PRB 01-3E

CANADA AND THE UNITED

STATES:

TRADE, INVESTMENT, INTEGRATION

AND THE FUTURE

Prepared by:

Blayne Haggart

Economics Division

2 April 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

3. Has the FTA Resulted in Tranquility?

1. Canada’s Special Status is in Jeopardy

3. Overdependence on the United States

5. Environmental and Labour Concerns

6. Influence on Domestic Policy

CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES:

TRADE, INVESTMENT, INTEGRATION

AND THE FUTURE

Historically, Canadian policy has wavered between the desire for closer economic ties with the United States, and the desire to maintain a safe distance from the world’s most powerful country. Three elections – in 1891, 1911 and 1988 – were fought on the issue of free trade with the U.S., and even in relatively peaceful economic times, there is no shortage of concerns about perceived threats to Canadian sovereignty from the United States.

While this debate is ongoing, the context in which it takes place is changing rapidly. Over the past decade, Canada’s economic ties to the United States have deepened markedly, first under the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), later expanded to include Mexico under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Elsewhere, economic integration is increasing, both multilaterally under the World Trade Organization (WTO) and regionally through the European Union, the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).

Canada and the United States enjoy one of the closest relationships in the world. Over the years, the United States has been a key ingredient in ensuring Canada’s security and prosperity. Although disagreements and disputes can be found in any relationship, the Canada-U.S. relationship is very secure, as evidenced by the world’s longest undefended border, across which more than $1.5 billion of goods crosses daily.

Because of the importance of the United States to Canada’s well-being, it is important even in tranquil, prosperous times that Canada pay attention to its relationship with its neighbour to the south. Managing this relationship is becoming more complex, for a number of reasons.

First, the world-wide trend toward economic integration is redefining sovereignty and the conditions under which nations can be independent, interdependent and prosperous. This trend has led some policy analysts to call for increased integration with the United States.

Second, guaranteeing access to Canada’s most important market (and the wealthiest country in the world), always an important concern, must be accomplished within the context of a changing United States. The focal point of U.S. power is on the move. Canada has traditionally had a “special relationship” with Washington, founded on the common understanding of leaders and policy-makers who had the same shared experiences of the Great Depression and World War II. However, as the locus of U.S. power shifts from the Northeast to the Southwest, Canada may find it increasingly difficult to be understood by, and plead its case in, Washington.

Third, a new generation of U.S. leaders, exemplified by President George W. Bush, formerly Governor of Texas, is coming into power, for whom Canada is only one of many countries with which the U.S. deals. The focus of the U.S. will increasingly be on a newly vibrant Mexico under President Vicente Fox.

Fourth, traditional concerns about overdependence on the U.S. market for Canada’s economic well-being remain. Worries have also been expressed about NAFTA provisions, such as the investor-state investment rules under Chapter 11; critics worry that these rules erode national power to establish environmental and other regulations. Ironically, the framers of Chapter 11 did not foresee this problem with what was supposed to be a tool to protect Canadian and U.S. investments in Mexico. There is the ever-present concern over protection of Canadian culture in the face of the allure of U.S. cultural products, as evidenced by the dispute over “split-run” magazines in the late 1990s.

Finally, there are the recurring elements that affect any close relationship, related to implementation of the FTA and the NAFTA, and the reality of being a small country located next to the most powerful country in history.

This paper is divided into four parts:

The first part introduces the Canada-U.S. economic relationship.

The second, and key, part examines the state of the trade relationship and the experience under the FTA and the NAFTA, highlighting important issues in a context of increased economic integration.

The third section briefly discusses foreign direct investment.

The paper ends with some concluding remarks.

In academic circles, some are calling for deeper integration with the United States, in the form of a truly common market with full labour mobility, a common commercial policy, tax harmonization, and/or some form of common currency. Meanwhile, under the NAFTA, trade relationships – to take but one example – are turning this vision of increased economic integration into a reality.

Unlike the European Union, which has moved toward integration through the creation of supranational institutions with clear goals and priorities for integration, the Canada-U.S. relationship is relatively less formal and directed. The defence relationship is managed bilaterally under NORAD and multilaterally under NATO. Trade is managed under the FTA and the NAFTA, and a number of other bilateral undertakings deal with additional areas of joint concern. For example, the International Joint Commission has been addressing transboundary water issues (concentrating on the Great Lakes) since 1909.

Integration has been most obvious in the economic sphere, but even here the FTA and the NAFTA “do not establish any permanent overarching supranational institutions, nor do they anticipate how the economic linkage might deepen.”(1) Unlike the European Union, the FTA and the NAFTA are trade agreements, not customs unions. There is no common currency or common external tariff, only limited labour mobility, and each national government continues to make its own policy regarding foreign affairs and large parts of domestic economic policy. Capital, on the other hand, is mobile, and our financial markets are tightly linked. Unlike the situation in Europe, greater economic integration was not pursued as a forerunner to greater political integration.

The increasing calls for greater economic integration come mainly from the Canadian business community, “such as the Business Council on National Issues (BCNI) and John Roth of Nortel, and Canadian think tanks, most notably, the C.D. Howe Institute.”(2) In basic terms, increased integration would allow firms full access to, and the ability to rationalize costs over, a large market.

According to another argument, increased economic integration is needed because the world’s multilateral trading system is moving toward a three-region system: North America (or the Americas); the European Union (EU); and Asia-Pacific, led by Japan. Because Canada’s most important trading partner is the United States, it is vital for Canada to guarantee access to the U.S. market.

This argument is countered by concerns over what this would mean for political sovereignty, and, in the case of the low dollar, the realization that a low dollar both attracts industry, which pays less for labour than in the U.S., and makes Canadian exports competitive abroad.

Even with the low dollar, Canada has been experiencing a net outflow of foreign direct investment. The role of a falling dollar is controversial: although it can protect an industry in the short term, the degree to which it shelters firms from having to undertake productivity reforms can hurt an industry in the long term.

Nowhere can the rise in economic integration between Canada and the United States be seen more than in trade. In many ways, trade sustains the Canadian standard of living. Exports account for approximately 40% of Canadian Gross Domestic Product and, according to the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, one in three jobs is linked to trade.

In Canada’s case, when one talks about international trade, what is really being discussed is trade with the United States. Fully 86% of Canadian exports – worth 33% of GDP – are shipped to the United States. The importance of the United States to Canada’s well-being does not end there. Canada enjoys persistent and significant merchandise trade surpluses with the United States – in 1999 reaching $60.5 billion – that help make up persistent trade deficits with the rest of the world (in 1999 totalling $26.6 billion). This helps explain why, “from the criteria of national interest the U.S. is Canada’s first, second, and third priority.”(3)

Canada-U.S. relations in the economic and political sphere are currently marked by a sense of tranquility and general cooperation. Occasional disagreements over such perennial issues as Cuba and softwood lumber have not seriously dampened the relationship.

Although this relationship is more important for Canada, the U.S. relies to a significant degree on Canada. At 23% of U.S. exports, Canada is the United States’ largest foreign market, higher than the EU, which has almost ten times Canada’s population.

