PRB 01-4E

OZONE: THE EARTH'S SUNSCREEN

Prepared by:

Joanne Agterberg, Daniel Brassard

Science and Technology Division

2 April 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

2. Impact on Terrestrial Flora

ACTION TO REDUCE THE DESTRUCTIVE AGENTS

APPENDIX: OZONE-DEPLETING SUBSTANCES

OZONE: THE EARTH'S SUNSCREEN

Life on Earth is a delicate balance of many different elements. The conditions necessary for the diversity and abundance of life are fairly restricted and any major change can have unpredictable results. The energy of the sun maintains all forms of life on the planet.

Ultraviolet radiation (UV) is one of the main components of the sun’s energy transmitted to the Earth. This radiation is necessary in moderation; in excess, it can cause serious problems for humans and the biosphere in general. Ozone in the stratosphere moderates the amount of radiation reaching the Earth. The stratosphere is a layer of the atmosphere above the lower layer and denoted by a temperature inversion where ozone acts as the Earth’s sunscreen, filtering out the most harmful wavelengths of UV.

Since the 1970s, we have known that various manufactured products are destroying this life-preserving filter. Findings by the U.S. National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) suggest that upper atmospheric ozone loss in the North will likely continue to increase in the coming years.(1) According to several scientific models and a report issued by Environment Canada, serious depletion episodes could become more frequent over the next 20 years, with the most frequent ozone destruction in the Arctic estimated to occur between 2010 and 2020.(2) This paper will discuss the various aspects of the ozone situation, from technical explanations to the latest efforts to remedy the problem.

Over geological time periods, the atmosphere has changed, becoming the Earth’s protective blanket, enabling life to exist. Life on Earth evolved slowly so that each portion of the ecosystem is adapted to make best use of the available conditions. Over the past century, human activity has altered the atmosphere at an unnaturally rapid rate, thereby reducing the ability of some organisms to adapt.

Although certain modifications to our surroundings are apparent, others are more difficult to observe. Smog, for instance, is very noticeable; however, the altered absorptive and reflective qualities of the atmosphere are more difficult to observe directly.

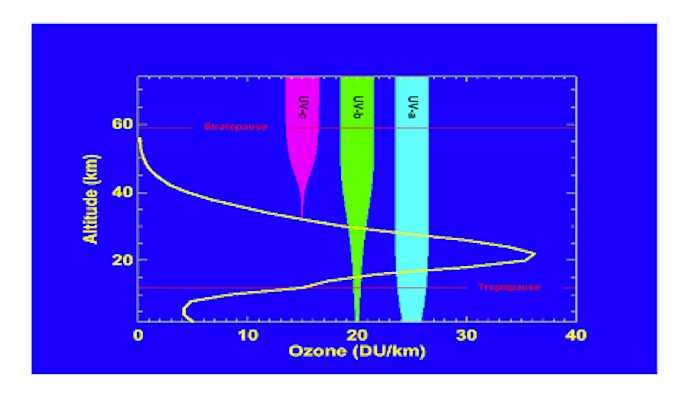

A basic understanding of the processes surrounding this phenomenon is needed to fully appreciate the importance of a reduced quantity of ozone in the upper atmosphere. Ozone (O3) is a pungent-smelling, slightly bluish gas, with one more oxygen atom than molecular oxygen (O2). It can be found at ground level as pollution, where it is harmful to life, and naturally up to an altitude of about 60 km (see Figure 1). Generally, 85% of all ozone is contained in a region of the stratosphere, of varying altitude depending on latitudinal position, known as the ozone layer.(3) On average, the amount of global ozone in the stratosphere is 300 Dobson Units (DU), equivalent to a thickness of pure ozone of only 3 mm, at ground level pressure and 0°C. When stratospheric ozone falls below 200 DU, this is considered the beginnings of an “ozone hole.”

Figure 1

A typical vertical profile of ozone density in the midlatitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (units=Dobson Units/kilometre). The stratosphere lies between the tropopause and stratopause. Superimposed on the figure are plots of UV radiation as a function of altitude for UV-a (320-400 nm), UV-b (280-320 nm), and UV-c (200-280 nm). The width of the bar indicates the amount of energy as a function of altitude. The UV-c energy decreases dramatically as ozone increases because of the strong absorption in the 200-280 nm wavelength band. The UV-b is also strongly absorbed, with a small fraction reaching the surface. The UV-a is only weakly absorbed by ozone, with some scattering of radiation near the surface.(4)

Ozone is produced when high-energy radiation, such as ultraviolet radiation, causes oxygen molecules to split into two oxygen atoms which recombine with other oxygen molecules. The stratospheric concentration of ozone reaches new equilibrium points based on the relative rates of its formation and destruction, which are dependent on various conditions. The greatest ozone losses occur at the altitudes where ozone is most abundant, as can be seen in Figure 2.(5)

Figure 2 (6)

The destruction of stratospheric ozone is complex and involves numerous factors. The process is accelerated by the presence of significant levels of catalysts,(7) specifically chlorine and bromine, members of the extremely reactive “halogen family” of elements. The chlorine and bromine in the stratosphere originate from numerous sources, both man-made and natural. The major source of halogens in the atmosphere is man-made products known as halocarbons,(8) which constituted 82% of chlorine entering the stratosphere in the early 1990s.(9) Natural sources of halogens have a shorter lifespan than halocarbons. Unless injected directly into the stratosphere by major volcanic activity, they are dissolved and washed out by precipitation found in lower regions of the atmosphere where weather is prevalent. Halocarbons do not dissolve in water and therefore all emissions eventually reach the stratosphere via atmospheric mixing, typically over a period of five years.

When halocarbons reach the stratosphere, high-energy ultraviolet radiation and contact with other chemicals break the bonds that hold the atoms together, liberating the halogens to chemically bond in several other ways, as hydrogen chloride or chlorine nitrate, for example.

The stratosphere is known for its absence of clouds, yet ozone depletion occurs most often on polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs), luminescent clouds consisting of super-cooled water, nitric and sulphuric acid. PSCs form at low temperatures and act as active sites(10) on which a very slow reaction in the gas phase can go very quickly heterogeneously, i.e., on solid surfaces. When PSCs occur, the chlorine which is sequestered, by hydrogen ions(11) or nitrogen oxides,(12) is liberated as chlorine gas (Cl2), producing nitric acid.(13) Several other heterogeneous reactions also take place on PSCs, contributing to ozone depletion.

