88-7E

FEDERAL DEFICIT:

CHANGING TRENDS

Prepared by:

Jean Soucy, Economics Division

Marion G. Wrobel, Senior Analyst

Revised 11 April 2000

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

A. Measuring Deficit Growth: Revenues and Expenditures

1. Operating Deficits

2. Debt

Charges

3. Program

Expenditures

4. The

1991 Federal Budget and the Impact of the Recession

5. The

1992 Federal Budget and Economic Statement

6. The

1993 Federal Budget

7. The

1994 Federal Budget

8. The

1995 Federal Budget

9. The

1996 Federal Budget

10.

The 1997 Federal Budget

11.

The 1998 Federal Budget

12.

The 1999 Federal Budget

13. The 2000 Federal Budget

B. The Growth in the Debt Load

C. The Evolution of Federal Fiscal Policy and the Stability of the Debt

FEDERAL DEFICIT: CHANGING TRENDS*

In fiscal year 1984-85, the Public Accounts deficit of the federal government reached a then unprecedented $38,324 million, amounting to 8.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the corresponding calendar year. Three years earlier, the federal deficit had stood at $14,872 million, or 4.2% of GDP. The federal government finally registered its second consecutive balanced budget in the last complete fiscal year, with a surplus near $3 billion — when measured on a Public Accounts basis. Deficits in the latter part of the 1970s were significantly higher than in the first part of that decade and they ballooned even further in the 1980s and early 1990s. Furthermore, the accumulation of debt, which had declined as a proportion of GDP until the mid 1970s, grew at a rapid pace in the 1980s. As of 31 March 1975, net public debt accounted for 16.8% of GDP. Today, based on Budget 2000, it is just above 61% of GDP, having declined from over 70%.

The Progressive Conservative government put considerable emphasis on its policy of controlling the deficit and debt. The current Liberal government had been committed to reducing the deficit to 3% of GDP by 1996-97 and to 1% in 1998-99. The 1996-97 target was bettered by more than $15,000 million. More important, the federal government has met, and even surpassed, its objectives. With the last surpluses, the government is now predicting another balanced budget, or a small surplus, for 1999-00 and the two following years. This paper examines how these two variables have changed over time, the major influences affecting their size and the fiscal principles through which the federal government hopes to control both.

There are two popular methods of presenting government expenditures and revenues: the Public Accounts (PA) presentation is designed to provide parliamentarians with relevant financial data; the National Accounts presentation is designed to measure the impact of government spending and revenues on expenditure and income flows in the economy. The National Accounts measure of the deficit tends to be smaller than the PA measure. Both, however, have virtually identical patterns over time. The discussion here will consider only Public Accounts data since they are most familiar to parliamentarians. All statistics will be consistent with those of the Budget Papers. For any year cited, the reference is to the fiscal year ending 31 March of that year.

Table 1 presents some of the more commonly cited statistics related to the deficit and debt, expressed in nominal terms. Such numbers can be less than informative, so the following discussion will refer to deficits, debt, etc. as ratios to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

TABLE

1

SOME FEDERAL FISCAL STATISTICS

(in million dollars)