The extent of economic integration between Canada and the United States is even more striking when one examines intra-firm and intra-industry trade levels. Under the FTA, intra-firm and intra-industry trade has risen as companies can now locate production facilities in the most efficient areas across a larger market. In other words, a large part of trade that shows up in Statistics Canada’s international trade statistics is not carried out by independent firms. One estimate holds that “some 70% of our trade is not conducted at arm’s length – about 40% is intrafirm while another 30% is the result of licensing and other inter-corporate relations.”(4) United States corporations dominate intra-firm trade.(5)

A high level of integration exists among firms, which no longer recognize distinct “Canadian” or “American” markets. Intra-industry and intra-firm trade has been particularly evident in the automotive industry, which accounts for more than 30% of Canadian exports to the U.S. and about 25% of U.S. exports to Canada: “This is mostly an incestuous relationship between the same companies which are located on the two sides of the border in close proximity to each other.” Furthermore, “the same trend can be seen in other sectors as well, for example, in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, industrial machinery, food products, and telecommunications equipment.”(6)

While the United States – with its vibrant economy, huge population base and proximity to Canada – has always attracted a large proportion of Canadian trade, the signing of the FTA caused an already close economic relationship to draw even closer.

The Agreement lowered tariffs while instituting rights and obligations covering investment, services, and dispute settlement. The phase-out of tariffs under the FTA was completed on 1 January 1998, although some tariffs remain in place for certain products in Canada’s supply-managed sectors (e.g., dairy and poultry), as well as sugar, dairy, peanuts and cotton in the United States.

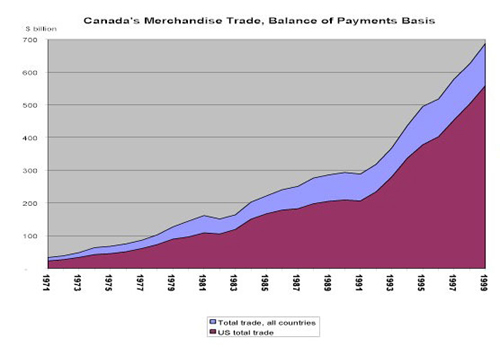

Consequently, between 1989 and 1999, two-way trade between Canada and the United States rose by 167%. Financial-services trade grew at an annual rate of 21%, while computer and information services rose by almost 30%.(7) As would be expected, trade in goods that were liberalized by the FTA grew faster than trade in goods that were unaffected by the FTA. About one-quarter of the total increase in Canada-U.S. trade was “directly attributed to lower tariffs, an amount that implies a very large change in imports in response to a given tariff reduction.”(8)

Canadian merchandise trade with the U.S. accounted for 81% of our total trade in 1999, up from 72% in 1988. Fully 86% of Canada’s merchandise exports were sent to the United States in 1999. This accounted for about 33% of Canada’s GDP, up from under 20% in 1989.

Chart 1

Source: Statistics Canada’s CANSIM database

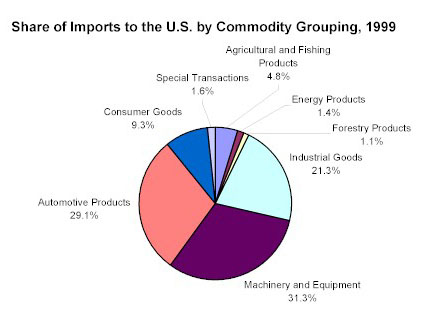

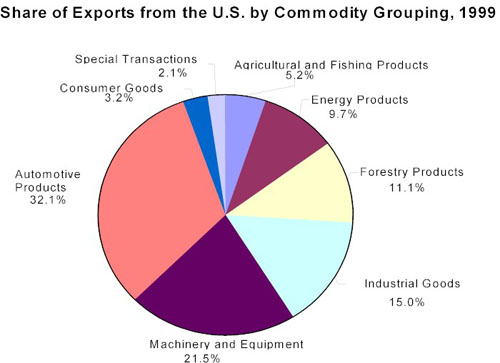

Although the change has not been spectacular, there has been a slight decrease in the proportion of resources exported to the United States. Overall, automotive products are the most frequently traded goods, accounting for 32% of Canada’s exports and 27% of its imports. This is followed by machinery and equipment (22% exported, 29% imported), and industrial goods (17% and 21%). Primary products represent another important category, and clearly illustrate the difference in Canada’s trading profile versus the United States: 26% of Canada’s exports to the U.S. are primary products, against only 8% of its imports.(9)

According to Industry Canada, “non-traditional” exports – such as clothing and textiles, furniture and fixtures, plastics, and “Other Manufacturing” – are growing rapidly. As well, the same report remarks that “for several Canadian industries, the U.S. market is relatively more important than the Canadian market.”(10)

Chart 2

Source: Statistics Canada

Chart 3

Source: Statistics Canada

Although significantly smaller than merchandise trade, Canada’s services exports to the United States have almost tripled since 1989, rising from $11.8 billion in 1989 to $31.1 billion. Services imports from the United States doubled over the same period, rising from $18.1 billion to $36.9 billion. Although the FTA affected services less than goods, those services covered by the Agreement rose more than those not covered by the FTA.(11) The U.S. share of imports and exports has remained relatively constant over this period, with its export share rising from 57% to 60% and its import share holding steady at 63%. Commercial services account for about half of these totals.

Trade with the U.S. has surpassed interprovincial trade in importance. In 1988, interprovincial exports of goods, at $133 billion, were higher than exports to the United States ($101 billion). By 1998, exports to the U.S. ($252 billion) easily outstripped total interprovincial exports ($177 billion). Between 1992 and 1998, interprovincial trade rose by an average of 4.7%, far below the 11.9% growth in international exports.(12)

Table 1: Comparison, interprovincial versus U.S. exports

1988 |

1998 |

|

$ billion (current dollars) |

||

| U.S. Exports | 101 |

252 |

| U.S. Imports | 86 |

203 |

Total |

187 |

455 |

| Interprovincial Exports | 133 |

177 |

| Interprovincial Imports | 133 |

177 |

| Total | 266 |

354 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Interprovincial Trade in Canada, 1992-1998; 1984-1996, Catalogue No. 15-546-XIE; CANSIM database; Canadian International Merchandise Trade, December 1998, Catalogue No. 65-001-XIB. U.S. numbers are current prices, unadjusted; Industry Canada.

Canada is the major trading partner of 37 of the 50 U.S. states. According to Industry Canada, Canadian trade accounts for over 3% of most of the northern U.S. states’ Gross State Product. These are Canada’s most intensive partners (accounting for 63.4% of Canadian exports to the U.S. in 1998, down from 70.1% in 1989), although the quantity of exports being diverted to the U.S. Midwest and South, especially California and Texas, is increasing.(13)

The importance of trade among regions (states and provinces) has increased. “In recent years, trade between the U.S. states bordering Canada and their Canadian counterparts has grown substantially faster than national bilateral trade.”(14) This is not surprising given the reduced impediments to trade under the FTA and the NAFTA and the closeness of Canadian urban centres to the United States. For example, Southern Ontario, from which most of Canada’s trade originates, is within a day’s drive of over 100 million Americans.

