|

BP-320E

FEEDING THE WORLD'S

HUNGRY:

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS FOOD SUPPLY AND THE DIMINISHING RESOURCE BASE THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER HOW DO DEVELOPED COUNTRIES RESPOND? AGRICULTURE AS THE BELLWETHER MEASURE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH

FEEDING THE WORLD'S

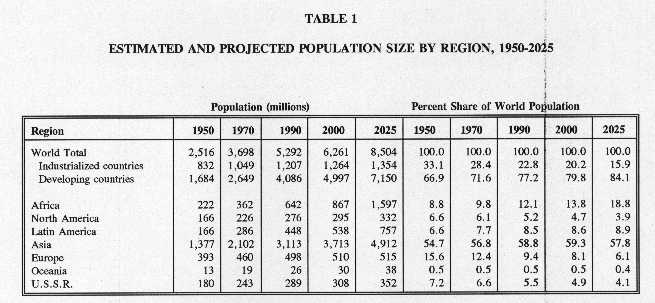

HUNGRY: The prospects for achieving satisfactory global living standards are threatened by environmental deterioration, especially in the poorest countries, where agricultural and other economic activities are most heavily dependent upon the quality of natural resources.(1) Some of the environmental changes that are taking place as a result of efforts to improve standards of food, clothing, shelter, comfort and recreation have the potential to do irreversible damage to the earth's capacity to sustain life. Meanwhile, unrestrained population growth in some developing countries is exacerbating the deterioration of the environment. Past scientific and technological innovations in agriculture were able to overcome resource constraints. It is questionable, however, that agricultural productivity can keep pace with a rapidly growing population while protecting our global resources and ensuring that they will provide enough food for generations to come. The paper looks at the role of developed countries in promoting agricultural self-reliance in the Third World by the transfer of skills and "appropriate" technology. It explores methods of measuring human progress using agriculture as an indicator of the health of our planet. It suggests that current methods of evaluating prospects for the world's food supply are inadequate. In A.D. 1, the world supported about 300 million people. More than 1,500 years passed before the population doubled. In the 18th century, however, births started to outpace deaths and between 1750 and 1900 the population rose to 1.7 billion, doubling itself in only 150 years. Population grew at 1% a year from 1900 to 1950, after which the annual growth rate was 2%, representing a doubling of population every 35 years.(2)(3) Until mid-century, the rate of population growth was approximately the same in all regions of the world. After that time, while population in industrialized countries grew by less than 1% a year, in the developing countries it rose by almost 3%. By 1990, of the world's 5.3 billion people, 4.1 billion, or 77%, lived in the developing world while 1.2 billion inhabited the industrialized countries.(4) Improved health care and a younger population in the developing countries accounted for this widening population gap. By the year 2000, over 90 million people will be being added annually to the population of the developing countries. As Table 1 shows, by 2025 the developing countries will account for about 84% of the world's population and the discrepancy between them and the industrialized countries will be even more evident, even though it is projected that a decrease in the number of people added each year will result in a stabilization of world population at 11.2 billion in 2100.(5) Such stabilization will largely depend on the success of population planning programs. While these have been relatively successful in rapidly industrializing nations such as Thailand, the Republic of Korea and China, growth rates in Africa, as Table 1 shows, continue to increase.(6) Women's access to contraception and their attitudes to birth control will play an important part in containing population growth.