|

Fiscal |

Surplus |

Operating |

Gross |

Net |

|

1970-71 |

-1,016 |

871 |

1,887 |

20,293 |

|

1971-72 |

-1,786 |

324 |

2,110 |

22,079 |

|

1972-73 |

-1,901 |

399 |

2,300 |

23,980 |

|

1973-74 |

-2,211 |

354 |

2,565 |

26,191 |

|

1974-75 |

-2,225 |

1,013 |

3,238 |

28,416 |

|

1975-76 |

-6,205 |

-2,235 |

3,970 |

34,620 |

|

1976-77 |

-6,896 |

-2,188 |

4,708 |

41,517 |

|

1977-78 |

-10,879 |

-5,348 |

5,531 |

52,396 |

|

1978-79 |

-13,029 |

-6,005 |

7,024 |

65,425 |

|

1979-80 |

-11,967 |

-3,473 |

8,494 |

77,392 |

|

1980-81 |

-14,556 |

-3,898 |

10,658 |

91,948 |

|

1981-82 |

-15,674 |

-560 |

15,114 |

107,622 |

|

1982-83 |

-29,049 |

-12,146 |

16,903 |

136,671 |

|

1983-84 |

-32,877 |

-14,800 |

18,077 |

169,549 |

|

1984-85 |

-38,437 |

-16,044 |

22,393 |

207,986 |

|

1985-86 |

-34,595 |

-9,173 |

25,422 |

242,581 |

|

1986-87 |

-30,742 |

-4,074 |

26,668 |

273,323 |

|

1987-88 |

-27,794 |

1,159 |

28,953 |

301,117 |

|

1988-89 |

-28,773 |

4,379 |

33,152 |

329,890 |

|

1989-90 |

-28,930 |

9,859 |

38,789 |

358,820 |

|

1990-91 |

-32,000 |

10,588 |

42,588 |

390,820 |

|

1991-92 |

-34,357 |

6,817 |

41,174 |

425,177 |

|

1992-93 |

-41,021 |

-2,196 |

38,825 |

466,198 |

|

1993-94 |

-42,012 |

-4,030 |

37,982 |

508,210 |

|

1994-95 |

-37,462 |

4,584 |

42,046 |

545,672 |

|

1995-96 |

-28,617 |

18,288 |

46,905 |

574,289 |

|

1996-97 |

-8,897 |

36,076 |

44,973 |

583,186 |

|

1997-98 |

3,478 |

44,409 |

40,931 |

579,708 |

|

1998-99 |

2,884 |

44,278 |

41,394 |

576,824 |

|

1999-00 |

0 |

44,500 |

41,500 |

576,800 |

|

2000-01 |

0 |

46,000 |

42,000 |

576,800 |

|

2001-02 |

0 |

46,500 |

41,500 |

576,800 |

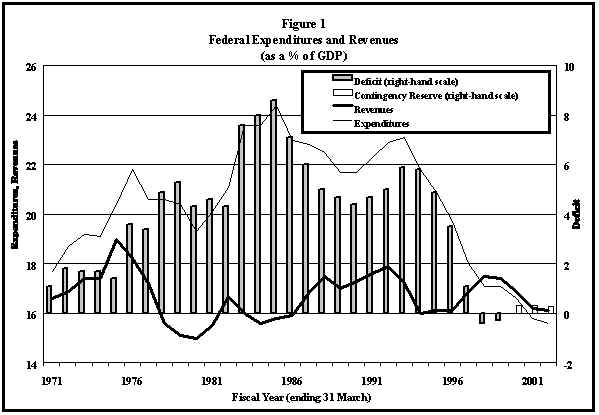

From 1971 to 1975, the PA deficit was less than 2% of GDP. It rose steadily to over 5% of GDP in 1979. After declining for several years it increased sharply to 8.6% in 1985. After the previous federal government made deficit reduction an important part of its fiscal policy, the deficit declined to 4.4% of GDP in 1990. Subsequently, that trend changed. The 1994 deficit grew to 5.8% of GDP, after which it fell sharply, turning to surplus in the last two fiscal years.

A. Measuring Deficit Growth: Revenues and Expenditures

The deficit measures the shortfall of revenues over expenditures in any year. In this sense, it is simply a summary statistic. The changing pattern of the deficit is, then, directly a consequence of changing patterns in revenues and expenditures.

The early 1970s were years of expanding government; federal expenditures rose by an amount equal to almost 3% of GDP, yet, since tax revenues also increased sharply in this short period, the deficit increased only marginally. After 1975, however, taxes fell dramatically, leading total revenues to decline from a high of 19.2% of GDP to a low of 15.2% of GDP in 1980. In 1976, expenditures increased by more than 1% of GDP and then fell by about 2% of GDP by 1980. Such changes in the pattern of expenditures and revenues set the stage for relatively large deficits. By the end of the 1970s, federal expenditures accounted for a greater share of GDP than they had at the start of the decade, even though government growth had moderated. Rather than financing this growth through increased taxes, the government financed it through increased deficits.

From 1980 to 1982, both expenditures and revenues grew slightly, and the deficit was relatively stable. After 1982, the effects of the recession were felt. From then until 1985 revenues declined by about 1% of GDP. Expenditures, however, increased substantially, by more than 3% of GDP, peaking at 24.5% of GDP in 1985. The deficit reduction plans of the previous government included expenditure cuts and tax increases. From 1985 to 1987, tax revenues, which increased by about 1% of GDP, were the primary source of revenue increases. Over the same period, expenditures fell by almost 2% of GDP. The longer-term projections indicated that expenditure reductions were to bear the brunt of deficit cutting.

These patterns are presented in Figure 1. The difference between total expenditures and total revenues constitutes the deficit for each year. Projections beyond fiscal year 1999-2000 contain a contingency reserve, resulting in forecasts of balanced budgets, even though revenues are expected to exceed spending.

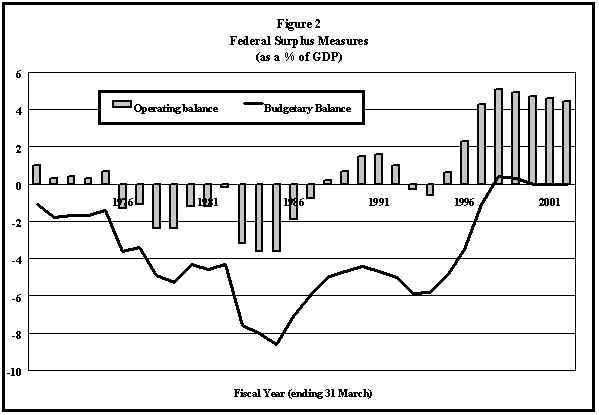

In the 1990 federal budget, the concept of the operating deficit was introduced (see Figure 2). The operating deficit is the difference between program spending and total revenue. It can also be calculated as the total deficit less gross debt charges.

Until 1978, changes in the deficit were directly related to changes in the operating deficit, which, for the next few years, fell much faster than the total deficit. Debt charges were becoming an increasingly important factor in determining the growth of the deficit.

From 1982 to 1983 the deficit rose sharply, largely in response to the recession. Figure 2 indicates that an increase in the operating deficit was largely the cause. After 1983, it is clear that the operating deficit was becoming less influential on the budgetary deficit of the federal government while debt charges were becoming more so.

The operating deficit is more sensitive than the total deficit to changes in the government’s fiscal stance, and to changes in economic conditions. After the previous government was elected, the operating balance fell continually, going into surplus in 1988. The recession generated an operating deficit once again. Since 1998, it has moved to a surplus of around 5% of GDP.

The debt charge in any year is determined by the average stock of debt outstanding, multiplied by the average interest rate applied to that debt. Some of the debt has a long term to maturity and the interest rates for that component may be much higher than prevailing rates. Newly issued debt, however, will have interest rates that reflect current market conditions. The faster the increase in the stock of debt, the greater will be the proportion of it subject to prevailing interest rates.

The net debt outstanding at any time is simply the sum of past deficits on a PA basis. This amount, plus the amount of borrowing to acquire financial assets, gives the gross debt total. Debt charges are therefore related both to current interest rates, usually cited in discussions of the deficit, and to past deficits, usually downplayed. If the federal debt comprises long-term fixed rate debt, however, a sharp rise in interest rates will have little immediate impact on net debt charges in a world of low deficits because only small amounts of new debt have to be financed at current rates. With large deficits, however, a large new stock of debt must be financed, and at prevailing rates.

A debt load that is rapidly growing as a result of high annual deficits, then, makes the budgetary stance of the government more sensitive to temporarily high interest rates because a higher proportion of the debt is subject to prevailing interest rates.

