|

BP-322E

THE LAW OF THE SEA CONVENTION

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS C. Relationship to Other International Law D. Fundamental Principles of the LOSC F. Present Status of the Agreement A. Territorial Division of the Sea, Sea-Bed and Subsea 7. Special Cases of Interest to Canada B. Boundary Delimitation between Adjacent States b. The St. Pierre and Miquelon Dispute C. State Jurisdiction aboard Ships at Sea EXPLOITATION OF MARINE RESOURCES A. Fishing Rights and Obligations 1. General Conservation and Sharing Obligations 2. Rights within the TS and EEZ B. Non-Living Sea-Bed Resources CONSERVATION OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT 2. Monitoring Pollution and Risks B. Transit and Navigation Routes A. Obligations regarding Resolution B. Conciliation and Binding Arbitration 1. International Tribunal for the LOS

THE LAW OF THE SEA CONVENTION

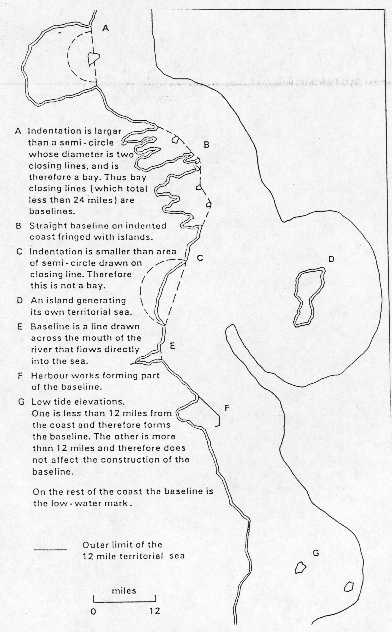

The 1982 Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) is an enormously complex international treaty which deals with many of the major issues of our time - State sovereignty, resource development, international commerce, environmental protection and military activities. This treaty, which is likely to come into force soon, will be the principal governing body of law over an area three times as large as all the continents put together. Canada is an important maritime nation. It has the world's longest coastline, one of the largest claims to territorial jurisdiction on the seas, and several regional economies intimately tied to the ocean. Thus, the LOSC is vitally important for the economic, political and environmental well-being of this country. This paper provides a general overview of the LOSC, particularly in the Canadian context. A single paper cannot hope to discuss all the areas touched upon in the Agreement, so the emphasis has been on those areas of particular importance to Canada: Canadian territorial and shipping jurisdiction on the seas, past and future Canadian maritime territorial disputes, fishing rights and petroleum exploitation, and State responsibility for environmental protection. Three-quarters of the earth's surface is ocean. These vast waters have been a means of international travel and a major communal source of food for millennia. As a consequence, societies developed norms for international behaviour on the ocean long before norms for international behaviour on land.(1) Recent technological changes and growing populations have created new uses and exerted new pressures on the world's ocean resources. The law of the sea, therefore, is an old body of law in a period of rapid evolution. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC or the "Agreement")(2) bridges the gap between centuries-old rights and obligations and the new awareness that the seas are not an inexhaustible resource for those whose geography or economic development facilitates maritime exploitation. The LOSC represents an exceptionally important contribution to international relations, especially for Canada, which has the world's longest coastline and borders on three of the world's oceans. This paper reviews many important aspects of the LOSC, including those elements that also belong to the more general law of the sea. United Nations conferences were held in 1958 (UNCLOS I) and 1960 (UNCLOS II) in order to codify various aspects of the law of the sea. The 1958 Geneva conference led to separate international treaties pertaining to the Territorial Sea, the Contiguous Zone, the High Seas, the Continental Shelf and the conservation of living resources in the sea.(3) As the titles indicate, the primary concern at that time was the territorial division of the seas in response to some very broad and disparate claims to sovereignty by many countries in the post-World War II years. UNCLOS II failed to resolve any outstanding concerns. During the late 1960s through the early 1980s, there were negotiations toward further development of the law of the sea. At first, discussions were limited to the deep sea-bed, but eventually the newly-emergent States reached agreement on a wide array of substantive issues raised by historical and modern use of the sea. In December 1982, a third U.N. conference (UNCLOS III) was convened and the LOSC was signed by 119 States, although many European nations abstained. This wide acceptance signifies the importance of the subject matter and the success of the negotiations in finding the common ground. Although the LOSC contains an almost verbatim restatement of many of the 1958 Geneva Conventions, it is much more wide-ranging, and includes provisions covering developments not yet technologically feasible, but anticipated within the next few decades. The wide support for the LOSC was achieved without having to water the Agreement down so that it said nothing of substance. The LOSC, simply put, is the most comprehensive international treaty ever signed. It ranks along with the Charter of the United