Chart 4

Source: Industry Canada, Trade Data Online

Ontario, at almost 60%, accounts for the lion’s share of trade with the United States. It is therefore no surprise that it is by far the most dependent on U.S. trade. Exports to the U.S. accounted for 40% of its GDP in 1998, compared with 20% in 1989. Quebec and Alberta, whose U.S. exports account for a quarter of their GDP, follow Ontario. All provinces posted huge advances in U.S. exports over the 1990-1999 period.

Chart 5

Provincial Share of Exports to U.S., 1999

Source: Industry Canada, Trade Data Online

Table 2: Growth in U.S. merchandise trade, by province and territory

1990 |

1999 |

% change |

|

$ million (current dollars) |

|

||

| Newfoundland | 1,315 |

1,998 |

51.9 |

| Prince Edward Island | 101 |

489 |

381.4 |

| New Brunswick | 2,077 |

5,204 |

150.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 1,515 |

3,144 |

107.5 |

| Quebec | 19,148 |

52,557 |

174.5 |

| Ontario | 60,357 |

182,842 |

202.9 |

| Manitoba | 1,813 |

6,569 |

262.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 2,417 |

5,638 |

133.2 |

| Alberta | 11,510 |

29,360 |

155.1 |

| British Columbia | 7,113 |

20,241 |

184.6 |

| Northwest Territories | 21 |

12 |

-42.6 |

| Yukon | 2 |

18 |

790.1 |

| Nunavut | – |

1 |

– |

| Total U.S. trade | 107,393 |

308,076 |

186.9 |

Source: Industry Canada, Canada’s Growing Economic Relations with the United States, Part 1 – What are the Key Dimensions? 10 September 1999.

The FTA and, to a lesser extent, the NAFTA,(15) the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the agreements handled by the World Trade Organization (WTO), have had a strong impact on trade levels and productivity. This effect can be thought of as having two major components.

First, using the GATT as a jumping-off point, the FTA reduced tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade in “all goods and most services, as well as many investment transactions and most business travel. The most extensive obligations covered trade in goods and included obligations regarding tariffs, rules of origin, quotas, customs procedures, safeguards, unfair trade remedies, government procurement, national treatment, technical barriers, and exceptions.”(16)

Studies have found that these lowered tariff barriers have generally resulted in increased trade: “Other than in automobiles and parts and petroleum, trade between the two countries has grown more quickly in those sectors liberalized by the Canada-US FTA than in those not liberalized.”(17)

However, it is difficult to isolate the impact of an individual trade deal, such as the NAFTA, on a country’s trade and overall economic performance.(18) While there is no doubt that the NAFTA has had its beneficial impacts, one can make a very plausible argument that other factors (e.g., the robust nature of the U.S. economy compared to our own over the 1993-1998 period, the Canadian-U.S. exchange rate, etc.) have been equally if not more influential in causing Canada’s improved trade and economic performance. The recent tremendous surge in economic activity would more than likely have occurred, NAFTA or no NAFTA.

Second, trade has benefited from increased stability that has resulted from the “significant bilateral regime, particularly in the realm of trade and investment, with its own principles, norms, and rules, as well as some institutions,” that have been put in place to deal with and manage this increased trade.(19) These have lowered transaction costs and reduced uncertainty.

Canada-U.S. trade has in particular benefited from the growth in rules-based regimes designed to strengthen free trade among countries, such as the FTA, the NAFTA and the WTO. In particular, the FTA’s (and the NAFTA’s) dispute-settlement mechanism has “greatly strengthened the rule of law in relations between Canada and the United States. … While there may be problems to resolve the day-to-day irritants of the rapidly growing trade and investment flows, Canada has benefited from a more principled approach to resolving conflict.”(20) Other trade disputes are settled at the WTO. This is not to say that there have been no trade irritants – softwood lumber and supply management of the agricultural sector continue to be sore spots – but in a trade relationship as large as that of Canada and the U.S., very few have been so difficult as to require formal dispute settlement.

3. Has the FTA Resulted in Tranquility?

The most common word used to describe Canada-U.S. trade relations (and the rest of the relationship) is “tranquil.” This is partly due to the above-described effects of the FTA. However, the role of the unprecedented decade-long U.S. economic expansion of the 1990s cannot be ignored. In good times, trade irritants are more easily ignored than during recessions. Just as Canada vacillates between greater and more restrained integration with the United States, so the U.S. wavers between internationalism and protectionism/isolationism. Protectionism, and with it trade irritants, always comes to the fore during an economic downturn.

Guaranteeing access to the U.S. market was the raison d’être underlying the FTA. The past decade has been characterized by good economic times which have dampened traditional concerns over trade disputes. It will be instructive to see whether this “tranquil” relationship persists when the economic climate is not so favourable.

A major selling point of the Agreement was that the increased competition of the larger U.S. market would lead to productivity improvements; whether this has in fact happened or is starting to happen is unclear. Among small businesses, one study notes “while one might have expected small Canadian firms to begin growing by closing the productivity gap between themselves and large Canadian and foreign firms, this has not been happening.” One possible explanation for this is that these firms still face barriers to access in the United States. This is backed up by findings that the manufacturing industry has posted productivity gains, especially in industries where tariff barriers had previously been high.(21) Another economist, Daniel Trefler, in hearings on productivity held by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, reported that the FTA did enhance the productivity of those sectors that saw their tariff protection reduced. According to the resulting report, “He believes that the FTA caused those sectors to see an increase in productivity growth of one-half of one percent per year. This he thinks is a significant amount.”(22)

Regardless, Canada has not experienced a convergence in productivity rates with the United States, whose productivity growth has outstripped Canada’s, although it seems that productivity increases were most significant in those industries most affected by the FTA.

Initial hopes for the FTA were high: “Prior to the FTA, studies had concluded that Canadians would see a rise in their standard of living as a result of tariff elimination between Canada and the United States.”(23) However, despite the promises of increased prosperity that would stem from a free-trade agreement, Canadian income and employment levels have not kept pace with U.S. levels: “Living standards, in terms of real personal disposable income per person, have declined by 5% over the past decade, whereas America’s have risen by 12%; and Canada’s share of the world’s foreign direct investment has fallen from 6.5% to 4%.”(24) As would be expected by an economy undergoing a period of restructuring, Canada lost over 15% of its manufacturing employment, following the signing of the FTA (1989-1992).