The molecular chlorine is dissociated by solar radiation when polar night has ended. Chlorine atoms react with ozone (O3) to form chlorine monoxide (C1O) and molecular oxygen (O2). Chlorine monoxide then combines with atomic oxygen (O), produced by the process of natural ozone creation, to produce molecular oxygen (O2) and regenerate atomic chlorine (Cl). Typically, one chlorine atom, acting as a catalyst, can destroy up to 100,000 ozone molecules, repeatedly destroying ozone molecules, when conditions are right, for about 100 years.

Polar regions experience the greatest number of PSCs due to a phenomenon known as the polar vortex. This rotating parcel of extremely cold stratospheric air occurs during the long polar night. The vortex prevents atmospheric mixing of additional stratospheric ozone or heat. Rapid ozone loss occurs on these platforms when sunlight returns to photolyse(14) the chlorine molecules. Often PSC particles containing nitrogen will grow in size(15) and settle to a lower level, known as denitrification. Therefore, the chlorine does not become sequestered by nitrogen oxides again but rather a continuation of catalytic ozone destruction occurs.(16)

Because the topography of the Antarctic is generally uniform, the southern polar vortex is stronger than at the Arctic. In localized areas over Antarctica, ozone can drop dramatically by up to 70% in the course of a few weeks.(17)

Environmental consequences of ozone depletion are two-fold. The earth’s radiative energy balance is altered and the amount of harmful ultraviolet solar rays reaching the Earth’s surface increases.

Ozone plays a role in regulating the flow of heat through the atmosphere by absorbing the sun’s radiation. The exact distribution of ozone in the stratosphere thus affects the temperature of the atmosphere and weather patterns. Even small changes in the energy input to the atmosphere from the sun or the energy exchange by radiation between the ground and the atmosphere can influence climate.(18) The temperature distribution in the stratosphere is directly dependent on the distribution of ozone.(19) This is of great consequence because ozone depletion is highly sensitive to temperature.

The sun emits a wide spectrum of energy. Some is in the form of ultraviolet energy, which has a wavelength shorter than violet light. The portion of the ultraviolet light with wavelengths from 280 to 320 nanometres (or 10-9m), known as ultraviolet B (UV-B), is dangerous in excess. UV-C rays are even more energetic, but they are almost fully filtered out by ozone. A decrease in the ozone layer increases UV-B intensity at ground level by approximately twice the percentage decrease, other factors excluded. For example, with an ozone decrease of 30%, UV-B reaching Earth’s surface increases by 60%.(20)

High levels of UV-B cause synthetic materials such as plastic, as well as natural materials including wood, to undergo increased rates of discolouration and weakening. Many classes of materials may be susceptible; research is ongoing.

Ultraviolet light can break the chemical bonds in various substances including DNA, the molecules that encode genetic information. The effects of UV radiation are complex and difficult to interpret, but several consequences of increased levels of UV-B on humans have been confirmed.

Excess exposure to UV-B radiation, especially in childhood, causes higher rates of skin cancer. One reason for this is that UV-B suppresses the skin’s immune responses, so that the body is less likely to reject a growing tumour.(21) A 10% decrease in total stratospheric ozone is expected to cause an additional 300,000 cases of non-melanoma and 4,500 melanoma skin cancers globally each year.(22) Without the Montreal Protocol (discussed below in section entitled “A. International Action”), ozone depletion would have accounted for an additional 20 million cases of skin cancer.(23)

Because ultraviolet light suppresses the immune system, particularly in skin cells, infectious diseases having a stage involving the skin are likely to increase. Also, the effectiveness of vaccines against infectious disease may be limited.(24)

Repeated exposure to excessive UV radiation also sensitizes the eyes to developing cataracts, the main cause of blindness in the world. An estimated 20% of cataracts is due to UV exposure.(25) Other confirmed effects include age-related nearsightedness and deformation of the lens capsule.

To reduce health risks, individuals can do a number of things such as applying a sunscreen with a sun protection factor of at least 15, wearing hats and protective clothing, staying in the shade as much as possible, and wearing high-quality sunglasses treated to absorb UV-B radiation. With proper precautions, the negative health effects of ozone reduction can be minimized.

2. Impact on Terrestrial Flora

The increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation may have a dramatic effect on plant life by affecting hormones and growth. Observed specific effects include:

a reduction in total dry weight, nutrient content, and area available for photosynthesis;

deterioration in the quality of certain types of tomato, legume, cabbage, potato and sugar beet;

diminished flowering/germination rates; and

distribution of nutrients within plants.

While some crops, such as soybean, show decreased production as a result of elevated amounts of UV-B, many other crops are unaffected, or show a high degree of tolerance. Research indicates that the growth and photosynthesis of certain plants (e.g., seedlings of rye, maize and sunflower) can be inhibited even under ambient levels of UV-B.(26)

For many organisms, protective mechanisms may not be sufficient to protect against increased levels of UV radiation. (There are indications that some weeds are more UV-resistant than crops.) Exposure tests have shown that more than 100 species of land plants could be sensitive to increases in UV radiation as a result of stratospheric ozone depletion. International research has revealed that some species of rice suffer from even minor increases in UV-B. Research into the efficient breeding and cultivation of strong species may help to offset some of the damaging effects.

Because the sensitivity of trees and other plant species varies, the diversity and distribution of such species could change, and it is even possible that some species could disappear.(27) Studies show that many species of conifer are negatively affected by increased UV-B radiation.

An increase in the natural level of UV-B is known to cause mutations in microorganisms. However, with the possibility of more rapid mutations, rapid adaptation to UV-B stress may result. Although some research is showing that limited adaptation is possible, most of the effects remain very negative. A decreased rate of the fixing of atmospheric nitrogen by fungi would require significant global substitution by artificial fertilizer.(28) Nitrogen compounds, largely produced by microorganisms in the soil, seem to play a major role in the natural control of ozone levels.(29)

All areas of the biosphere appear to be affected by increased UV-B to some extent, some more so than others. Phytoplankton (phyto = plant) is highly sensitive to UV radiation; it lacks the protective layers of higher forms of life and drifts along at the water’s surface where exposure to UV-B can occur. As well as being the basis of the aquatic food web, phytoplankton is a major oxygen producer and a carbon sink, known to assimilate large amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Marine phytoplankton produces at least as much biomass as all terrestrial ecosystems combined. Changes to phytoplankton production could exacerbate the greenhouse effect.

Scientists at the University of Plymouth have found that the reproductive cells of algae are several times more sensitive to ultraviolet radiation than are mature cells. Laboratory research revealed that asexual spores of the selected species were six times more sensitive to UV-B than were mature plankton. Free-swimming gametes, the sexual means of reproduction, were even more susceptible. Ecological impact could be greatest at particular times in the spring, during so-called “blooms” when plankton reproduction is most intense.(30) Assessment of these effects on phytoplankton is difficult because of the lack of data describing UV-B and biological levels during the period before the depletion of the ozone layer.