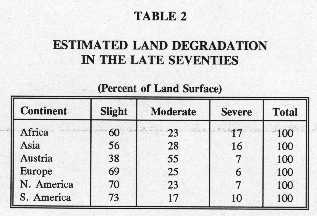

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects 1990 United Nations, New York 1991, p. 226-233, 244-245, 252-255, 264-265, 274-275, and 582-583 as quoted in World Resource Institute, World Resources, 1992-93, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 76. Population control through family planning is central to the concept of sustainable development, which is possible only if human populations are kept in balance with the natural resources that support them. Populations can not be sustained beyond the carrying capacity of the region; if they are not limited by conscious human effort, they are likely to be limited by natural resource constraints.(7) The next sections of the paper explore the balance of food demand and supply with a view to determining the ability of the global village to expand its food capacity sustainably to meet future food needs. Only one third of the population of developing countries live on land that produces enough food to supply its people.(8) The rate of population growth has a lot to do with this equation. The countries and regions with above-average population growth and inadequate agricultural and overall economic growth face a continuing challenge in providing sufficient per capita food supply.(9) Population size and density do not per se cause natural resource degradation or hunger. Such problems arise when the population becomes too large in relation to the productivity of the resource base. Low population areas of the world, such as many regions of Africa, are often areas where the resources cannot support many people. While population is one side of the equation, land productivity is the other. In Africa, for instance, about 80% of the continent cannot be considered cultivable and only 7% of the arable land has productively rich alluvial soil.(10) Historically, a growing population to land ratio has led to intensified production. Technological change and modern inputs (fertilizer, improved seeds, irrigation) more than made up for the unfavourable changes in land to people ratios. As a result, in global terms, the rapid population growth of recent decades was more than matched by commensurate increases in agricultural production. The situation, however, is not so comforting in all countries and regions. Over the last two decades, per capita agricultural production declined in many countries, particularly in Africa, where one African in five is now fed by imported food. This also happened in countries where there was scope for maintaining or increasing the land to people ratios. Inadequate infrastructure and economic incentives have impeded the advent of the technological change that underpinned growth in other countries and regions.(11) Declining food production per capita is one indicator that population growth is outrunning land resources.(12) The fundamental problem in feeding the world's population is not inadequate capacity for production, but unequal distribution of that capacity in relation to population. No absolute food shortage on a global basis exists now or is projected in the foreseeable future.(13) Global grain production is currently more than enough to provide every man, woman and child in the world with a daily ration of 3,000 calories and 65 grams of protein. Yet hunger is an obvious reality in our present world. An increase in world food production would not solve the problem of distribution, and, by itself, would not reduce the incidence of hunger.(14) The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has predicted that world demand for food could increase by 50% during the next two decades and will at least double between now and the year 2050.(15) By the end of the century, that organization projects that one person in six in the developing world (excluding China) will be forced to exist on a diet inadequate for supporting a normal life. The countries of South Asia and Africa will continue to be the most adversely affected.(16) FOOD SUPPLY AND THE DIMINISHING RESOURCE BASE None of the basic resources required to expand food production - land, water, energy, and fertilizer - can now be considered abundant or inexpensive. In developing countries, there has been serious degradation of arable land. Population pressures have caused grave over-exploitation of soils. Irrigation, overgrazing, and denudation of huge forest areas to obtain wood for fuel and to clear land for farming have further reduced the soil's capacity to produce. Some of this land is marginal for farming, with soil and climatic conditions poorly suited for annual cropping.(17) This is especially true where the more fertile lands are already crowded and the population spills over on to marginal land. Such land can only produce low yields and is more or less susceptible to degradation, depending on the quality of management.(18) According to the Worldwatch Institute, an organization which monitors progress towards a sustainable world, soil erosion is slowly undermining the productivity of one third of the world's cropland. Each year, the world's farmers lose an estimated 24 billion tonnes of topsoil in excess of new soil formation.(19) Deforestation is leading to increased rainfall run off and crop-destroying floods.(20) Between 1970 and 1990, the world lost nearly 200 million hectares of tree cover and deserts expanded by some 120 million hectares.(21) The U.S. Department of Agriculture has categorized agricultural land by degree of degradation as shown in Table 2. The extent of degradation in the developing countries even 20 years ago was already apparent. The case of Africa is particularly disturbing, given its growing population pressures. According to the FAO, soil erosion could reduce agricultural production in Africa by one fourth between 1975 and 2000 if conservation measures are not adopted. Lands are farmed ever more intensively as human numbers grow. The shifting cultivation traditionally practised in Africa to maintain soil fertility has begun to break down under high population densities as farmers return to the same plot every five to ten years instead of waiting 20 to 25 years as was customary in the past. As the following cycle shortens and the land's vegetative cover diminishes, soil erosion and land degradation accelerate.(22) Studies show that a loss of one inch of topsoil can, for instance, reduce corn yields by roughly 6%. If the world is losing 24 billion tonnes of topsoil annually (as Worldwatch estimates), it has been estimated that this would mean a grain harvest loss of between 9 and 20 million tonnes per year. Salinity, pollution, and global climate change are also affecting world food production. Worldwatch estimates that these factors add up to an annual loss of 14 million additional tonnes of grain or 1% of output.(23) In terms of these figures, annual food aid of 10 million tonnes worldwide would barely match production losses, let alone provide enough for expanding populations.(24)