Total expenditures, less debt charges, constitute total spending on government programs. It is, of course, spending on such programs that is at the heart of modern government. During the heyday of government expansion, 1971 to 1976, it was the increase in program spending which led to overall spending growth. In 1971, program spending amounted to 15.6% of GDP and 87.9% of total federal spending; at its peak, in 1976, it amounted to 19.5% of GDP and 89% of total spending.

Since then, program spending’s share of total outlay has declined. Even during the recession, it did not achieve the relative share it held in 1976. Program spending fell to about 75% of total spending by 1989. Since 1998, it has represented less than 73% of total spending and should fluctuate between 71.5% and 72.5% by 2001-2002. In that year, program spending should equal only 11.6% of the GDP.

Program expenditures can be further disaggregated in a number of ways. In past federal budgets, the Department of Finance has divided expenditures into statutory and non-statutory expenditures. In 1985, statutory expenditures accounted for 55.4% of total program expenditures and by 1989, were expected to rise to 57.9%.

No such disaggregation is available for the years before 1984; changed accounting definitions make a longer-term series potentially misleading. Nevertheless the major statutory expenditures are obvious: UIC benefits, OAS benefits, Family Allowances, Canada Assistance Plan, the cash portion of Established Programs Financing and fiscal transfers. According to a Bank of Canada study, most of the increase in expenditures before 1984 can be accounted for by increased spending on statutory programs. As is evident from budgetary statistics, this trend has continued since 1984.

4. The 1991 Federal Budget and the Impact of the Recession

With the onset of the recession, the federal government had to revise some of its fiscal projections. The deficit for 1990-91, forecast in 1990 at $28,500 million, was now expected to total $30,500 million. For 1991-92, the picture was even gloomier. In the 1990 budget, the government had been predicting a declining deficit of $26,800 million. In 1991, despite new initiatives to control the deficit, amounting to $4,500 million in spending cuts and increased taxes, the deficit was still expected to remain at $30,500 million. In other words, the recession and Gulf hostilities had led to a 30% increase in the status quo 1991-92 deficit.

5. The 1992 Federal Budget and Economic Statement

The 1992 budget increased the deficit projections for 1991-92 by $900 million and for 1992-93 by $3,500 million. Despite the fact that public debt charges had fallen with the decline in interest rates, the recent poor economic performance had dramatically increased the upward pressure on the deficit. This was moderated somewhat by policy actions. As a consequence, the Department of Finance had predicted that the debt-to-GDP ratio would continue to rise for another year, peaking at about 63% of GDP; it now appeared that it would continue to rise to over 65% of GDP. By 31 March 1994, the net debt of the federal government was expected to be $20,000 million more than had been projected at the time of the 1992 budget.

Once again, the federal government had failed to achieve its deficit targets. The estimate for 1992-93 was now $35,500 million, $1,100 million higher than expected in December 1992. Cumulative deficits from 1992-93 to 1996-97 were now expected to be $53,600 million higher than had been forecast in the 1992 budget.

The deficit picture painted in the 1993 budget closely resembled those presented in previous budgets, with substantial rapid declines expected two or three years ahead. These forecasts had so far always failed to be realized: in the 1980s, unexpectedly high interest rates had foiled the government’s plans; in 1993, unexpectedly low revenue yields were responsible.

Some suspected that the move to a world of low inflation had had a negative impact on the deficit, at least temporarily. Since most program spending is set without regard to inflation or nominal GDP, an unexpected reduction in inflation would not reduce the bulk of program spending. Revenues, on the other hand, decline directly with reduced inflation because of its effect on nominal GDP. Moreover, since the tax system was not perfectly indexed to inflation, lowering the rate of inflation below 3% had an added revenue-contracting effect as the government lost the full effect of the inflation tax.

The government’s deficit reduction strategy was based upon: (1) strong economic growth starting in 1993, which was supposed to boost revenues; (2) control of program expenditure; and (3) reduced interest rates to keep the debt servicing burden almost constant despite the growing net debt. This budget saw continuing declines in interest rates because of continued low inflation and revenue growth, which was expected to result from real output growth of over 4% per year through to 1998; employment growth in excess of 3% per year, and an unemployment rate falling to 7.5% by 1998. It was recognized that failure to meet these goals could derail the government’s forecasts.

The 1993 federal budget forecast deficits for 1992-93 and 1993-94 at $35,500 million and $32,600 million respectively. The 1994 budget gave figures of $40,500 million and $45,700 million respectively; the two-year increase in net debt amounted to $18,000 million. Despite the $5,000-million increase in the deficit for 1992-93, financial requirements had increased by only $100 million from the amount cited in the budget; financial requirements for 1993-94, however, were up by over $7,000 million.

The budget indicated that, in the absence of policy changes, deficits would be substantially higher over the next few years than had been forecast by the previous government. Economic and technical factors were expected to increase the cumulative debt by $39,000 million from 1993-94 to 1995-96. It was claimed that the Progressive Conservative government’s failure to pass legislation proposed in past budgets would contribute an additional $5,300 million to the cumulative debt over the same period.

By 31 March 1996, the net debt was expected to equal 75% of GDP. The 1992 budget had predicted that it would equal only 55% of GDP by that date.

The 1992-93 federal deficit, according to the 1993 budget, was $35,500 million. It turned out to be $41,000 million and grew further to $42,000 million the year after. In 1994-95 it fell to $37,900 million (and it could have fallen even further, to $35,300 million). The figure was inflated because of two restructuring costs charged to the 1994-95 year: an ex gratia payment of $1,600 million to western farmland owners in compensation for the elimination of the Western Grain Transportation Act subsidies and $1,000 million for early departure incentives for public servants. The deficit was projected to continue falling to $24,300 million in 1996-97, meeting the government’s stated interim target of 3% of GDP.

The 1995 budget focused on deficit cutting. Over a three-year period, measures implemented in this budget were expected to keep the cumulative deficit $29,000 million below what it would otherwise have been. Expenditure cuts in this package were about seven times greater than revenue increases. In the first year the ratio was closer to 4:1.