The role of free trade in affecting income and employment is unclear. Many economists attribute at least part of the decline in wages and rise in unemployment to the recession of the early 1990s. According to Nobel laureate economist Robert Mundell (and echoed by other economists), the Bank of Canada’s tight, zero-inflation monetary policy of the late 1980s and early 1990s kept interest rates high, depressing growth and exacerbating unemployment: “By and large, the Canadian public has never understood this episode in its history, and the newly-formed Free Trade Area unfairly got much of the blame.”(25)

Economist Daniel Schwanen concluded that although the FTA cannot be blamed for a loss of jobs, it has delivered fewer jobs than promised. Other factors, such as the implementation of new technology and the domestic economic situation, have also played an important role in job creation.(26) As economist John McCallum summarizes the research,

Although this debate seems unresolved, it is very likely that there were some transitional job losses as tariffs fell, in some cases from more than 20% to zero in the short space of a decade. On the other hand, jobs were undoubtedly created by the FTA-induced export expansion, although credit for the export boom has to be shared with our depreciating dollar and other forces. Overall, I don’t think that we know whether the FTA led to a rise or a fall in total jobs.(27)

Looking toward the future, there are many issues that any discussion of further economic integration will have to take into account. These include NAFTA implementation problems, and geopolitical concerns such as the ascendance of Mexico and the potential loss of the Canada-U.S. “special relationship.” Some of these are discussed below.

The FTA and the NAFTA also promised increased productivity, lower prices and higher incomes. The extent to which they were able to deliver on these promises should also be considered when examining further economic integration.

1. Canada’s Special Status is in Jeopardy

Despite attempts to lock up access to the U.S. market through the FTA, Canada remains vulnerable to its much-larger trading partner. This, in large part, is simply the reality of being a small country located next to the largest economic superpower in history. To take but one example, half of Ontario’s GDP is now dependent on exports to the United States. Despite the FTA, Canada would be hurt by a more protectionist United States, which would likely exacerbate trade disputes between the two countries.

Traditionally, Canada has had a special relationship with the United States. This was shaped by several factors: the common experiences of the Great Depression and World War II; the fact that the locus of power in the U.S. was adjacent to Canada in the Northeast; and the mutual reliance on each other during the Cold War, through NATO and especially NORAD. In short, despite the stereotypical ignorance of Canada that characterizes Canadians’ perceptions of Americans, Americans (at least Americans in power) knew Canada, and did not think of it as simply another country.

However, as the Great Depression and the WWII generation fades from the scene, and the Cold War into history, this special relationship is also threatened. Furthermore, the centre of U.S. politics is shifting from the northeast to the South and the southwest. With less of a shared experience and a reduced (if not eliminated) need to depend on Canada to defend U.S. soil from a Russian missile attack over the North Pole, Washington increasingly tends to treat Canada as a nation just like the others.

For example, only some last-minute lobbying exempted Canada’s defence industry from being subjected to the U.S. International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) rules, which would have limited Canadian companies’ access to U.S. military procurement contracts, worth $5 billion annually to Canada. Even now, the ITAR exemption has yet to provide concrete results, and may prove to be of short duration.(28)

Canada and the United States share the world’s largest undefended border. Illegal immigration continues to be at the top of the United States’ domestic agenda. Although illegal immigration is a relatively larger problem for the U.S.-Mexico border – the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services has 8,000 agents along the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border, compared with only 300 agents along the 8,895 km (5,000 mile) Canada-U.S. border(29) – high levels of cross-border activity, heightened security concerns, and the desire to treat Mexico and Canada equally (the loss of the “special relationship”) is making border crossing an increasingly important issue.

A 1996 U.S. border regulation intended to reduce illegal immigration from Mexico initially contained no exemption for the Canadian border, potentially “strangling trade and limiting access.” “To politicians anxious to close the border against Mexicans, there is a pleasing symmetry in equal treatment for Canadians.”(30)

Canada has responded to these concerns. The February 2000 budget allocated increased funds for border surveillance; further, Bill C-16 was designed to tighten controls on illegal immigration. It died on the Order Paper when the November 2000 federal election was called. Both governments continue to collaborate on border issues, for instance, through the Canada-United States Partnership (CUSP), a binational forum of customs, immigration and law-enforcement officials.

This last example demonstrates how, in trade, security and generally, Canada is increasingly seen as just another nation. It also – and perhaps more importantly – signals the increased importance of Mexico in U.S. eyes. The signing of the NAFTA has accelerated this tendency to focus on the South and on the U.S. relationship with Mexico.

The numbers suggest a strong reason for this change in emphasis. Mexico’s rapidly growing economy is home to more than 100 million people – over three times the size of Canada’s population – and Spanish is rapidly becoming the U.S.’s unofficial second language. Beyond the numbers, Mexico’s election of businessman Vicente Fox as president, breaking seven decades of autocratic rule, has the potential to improve the Mexican democratic and business environment while capturing the U.S. imagination. Furthermore, the election of Texas Governor George W. Bush as U.S. President has the potential to further concentrate American sights south.

Under the NAFTA, Mexico has gained an increasing share of North American trade, rising from 7% in 1990 to just under 13% in 1999. For Mexico as for Canada, the United States has become the overwhelmingly important market – the destination for almost 90% of its exports.(31) Mexico’s economic renaissance will provide greater competition for Canadian companies exporting to the United States.

As the Canada-U.S. special relationship continues to erode, it will become more difficult to get special exemptions from Congress and the U.S. administration and to keep previously minor problems from becoming major ones. As Christopher Sands puts it, “Without the Canada-friendly bias in U.S. Canada policy provided by the former societal consensus, integration will continue to deepen and Canadian interests will increasingly become subject to the direct and indirect consequences of U.S. policy-making at various levels.”(32)

The possibility of increased misunderstandings heralds the need for Canada to provide high-quality information to all parts of the U.S. political system – including Congress and the individual states – to understand Canada and Canadian-U.S. interests, for example, explaining why the Canada-U.S. border is not the same as the U.S.-Mexico border.

Environmentalists are concerned about the use of NAFTA’s Chapter 11 to rewrite domestic environmental law. Indeed, the investment clause under Chapter 11 of the NAFTA has become one of the most controversial parts of the deal. It was originally drawn up to protect corporations and investors from arbitrary regulation and back-door trade protectionism, particularly as they would affect their investments in Mexico. The Chapter is designed to give firms the right to sue governments if decisions are made that unfairly damage the firms’ business interests.

The provisions mean that foreign investors cannot be made to comply with more stringent rules than apply to domestic companies; they are also entitled to compensation if their property is expropriated. However, what started out as a defence mechanism for investors against foreign governments seems to have become an aggressive tool in the hands of certain corporations to challenge the right of government to introduce regulations.

Critics charge that Chapter 11 undermines Canada’s capacity to protect health and the environment. In the 1998 case of Ethyl Corporation versus Canada, which centred on restrictions on the interprovincial and international trade of MMT, a gasoline additive suspected of being linked to nervous disorders (and which automakers contend reduces vehicle performance), “the Canadian measures fell well short of the standards set in the agreement.”(33) The case was settled out of court. A U.S.-Mexican case regarding environmental regulations was thrown out as frivolous, setting the bar high in dealing with alleged harm caused by governments regulating in the normal course of events.