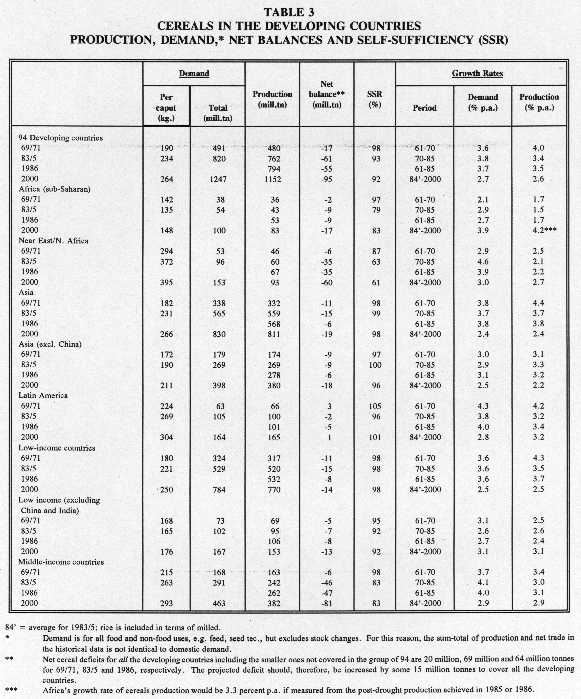

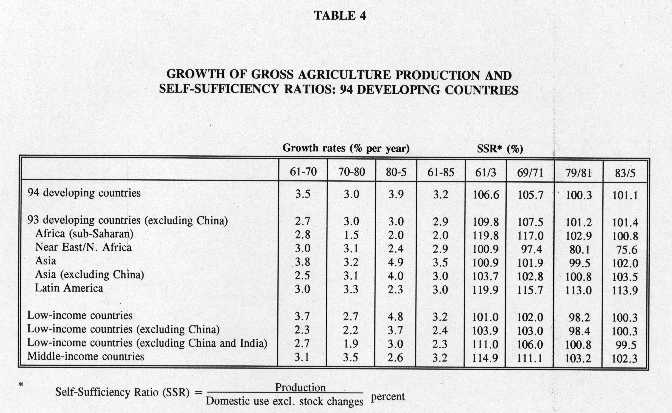

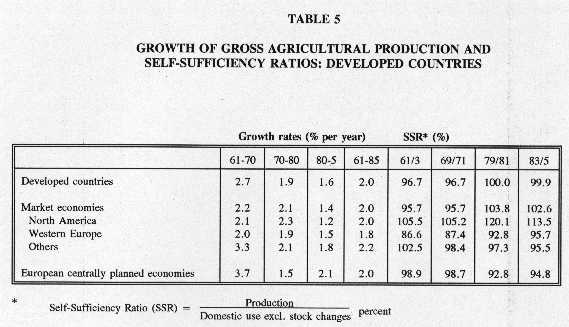

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, World Agriculture Situation and Outlook Report, Washington, D.C., June 1989, based on data compiled by Harold E. Dregne as quoted in Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 1990, Ed. Lester R. Brown et al. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1990, p. 60. The provision of food to the poorer nations will surely remain a major challenge for mankind for many decades.(25) The Macdonald Commission reported two trends in the global food economy in the final quarter of the century. Fewer countries are now able to produce a comfortable margin of excess food; and the world is depending more on North America, particularly the U.S., for its supplies of cereals. Of the few countries still exporting grain, Canada stands high on the list.(26) Food production is a mainstay of our current economy. According to the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Canada's main government body distributing overseas aid, Canadians are the largest per capita food aid donors in the world. Between 1978-79 and 1986-87 Canada provided 7.7 million tonnes of cereals, plus vegetable oil, skim milk powder, pulses and fish.(27) A study(28) published by the FAO in 1979 projected a rate of growth of agricultural production in developing countries of just under 4% in the last quarter of the century. Such an annual rate of growth depended on a 7% increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rate. The 1979 study projected that, unless the 7% growth rate was achieved, demand would outstrip supply, with the net cereal deficit possibly rising to 91 million tonnes in 1990 and 153 million tonnes in 2000.(29) The actual GDP increase was 3.5%.(30) The desired growth rate was not achieved, largely because of the world recession. The deficit projected in 1988 for the year 2000 is, however, about that predicted by the 1979 study for a decade earlier. Lower population and demand forecasts contribute to the revised figure of a deficit of 95 million tonnes by 2000, as evident in Table 3.(31) Food production in developing countries has increased by about 3% a year over the last three decades - more than doubling in volume, and growing about one third faster than in developed countries, as shown in Tables 4 and 5.(32) There has, however, been considerable variation in growth. While countries like India and China have increased production strongly, growth in Sub-Saharan Africa has been weak because of climate setbacks, unsettled political conditions and government policies that have discouraged local food production. Per capita food production has dropped by some 20% over the last 20 years. Population continued to grow annually by 3% while food production growth dropped to only 1.2%. Grain imports absorbed 20% of total foreign exchange earnings.(33) To date technological advances in agriculture have allowed increases in food production to outstrip population growth in many developing countries, thus helping to keep in delicate balance the carrying capacity of the land. This may not continue to be possible, however, unless the global village pursues sustainable directions. The next section looks at some of the constraints that affect the ability of developing countries to become food self-reliant.

Source: Nikos Alexandratos, Editor, World Agriculture Toward 2000, an FAO Study, Belhaven Press, London, 1988 p. 87.

Source: Nikos Alexandratos, Editor, World Agriculture Toward 2000, an FAO Study, Belhaven Press, London, 1988, p. 33.