This short-term deficit decline was enhanced by the government’s decision to allow the UI Account to generate more than a $5,000 million surplus, prior to allowing UI premiums to decline after 1996. The purpose was to avoid increasing premiums during an economic downturn, when the account would normally go into deficit.

The deficit projections for 1995-96 and 1996-97 contained contingency reserves of $2,500 million and $3,000 million respectively. These reserves were designed to provide the government with a buffer in the event that economic conditions, in particular interest rates, did not turn out to be as favourable as predicted. In other words, the government’s model, given its economic assumptions, generated better deficit results than those cited in the budget. Indeed, when combined with the fact that the economic assumptions used by the government were more pessimistic than those of private sector forecasters, the underlying deficit projected for 1996-1997 was about $19,000 million, rather than the $24,300 million figure cited in the budget.

The 1995 budget did not provide a forecast of the 1997-98 deficit, even though it did include estimates of the impact of budgetary measures for that year. Indeed, 46% of the deficit cutting measures were to be effective in 1997-98. Thus it was predicted that the deficit for that year could be under $18,000 million, amounting to as little as 2% of GDP, something that had not been seen for 20 years and that was expected to result in a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

At 31 March 1993, the net public debt stood at $466,200 million, compared to $358,000 million in 1990 and in contrast to the $428,000 million that the 1990 budget had forecast for 1993. By 31 March 1997, it was expected to reach $603 million. Over the next two years the net debt was expected to stabilize at about 73.5% of Gross Domestic Product.

Public debt charges were expected to exceed $50,000 million by 1996-97, due to both the continually increasing debt and rising interest rates. Short-term interest rates for 1995, for example, were projected to be 8.5%, compared to the 4.8% projected in the 1994 budget.

The impact of debt accumulation and high debt servicing costs was very evident in the projections presented for 1996-97. For that year, the government was forecasting a deficit of $24,300 million at the same time that it was anticipating an operating surplus (i.e., an excess of revenues over program spending) amounting to $29,000 million, by far the highest ever recorded. Balancing the budget several years after that would require operating surpluses in excess of $50,000 million per year. This is a perfect example of the consequences of spending not financed by current taxes. Clearly, deficit financing does not avoid tax financing of expenditures, it merely defers that taxation.

The government maintained in this budget that it would meet its 1995-96 deficit target of $32,700 million, although there was a strong chance that the final result would be somewhat lower. The deficit target of $24,300 million for 1996-97 was also maintained and a $17,000 million target was formally established for 1997-98. Several analysts contended that the deficit would fall below these targets as well.

The poor performance of the economy in 1995 had resulted in revenues that were lower than predicted in the budget of 1995. This was offset by the lower interest rates that had kept debt service charges from growing as rapidly as originally anticipated. The operating surplus continued to grow, although at a slower pace than had been expected the year before, and was expected to reach $35,000 million by 1997-98, amounting to 4.2% of GDP.

The Minister of Finance stated several times in his budget speech that the government would balance its budget, so the targets could be seen as interim. Given the pattern of deficit reduction since 1993-94, it was hoped that a target for a balanced budget could well be established for the fiscal year 1999-2000. Indeed, the forecasters who appeared before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance during its pre-budget consultations generally believed that budgetary balance should be achieved no later than that date.

Federal budget-making continued to be cautious, using prudent economic assumptions plus a contingency reserve to protect against unforeseen events. Thus revenue and spending measures were a little stronger than necessary, ensuring that targets would be met. Interest rate assumptions were 50 basis points higher than the private sector average forecast for 1996 and 80 basis points higher for 1997. (The budget attributed the larger prudence factor for 1997 to the compelling arguments made by the Finance Committee about higher political risk in 1997.) As a result, the budget’s growth assumptions were slightly below those of the private sector, which were already low. The use of private sector economic assumptions generated a forecast deficit closer to 1.5% of GDP, as contrasted with the 2% target. Furthermore, measures introduced in the 1996 budget suggested that the 1998-99 deficit could be close to 1% of GDP, barring any unforeseen deterioration in the economy and barring any increase in interest rates.

It appeared on the surface that the Minister of Finance could set a 1% deficit target for 1998-99, consistent with past practice, requiring only about $3,000 million or so in additional restraint measures. The Minister faced a very real difficulty, however. The government was currently using employment insurance premiums well above those needed to meet annual program costs, as revenue to reduce the deficit. The justification for this was the fact that, in the early 1990s, what was then called the UI account had amassed a large cumulative deficit that still stood at $3,900 million as of 31 March 1995. The 1995 budget had proposed that the government would keep premiums above those needed to meet annual costs so as to allow the account to pay off the past accumulated deficit and amass a cumulative surplus somewhat in excess of $5,000 million by the end of 1996; this surplus would then be maintained. This was interpreted as meaning that premiums would subsequently be reduced to a level commensurate with annual costs.

Strong pressure came from the private sector to let premiums fall, so that employers and employees could enjoy the benefits of declining program costs. Rates were reduced, albeit very modestly, and the premiums for 1997 were to be set tin the fall of 1996. The budget’s revenue and spending outlook tables, however, suggested that the fund would continue to enjoy a large annual surplus in 1997-98. The cumulative surplus could then be twice as high as that suggested in the 1995 budget.

It was known that if employment insurance premiums were reduced substantially for 1997, the revenue outlook presented in the budget would be put in doubt. If the 2% target for 1997-98 was to be sacrosanct, the loss in premium income had to be offset elsewhere -- the shortfall could not be funded by the contingency reserve. Other taxes would have to be increased or further spending cuts sought. Thus there were potentially some difficult decisions for 1997-98. They could only be avoided by maintaining premiums and allowing the account to continue to amass a cumulative surplus of about $10 billion by the end of 1997-98.

In addition, the government altered the timing of employment insurance premium payments to make it consistent with that for CPP premium payments. Until then, weekly premiums had been based on the lesser of maximum insurable earnings or actual earnings. As of January 1997, weekly premiums would be based upon actual weekly earnings; once the maximum annual premiums were reached, further premium payments would cease. Those who earned maximum insurable earnings or less would continue to pay premiums over a 52-week period. Those who earned more would pay their premiums over a shorter period of time. Someone earning $80,000 per year would pay all of the premiums in the first half of the year and pay nothing in the latter half.