Ethyl Corporation’s success was followed quickly by other suits. Two days after the announcement of the out-of-court settlement between Ethyl Corporation and the Government of Canada, Ohio-based S.D. Myers Inc. gave notice that it was launching a challenge under Chapter 11 of the NAFTA because of the federal ban on the export of PCBs in 1995 and 1996. In November 2000, the international tribunal appointed to hear the Chapter 11 case found in favour of S.D. Myers.

Three other corporations are also using Chapter 11 of the NAFTA to sue the Canadian government for damages.

Sun Belt Water Inc. of California is claiming $220 million in damages as a result of a ban on water exports from British Columbia.

Pope and Talbot Inc., an Oregon-based forest products company, is claiming $US 30 million in damages under the NAFTA stemming from the softwood lumber agreement between Canada and the United States.

United Parcel Services has filed a minimum $160 million claim for damages caused by Canadian government support of Canada Post.

Chapter 11 does not prevent a government from passing regulations that are genuinely designed to protect health and the environment, although it also allows tribunals to consider only a very narrow spectrum of concerns in its making its decisions. Even so, the federal government decided to attempt to delineate more clearly the scope of the investor-state provisions. In 1998, Canada asked the U.S. and Mexico to re-examine Chapter 11. Specifically, Canada sought an interpretative note to the investor-state clause, which would help narrow the interpretation of what cases could be brought under this Chapter, thereby ensuring that government’s ability to legislate and regulate in the public interest is protected.

The three NAFTA governments continue to be stalled over a possible reinterpretation of the expropriation clause, with Canada’s efforts coming up against Mexican resistance. It is ironic that, although the investor protections were introduced largely to satisfy concerns about doing business in Mexico, that country now appears to be the stumbling block to refining investor rights. Mexico is reluctant to change the provisions because it does not want to alienate potential foreign investors for whom the strict Chapter 11 provisions act as a signal that Mexico will treat investors fairly and favourably.

In a related development, the Canadian and U.S. governments seem to be trying to inject environmental concerns into the Chapter 11 process. Both governments are supporting the bid by Winnipeg-based International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) for intervenor status at a hearing into Vancouver-based Methanex Corp.’s $1-billion suit against the U.S. government over California’s plan to ban by 2002 its controversial methanol-based gas additive MTBE.(34) Mexico opposes IISD’s participation.

3. Overdependence on the United States

Regardless of how one breaks down the numbers, Canada depends to a large degree on the U.S. economy. This dependence revisits traditional Canadian concerns about overdependence on the U.S. market and its effect on the economy and Canadian unity. On the first point, although Canada benefits from a strong U.S. economy, a U.S. recession would hit Canada particularly hard.

Firms are increasingly seeing not two separate national markets, but one market, regardless of the border. This point of view is supported by: Ontario’s high level of integration with the U.S. market; the overshadowing of interprovincial trade by Canada-U.S. trade; and the increasing degree of intra-firm and intra-industry trade.

Canada-U.S. trade exposes the reality that Canada is not a global trader: Canada’s experience with globalization is largely limited to its experience with economic integration with the United States.

This is not to suggest that Canada should ignore the U.S. market while attempting trade diversification, or push for trade diversification at the expense of the Canada-U.S. relationship. It only makes sense to take advantage of our proximity to the large U.S. market. Furthermore, the alternative is unclear. In hearings in Spring 2000, the House of Commons Sub-Committee on Trade, Trade Disputes and Investment heard that many Canadian companies use experience gained by dealing with the (relatively) friendly and familiar U.S. market to expand overseas to the European Union (EU), Japan and other markets.

To the extent that Canadian companies concentrate on the U.S. market, they may be missing out on faster-growing emerging markets, as well as already mature markets such as the EU and Japan, which could, not inconceivably, rise to challenge the economic supremacy of the United States. However, the size of Canada’s relationship with the United States makes it very unlikely that trade diversification will substantially challenge Canada’s U.S. trade in the foreseeable future.

The dispute-settling mechanisms under the FTA and later the NAFTA have helped reduce some of the tensions around trade disputes, although it has not eliminated them– disputes are a fact of life in any trading relationship. Canada is continuing to push for greater cooperation in the use of trade remedy measures (e.g., anti-dumping, countervail) in North America. Under the FTA and the NAFTA, binational panels issue binding rulings on whether anti-dumping or countervail penalties have been correctly applied. However, the NAFTA did not satisfactorily address these issues (including enforcement, delays, a lack of ability to set precedents, and the U.S. tendency to ignore international trade rules when they contradict national interests(35)), and a number of antidumping and countervail cases have been launched.

While reducing some of the tensions, in one sense, the FTA and the NAFTA have failed to depoliticize and regularize disputes: “a crucial problem is that disputes may still be addressed through traditional diplomatic channels, the United States using whatever strategy best suits its interests, with a disregard for NAFTA provisions.”(36) These actions do not seem consistent with the growth of free trade, and there is room for progress. The real question to consider, however, is whether or not the U.S. will agree to proposals for change.

5. Environmental and Labour Concerns

As a trade agreement, the FTA deals with trade issues exclusively, and not with social, labour and environmental considerations. Moreover, much of the agreement’s text establishes rights for commercial actors, but for no one else. This is in contrast to the setup of the European Union, which as a customs union provides much greater political integration and deals with these issues. For instance, the EU has “a regional development fund both to offset negative effects of the common market on specific regions and to allow the relatively less-developed regions to compete on a more even plane,” and EU-wide laws which are binding unless countries opt out.(37)

The FTA and the NAFTA are trade agreements and not customs unions. Consequently, the areas mentioned above are mostly left to the respective nations. However, the NAFTA does have an element of commonality in labour and environmental regulation. Negotiated and implemented in parallel to the NAFTA, the North American Agreements on Labour and Environmental Cooperation were designed to facilitate greater cooperation between the partner countries in those areas and to promote the effective enforcement of each country’s laws and regulations. The Environmental and Labour Commissions charged with implementing these agreements have very limited powers to enforce the agreements.

The jury is still out on the effectiveness of both commissions. Although they are designed to address issues often ignored when dealing with economic integration, they are often slow and ineffective from an enforcement point of view. Both are, without question, subordinate to the main trade agreement, whose principles are binding.

Canada and the United States also have an environmental relationship outside the NAFTA, which usually allows them to settle disputes eventually. In a review of Canada-U.S. environmental relations, Alan M. Schwartz concludes that the two countries have worked well together to address common environmental issues. He cites the example of the International Joint Commission, in operation since 1909, which is responsible for common watersheds and which has been remarkably effective. Other issues that have been addressed in other fora, he adds, include acid rain and management of the pacific salmon stocks.(38)

There also seem to be further moves in the U.S. toward incorporating labour and environmental standards into trade agreements. In December, then U.S. President Bill Clinton announced the launch of free-trade negotiations with Chile. The proposed accord includes “controversial provisions regarding workers’ rights and environmental protection.” This came on the heels of a U.S.-Jordan free trade agreement that “for the first time incorporated labour and environmental standards in the text of a trade agreement.”(39) However, it remains to be seen how a change in U.S. administration will affect this stance, and what it means for the NAFTA and WTO.