Source: Nikos Alexandratos, Editor, World Agriculture Toward 2000, an FAO Study, Belhaven Press, London, 1988, p. 38. THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER The approximately 880 million Third World citizens who live in absolute poverty are primarily rural people, overwhelmingly dependent on agriculture to eke out a marginal existence.(34) That food producers are among the most undernourished of the world is a particular irony but findings confirm that, even with current levels of farming technology and full use of all existing arable land, 50% of developing countries lack the land resources needed to meet their people's food needs in the year 2000.(35) While the proportion of the world's people living in these conditions has diminished over the past generation, their number has actually grown. The House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade has called this the "single greatest failure of development."(36) The mushrooming of population in many developing countries is putting additional stress on a global environment already reeling under the blows of rapid and careless economic growth in many parts of the world. Environmental recovery thus depends on meeting the needs of the poorest people and countries. Since most of the people of these countries derive their livelihood and incomes from agriculture, it is agricultural development that needs to address the basic source of poverty and low standards of living.(37) Within the overriding objective of increasing aggregate agricultural output in Third World countries, a primary goal must be to improve the welfare of rural families through enhancing the productivity of small farms and promoting access to resources, markets, and technical assistance.(38) The role of smallholders has tended to be underplayed in agricultural development assistance. It has been estimated that only 15% of production increases in developing countries will result from expansion of the existing cropland base; thus improved technology is expected to have a vital role in increasing production.(39) India is often given as an example of successful technology transfer; over a period of 20 years, that country has become a cereal exporter through the adoption of technological developments such as high yield varieties of wheat and rice. Unfortunately, high yielding varieties fulfil their potential only when cultivated in conjunction with irrigation, pesticides, herbicides, and top-grade land. If any of these factors is missing, the modern variety generally performs more poorly than those it displaced. As well, genetic diversity is eroded when a single variety replaces the hundreds of locally adapted varieties. Monocultures of genetically uniform plants are also extremely susceptible to disease epidemics, while genetic diversity helps plants withstand pests and enables them to tolerate climatic fluctuations. Traditional farmers use diversity to forestall calamity in the face of climatic or market risk. Cultivating crops that exhibit different properties and thrive under different conditions reduces risk. For the vast majority of farmers around the world, reducing risks is far more important than maximizing productivity. The question remains why acceptance of indigenous traditional strains is not more widespread. Part of the problem is that some perceive traditional crops as backward, and anti-development.(40) As well, government policies may work against relying on indigenous solutions; for instance, credit may be available only for high-yield packages, and traditional varieties may not be sanctioned. Land tenure may also be a consideration. Preserving the land by less use of inputs and more use of traditional varieties may not be a goal of either landlord or tenant.(41) The record for the successful introduction of advanced technologies in the Third World is very poor, especially in Africa. The Green Revolution, so successful in parts of Asia, did not transplant well to Africa with its fragile soils, variable climates, and need for irrigation. African governments inaugurated a range of projects in the 1970s aimed at increasing domestic food production. Their mainly Western donors favoured large, mechanized, and highly capitalized projects and crops like wheat, rice, and sugar that were preferred by urban consumers.(42) Western countries during this period poured $22.5 billion in economic development aid into sub-Saharan Africa. Yet by 1986, this region required 9.6 million tonnes of food aid a year. The reason is that only 12% of the aid reached rural areas, and even less got to smallholders, who are thought to be Africa's most productive farmers.(43) In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on the development of small-farm agriculture but there remains the problem of limited adoption of introduced technologies, termed the "technology applications gap."(44) Agriculture is shaped by the interaction of three basic factors: technology and resources; the regional social, economic and political environment; and the socio-organization of the farm.(45) In technology transfer to small farms, an understanding of the third factor is critical to the viability of the "improved" technology. Many new technologies are simply inappropriate because those developing and transferring them have an inadequate understanding of the socio-economic organization and goals of small-farm systems.(46) The FAO predicts that any fundamental technological breakthroughs will encounter the typical 10- to 15-year lag between scientific accomplishment and widespread use at the farm level.(47) This is a problem not only in the development context. A recent study found that there is generally insufficient dialogue between scientists and farmers on technological solutions.(48) Scientists may be expert on the array of solutions to agricultural problems and constraints and in testing technologies within specific environments. Farm families are knowledgeable about their physical, economic, and social environment and their farming system. They know the goals they are trying to meet, the resources and factors of production available, and the critical constraints and pressure points affecting production. Uniting the two knowledge systems is not an easy task and the mechanisms for integrating the small farmer into the process of technology design are still experimental. However, if technology transfer is accepted as a complex process of socio-economic change, then there is no real alternative to it.