This administrative change had no effect on total premium liabilities of employees and employers. But the timing change did affect the reported government deficit. By advancing premium payments, starting in 1997, the deficit for 1996-97 was expected to be $1,500 million to $1,800 million less than stated in the budget. The impact on future fiscal years would be neutral. Nevertheless, this one-time administrative change had the potential to reduce future debt servicing costs by about $100 million per year.

The budget also did not take into account proceeds from the sale of assets in 1996-97, in particular the sale of grain hopper cars and the air navigation system. The budgetary impact of these sales depended upon the amount received as well as the accounting treatment of the assets. Newspaper accounts at the time suggested that the gains from sale could be $1,500 million.

While the federal government was able to establish an achievable deficit target for 1997-98 (2% of GDP), it was recognized that further difficult choices could not be avoided if the budget was to be balanced by the end of the millennium.

The fact that the Minister could announce a 2% target for 1997-98 yet introduce deficit-cutting measures that, on balance, amounted to less than $200 million, indicated that the previous year’s budget had been responsible for that target. The 1996 budget’s impact would really be felt only in 1998-99, and only modestly then.

The casual reader of the budget might have inferred that economic growth in 1996 should decline. Given the fact that 1995 was generally acknowledged to be a bad year, this conclusion might have been disconcerting and, since most analysts were predicting a better year for 1996, also confusing.

The growth assumptions in the 1996 budget were based on a comparison between the average GDP in one year and average GDP in the preceding year. Thus some of the strong performance in 1994 was attributed to a 2.2% growth rate in 1995, and some of the poor performance in 1995 was attributed to a predicted 1.8% growth in 1996. A look at growth achieved during a calendar year showed that the growth rate for 1995 had been 0.6% and the expected rate for 1996 was 2.5%, a rate four times higher.

Unlike previous budgets, this one did not continue to insist that the deficit target for the current fiscal year, i.e. 1996-97, would be met. Instead, it announced that, at $19,000 million (2.4% of GDP), the deficit would be at least $5,300 million below the target. Indeed, some speculated that the final tally could be lower still.

The Department of Finance’s Fiscal Monitor showed a $2,191-million surplus for December 1996 and a cumulative deficit for the first nine months of the fiscal year that was $13,185 million less than that of the year before, which eventually came in at $28,600. The document cautioned readers not to draw overly optimistic conclusions from these trends as past government initiatives had altered the timing of revenues and expenditures over the course of the fiscal year. Revenues to date had also been affected by one-time events such as the sale of the air navigation system.

Another change from previous budgets was the fact that the contingency reserve for the upcoming fiscal year was kept at $3,000 million, rather than being reduced to $2,500 million as had been the case in the past.

This budget introduced a variety of measures that were likely to increase the debt by a total of $3,400 million over four years. The $19,000-million deficit figure for the year could have been $18,200 but for the $800-million cash infusion into the Canada Foundation for Innovation. Other measures, some announced prior to the budget under the headings "Investing in Jobs and Growth" and "Investing in a Stronger Society," were expected to add to spending over the next three years. These new initiatives were to be funded in part by reallocations from other areas and higher taxes (e.g., tobacco excise tax increases and an extension of the temporary tax on banks), but mostly from borrowing. Despite these new measures, however, program spending was still falling as planned and future deficit targets were not in jeopardy.

The budget outlined why the deficit fell below the target expressed in the previous year’s budget. Revenues, with the exception of the Corporate Income Tax, were generally lower than predicted by that budget -- on balance they were $2,000 million lower. Program spending was $800 million lower than forecast while public debt charges were $2,300 million lower because interest rates had declined rapidly during the year. In total, these economic factors reduced the deficit by $1,100 million.

One-time factors, such as the sale of the air navigation system and the acceleration of EI premium collections, contributed another $2,500 million to deficit reduction. Since neither of these was a new initiative, however, it could be argued that both should have been taken into account in the budget of the previous year. This was especially true of the acceleration of EI premiums, whose impact should not have been difficult to estimate. The sale of the air navigation system was somewhat more problematic, as the date of the deal’s closing could have been subject to uncertainty.

Finally, the government did not need to make use of the contingency reserve, thereby saving another $2,500 million. When added to the newly announced $800-million contribution to the Canada Foundation for Innovation, these factors were expected to lead to a deficit at least $5,300 million below target. At the time of the budget, however, three months remained in the fiscal year, and no data were available for the end-of-year reconciliation. As a result, it was known that the deficit could still fall below $19,000 million.

This budget also acknowledged the improved fiscal position of most Canadian provinces. As with the federal government, the fall in provincial deficits was largely due to reduced program spending, coupled with the benefits associated with lower interest rates. The budget noted that the reduction in interest rates from January 1995 to December 1996 had saved provincial governments a total of $1,800 million, equal to 1.2% of spending. Although Canada still had a debt-to-GDP ratio that was exceeded only by Italy’s among the G-7 nations, our total government deficit was expected to be the lowest in the G-7 starting this year. It was predicted that, as of 1998, Canada would be the only G-7 nation to have a balanced government account when measured on a national accounts basis. This compared favourably with American deficits of more than 1.5% of GDP, German and Japanese deficits of more than 2% of GDP, and deficits in France, the United Kingdom and Italy of 3% or more of GDP.

This budget continued the government’s use of prudent economic forecasting -- it added 80 basis points to the private sector average for three-month Treasury Bills and 50 basis points to the private sector average for 10-year government bond rates. The government’s forecast for growth was 3.2% in 1997, declining to 2.65% in 1998.

The fiscal year 1996-97 was expected to mark the end of the continual growth in the debt-to-GDP ratio. That ratio was expected to start its decline, resulting in a fall to 73.1% of GDP, down from the peak of 74.4%.