Zooplankton (zoo = animal) – small organisms, such as fish and crustacean larvae – are at risk as well as anchovies because they spend critical periods near the surface of the water where UV-B can penetrate. A reduction of these organisms found near the base of the food chain could result in a reduction of the fish population. This may have an adverse impact on the global food supply. Fish account for 18% of the animal protein in the world and 40% of the protein consumed in Asia.(31) Freshwater marine ecosystems are also at risk from the intensification of UV-B exposure.(32)

There is widespread agreement that ozone-related increases in UV-B have the potential to cause wide-ranging direct and indirect effects on aquatic ecosystems, especially at the poles where life forms are less acclimatized to intense sunlight. Studies generally show that the increased UV radiation under the Antarctic ozone hole reduces plankton production by between 6% and 12% during exposure. Damage at the molecular, cellular, population and community levels has been demonstrated.

Atmospheric changes resulting from the increased UV-B radiation are of special concern. Diminished air quality in the troposphere, the lower level of the atmosphere, has been noted. Chemical reactivity in the troposphere increases in response to increased UV-B, resulting in higher levels of air pollution. UV-B stimulates the formation of molecules that react rapidly with other chemicals to form new substances. For example, hydroxyl radicals are generated, which contribute to the creation of ground level ozone, aerosols and other harmful pollutants. In urban areas, a 10% reduction of the ozone layer is likely to result in a 10-25% increase in tropospheric ozone. Irradiated smog contributes to oxidized organic(33) chemicals, such as formaldehydes. These molecules tend to form reactive hydrogen radicals, which contribute to the formation of hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide is the principal chemical that oxidizes sulfur dioxide to form sulfuric acid in cloud water, making it an important part of acid rain formation.(34)

Increasingly severe ozone depletion now occurs each spring over Antarctica (see Figure 3), and the year-round levels are lower than normal. The year 2000 ozone hole was the largest ever over Antarctica, forming two weeks earlier than before and extending past the polar vortex.(35)

Figure 3 (36)

|

Arctic ozone depletion has not occurred as dramatically as over the Antarctic. The Arctic region’s polar vortex usually dissipates in late winter before sunlight returns. However, occurrences of significant ozone depletion are becoming more frequent in the Arctic. Many international projects involving satellites, high altitude aircraft, balloons and ground stations are helping to improve understanding of processes that govern the generation, depletion and distribution of ozone. A variety of techniques are used to detect and measure the various factors involved. NASA’s Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) was launched in September 1991. This satellite was configured to measure levels of ozone-depleting chemicals as well as ozone levels at various altitudes. The U.S. TOMS (Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer) satellite is used to deduce the ozone levels from the back-scattered sunlight in the UV range.

The Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME), launched in April 1995 on the European ERS-2 satellite, marked the beginning of a long-term ozone monitoring effort. Scientists receive high-quality data on the global distribution of ozone and several other climate-influencing trace gases in the Earth’s atmosphere. GODIVA is the Global Ozone Data Interpretation, Validation and Application component of GOME, which also contributes to other experiments such as the Third European Stratospheric Experiment on Ozone 2000 (THESEO 2000) and the SAGE III Ozone Loss and Validation Experiment (SOLVE) which have been conducted jointly. More than 350 researchers have participated from the U.S., Europe, Russia, Japan and Canada. Project results support the theory that recovery of the ozone layer may be delayed due to a strengthening of the polar vortex and a cooling of the stratosphere.

Environment Canada is involved in a variety of experiments dealing with ozone chemistry, such as the Canadian Middle Atmosphere Initiative, with the purpose of modeling, assimilating data, and monitoring this region of the atmosphere.(37) A Canadian satellite (SCISAT-1) of the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE) is expected to be launched in 2002 to study global ozone depletion.(38)

Analysis of satellite data reveals that the loss of ozone in the Northern Hemisphere is now proceeding faster than previously thought. Although no Arctic ozone losses comparable with those in the Antarctic have occurred, ozone losses have increased greatly during the 1990s in the Arctic. Isolated ozone losses approaching 45% give cause for concern due to the higher number of human populations than at the South Pole.(39)

At both poles, ozone loss is expected to grow larger during the coming decades before recovering. It has been recently discovered that greenhouse gases are causing more dramatic upper-atmospheric cooling.(40) Computer models predict that temperature and wind changes induced by greenhouse gas emissions may allow a stronger and longer-lasting atmospheric vortex to form above the Arctic.

When concern about the ozone layer first surfaced in the 1970s, attention initially focused on advanced aircraft as the root of the problem, then shifted to the ordinary aerosol spray can. The group of industrial chemicals known as CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) were used as propellants at that time. Thousands of tonnes were being released directly into the lower atmosphere where they began their gradual drift upward to destroy the stratospheric ozone. Since then, the list of materials known to destroy the stratospheric ozone has greatly expanded.

The impact of aircraft on stratospheric ozone depletion is still being researched.(41) Studies have shown that improved efficiency and management strategies are required to reduce aviation’s impact on ozone depletion.(42) In-flight measurements of emissions were taken of supersonic exhaust, greatly contributing to the reliability of studies regarding the effect of this form of transportation on stratospheric ozone.(43) Emissions of nitrogen compounds (NO and NO2) from supersonic aircraft is of concern, due to the inevitability of increasing fleet size and the high altitudes of flight.

CFCs, and the other ozone-destroying agents, are ubiquitous in almost every society. They are used in a wide range of products that are frequently not recognized as containing ozone-destroying materials. Because of the range of materials involved, the term “ozone-depleting potential” (ODP) was adopted to indicate the potential of a substance to destroy ozone, on a mass-per-kilogram basis, compared to an ODP value of one given to Trichlorofluoromethane, known as CFC-11 in the conventional system of classification. The ODP is based upon various factors such as the substance’s atmospheric lifetime, molecular weight, its ability to be photolytically disassociated, and other factors determined to provide an accurate estimate of the relative ozone-depletion potential.

The table in the Appendix lists many ozone-destroying agents with associated ODP, as well as some replacements for CFCs. The hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), the current replacement for CFCs, have a low ODP, while the hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) have a zero ODP and so are not included. Ongoing research causes some ODP values to be updated over time. Lifespans are still being measured. UNEP rates a country’s progress in meeting goals by measuring production of groups of ozone-depleting substances in ODP tonnes (metric tonnes times ODP).

Quantitatively, CFCs have been the main ozone-destroying agents. Because of their stable, non-toxic, non-flammable and non-corrosive characteristics, they have been used in refrigeration, aerosols, solvents, and the production of foams. Alternative technologies have been developed for many of these applications, and the current challenge is to ensure that the vast existing amounts of CFCs used in refrigeration and air conditioning are reclaimed rather than permitted to escape into the atmosphere.