(49) The integration process has been found to involve four distinct steps: learning about the client; integrating the farming circumstances into the project process; involving the farm family; and evaluating the adoption of the technology.(50) Ideally, all four steps should take place in technology transfer; however, any one would enhance the integration of the small-farm family. Such an approach ensures defining any problems correctly, collecting all the information needed and designing a useful response. Integrating the perspectives of farmers and their knowledge at an early stage in the technology design process also helps clarify research and technological priorities. Designing new technologies in isolation from the farming systems to which they will be introduced often results in an application that is inappropriate for farmers' needs. Case studies demonstrate, for instance, that the success of development projects can be undermined by failure to recognize the different sexual division of labour in farming for cash and farming for food crops. If men are targeted for assistance and women do all the work, the latter have little incentive to increase output.(51) In other words, "small-farm producers tend to evaluate any introduced technology in terms of its compatibility with the goals of the household and the constraints and opportunities confronting the integrated household system."(52) An important related issue is training people to adapt, innovate and invent new technologies appropriate to their own needs and societies. Successful adaptation involves installing technology slowly, in stages, while maintaining a continuing link between the introduced technology and the local community; for example the local area might provide some resource, or the process might make use of some local knowledge.(53) Emissions, effluents, soil erosion and destruction of rain forests all point to the power of outdated western technologies to wreak havoc in the south. This does not imply that the developing world needs more sophisticated western technology. Informed observers emphasize that the devices best placed to bring the most spectacular gains, especially in resource conservation and reduction of pollution, are decidedly low technology, and often pay for themselves within a year or two.(54) Technology transfer is consequently not a one-way street. As Third World governments and tribal communities realize the potential of their traditional knowledge, this will become a potent commodity in technology transfer.(55) The development of products and processes tailor-made for local conditions, and the exchange of ideas between countries at similar stages of development, may turn out to be a more promising model than blindly importing alien western technologies. Looked at in this way, indigenous knowledge is at least as valuable to Third World countries as western scientific skills. The trick is to marry the two.(56) HOW DO DEVELOPED COUNTRIES RESPOND? While prospects for improvement require the governments of Third World countries to revise their policies and accord higher priority to agricultural development, progress also depends on the willingness of the governments of developed countries to increase their technical and financial assistance to Third World nations.(57) In 1987-1988, Canada's Official Development Assistance (ODA) amounted to $2.7 billion, representing about 0.5% of GNP or about 2% of federal government spending.(58) The goal is to achieve 0.7% of GNP by the year 2000. In 1984, when the plight of millions threatened with starvation in Africa came to international attention, Canada responded generously. Canadians recognize that the alleviation of mass hunger and poverty in less developed nations is a critical aspect of our international relations. There was also consensus that development in Africa is a long-term problem which cannot be alleviated solely by short-term crisis aid.(59) Aid can no longer be viewed as a temporary ad hoc measure supporting a simple model of development leading to industrial takeoff. The preceding section has emphasized that development is not just a matter of transferring goods or technology; questions of equity and participation must also be addressed. The poor must become agents of their own development.(60) Aid is at best one supporting aspect of development and cannot become a substitute for appropriate domestic and international policies.(61) Until recently, it has been characteristic of developing countries to accord higher priority to industrial development and related infrastructure than to the agricultural sector. Since the food crisis of the early '70s, a number of developing countries have become aware that too slow a growth in the agricultural sector holds back overall economic growth and intensifies existing and serious social problems.(62) Although by the 1970s donor nations were adopting basic human needs approaches to development assistance, a decade later as much as 30% of bilateral aid still went to upper middle-income countries. Aid has been least effective where it is needed most - the poorest countries and people, particularly in Africa.(63) Like many developed countries, Canada, in trying to run a multi-purpose program, has fallen short in the sector most likely to help the rural farm families who are amongst the poorest of the world's people. As Table 6 shows, about 13% of CIDA's bilateral aid went to agricultural development and a comparable amount went to food aid.(64) Food aid has customarily been considered as a major policy instrument. In recent years Canada has provided well over $300 million of food aid annually through the World Food Program, bilateral assistance and Canadian non-governmental organizations. Food aid has sometimes been accused of being a surplus disposal scheme that can act as a disincentive to agricultural production in developing countries. CIDA, however, sees it as supporting the gradual build-up of local production and as responding to the humanitarian and balance-of-payments problems of developing countries.(65) Canada also supplies technical personnel; technical assistance comes second only to education in personnel numbers. While Canada's support for these activities has increased substantially in the past few years, there is still room for more emphasis on human-scale resource development that encourages the recipients to become more self reliant, even if it inevitably brings them into competition with donor countries.