In this budget, the Minister of Finance projected that the budget would be balanced in that fiscal year (1997-98), and that the same would hold true for the next two years of the budget planning cycle. In fact, he did better than he announced; a $3.5 billion surplus was achieved in 1998, something unprecedented in the modern fiscal history of the federal government. According to the budget, the net debt fell to 67.8% of GDP in 1998.

The better-than-expected performance came from $10,000 million in tax revenues above what was anticipated in the previous year’s budget. Much higher corporate income tax receipts and GST revenues accounted for most of this. Program spending was down $3,000 million from the previous year’s projections, largely due to lower EI benefits. Public debt charges were lower than expected, and the $3,000 million contingency reserve was not needed.

In accordance with the recommendations of the Auditor General, the government revised the way it recorded interest costs associated with public sector pension plans. This reduced interest costs by about $0.6 billion in 1998. With the budgetary surplus, the federal government was able to decrease the public debt. This debt passed from $583.2 billion in 1996-97 to $579.7 billion in 1997-98 — the first reduction since 1969.

The government used prudent economic assumptions to avoid the effects of the Asian financial crisis, which touched three-fifths of all countries in the world. This step, together with its use of a contingency reserve of $3 billion that year, gave the government a $6-billion cushion each year. If recent history is any guide, the use of prudent budgeting practices should mean a net debt in 1999-2000 closer to $571 billion than the peak of $583.2 billion in 1997. Thus, the net debt-to-GDP ratio would be closer to 61% than the 63% cited in the budget. The government has taken prudence to new heights for 1999.

In the past, the government added 80 basis points to the private sector average forecast for short-term interest rates in order to arrive at its prudent assumption; for long-term interest rates, it added 50 basis points. The 1998 budget added 100 basis points to both the short- and long-term interest rates when making its prudent interest rate assumption.

The 1998 budget was balanced (and in fact had a surplus) and the 1999 budget continued this trend. The federal government expected that the budget would be at least balanced until 2000-01. The net debt was expected to stay at almost the same level as this year’s $579.1 billion, amounting to 65.3% of GDP, with expectations for 62% of GDP for the 2001 budget.

If claims of a balanced budget proved to be well founded, the $3-billion Contingency Reserve was to be used to reduce the public debt. Ever since 1995-1996, the debt-to-GDP ratio had been decreasing. This unusual situation was almost exclusive to Canada among the G-7 countries with the notable exception of the United States. The federal government was aware that it would have to maintain its prudent approach to budgets in order to stay on this path.

The fiscal year that ended in 1999 showed a second consecutive surplus, although, at $2.9 billion, it was slightly smaller than that of the previous year.

The federal government continues to forecast balanced budgets until 2001-02. It does not issue forecasts over a longer period, however, even though the Economic and Fiscal Update 1999 contained five-year projections for public debate purposes.

As stated in the November 1999 update, the federal government will use an economic "prudence" reserve, in addition to the existing $3-billion contingency reserve. This was confirmed in Budget 2000. The federal government forecasts balanced budgets from 1999-00 until 2001-02. The net public debt, $576.8 billion in 1999 and standing at 64.4% of the GDP, is expected to remain at this nominal level over the same period. Thus, the net-public-debt-to-GDP ratio would amount to 55.2%, which is expected to fall to under 50% in 2004-05.

If the contingency reserve proves not to be needed and is used to pay down the debt instead, the nominal debt level would fall to $567.8 billion, 54.3% of GDP. Even at this level, this ratio would continue to be higher than the average of G-7 countries.

Budgetary revenues are expected to increase by 2.8% in 1999-00, falling to 1.3% in 2000-01 as a result of tax relief measures announced in the Budget. Budgetary revenues would experience stronger growth in 2001-2002.

Program spending is expected to rise by 3.7% in 1999-00, largely because of the $2.5-billion CHST cash supplement and $1.3 billion for initiatives to make the economy more innovative. If the federal government introduces no additional initiatives, program spending will increase by only 0.4% in 2000-01; however, a sharper increase (4.7%) is already forecast for 2001-02.

Public debt charges are expected to fluctuate around $42 billion until 2001-02. The debt is less sensitive to interest rate changes because of the increased proportion of fixed-rate debt.

B. The Growth in the Debt Load

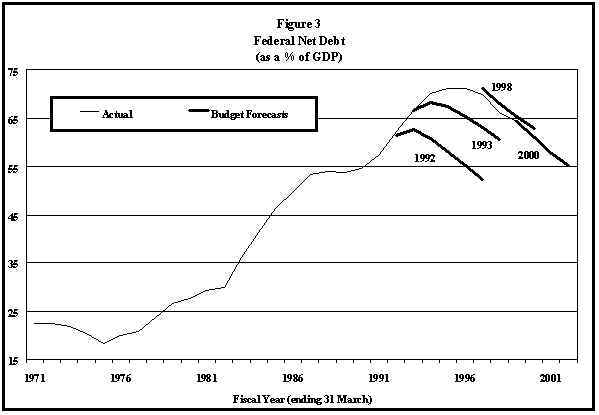

For the two decades ending in 1975, federal net debt had been slowly declining as a proportion of GDP. It reached a low of about 17% in 1975, as compared with 36% in 1956. (During World War II it had exceeded 100% of GDP but this percentage was quickly reduced after the war.) Since 1982, net debt has grown by an amount equal to almost 40% of today’s GDP.

The level of net debt equals the cumulative total of past deficits on a Public Accounts basis. It is, then, a stock measure of past annual flows. Net debt therefore provides an alternative view of annual government deficits and might be useful in generating other perspectives on fiscal policy.

Figure 3 highlights the rapid growth of federal government net debt in the 1980s. As at 31 March 1982 it stood at 28.25% of GDP. By 31 March 1987 it had reached 51.8% of GDP, as a result of the very high annual deficits experienced in the intervening years. It peaked at about 72% of GDP in 1995-96, before slightly declining.