Labour is affected by Canada-U.S. economic integration in the same way as it is affected by the internationalization of production in general. Although capital and technology are internationally mobile, labour is not (though it is in the EU).(40) Protecting workers from dislocation that occurs as the result of trade liberalization can sometimes conflict with trade promotion. Two possible solutions to this involve:

international agreements on the treatment of labour (foreshadowed perhaps in the NAFTA side agreement); and/or

using government programs to encourage firms to develop support structures that are not tied to any specific jobs or industries.

6. Influence on Domestic Policy

At its heart, debate over labour and the environment and trade is a debate about the linkages between trade and social policy, and between economic and political integration. One side argues that greater economic integration will lead to the dissolution of Canada; the other side claims there is little connection between the economic and political and cultural spheres.

The extent to which domestic policies are affected by economic integration remains an open question. Convergence seems more likely in some areas than others. For instance, taxes affecting highly mobile factors of production, such as capital and well-educated labour, will be under greater pressure to converge. According to Gary C. Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott of the Washington, D.C.-based Institute of International Economics in a paper written for Industry Canada, integration will also entail greater labour flexibility: “Unions that limit workforce flexibility (in terms of job assignments, layoffs and seniority rules) will be a major negative force” in attracting firms to an area.(41)

The evidence suggests, they argue, that countries can form independent tax policy supporting a socially activist government. They cite the example of the Benelux countries and Germany, both of which have widely divergent tax structures and a high degree of economic integration: “In short, the smaller partners were able to carry on with a more extensive social agenda than the largest partner.”(42)

Indeed, providing quality social services – good public schools, an educated workforce, a clean environment, safe streets and a vibrant culture – can help attract both firms and workers to an area or a country.

Still, as the two economies become more integrated, there is likely to be an increase in disputes over differing regulatory regimes. Such conflict could centre on “local content rules to promote cultural identity or safety regulations for consumer products.”(43) Such a conflict has already been foreshadowed in U.S. challenges to Canada’s supply management of agriculture, and banning of split-run publications.

As Julie A. Soloway, Research Fellow with the University of Toronto’s Centre for International Studies, remarks, the increasing influence of the international trade and investment system – which is not directly accountable to the domestic population – can challenge the legitimacy of domestic law if it is seen to render moot domestic law. “Failure to manage this interface is dangerous because of the risk that ‘the domestic consensus in favour of open markets will ultimately erode to the point where a generalized resurgence of protectionism becomes a serious possibility?’ ”(44) This is a problem for all trade agreements, and probably requires increased transparency and public input into such agreements.

Movement in any way towards further integration with the United States has always been greeted with concerns about its effect on sovereignty. When Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals proposed a free trade agreement with the United States in the 1891 election, the Conservatives suggested such an agreement was simply a prelude to annexation by the United States (the Conservatives won the election). Today, the same argument holds that increased north-south linkages are weakening the east-west axis upon which the country was founded.

It is unclear what the eclipsing of interprovincial trade by Canada-U.S. trade and the integration of Ontario into the U.S. market will mean for sovereignty. The fear is that this will result in a series of “autonomous” regions – especially Ontario – closer to the U.S. than to each other. Queen’s University economist Thomas Courchene believes we are witnessing the rise of “region-states,” where regions trade mostly within their own area. In Ontario, it is evidenced by the high degree of cross-border trade and integration. It therefore reacts to the economic and fiscal policies of its neighbouring states. Because of this increase of trade with the rest of the world at the expense of trade with Canada, “it is increasingly appropriate to view Canada not as a single east-west economy but rather as a series of north-south (cross-border) regional economies. This has dramatic implications, one of which is how to mount our east-west transfer system over an increasingly north-south regional economy.”(45)

There is some evidence to suggest that statistics are exaggerating the U.S. pull and its consequences for sovereignty. To the extent that north-south trade has improved Canadian well-being, increased prosperity should make Canada stronger. Furthermore, east-west trade remains significant. For small businesses, according to the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, “interprovincial trade (and not the sometimes more geographically intuitive north-south pattern) remains a particularly important expansion platform.”(46)

Although the introduction of the FTA and the NAFTA has led to increased trade with the United States, interprovincial trade remains strong, when one considers the size and proximity of the U.S. market. As one study put it, “despite the exceptionally strong pull of geography, there is still a very powerful bias in economic transactions in favour of trading with fellow Canadians. … Because of the exceptionally strong pull of geography, one-third of gross domestic product is tied up with trade with Americans.”(47)

The treatment of culture is also bound to continue as a perennial trade concern, stemming from fundamental differences in perception.

Unique among countries, the United States treats culture like a commodity and is therefore concerned about trade barriers, while Canada’s policy is one concerned with cultural identity. In the United States, culture is the equivalent (basically) to entertainment, and is a good that is properly allocated by the market. In Canada (as in many European nations), culture is an expression of national identity and as such is to be promoted and protected as a public responsibility. To the degree to which culture for Americans is about the profit-making entertainment industry and for Canadians about the politics of national identity, there should be little doubt about the potential for mutual misunderstanding concerning any exempt status for cultural industries in free-trade arguments.(48)

Although culture is exempt from the NAFTA, it is not under the WTO. Using the WTO, the United States won a decision against Canada’s banning of “split-run” magazines; the WTO ruled that magazines were a good, not a service.

However, the “culture wars” are not all one-sided. Although U.S. cultural products continue to dominate Canadian film and television screens, bookstores, airwaves, music shops and magazine stands, Canada has witnessed a “small yet growing volume of cultural goods and services to U.S. markets.”(49) Furthermore, cultural protection is not always an unambiguous matter of reserving a space for Canadians to tell their stories: improved competition – from whatever source – can increase the number of outlets that Canadian artists can use to reach an audience.

Other parts of the treaty have also caused problems. The amount of diversification caused by the FTA remains a point of disagreement. Critics of the FTA point out that over 20% of the increase in trade is concentrated in automobiles, and that the Canadian economy has failed to diversify since the implementation of the FTA.(50) Although dependence on natural resource exports has diminished somewhat, there has been “substantial relative growth” in end-product exports, mostly in the auto industry, with some improvements occurring in a variety of technology-intensive sectors.(51)

Because the NAFTA is a trade and not a customs agreement, it does not provide for the free movement of labour across borders, although it does allow certain classes of workers – such as technology workers and businesspeople – to work more easily in the other country. Although it might be desirable to open the borders among the NAFTA partners to allow labour to cross as easily as capital and goods, any such move is likely to be met with strong resistance from the United States, where officials are concerned about terrorism, the movement of illegal drugs, and of the huge influx of Mexican workers that would result from such a move.