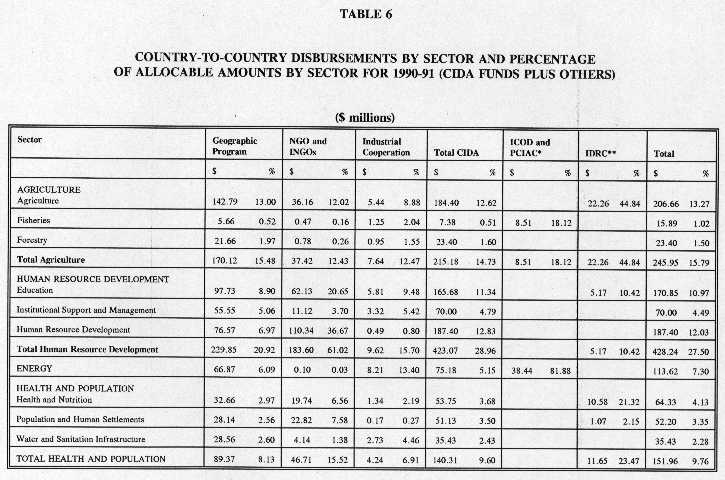

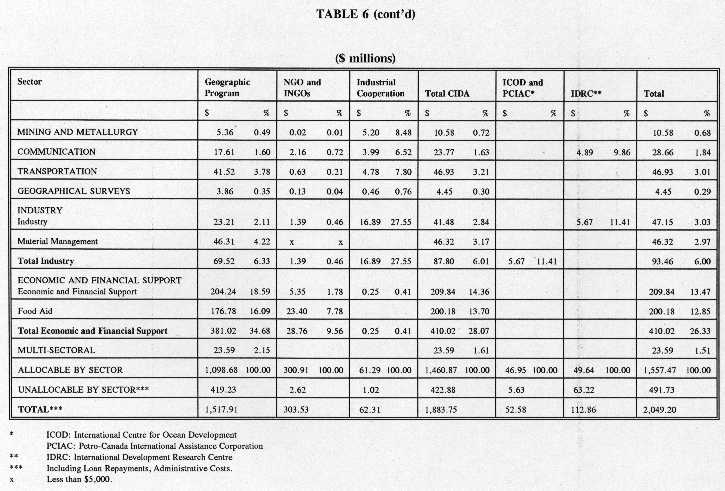

Source: CIDA Annual Report, 1990-91, p. s55-s56. Agricultural development presents a complex area for aid activities, however well-intentioned. The discussion above on technology transfer shows the importance of an understanding of the socio-economic environment in which farming operates. Other key components of successful aid programs relate to domestic policy approaches towards both agriculture and other sector support of agricultural goals. Developing countries' lack of institutional structures and trained personnel can hamper aid to agricultural development. The need for effective village-level organization for enlisting the participation of producers, especially small farmers, in development activities has already been mentioned.(66) In the long-run, well designed aid programs not only have the potential to "kick-start" the process of self-reliance in developing countries but will provide countries like Canada -which depend so much on export growth for their survival - with new markets for their products. Experience has shown that as the agriculture sector is strengthened, and incomes thereby improved, consumer expenditures on food increase sharply, resulting in substantially greater demand for food than the increases in domestic production can accommodate. AGRICULTURE AS THE BELLWETHER MEASURE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH There are weighty reasons for emphasizing the acceleration of food production in developing countries, most of which cannot afford and do not wish to depend on rapidly increasing imports of food from developed countries. Farming generally looms so large in their economies that national income can grow satisfactorily only with good agriculture performance. Distribution improvements are said to be easier to make when production is rising strongly rather than stagnating.(67) The traditional method of measuring human progress and assessing future prospects has been to use income-based GNP (Gross National Income) and GDP (Gross Domestic Product) performance. Ever since national accounting systems were adopted a half-century ago, per capita income has been the most widely used measure of economic progress. The aim of national accounting is to provide an information framework suitable for analyzing the performance of a country's economic system.(68) In the early stages of economic development, expanded output translated rather directly into rising living standards. It became customary to equate progress with economic growth. Over time, however, average income has become less satisfactory as a measure of well-being. It does not reflect how additional wealth is distributed or the environmental debt the world is incurring as the earth's natural capital is depleted.(69)

