform with GATT requirements, the federal government eliminated the WGTA but compensated grain producers with an ex gratia capital payment of $1.6 billion.

- The federal Minister of Agriculture established the Western Grain Marketing Panel (WGMP) with the mandate to examine the complex business of grain marketing in Canada.

- A group of dissident farmers called “Farmers for Justice” crossed the Canada-U.S. border with shipments of grain that did not have proper CWB export permits.

1996 - After 15 “town hall” meetings, 12 days of public hearings in the Prairies, 6 major research projects, and 147 written submissions, the Western Grain Marketing Panel published its report on 9 July.

- The farmer-owned co-operative Saskatchewan Wheat Pool was transformed into a publicly traded company.

- Although it remains non-operational, “dual marketing” became part of the common language of the grain industry.

- On 3 December 1997, the federal government introduced Bill C-72, An Act to amend the Canadian Wheat Board Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts (see Legislative Summary LS-281E).

1997 - In February, Alberta Wheat Pool and Manitoba Pool Elevators launched a hostile and unsuccessful takeover bid for the UGG.

- On 25 March, the results of the producer vote on Prairie barley marketing were published: 37.1% of producers voted for an open market and 62.9% voted for single-desk selling.

- On 16 April, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food reported Bill C-72 to Parliament with amendments, notably to clarify that a majority of ten directors would be elected to the board by producers and that the board would be responsible for designating one director as chairperson. Because Parliament was dissolved for the election of 2 June 1997, it did not have time to examine Bill C-72 further.

- On 25 September, Bill C-4, An Act to amend the Canadian Wheat Board Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, received First Reading in the House of Commons.

- On 7 November, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food reported back the bill to the House of Commons.

1998 - In March and April, the Standing Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry held public hearings in the Prairies.

- On 14 May, the Standing Senate Committee tabled its report in the Senate, which included three major amendments to Bill C-4.

- On 11 June, Bill C-4 received Royal Assent.

- In September, the Canadian Transportation Agency determined that Canadian National Railways had failed to meet its obligations with regard to grain transportation. The CNR and the CWB agreed on $15 million in compensation.

- On 31 December, the new Board of Directors – including ten elected farmers and five members appointed by the government – replaced the former Commissioners.

2000 - The Auditor General of Canada undertook a review of the CWB’s operations.

- The CWB launched a consultation to find an effective means of enabling organic grain producers to market their products.

2001 - In April, the CWB issued a statement of principles on genetically modified (“transgenic”) grain. One of the guiding principles is that market acceptance will constitute a required consideration in the registration process.

Source: Canadian Wheat Board: Internet site and various annual reports.

(1) The statistics cited in this section are taken from World Grain Statistics, published by the International Grains Council.

(2) Canadian Wheat Board statistical tables; International Grains Council, World Grain Statistics.

(3) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, special edition of the bimonthly bulletin on Saskatchewan, Vol. 13, No. 15, Marketing Policy Directorate, Winnipeg, 22 September 2000.

(4) In Ontario, all wheat sold by producers must be marketed by the Ontario Wheat Producers’ Marketing Board (OWPMB), except for farm-to-farm sales of feed and seed wheat. Grain produced in Quebec and the Maritimes is primarily for feed used domestically and is therefore marketed by a large number of different grain companies.

(5) Canada-U.S. relations are examined further in this paper, from different perspectives, in the sections entitled “Canada-U.S. Grain Trade Relations” and “The World Trade Organization, State Trading Enterprises (STEs), and Export Subsidies.”

(6) See Legislative Summary LS-281E, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament.

(7) See Legislative Summary LS-292E, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament.

(8) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Report on Plans and Priorities 2001-02, p. 10.

(9) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Government of Canada Overview Regarding Canada-U.S. Wheat Trade Issues, paper accompanying the news release entitled Canadian Wheat Trade Policies and Practices Consistent with International Trade Obligations,Ottawa, 6 June 2001.

(10) World Trade Organization, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Article XVII, paragraph 1.a.

(11) See the section entitled “Canada-U.S. Grain Trade Relations.”

(12) Canada-U.S. Joint Commission on Grains, Final Report, October 1995, p. 100.

(13) World Trade Organization, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Article XVII, para.1.a.

(14) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada news release entitled Canadian Wheat Trade Policies and Practices Consistent with International Trade Obligations,Ottawa, 6 June 2001.

(15) Canadian Wheat Board, Internet site – publications section, www.cwb.ca.