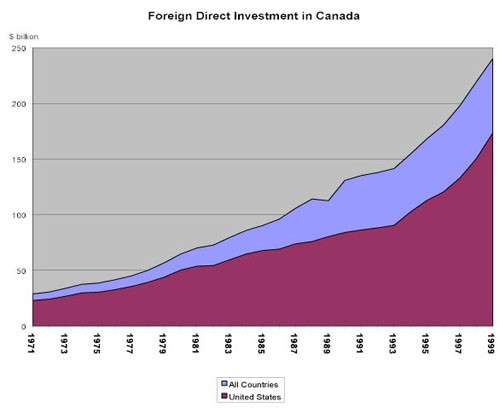

In addition to trade, the FTA (and the NAFTA) greatly liberalized investment flows between Canada and the United States. It provides national treatment of U.S. investors while excluding investment from certain sensitive sectors, retaining government investment review mechanisms, and prohibiting certain performance requirements attached to investments.(52)

The FTA and the NAFTA have seen an increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) among NAFTA partners. The U.S. continues to be the largest foreign investor in Canada, with the majority of this investment “taking the form of acquisitions rather than the establishment of new businesses” and tilting toward technology-intensive industries.(53) At the end of 1999, the total stock of U.S. FDI in Canada was $173 billion, up from $80 billion in 1988. The manufacturing industry attracted about half of the total, followed by finance (other than banking), insurance and real estate (21%), and petroleum (12%). Canada is also the second-largest recipient of total U.S. FDI (11%), behind only the UK.

Chart 6

Source: Statistics Canada’s CANSIM database and Catalogue 67-002-XIB, Canada’s International Investment Position

Chart 7

Source: Statistics Canada’s CANSIM database and Catalogue 67-002-XIB, Canada’s International Investment Position

Along with this increase in FDI in Canada, Canadian investment abroad, traditionally small, has risen to near-parity with FDI in Canada. However, the proportion of Canadian FDI destined for non-U.S. countries has been rising, as the FTA makes it more feasible to service the U.S. market from home.

Despite these changes, the U.S. share of foreign direct investment in Canada has not risen to match trade gains, standing at 72% in 1999, down from 75% in 1985, and far below the high of 82% in 1966. One likely explanation for this is that firms, no longer facing trade barriers, are investing at the most efficient sites. The increased integration wrought by the FTA and the NAFTA has subtly changed the interaction between trade and investment. When faced with tariff barriers, firms undertake FDI to get around these barriers and serve the domestic market.

In a situation where companies can locate wherever they want, this consideration disappears. As a result,

much of Canada’s exports are driven by US direct investment in Canada, and increasingly by Canada’s direct investment in the United States. This is ‘foreign’ investment by official definition, but in reality, once Canada’s branch-plant mentality was discarded under the FTA, investment today is now increasingly predicated on the existence of a large North American market.(54)

Canada is the fifth-largest source of foreign direct investment in the U.S. market. The amount Canada invests in the U.S. – at $134 billion in 1999, it is the destination for 52% of Canadian FDI – is far out of proportion to what the size of our economy would dictate. Some 35% of Canadian direct investment in the U.S. goes to manufacturing, followed by insurance (11%), other finance (10%), and banking (3%).

These increases are taking place against a worrying background. Canada’s share of total world FDI has dropped considerably over the past decade. As a result of the FTA, Canada was supposed to be able to sell itself as an attractive place for countries to base themselves in order to access the world market. Canada’s declining share of world FDI suggests this is not happening. Canada may not be attractive enough to foreign investors because of the following three reasons:

the domestic atmosphere;

access barriers to the U.S. market; or

in times of uncertainty, the U.S. is seen as the only “safe” economy in the world.

John McCallum, in his evaluation of ten years with the FTA, tentatively concludes that FDI has not declined as a result of the FTA, although there is cause for worry. Theoretically, he says,

the impact could go either way. On the one hand, the dismantlement of the tariff wall set up by John A. Macdonald in 1879 allows American and other firms to supply the Canadian market from outside Canada. The lowering of these barriers makes the argument for attracting FDI less compelling.

On the other hand, the FTA allows Canadian-based firms to serve the entire North American market, and, given our lower costs in every industry [according to KPMG (1999)], this should favour more FDI into Canada… the inward stock of FDI has both increased relative to GDP and declined less abruptly relative to the world stock than was the case during the 1980s.

[His main concern] is that, as the Canada-U.S. border comes down in economic terms, our deficiencies in terms of tax regime and non-appearance on the radar screens of multinational companies could exact a mounting toll. Canada’s desire to become a favoured location for both domestic and foreign investors to serve the North American market could also be thwarted by the continuation of Canada-U.S. border impediments.(55)

This paper has outlined the general shape of the Canada-U.S. economic relationship, while speculating on how it will probably develop. Although economic integration between the two countries is likely to continue, it will do so in a context of regional and international economic integration.

On the regional level, economic integration will probably continue by an expansion of the NAFTA to include Chile (with whom Canada already has a free-trade agreement and the U.S. has begun negotiating one) and other countries, and the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas, which would include every country in the Americas except Cuba. The NAFTA countries, especially the United States, would dominate any such area, as they account for 85% of all hemispheric output.(56) On the international front, the WTO will continue to have an impact on the Canada-U.S. economic relationship, as evidenced by its decision restricting Canada’s ban on split-run magazines.

Managing the Canada-U.S. relationship involves working on all these levels. At the moment, the relationship is tranquil, the consequence of close relations and good economic times. However, past experience (gained from living in the shadow of a giant), and the changing context that is eroding the “special relationship,” argue for continued vigilance. As for the shape of future economic integration, one thing that most students of Canada-U.S. relations can agree on is that even though a regime (or level of integration) may be appropriate for any given time, this does not preclude the possibility that it should be changed when conditions change.

The American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer 2000. Devoted to the state of Canada-U.S. relations.

Hoberg, George. “Canada and North American integration.” Canadian Public Policy, August 2000, pp. S35-S50.

Hufbauer, Gary C. and Jeffrey J. Schott. North American Economic Integration: 25 Years Backward and Forward. Ottawa: Industry Canada, November 1998.

Industry Canada. Canada’s Growing Economic Relations with the United States. “Part 1 – What are the Key Dimensions?" 10 September 1999; “Part 2 – Maximizing our Opportunities.” 8 December 1999.

Molot, Maureen Appel and Fen Osler Hampson (Ed.). Vanishing Borders: Canada Among Nations 2000. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Britton, John N.H. “Is the Impact of the North American Trade Agreements Zero?” Canadian Journal of Regional Sciences. Summer 1998.

Canada-U.S. Relations (Canadian Government website with general information).

Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

The NAFTA at Five Years: A Partnership at Work. April 1999.

Opening Doors to the World: Canada’s International Market Access Priorities 2000. Chapter 4: Opening Doors to the Americas.

Hufbauer, Gary C. NAFTA In A Skeptical Age: The Way Forward. Institute for International Economics. July 2000.

Hunter, Todd. “The Impact of FTA/NAFTA on Canada: What Does the Recent Literature Say?” Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, December 1998. Reference Document No. 6.

McCallum, John. “Two Cheers for the FTA.” Free Trade @ 10: A Royal Bank Impact Study. Toronto: Royal Bank, 1999.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Government website devoted to the NAFTA.

The North American Agreements on Labour and Environmental Cooperation are available on the NAFTA website, as are links to the Environmental and Labour Commissions.