The other major group of ozone-destroying agents are the halons, which are of similar composition to CFCs but contain bromine. Halons are used as fire-fighting chemicals for numerous reasons, including their low toxicity, unobstructed visibility during discharge, low corrosive or abrasive residue, and high effectiveness per pound. Although the production of halons in developed countries has been largely phased out since 1994, the stratospheric concentration of these potent ozone destroyers is still rising, due to their long atmospheric lifetimes and the time required for atmospheric mixing. In developing countries, there are no restrictions on halons until January 2002. Halons have an extremely high ozone-depleting potential (three to ten times higher than CFCs), and their intended use results in release directly to the atmosphere. The remaining agents – such as carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform, and methyl bromide – have been used in several ways, for example, as feedstocks to produce CFCs, in pesticides and in dry cleaning agents.

In 1997, the overall halocarbon burden in the stratosphere, or effective equivalent chlorine (EECL), began to decrease, largely due to the phasing out of trichloroethane, a cleaning solvent. Due to its relatively short lifespan of 4.8 years, it is now largely absent from the stratosphere. Without this influence, the EECL would still be rising; however, the EECL may not decrease significantly more unless emissions of potent, longer-lasting ozone-depleting substances (ODS) decline further by 2010. The chemical currently contributing the most to EECL in the atmosphere is halon-1211. Amounts have remained relatively constant in the stratosphere despite limitations on its production in developed countries.(44)

The need to reduce the use of ozone-destroying agents has stimulated many technological innovations and the use of alternative materials for each application. Noteworthy innovations include new propellants, solvents, foaming agents, fire suppressants, and pest management techniques.(45) The urgent need for change has also made progress in recovery and recycling technology indispensable. The largest and most difficult changes have taken place in refrigeration and air conditioning. Most of the research has been aimed at finding alternatives to CFCs as a refrigerant.

CFCs have been largely phased out in developed countries. Many replacements have been based on HCFCs and to some extent on HFCs. The first use of HFC-134 in automobile air conditioners was in 1991, but its use is quickly expanding. One of the problems associated with the use of HCFCs and HFCs is that they are less energy efficient than CFCs. DuPont, the world’s largest producer of CFCs, halted CFC production in 1993, five years earlier than originally planned, and now produces HCFCs and HFCs. HCFCs are very strong greenhouse gases, designated by amendments to the Montreal Protocol to be phased out by 2030 in developed countries. Some HFCs also have a large global warming potential and long lifetimes.

An exciting advance towards resolving the refrigerant problem is the development of the thermoacoustic refrigerator, which has no moving parts and uses environmentally benign gases. Although the principle on which it works is simple, the actual design is complex. A loudspeaker at the end of a tube produces a loud note that resonates inside a gas-filled tube. This generates a standing wave,(46) which effectively transmits the heat towards the antinode.(47),(48) Because this vibration is accurately controlled, thermoacoustic refrigerators will be quieter than conventional refrigerators. A recent demonstration at the Los Alamos National Laboratory showed how the design could be simplified by eliminating the cold heat exchanger and cooling the thermoacoustic working gas instead.(49)

Another exciting innovation is the magnetic refrigerator, developed by Astronautics Corporation of America under a contract with the U.S. Department of Energy. It has comparable energy efficiency to conventional household units. The cost of the gadolinium magnet is the major obstacle to its widespread use, although in the near future it will likely be marketed to large-scale commercial enterprises.(50)

Other solutions include designs with less coolant but larger surface area coverage of the coolant. An inexpensive yet useful alternative for desert living recently earned Mohammed Bah Abba of Nigeria a Rolex Prize for enterprise. The system, based on the cooling properties of evaporation, uses damp sand between clay pots.(51) Ionizing radiation is also an alternative to refrigeration for preserving food supplies.(52)

Ammonia is widely used as a refrigerant in industry, for cold storage warehouses and petrochemical facilities, as examples. The shortcomings of this refrigerant are its corrosive and flammable nature at certain concentrations in air. Accidental releases, which are exacerbated by the pressurized nature of this refrigeration system, have caused injury and death from inhalation of the fumes and have contaminated water.(53) In terms of the ozone layer, ammonia would form other stable compounds before reaching the stratosphere.

Solutions to CFC usage in the production of foams, for uses ranging from insulation to foam cups, have included lessening the amount of propellant required and replacing the CFCs with less-damaging HCFCs. The Lily Cup Inc., of Toronto, has developed an innovative technique after many years of research, which uses oxygen and recycled carbon dioxide as a foaming agent.(54)

Changes have been made even in the health care sector. For example, hospitals have reduced the use of CFCs as sterilants. Canada is phasing out CFC propellants in metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) by 2005. The first CFC-free MDI was approved for use in August 1997. In this product, the CFC propellant has been replaced by hydrofluoroalkane (HFA), which does not cause ozone depletion. The safety of HFA for medicinal use has been demonstrated through extensive testing. The CFC-free MDI has now been approved for use in more than 35 countries.(55)

The electronics industry was one of the principal users of CFC-based solvents. For most applications, new solvents that do not use CFCs have been developed. In 1991, Northern Telecom developed and implemented an alternative technology for soldering electronic circuit boards which did not involve needing to use solvents first.(56) The company co-founded the Industry Co-operative for Ozone Layer (now the International Co-operative for Environmental Leadership), which shares new technology. This earned Northern Telecom the Financial Post 1993 Appropriate Technology Award.(57) Many large electronic manufacturers have now eliminated the use of CFCs.

Heat treatment, the use of diatomaceous earth, or live biological control are alternatives to the use of methyl bromide as a produce and crop fumigant. Knowzone Solutions Inc., of Canada, recently acquired the rights to the BromosorbŪ Technology for the capture of methyl bromide after fumigation.

Securiplex Inc. of Canada has developed several alternatives to halons in fire protection, which rapidly extinguish fires without equipment damage.

ACTION TO REDUCE THE DESTRUCTIVE AGENTS

The international community has taken up the challenge of halting the destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer. This is one of the main reasons for the rapid technological development of alternatives to CFCs. Canada, a very active participant in international discussions, took early action. In March 1980, this country prohibited the use of CFCs in most common consumer aerosols, such as hairsprays, deodorants and antiperspirants.

In 1985, the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer called for voluntary measures to reduce emissions of ozone-depleting substances.(58) Canada was the first nation to ratify the Vienna Convention in June 1986. More comprehensive initiatives have been agreed to since this first major international agreement.