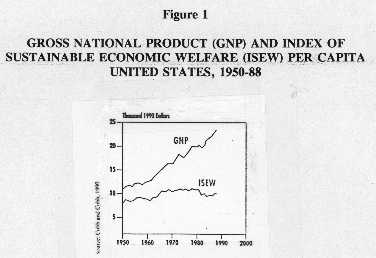

With a few exceptions, only goods and services exchanged in the market economy are included in national income accounts, since market prices offer a means of establishing value. While depreciation of capital assets is subtracted from GDP, depletion of such national assets as forests do not show up as a capital consumption or account debit. Since the basis of accounting is to measure differences in the accounts in terms of time intervals, such an omission is not logical. "Improving" land is included as a contribution to recorded income, though, in fact, it may eventually destroy the income potential through over-exploitation. As Repetto says, "The national accounts thereby create an illusion of development, when, in fact, national wealth is being destroyed. Thus, economic disaster masquerades as progress."(71) Natural resources, such as the land on which agriculture depends, are an economic asset and not a free gift of nature as their treatment in the national accounts would suggest. Even though the World Bank, in its 1991 Report, equated sustainable economic development with better living standards in the areas of education, health and environmental protection, it continues to use economic development formulas that discourage investment in people, health and education. GNP, GDP, inflation, interest, unemployment and other economic indicators tend to foster a view that equates real wealth with mere money.(72) Slowly a recognition is growing that we must find new ways to measure progress. Two interesting recent developments are the Human Development Index (HDI), devised by the United Nations, and the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), presented by H. Daly and J. Cobb in their book For the Common Good.(73) The HDI uses longevity, knowledge and command over resources as indicators of a good life. Statistics include life expectancy, literacy, and GDP adjusted by purchasing power. A high average life expectancy, for instance, indicates broad access to health care and adequate supplies of food. The United States, which leads the world in adjusted per capita GDP, ranks nineteenth according to the HDI measure, below such countries as Australia, Canada and Spain.(74) The HDI takes into account real purchasing power rather than money income alone.(75) According to Lester Brown of Worldwatch, while the HDI is a more satisfactory measure of human well-being, it does not reveal environmental degradation. The ISEW, however, takes into account depletion of non-renewable resources, loss of farmland from soil erosion and urbanization, loss of wetlands, and the cost of air and water pollution. At present this index has been calculated only for the U.S., where it shows a rise in sustainable economic welfare per person of some 42% between 1950 and 1976 but a subsequent fall of 12% from that level by 1988 (see Figure 1).

Source: Ecodecision, June 1992, p. 22. Costa Rica appears to be one of the first developing countries to incorporate depreciation of natural resources into national income accounting. As in many other developing countries, Costa Rica'a natural resources are its most important economic asset yet they have been seriously degraded. Cattle pasture has spread over 35% of the land although only 8% is suitable for this use. The majority of the territory is suited only for forests, yet only 40% remains under forest cover.(76) Over 20 years, natural resource assets in that country valued at more than one year's worth of GDP disappeared. This represented a 30% reduction in potential economic growth. In 1984, for example, soil depreciation equalled 9% of the value added in agriculture. Table 7 depicts how the inclusion of natural resource depreciation in the national accounts provides a better indication of the health of a nation's economy. Its inclusion reduced GDP by 9% in 1989.

Source: R. Repetto et al., Accounts Overdue: Natural Resource Depreciation in Costa Rica, Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute, 1991 as quoted in Environment, September 1992, p. 43. If the goal of agriculture worldwide is to meet the current generation's food needs without depriving future generations, then we must be able to measure accurately whether current consumption is depleting a country's productive assets at the expense of the income of future generations.(77) As Repetto puts it:

If we continue to measure human progress by GNP and GDP, we are soon likely to have a rude awakening about our ability to feed the world's poor children. The first step is to find out whether various regions across the world are producing food within the carrying capacity of their national resource base. The next step is to put in place policies for sustainable development of our food resources so as to make possible the nourishment of future generations. Alexandratos, Nikos, Editor. World Agriculture: Toward 2000, an FAO Study. Belhaven Press, London, 1988. Brown, Lester B. "Economics versus Ecology: Two Contrasting Views of the World." Ecodecision, June 1992. Canada, Parliament, Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade. First Report to the House. For Whose Benefit? Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, Issue No. 26, 20 May 1987. Henderson, Hazel. "New Indicators for a Changing World." Ecodecision, June 1992. Repetto, Robert. "Earth in the Balance Sheet: Incorporating Natural Resources in National Income Accounts." Environment, September 1992. Sands, Deborah M. The Technology Applications Gap: Overcoming Constraints to Small-Farm Development. FAO Research and Technology Paper 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 1986. World Bank. World Development Report 1992, Development and the Environment. Oxford University Press, New York, 1992. World Resource Institute. World Resources, 1992-93. Oxford University Press, New York, 1992. Worldwatch Institute. State of the World 1990. Ed. Lester R. Brown et al. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1990.