The relationship between debt growth and deficits can be demonstrated by the following relationship:

(1) The change in (Net Debt/GDP)

= (Operating Deficit)/GDP

+ (Net Debt/GDP)*(interest rate - GDP Growth)

The ratio of debt to GDP increases directly as a result of the ratio of operating deficits to GDP. The increase is also related to the ratio of existing debt to GDP, multiplied by the difference between the interest rate charged on the debt and the growth rate of GDP. If the interest rate charged on outstanding debt is equal to the rate of GDP growth, then the debt-to-GDP ratio can be stabilized by financing all program spending through taxes: i.e., running a zero operating deficit. If the interest rate charged on outstanding debt exceeds the rate of GDP growth, then an operating surplus must be realized for stabilization. To reduce the ratio of debt to GDP, even larger operating surpluses must be achieved.

It is useful to examine this relationship between the ratio of debt to GDP, the operating deficit, interest rates and GDP growth in order to translate the fiscal principles guiding this government into deficit constraints.

These conclusions about the primary deficit say nothing about the overall size of the deficit which would be needed to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. This would depend upon the target debt ratio set by the federal government. To maintain a stable debt ratio, the following relationship would hold:

(2) Deficit/GDP = (Debt/GDP)*GDP Growth

If the debt-to-GDP ratio is 75% and GDP is growing at 5% per year, a deficit equal to 3.75% of GDP will stabilize the debt ratio. If the debt-to-GDP ratio is only 25%, the deficit cannot exceed 1.5% of GDP. A 1985 paper on the deficit issued by the Minister of Finance proposed another fiscal goal: to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio to no more than 25% of GDP, a level that existed prior to the 1980s.

Figure 3 also highlights the performance of forecasts of the debt-to-GDP ratio. At the beginning of the last decade, forecasts always underestimated the actual figures, while in the most recent budgets the forecasts have overestimated them.

Once such a long-run target debt-to-GDP ratio is achieved, it can be maintained by running deficits which do not exceed about 1.25% of GDP, based on a 5% growth rate. But, though it could maintain it, such a deficit would not be enough to achieve that target in the first place. For example, if interest rates match GDP growth rates, the debt ratio can be reduced by three percentage points per year by running an operating surplus equal to 4% of GDP. Many analysts were suggesting a more modest short-term goal of reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio to about 60%. Such a target could reasonably be achieved within five years. Based on Public Account figures, the debt-to-GDP ratio would reach the 60% level in fiscal year 2000-01.

C. The Evolution of Federal Fiscal Policy and the Stability of the Debt

The federal net debt is now declining as a proportion of GDP. This decline is substantial and is expected to continue for a number of years, reversing much of the two-decade increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. It might be useful to examine the factors that have determined the trends in this ratio.

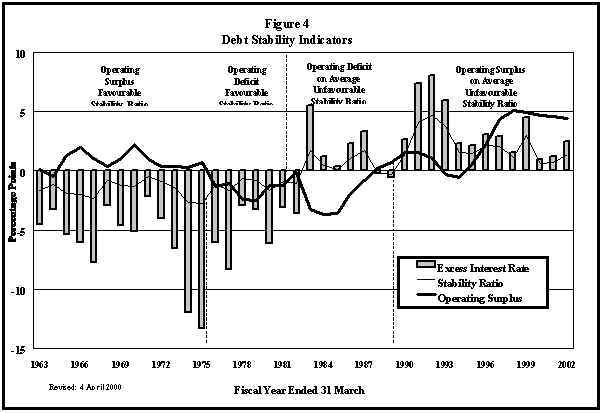

Figure 4 presents federal fiscal policy and economic conditions since 1963. This chart plots three variables: 1) the excess interest rate, which is the difference between the average interest rate on federal government debt and the rate of growth of the economy; 2) the stability ratio, which is defined as the excess interest rate multiplied by the net debt-to-GDP ratio; and 3) the operating surplus of the federal government, expressed as a percentage of GDP. The operating balance is the difference between total revenues and program spending. The stability ratio indicates the operating balance, expressed as a percentage of GDP, that is needed to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio constant. If the operating balance is higher, the net debt-to-GDP ratio will fall.

From these variables, we can distinguish four periods, as determined by economic conditions and fiscal policy stance.

Period A: Until the mid-1970s, the economy generated growth rates that substantially exceeded the rate of interest paid on government debt. This meant that the federal government could have run operating deficits while still stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio over time. But the government did the contrary. It ran operating surpluses and, consequently, the debt-to-GDP ratio fell. One could say that this was a period in which government fiscal policy was prudent and economic conditions were favourable. The federal government borrowed on an annual basis, but in order to finance only part of its debt servicing costs. By the last few years of this period, however, federal fiscal policy was starting to become significantly looser.

Period B: From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, economic conditions continued favourable. Economic growth continued to exceed interest rates and hence the stability ratio was still negative. The fiscal stance of the federal government deteriorated, however. It started, on a regular basis, to run operating deficits that were, on balance, large enough to cause the debt-to-GDP ratio to rise slowly. The federal government was now borrowing to finance all its interest costs as well as some program spending. The post-war trend in the net debt-to-GDP ratio had finally reversed.

Period C: From early in the decade to about 1988, fiscal policy became even looser than in the previous period, although by mid-decade that trend had been reversed. Nevertheless, operating deficits were larger than in the previous period, in part due to the recession. The turnaround in economic conditions would exacerbate the effect of looser fiscal policy. The stability ratio turned positive as interest rates exceeded the rate of growth. Thus, the government had to run operating surpluses in an attempt to stabilize the debt. Stabilization was not achieved, however, and the debt-to-GDP ratio increased rapidly.

Period D: As we entered the new decade, interest rates were still exceeding economic growth by quite a large margin. This situation, coupled with the high net debt-to-GDP ratio that resulted from the deficits of the 1980s, meant that very large operating surpluses were required to stabilize the debt. Although fiscal policy in the first half of the 1990s was clearly tighter than in the past, it was not sufficient to stabilize the debt ratio. The change in fiscal policy was too little and too late.