In an unprecedented demonstration of global cooperation, the world’s nations committed themselves to stringent action to protect the ozone layer. In September 1987 they adopted the Montreal Protocol, a schedule to reduce and eventually eliminate the production of CFCs and halons. The Montreal Protocol works through a system of trade barriers controlling the supply of ODS, while permitting transfer of essential use exemptions between parties. It came into effect 1 January 1989. The results of the Montreal Protocol have led to a peaking of chlorinated substances in the stratosphere.

Amendments to the Protocol have:

advanced the schedule for phase-out of chemical compounds destructive to ozone in the stratosphere;

added additional ODS to the list; and

altered requirements for essential use exemptions.

Even as the Montreal Protocol was being signed, it was recognized that it needed stronger controls, which were effected at the London conference in 1990. The Protocol’s list of controlled substances was expanded by ten, including methyl chloroform and carbon tetrachloride. Phase-out dates were set for 2000 and 2010 for developed and developing countries, respectively. Many parties at this conference committed themselves to the elimination of CFCs by 1997, three years ahead of the international target. This amendment included the provision of a fund to assist developing nations operating under Article 5 of the Protocol. The Multilateral Fund has subsequently been assisting developing nations to switch to more ozone-friendly substances and technology by providing financial assistance, training and technological information. Implementing Agencies of the Multilateral Ozone Fund include:

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP);

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP);

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO); and

World Bank.

The 1992 Copenhagen Amendment tightened the schedule so that developed countries were to phase out CFCs, carbon tetrachloride and methyl chloroform by 1996 and halons by 1994. Methyl bromide and hydrobromofluorocarbons (HBFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) were also added to the list of substances to be phased out by 1996 and 2030, respectively. This amendment also strengthened trade controls and non-compliance procedures.

The 1995 Vienna Adjustments froze the production and consumption of methyl bromide at 1995-1998 levels and planned to freeze consumption levels of HCFCs in 2016.

The Montreal Amendment, developed in 1997, moved the phase-out date of methyl bromide to 2005 and 2015 for developed and developing countries, respectively. A new licensing system involving regular exchange of information between parties was developed to arrest illegal trade in ODS.

Initiatives of the December 1999 Beijing Amendment, which Canada was one of the first countries to accept, has yet to be ratified by the 20 countries required to bring it into force. It includes new controls on the production of HCFCs, freezing production at 1989 levels in 2004 towards a phase-out in 2030 in industrialized countries, and a freeze at 2015 levels in developing countries in 2016.(59) The new amendment also bans trade in HCFCs in 2004 with countries which have not yet ratified the 1992 Copenhagen amendment. Phase-out of a recently developed ODS, bromochloromethane, is to be carried out in all countries by 2002. At the same time, the Executive Committee of the Multilateral Ozone Fund decided to increase aid to India and China in cutting production over the next ten years. These countries have had difficulty meeting reduction targets.(60)

Imports of newly produced CFCs and halons by developed countries have largely been banned, as have imports and exports of other potent ODS. Existing ozone-depleting substances are re-used and recycled where possible. Developing countries have been extended a period of grace under Article 5 of the Protocol so long as their use of ODS does not grow significantly. These parties have kept their production of CFCs at the 1995-1997 baseline levels and are beginning the process of phasing out the use of these substances to 50% by the year 2005.

Eastern European and large Asian nations – such as Russia, China and India – are having difficulty incorporating advanced refrigeration technologies. With collaboration, the much-needed changes are being made just as these massive populations begin to fully share in this desirable technology. Currently, China is the world’s largest producer of CFCs and halons. The Global Environmental Facility, through UNDP, has been assisting the phase-out of Russian CFC production facilities and the modernization of appliance manufacturing in China(61) and India; both of these countries are beginning to produce refrigerators which use hydrofluorocarbon and isobutane.(62)

In 1997, the total costs of the measures taken to protect the ozone layer were calculated to be US $235 billion. However, the avoided adverse effects on fisheries, agriculture and materials alone are estimated to be twice that expenditure.(63)

Canada has revised the Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODS) Regulations, 1998, under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, as of January 2001, to: address the amendments to the Montreal Protocol; improve controls on ODS; and address administrative issues.

Federal regulations prohibit production and importation of CFC and halons in most cases, and set out strict controls on exports. Current federal regulations prohibit import and export of recovered halons except by permit.

Restrictions on the refilling of equipment encourage conversion to alternatives. The transition is made easier due to the imposition of decreased supply so that the cost of CFCs is increasing steadily while the cost of replacements is decreasing. Canadian ODS reduction is apparent in the following figure.

Figure 4 (64)

CANADIAN ODS CONSUMPTION (kilotonnes)

In 1996, manufacturers started using alternative refrigerants for new equipment. However, a large number of CFC-containing units remained available on the market until recently. These appliances have a long service life of approximately 13-15 years. The stock of CFCs should be available for servicing household appliances until 2020.

Production of carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform, and methyl bromide has been phased out in industrialized nations and there is not a serious surplus to manage in Canada.

At this time, Canada has one permanent approved incineration facility for disposal of ODS, located at Swan Hills, Alberta. Because the facility has limited capacity, Canada may allow the export of ODS for destruction at a suitable facility abroad. Currently, other facilities capable of destroying ODS are operating in Australia, Sweden, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, Russia and the United States.

To permit Canadians to take suitable precautions against increased UV-B levels, Environment Canada announced an advisory service shortly after NASA had confirmed the strong possibility of a substantial reduction of the ozone layer over a large area of Canada. The service began 13 March 1992, much sooner than originally planned, and provides daily information on guarding against exposure to the sun in view of changing UV-B levels, making Canada the first country to issue nation-wide daily forecasts of solar UV radiation. The UV Index has been emulated around the world, allowing the public to limit their exposure when the harmful rays are most intense.(65)

A cross-country network of monitoring stations has kept continuous watch on Canada’s ozone layer for more than three decades. The existence of these early records, before any major human influence on the upper atmosphere, is vital to understanding the changes that have occurred. The World Ozone and Ultraviolet Radiation Data Centre (WOUDC) is one of six recognized World Data Centres which are part of the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) programme which in turn is part of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The WOUDC, operated by the Experimental Studies Division of the Meteorological Service of Canada,(66) is located in Toronto.

International agreements have been translated into national objectives. In Canada, the federal government has been working very cooperatively with the provinces to implement the necessary changes. Industry has also become increasingly involved. The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) directed in April 1989 that the Federal-Provincial Action Committee (FPAC) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act coordinate the development of controls across all jurisdictions. The CCME has taken the lead in organizing multi-jurisdictional participation in the reduction, recovery and recycling of CFCs. On 21 August 1990, the CCME established a working group to develop a National Action Plan for reduction, recovery and recycling.