(1) Royal Society of London and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Population Growth, Resource Consumption and a Sustainable World, A Joint Statement, Spring 1982, p. 4. (2) North-South Institute, "World Population: Continuing Challenges," Briefing, No. 11, Ottawa, Ontario, 1985, p. 2. (3) Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, (the Macdonald Commission), Volume One, Supply and Services, Ottawa, August, 1985, p. 80. (4) World Resource Institute, World Resources, 1992-93, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 76. (5) Ibid. (6) Ibid. (7) James W. Kirchner et al., "Carrying Capacity, Population Growth, and Sustainable Development," Rapid Population Growth and Human Carrying Capacity: Two Perspectives, Dennis J. Mahar, Editor, World Bank Staff Working Papers, Number 690, The World Bank, Washington, 1985, p. 85. (8) The Macdonald Commission (1985), p. 84. (9) Nikos Alexandratos, Editor, World Agriculture: Toward 2000, an FAO Study, Belhaven Press, London, 1988, p. 72-74. (10) Kirchner (1985) p. 59-60. (11) Alexandratos (1988), p. 72-74. (12) Ibid. (13) The Macdonald Commission (1985), p. 84. (14) Paul Sauvé, "Agriculture's World Challenge," Canadian Banker, No. 93, August, 1986, p. 6-13. (15) Ibid. (16) The Macdonald Commission (1985), p. 85. (17) World Bank, World Development Report 1992, Development and the Environment, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 27. (18) Kirchner (1985), p. 61. (19) Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 1990, Eds. Lester R. Brown et al., W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1990, p. 60. (20) Ibid. (21) Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 1991, Eds. Lester R. Brown et al., W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1991, p. 3. (22) Worldwatch Institute (1990), p. 60-61. (23) Ibid., p. 61-64. (24) Canada, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Sharing Our Future, Minister of Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa, 1987, p. 55. (25) Ibid., p. 89. (26) The Macdonald Commission (1985) p. 86. (27) CIDA (1987), p. 55. (28) Food and Agriculture, Agriculture Toward 2000, A Unipub Reprint, Rome, July 1979. (29) FAO (1979), p. 182. (30) Alexandratos (1988), p. 1. (31) Ibid., p. 85. (32) Ibid., p. 32, 36. (33) M. Waring, If Women Counted, Harper and Row, New York, 1988, p. 179. (34) Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, First Report to the House, For Whose Benefit? Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, Issue No. 26, 20 May 1987, p. 9. (35) The Macdonald Commission (1985), p. 85. (36) Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence (1987), p. 9. (37) Canada, Canadian International Development Agency, Canadian Assistance to Third World Countries in Food and Agriculture, Briefing Notes for the House of Commons Committee on Agriculture, undated. (38) Deborah M. Sands, The Technology Applications Gap: Overcoming Constraints to Small-Farm Development, FAO Research and Technology Paper 1, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 1986, p. 1. (39) The Macdonald Commission (1985), p. 85. (40) Jeremy Cherfas, "Farming Goes Back to its Roots," New Scientist, 9 May 1992, p. 13. (41) Ibid., p. 13. (42) Jack Sheppard, "When Foreign Aid Fails," The Atlantic Monthly, April 1985, No. 255, p. 42. (43) Ibid., p. 43. (44) Sands (1986), p. 1, 65. (45) Ibid., p. 2. (46) Ibid. (47) Alexandratos (1988), p. 12. (48) Canada, Parliament, The Path to Sustainable Agriculture, Report of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture, May 1992, p. 28. (49) Sands (1986), p. 65. (50) Ibid. (51) Ibid., p. 12-13, 75. (52) Ibid., p. 3. (53) Fred Pearce, "The Hidden Cost of Technology Transfer," New Scientist, 9 May 1992, p. 38. (54) Ibid. p. 37. (55) Ibid., p. 39. (56) Ibid. (57) Canada, Canadian International Development Agency, Agriculture in Third World Countries, Hull, May 1984, p. 2. (58) Canada, Canadian International Development Agency, Canadian International Development Assistance, To Benefit a Better World, Response of the Government of Canada to the Report by the Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Minister of Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa, 1987, p. 9. (59) Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Discussion Paper on Issues in Canada's Official Development Assistance Policies and Programs, July, 1986, p. 1. (60) Ibid., p. 4. (61) Ibid., p. 2. (62) FAO (1979), p. 6. (63) House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Discussion Paper (1986), p. 5. (64) Canada, Canadian International Development Agency, Annual Report 1990-91, Minister of Supply and Services Canada, April 1992, p. S55-56. (65) CIDA (1987), p. 54. (66) CIDA (Briefing Notes, undated), p. 2. (67) FAO (1979), p. 6. (68) Robert Repetto, "Earth in the Balance Sheet, Incorporating Natural Resources in National Income Accounts," Environment, September 1992, p. 13. (69) Lester B. Brown, "Economics versus Ecology: Two Contrasting Views of the World," Ecodecision, June 1992, p. 19-21. (70) Repetto (1992), p. 14. (71) Ibid., p. 15. (72) Hazel Henderson, "New Indicators for a Changing World," Ecodecision, June 1992, p. 60. (73) H. Daly and J. Cobb, For the Common Good, Beacon Press, Boston, 1989. (74) Lester R. Brown, "Economics Versus Ecology: Two Contrasting Views of the World," Ecodecision, June 1992, p. 21. (75) Henderson (1992), p. 60. (76) Repetto (1992), p. 17. (77) Ibid., p. 43. (78) Ibid., p. 44. |