The latter half of the 1990s is in a sense a distinct period. The stability ratio has declined substantially on account of falling interest rates and improved growth. It remains higher than during period C because the excess interest rate is applied to a large stock of net debt. The operating surplus has grown substantially and finally stands at a higher level than the stability ratio. With strong growth and absolute declines in the net debt, the ratio of debt to GDP is falling substantially, from 71.2% in 1995-96 to an expected 55% in 2001-02. Balanced budgets are generating an operating surplus equal to about 5% of GDP, which is well above that needed to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio.

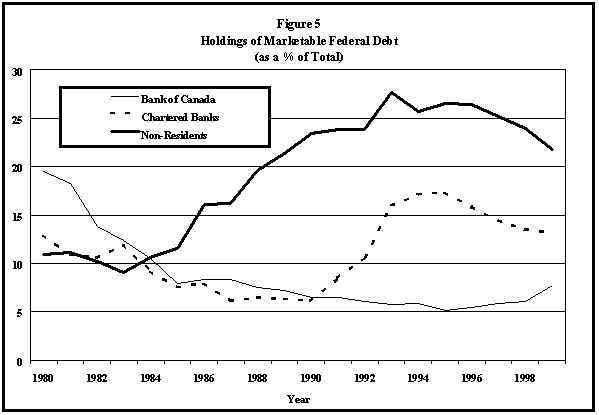

Figure 5 highlights the changing nature of the groups holding Government of Canada marketable debt. There are two rather dramatic trends. The Bank of Canada significantly reduced its importance as a holder of government debt in the 1980s. The absolute amount of its debt holdings increased from $16,000 million in 1980 to more than $27,000 million. This represents less than 6% of the total, compared to 19.5% in 1980. The other dramatic change was the increase in holdings by foreigners since 1984, although the share declined steadily since 1993. Foreigner now hold nearly 22% of the debt (about $100,000 million), up from 11% in 1980.

Since 1990, a new trend has become evident, whereby chartered banks hold ever-increasing amounts of federal government debt. From 1990 to the end of 1995, holdings more than trebled, to near $80,000 million. Chartered banks held over $60,000 million of federal debt as of the end of 1999.

The size of the federal deficit is affected every time the federal government undertakes some spending measure or alters the system of taxation. Virtually all government measures therefore affect the deficit. Approximately once every year, the Minister of Finance presents a budget in which the government’s future spending and taxation plans are outlined.

June 1971 - The UI system was substantially expanded and liberalized with the passage of Bill C-229.

January 1974 - Family allowance payments were increased to $20 per month per eligible child and began to be considered as taxable income. The monthly payment also became subject to indexation.

1977 - Bill C-27 was passed to tighten up the liberalized UI system. It increased eligibility requirements and reduced maximum weeks of benefits for a wide range of UI recipients.

1978 - The Child Tax Credit was introduced. The maximum benefit was set at $200 per eligible child.

1979 - Family allowance benefits were reduced by about 22% starting in January.

1983 and 1984 - Indexation factors for government expenditures were limited to 6% and 5% respectively for these two years.

May 1985 - The federal budget limited indexation to CPI increases greater than three percentage points. This partial indexation applied to a wide variety of tax measures and some social programs.

June 1987 - The federal government tabled its White Paper on tax reform. This reform was designed to alter the distribution of tax liabilities between taxpayers and types of income. It was to be revenue-neutral and so have no direct effect on the deficit.

December 1987 - The federal government announced its National Strategy on Child Care which proposed an enhanced Deduction for Child Care Exemptions, an increased Child Tax Credit for families without receipts for child care expenses, and new cost-sharing arrangements with the provinces. These measures were expected to cost the federal government $5,400 million over the next seven years.

February 1991 - The federal budget announced legislated limits on future program spending as well as the establishment of a Debt Servicing and Reduction Fund into which all GST revenues would flow.

November 1993 - The Department of Finance calculated that the 1992-93 deficit would be $40,500 million, $5,000 million higher than stated in the 1993 budget.

- The Minister of Finance estimated that the 1993-94 deficit would be between $44,000 million and $46,000 million. This was as much as $13,400 million higher than the amount predicted in the 1993 budget.

February 1994 - The first Liberal budget predicted that the 1993-94 budget deficit would reach $45,700 million. The government still maintained that it would be able to reduce the deficit to 3% of GDP in three years.

October 1998 - Many months after the 1998 budget, Finance Minister Paul Martin announced the first balanced budget since the 1970s and a surplus of $3.5 billion.

November 1999 - After a second balanced budget, Finance Minister Paul Martin announced a five-year plan for forecasting purposes. The cumulative surplus was expected to reach $95 billion over that period.

Bloskie, C. "An Overview of Different Measures of Government Deficits and Debt." Canadian Economic Observer, November 1989, p. 3.1-3.20.

Canada, Department of Finance. The Fiscal Plan. Ottawa, various issues.

Canada, Department of Finance. The Federal Deficit in Perspective. Ottawa, April 1983.

Canada, Department of Finance. Reducing the Deficit and Controlling the National Debt. Ottawa, November 1985.

Canada, Department of Finance. Tax Reform 1987. Ottawa, June 1987.

Canada, Department of Finance. Debt Operations Report. Ottawa, September 1994.

Canada, Department of Finance. A New Framework for Economic Policy. Ottawa, 1994.

Canada, Department of Finance. Annual Financial Report of the Government of Canada. Ottawa, 1994.

Canada, Department of Finance. The Economic and Fiscal Update. Ottawa, 1994.

Canada, Department of Finance. The Economic and Fiscal Update. Ottawa, 1999.

"Federal Government Revenues, Expenditures and Deficits Since 1970." Bank of Canada Review, October 1985.

Mimoto, H. and P. Cross. "The Growth of the Federal Debt." Canadian Economic Observer, June 1991.

Prince, M.J. How Ottawa Spends, 1987-88: Restraining the State. Methuen, Toronto, 1987.

* The original version of this Current Issue Review was published in March 1988; the paper has been regularly updated since that time.