The CCME accepted and published the National Action Plan in 1992. The rapid development of such a major plan demonstrates the level of cooperation between the various governments on this important environmental issue. This plan identified six major tasks, which have been completed or are ongoing:

1. To mandate, under provincial regulations, the recovery, recycling and reclamation of CFCs and HCFCs from all refrigeration and air conditioning uses. This includes banning the deliberate release of CFCs and HCFCs into the atmosphere.

2. To develop, in conjunction with industry trade associations, training programs in recovery and recycling for the service sector. The training would include the Federal Code of Practice for Emission Reduction of CFCs, as well as hands-on equipment training.

3. To characterize the existing bank of CFCs in Canada, necessary to measure the effectiveness of recovery/recycling activities and to plan for ultimate destruction scenarios.

4. To develop, with the involvement of industry and standards associations, appropriate standards for the quality of recycled refrigerant and for the performance of recovery equipment.

5. To ensure that the general public is informed of the problem and the solutions. The public’s reaction and participation is an integral part of resolving the problem.

6. To revise government purchasing/procurement standards, including service contracts, to ensure recovery and recycling of CFCs, HCFCs and halons.

The most recent National Action Plan for the Environmental Control of Ozone-Depleting Substances and their Halocarbon Alternatives (NAP), published in 1998 by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, aims to continue to reduce emissions of ozone-depleting substances.

In 1998, NAP stated the following objectives:

To improve the environmental management of all ODS and halocarbon alternatives and to reduce their emissions during the installation, operation, maintenance, repair, disposal, and decommissioning of systems and equipment.

To provide consistency for industry and to minimize the impact on other environmental issues.

To meet these new needs by revising the original tasks, including:

- the continuation of original tasks as needed;

- original tasks that have been expanded to include halocarbon alternatives;

- new tasks to reflect the revised “Environmental Code of Practice for Elimination of Fluorocarbon Emissions from Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Systems” and to enhance the recovery of refrigerants;

- new tasks reflecting the “Code of Practice for halons”;

- new tasks focused on other industry sectors to reduce fluorocarbon emission; and

- new tasks to provide basic information necessary for controlling future actions.

All provincial governments and one territorial government have regulations controlling the release of ODS and mandating recovery and recycling.(67)

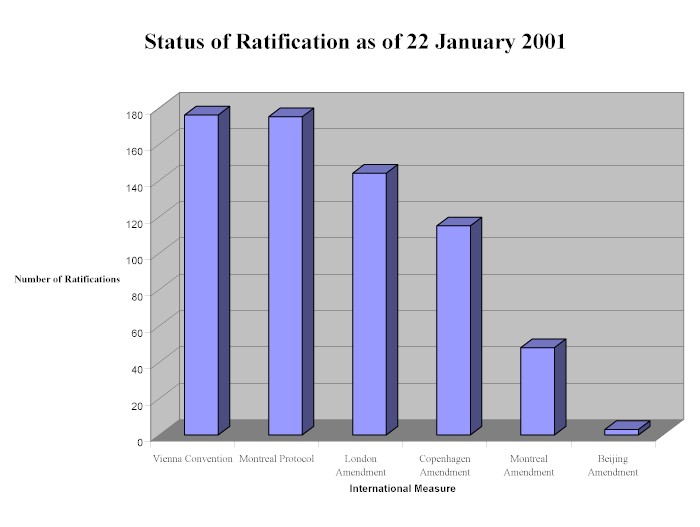

At the most recent meeting of the parties, in Beijing, the Executive Secretary of the Ozone Secretariat, K. Madhava Sarma, noted that consumption and production of ODS has fallen by nearly 90% but that there are hurdles to overcome. These were listed as growing emissions due to:

exemptions;

increased global warming which could delay the ozone layer’s recovery;

new ozone-depleting substances coming onto the market; and

slow ratification of the Protocol’s amendments, illustrated in Figure 5.(68)

Figure 5

As previously mentioned, HCFCs – the current replacements for CFCs – are scheduled to be phased out in the next few decades due to their high greenhouse gas potential, so that replacements for these, too, will be needed.

Vast inventories of equipment and materials containing CFCs still exist. The phase-out continues for developed nations, which have been using CFCs since they were invented more than 50 years ago. If ODS are not successfully phased out of the growing economies of Asia, in particular, the Protocol will not succeed.

Much of the foam and insulation containing CFCs are in refuse piles with liberation of these ODS remaining uncertain. In addition, the world has a billion refrigeration and air conditioning units, many of which are poorly maintained and leaking CFCs, and which, when they are no longer serviceable, are simply thrown into landfill sites. These vast quantities of CFCs may still find their way into the atmosphere.

As a result of the decline in the production and use of CFCs in developed countries and the continuation of CFC production in developing countries until 2010, lucrative international smuggling of CFCs exists.(69) The extent of the smuggling is an estimated 10% of the legal trade.(70) Parties of the Montreal Protocol have been urged at meetings to install licensing programs and to subject smugglers to heavy penalties. The United States currently has the largest black market of ODS.(71) To address the issue of smuggling, surveyed countries suggested the following actions:

drafting legislation;

coordinating agencies;

implementing a system of licensing; and

training prosecutors, investigative agents and customs officials.(72)

It has recently been understood that although “greenhouse gases” are warming the atmosphere near the Earth’s surface, they are also cooling the stratosphere by altering the radiative balance and consequently strengthening the Arctic polar vortex.(73) It must be recognized that global warming is inter-connected with ozone depletion in the stratosphere. In February of 1999, Hartmut Grassl, the director of the UN’s World Climate Research Programme, made the upper atmosphere his new number one priority in the wake of concern that not enough is known about changes in the upper atmosphere above inhabited polar regions of the North.(74)

Life on Earth remains a delicate balance of many different elements. Use of ozone-depleting substances has jeopardized what acts as the Earth’s sunscreen. The harmful effects of increased UV-B have been worsening. Now that research is confirming a connection between climate change and depletion of the ozone layer, predictions for recovery have been extended.(75)

The international community has cooperated as never before to remedy this situation. The reduction, recycling and replacement of ozone-destroying substances is progressing. Thus far, industrialized countries have reduced production and consumption of ODS by 85%.(76) New technologies are being developed so that ozone-depleting agents can be eliminated. Although the concentration of chlorine is declining in the stratosphere and the rate of increase of halons is slowing, several models now show the peak of ozone depletion occurring around the year 2020, rather than the previous estimate of the year 2000.(77) Had there not been international effort to limit the amount of ozone-depleting chemicals in the atmosphere, the situation would be much worse, and would have continued for many more decades.