Carr, Barry. “Globalization from below: Labour internationalism under NAFTA.” International Social Science Journal 51:1, March 1999, pp. 49-60.

“A greener, or browner, Mexico?” The Economist, 7 August 1999, pp. 26-27.

(1) Fen Osler Hampson and Maureen Appel Molot, “Does the 49th Parallel Matter Any More?” Vanishing Borders: Canada Among Nations 2000, ed. Maureen Appel Molot and Fen Osler Hampson, Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 3.

(2) Andrew F. Cooper, “Waiting at the Perimeter: Making US Policy in Canada,” Vanishing Borders, pp. 39-40.

(3) Cooper, p. 27.

(4) Michael Hart, What’s Next: Canada, the Global Economy and the New Trade Policy, Ottawa: Centre for Trade Policy and Law, 1994, p. 20.

(5) John N.H. Britton, “Is the Impact of the North American Trade Agreements Zero?” Canadian Journal of Regional Sciences, Summer 1998, p. 189.

(6) Hampson and Molot, p. 8.

(7) Gary C. Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, North American Economic Integration: 25 Years Backward and Forward, Industry Canada, November 1998, p. v.

(8) John McCallum, “Two Cheers for the FTA,” Royal Bank, 1999.

(9) Hampson and Molot, p. 4, and Statistics Canada data.

(10) Industry Canada, Canada’s Growing Economic Relations with the United States, Part 1 – What Are the Key Dimensions?, 10 September 1999, p. 25.

(11) Marcel Côté, “Is Free Trade Good for Canada? Ten Years Later the Balance is Positive,” Cité Libre 26, April-May 1998, p. 51.

(12) Calculated from: Interprovincial and International Trade in Canada, Catalogue no. 15-546-XIE, 1992-1998, 1984-1996; Canadian International Merchandise Trade, Catalogue no. 65-001-XIB, December 1999.

(13) Industry Canada, pp. N-1-3.

(14) Hufbauer and Schott, p. iii.

(15) The NAFTA, which came into force in 1994, has had a relatively less significant effect on Canada, because it built on the already implemented FTA.

(16) Hart, “The Role of Dispute Settlement in Managing Canada-US Trade and Investment Relations,” Vanishing Borders, p. 99.

(17) Hampson and Molot, “Does the 49th Parallel Matter Any More?” p. 6.

(18) See Canada, Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, The NAFTA at Five Years: A Partnership at Work, April 1999, p. 7. A similar conclusion was reached in the U.S. Administration’s July 1997 report on the NAFTA and its effects, which noted that it was “challenging to isolate NAFTA’s effects on the US economy.”

(19) Hampson and Molot, p. 4.

(20) Hart, “The Role of Dispute Settlement in Managing Canada-US Trade and Investment Relations,” p. 95.

(21) Daniel Schwanen, “Catching Up is Hard to Do: Thinking about the Canada-US Productivity Gap,” Vanishing Borders, pp. 134, 137.

(22) House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, Productivity With a Purpose: Improving the Standard of Living of Canadians, 1999.

(23) Schwanen, p. 137.

(24) McCallum, quoted in “A New Realism,” The Economist, Survey of Canada, Internet edition, 22 July 1999.

(25) Robert Mundell, “Canada’s Dollar: To Fix or Not,” The Nobel Money Duel, dialogue between Robert Mundell and Milton Friedman in the National Post, 12 December 2000, Noel Gaston and Daniel Trefler, “Labour Market Consequences of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement,” Canadian Journal of Economics, February 1997, pp. 18-41, from Todd Hunter, “The Impact of FTA/NAFTA on Canada: What Does the Recent Literature Say?” DFAIT, December 1998, Reference Document No. 6.

(26) Côté, p. 56.

(27) McCallum, “Two Cheers for the FTA.”

(28) Stéphane Roussel, “Canada-American Relations: Time for Cassandra?” The American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer 2000, p. 149.

(29) Deborah Waller Meyers, “Border Management at the Millennium,” The American Review of Canadian Studies, p. 256.

(30) Robert Bothwell, “Friendly, Familiar, Foreign, and Near,” Vanishing Borders, p. 177.

(31) Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Monthly Trade Bulletin, November 2000.

(32) Christopher Sands, “How Canada Policy Is Made in the United States,” Vanishing Borders, p. 70.

(33) Hart, “The Role of Dispute Settlement in Managing Canada-US Trade and Investment Relations,” pp. 112, 113.

(34) Mark MacKinnon, “Canada, U.S. support role for NGO in NAFTA,” The Globe and Mail, 24 November 2000, p. B7.

(35) Gilbert Gagné, “North American Free Trade, Canada, and US Trade Remedies: An Assessment after Ten Years,” The World Economy 23:1, January 2000, pp. 83, 90.

(36) Ibid., p. 86.

(37) Nancy Riche and Robert Baldwin, “Economic Integration and Harmonization with the United States: A Working-Class Perspective,” Vanishing Borders, p. 186.

(38) Alan M. Schwartz, “The Canada-U.S. Environmental Relationship at the Turn of the Century,” The American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer 2000, pp. 207-226.

(39) International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, “US launches free trade talks with Chile,” BRIDGES Weekly Trade News Digest, Vol. 4, No. 46, December 2000.

(40) Legally, citizens of the EU can work throughout the EU. In practice, due to realities such as language barriers, EU labour is not fully mobile.

(41) Hufbauer and Shott, p. 51.

(42) Ibid., p. vi.

(43) Hart, What Next? p. 41.

(44) Julie A. Soloway, “Environmental Regulation as Expropriation: The Case of NAFTA’s Chapter 11,” Canadian Business Law Journal 33:1, February 2000, p. 125, quoting Dani Rodrik, Has Globalization Gone Too Far? Washington: Institute for International Economics, 1997, p. 6.

(45) Thomas J. Courchene, “NAFTA, the Information Revolution, and Canada-U.S. Relations: An Ontario Perspective,” The American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer 2000, pp. 166, 173.

(46) Schawenen, p. 135.

(47) George Hoberg, “Canada and North American Integration,” Canadian Public Policy 26, August 2000, p. s41.

(48) Ibid., p. 190.

(49) Kevin V. Mulcahy, “Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Sovereignty,” The American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer 2000, p. 187.

(50) Riche and Baldwin, p. 188.

(51) Britton, pp. 181, 182.

(52) These are: export, domestic sourcing, domestic content, technology transfer and “exclusive supplier” requirements; and a prohibition on policies reducing imports or tying imports to export performance. Some performance requirements could be imposed if they were tied to government subsidies.

(53) Britton, p. 176, quoting Mel Hurtig, “How Much of Canada Do We Want to Sell?” The Globe and Mail, 5 February 1998, and A.D. MacPherson, “Shifts in Canadian Direct Investment Abroad and Foreign Direct Investment in Canada,” in J. Britton (ed.), Canada and the Global Economy, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.

(54) Weintraub, p. 474.

(55) McCallum, “Two Cheers for the FTA.”

(56) Hufbauer and Schott, p. 59.