If international commitments are kept, the ozone layer is expected to recover to pre-1980 levels during the latter half of this century.(78) With the intricacies and inter-relationships of ozone chemistry and mechanics of the upper atmosphere unfolding, the global community’s full compliance with the Montreal Protocol and with efforts to control greenhouse gases is proving necessary in regaining the natural balance between ozone production and destruction in the upper atmosphere.

Ozone-Depleting Substances

| Chemical Name | Lifetime, in years |

ODP |

| CFC-11 (CCl3F) Trichlorofluoromethane |

45 | 1.0 |

| CFC-12 (CCl2F2) Dichlorodifluoromethane |

100 | 1.0 |

| CFC-113 (C2F3Cl3) 1,1,2-Trichlorotrifluoroethane |

85 | 0.8 |

| CFC-114 (C2F4Cl2)

Dichlorotetrafluoroethane |

300 | 1.0 |

| CFC-115 (C2F5Cl) Monochloropentafluoroethane |

1700 | 0.6 |

| Halon 1211 (CF2ClBr) Bromochlorodifluoromethane |

11 | 3.0 |

| Halon 1301 (CF3Br) Bromotrifluoromethane |

65 | 10.0 |

| Halon 2402 (C2F4Br2) Dibromotetrafluoroethane |

6.0 | |

| CFC-13 (CF3Cl) Chlorotrifluoromethane |

640 | 1.0 |

| CFC-111 (C2FCl5) Pentachlorofluoroethane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-112 (C2F2Cl4) Tetrachlorodifluoroethane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-111 (C3FCl7) Heptachlorofluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-112 (C3F2Cl6) Hexachlorodifluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-113 (C3F3Cl5) Pentachlorotrifluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-114 (C3F4Cl4) Tetrachlorotetrafluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-115 (C3F5Cl3) Trichloropentafluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-116 (C3F6Cl2) Dichlorohexafluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CFC-117 (C3F7Cl) Chloroheptafluoropropane |

1.0 | |

| CC14 Carbon tetrachloride | 35 | 1.1 |

| Methyl Chloroform

(C2H3Cl3) 1,1,1-trichloroethane |

4.8 | 0.1 |

| Methyl Bromide (CH3Br) | 0.7 | |

| CHFBr2 | 1.0 | |

| HBFC-12B1 (CHF2Br) | 0.74 | |

| CH2FBr | 0.73 | |

| C2HFBr4 | 0.3 – 0.8 | |

| C2HF2Br3 | 0.5 – 1.8 | |

| C2HF3Br2 | 0.4 – 1.6 | |

| C2HF4Br | 0.7 – 1.2 | |

| C2H2FBr3 | 0.1 – 1.1 | |

| C2H2F2Br2 | 0.2 – 1.5 | |

| C2H2F3Br | 0.7 – 1.6 | |

| C2H3FBr2 | 0.1 – 1.7 | |

| C2H3F2Br | 0.2 – 1.1 | |

| C2H4 Br | 0.07 – 0.1 | |

| C3HFBr6 | 0.3 – 1.5 | |

| C3HF2Br5 | 0.2 – 1.9 | |

| C3HF3Br4 | 0.3 – 1.8 | |

| C3HF4Br3 | 0.5 – 2.2 | |

| C3HF5Br2 | 0.9 – 2.0 | |

| C3HF6Br | 0.7 – 3.3 | |

| C3H2FBr5 | 0.1 – 1.9 | |

| C3H2F2Br4 | 0.2 – 2.1 | |

| C3H2F3Br3 | 0.2 – 5.6 | |

| C3H2F4Br2 | 0.3 – 7.5 | |

| C3H2F5Br | 0.9 – 1.4 | |

| C3H3FBr4 | 0.08 – 1.9 | |

| C3H3F2Br3 | 0.1 – 3.1 | |

| C3H3F3Br2 | 0.1 – 2.5 | |

| C3H3F4Br | 0.3 – 4.4 | |

| C3H4FBr3 | 0.03 – 0.3 | |

| C3H4F2Br2 | 0.1 – 1.0 | |

| C3H4F3Br | 0.07 – 0.8 | |

| C3H5FBr2 | 0.04 – 0.4 | |

| C3H5F2Br | 0.07 – 0.8 | |

| C3H6FBr | 0.02 – 0.7 | |

| HCFC-12 (CHF2Cl) Monochlorodifluoromethane |

11.8 | 0.055 |

| HCFC-123 (C2HF3Cl2) Dichlorotrifluoroethane |

1.4 | 0.02 |

| HCFC-124 (C2HF4Cl) Monochlorotetrafluoroethane |

6.1 | 0.022 |

| HCFC-141b (C2H3FCl2) Dichlorofluoroethane |

9.2 | 0.11 |

| HCFC-142b (C2H3F2Cl) Monochlorodifluoroethane |

18.5 | 0.065 |

| HCFC-225ca (C3HF5Cl2) Dichloropentafluoropropane |

2.1 | 0.025 |

| HCFC-225cb (C3HF5Cl2) Dichloropentafluoropropane |

6.2 | 0.033 |

Source: United

States Environmental Protection Agency, Global Programs Division, October 2000![]()

Original Sources: Figures in the Lifetime column are from Table 10-8 of the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, 1998, a report of the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project. Figures in the ODP column are from Table 11-1 of the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion. Blanks in the data indicate that the information was not shown in the original source.

(1) National Aeronautics & Space Administration, Ames Research Center, NASA News, April 2000.

(2) Environment Canada, Arctic Ozone: The Sensitivity of the Ozone Layer to Chemical Depletion and Climate Change, December 1998.

(3) Environment Canada, Atmospheric Climate Science Directorate, “Stratospheric Ozone,” January 2001.

(4) Paul A. Newman, SAGE III Ozone Loss and Validation Experiment, SOLVE: A NASA DC-8, ER-2 and High Altitude Balloon Mission, National Aeronautics & Space Administration/Goddard Space Flight Center, March 1999.

(5) Paul J. Crutzen and Veerabhadran Ramanathan, “Pathways of Discovery – The Ascent of Atmospheric Sciences,” Science, Vol. 290, 13 October 2000.

(6) United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), The Ozone Secretariat, Frequently Asked Questions About Ozone to the Scientific Assessment Panel, 2000.

(7) Catalysts are characterized by the same quantity being present at the beginning and end of a reaction.

(8) The general term for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), and other substances of similar composition containing bromine.

(9) UNEP, Frequently Asked Questions About Ozone to the Scientific Assessment Panel, 2000.

(10) Thomas G. Chasteen, Ozone’s Problem with Polar Stratospheric Clouds, Dept. of Chemistry, Sam Houston State University, Spring 1997.

(11) Charged particles.

(12) Ibid.

(13) Newman, SAGE III Ozone Loss and Validation Experiment, 1999.

(14) Break apart due to ultraviolet radiation.

(15) Richard A. Kerr, “Stratospheric ‘Rocks’ May Bode Ill for Ozone,” Science, Vol. 291, No. 5506, February 2001.

(16) Christiane Voigt et al., “Nitric Acid Trihydrate (NAT) in Polar Stratospheric Clouds,” Science,Vol. 290, No. 5497, October 2000.

(17) Ibid.

(18) Environment Canada, Stratospheric Ozone, January 2001.

(19) Environment Canada, Arctic Ozone, 1998.

(20) UNEP, State of the Environment Norway, GRID-Adrendal, Original source: UNEP/ (GEMS) library series no 7: The Impact of Ozone Layer Depletion, May 1997.

(21) Ibid.

(22) World Health Organization, “The Global UV Project Summary,” Intersun, October 1998.

(23) “11th MOP to the Montreal Protocol and 5th COP to the Vienna Convention,” Linkages, December 1999.

(24) UNEP, State of the Environment Norway, 1997.

(25) World Health Organization, “The Global UV Project Summary,” 1998.

(26) Environmental Effects of Ozone Depletion: 1991 Update (1991), p. iii.

(27) Synthesis of the Reports of the Ozone Scientific Assessment Panel, Environmental Effects Assessment Panel, Technology and Economic Assessment Panel, Prepared by the Assessment Chairs for the Parties to the Montreal Protocol, November 1991, p. 6.

(28) Ibid., p. iv.

(29) Crutzen and Ramanathan, “Pathways of Discovery,” 2000.

(30) Fred Pearce, “Algal Gloom,” New Scientist, August 1998.

(31) Stephen O. Anderson, “Halons and the Stratospheric Ozone Issue,” Fire Journal, Vol. 8, No. 3, May-June 1987.

(32) Reinhard Pienitz and Warwick F. Vincent, “Effect of climate change relative to ozone depletion on UV exposure in sub arctic lakes,” Nature, pp. 404, 484-487, March 2000.

(33) Containing carbon.

(34) UNEP, State of the Environment Norway, 1997.

(35) The 2000 ozone hole, British Antarctic Survey, December 2000.

(36) UNEP, Frequently Asked Questions About Ozone to the Scientific Assessment Panel, 2000.

(37) Environment Canada, The Canadian Middle Atmosphere Initiative, April 2000.

(38) Canadian Space Agency, SCISAT-1: Canada’s next scientific satellite, Apogee – Space Science, October 1999.

(39) Environment Canada, Arctic Ozone, 1998.

(40) Fred Pearce, “Chill in the air,” New Scientist, May 1999.

(41) Joyce E. Penner et al.,“Aviation and the Global Atmosphere Summary for Policy Makers,” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, United Nations Environment Programme/World Meteorological Organization, April 1999.

(42) “Summary of the Eleventh Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol and the Fifth Conference of the Parties to the Vienna Convention,” Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 6, December 1999.

(43) “Supersonic Aircraft Exhaust Measurements to Help Ozone Aircraft Studies,” NASA HQ Public Affairs Office, October 1995.

(44) S.A. Montzka, J.H. Butler, J.W. Elkins, T.M. Tompson, A.D. Clarke and L.T. Lock, “Present and future trends in the atmospheric burden of ozone-depleting halogens,” Nature, Vol. 398, April 1999.

(45) Environment Canada, “Success Stories – Finding Alternatives,” The Green Lane, 1997.

(46) A stationary wave formed of several identical waves overlapping.

(47) The region of maximum amplitude between two adjacent nodes in a standing wave.

(48) “Cooling with Sound: An Effort to Save Ozone Shield,” New York Times, 25 February 1992.

(49) Peter T. Landsberg, “Thermodynamics: Cool Sounds,” Nature, August 1998.

(50) Mark Alpert, “A Cool Idea,” Scientific American, May 1998.

(51) Naomi Lubick, “Desert Fridge,” Scientific American, November 2000.

(52) Alan Hall, “What’s the Beef?” Scientific American, November 1997.

(53) Ammonia Refrigeration, Occupational Safety & Health Administration, U.S. Department of Labor, March 2001

(54) William Murray, “New Technology Developments as a Result of CFC Phase-Out,” Prepared for the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament, 1 April 1992, p. 2.

(55) “Phasing Out CFC-Inhalers – Making the Transition to CFC-free MDIs,” The Green Lane, Environment Canada, July 1999.

(56) “No More Ozone-Depleting Solvents,” Toronto Star, 16 December 1991.

(57) Environment Canada, “Success Stories,” 1997.

(58) Also known as ozone-depleting chemicals (ODCs).

(59) Environment News Service, “Stronger Global Ozone Layer Action Agreed,” December 1999.

(60) Ehsan Masood, “Ozone recovery will be long-term affair,” Nature, Vol. 373, June 1998.

(61) Environment News Service, “China Warms to Fridge Project,” December 1999.

(62) Namrata Singh, “Godrej-GE Appliances to phase out CFC by 2000,” The Financial Express, India, April 1998.

(63) UNEP, Frequently Asked Questions About Ozone to the Scientific Assessment Panel, 2000.

(64) Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, National Action Plan, Environmental Protection Service of Environment Canada, January 1998.

(65) Environment Canada, “The health impacts of living with ultraviolet radiation,” September 1997.

(66) Formerly Atmospheric Environment Services.

(67) Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, National Action Plan, Environmental Protection Service of Environment Canada, January 1998.

(68) “Summary of the 20th Meeting of the Open-ended Working Group of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer: 11-13 July 2000,” Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 7, December 2000.

(69) David Spurgeon, “Ozone treaty ‘must tackle CFC smuggling’,” Nature, Vol. 389, No. 219, September 1997.

(70) Vinod Chhabra, “Montreal Protocol and After,” The Financial Express, India, August 1997.

(71) “11th MOP to the Montreal Protocol and 5th COP to the Vienna Convention,” Linkages, December 1999.

(72) Ibid.

(73) Drew T. Shindell, David Rind and Patrick Lonergan, “Increased polar stratospheric ozone losses and delayed eventual recovery owing to increasing greenhouse-gas concentrations,” Nature, April 1998.

(74) Pearce, “Chill in the air,” 1999.

(75) Peter Aldhous, “Global warming could be bad news for Arctic ozone layer,” Nature, Vol. 404, April 2000.

(76) “11th MOP to the Montreal Protocol and 5th COP to the Vienna Convention,” Linkages, December 1999.

(77) Shindell, Rind and Lonergan, “Increased polar stratospheric ozone losses and delayed eventual recovery owing to increasing greenhouse-gas concentrations,” 1998.

(78) R. Monastersky, “A sign of healing appears in stratosphere,” Science News, 18 December 1999.