Nations (the Charter) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the Universal Declaration) as one of this century's great accomplishments in international cooperation. It is, perhaps, even more remarkable than those basic U.N. documents. The Charter and the Universal Declaration were initially agreed to by just a few dozen western, developed nations who shared common values and concerns; they were agreed to by the newly emerging countries only following decolonization. The LOSC, however, was an agreement of great import and complexity negotiated by an enormous number of States of greatly varying economic status, political outlook and interests. C. Relationship to Other International Law Although the LOSC is a very comprehensive treaty, and one which codifies much of the accepted international law on the subject as it existed in 1982, it is not the only source of the international law of the sea. Customary international law,(4) developed by State practice rather than treaties, remains an important source. Consistently applied customs may be important in local areas where practices have historically deviated from international norms as defined by treaties. As well, a significant body of customary and treaty law outside the LOSC pertains to the law of warfare, pollution control, and general security matters and may become applicable in a marine setting. With respect to boundary delimitation, there is substantial caselaw, which, although not binding on any later tribunal, is persuasive; some basic elements of this must be considered customary law. Finally, the law pertaining to the resource-rich waters below 60 degrees South surrounding Antarctica is influenced by the recently reaffirmed Antarctic Treaty.(5) D. Fundamental Principles of the LOSC Three fundamental principles pervade the LOSC. The first principle is that States have some sovereign rights to some portion of the sea adjacent to their sea coastline. The second principle limits the first; it says that some portion of the sea, the seafloor and the sea-bed are shared as part of the "common heritage of mankind." The final principle is that concomitant with States' rights are States' obligations to preserve the seas and accommodate the needs of other States. The LOSC Agreement is divided into numerous Parts and Annexes which approach the issues of international relations on the oceans from several perspectives. The Agreement divides roughly in half. The first eleven Parts deal with spatial issues, and tend to reiterate long-standing concerns with respect to the seas. The latter Parts deal with functional issues of use and cooperation and more directly address recent concerns. Parts II through VI define the extent and nature of coastal States'(6) proprietary interest in the seas. Parts VII and XI deal with the commonly held areas of the sea and the seafloor, including the economic rights of all States within these areas. Part XII, on the other hand, outlines States' responsibility for protecting the marine environment. Parts XIII and XIV relate to scientific research on the seas, including transfer of technologies to the developing world. Part XV presents mechanisms for resolving disputes. Other Parts and the Annexes deal with specific problems, institutional structures, details of dispute resolution and the operation of the Agreement itself. F. Present Status of the Agreement The LOSC provides that it will not enter into force until 12 months after the 60th ratification. States that have ratified the Agreement are known as "State Parties." Canada has signed but has not ratified the LOSC. As of January 1993, there had been 54 ratifications, few of which were by major industrialized nations or major maritime powers, many of which oppose the deep sea-bed regime. Despite this, there are four arguments for applying the principles in the LOSC, if not the convention itself, to international relations on the seas. First, many States are already bound by the various Geneva Conventions, described earlier, which constitute a significant portion of the first section of the LOSC. Second, the LOSC is a codification of a substantial amount of binding(7) customary international law of the sea as it existed in 1982. Third, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has held that extensive State practice indicates that the LOSC's major new concept of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), if not the specific details, has become customary international law. Finally, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which is itself customary international law, says that States that have signed but not yet ratified a treaty must refrain from acts that would defeat the object and purpose of the treaty. A. Territorial Division of the Sea, Sea-Bed and Subsea The most basic question in the law of the sea is: what constitutes a sea? The international legal definition is not the same as that of an oceanographer. Under the LOSC, the sea is defined as being seaward of a "baseline." The rules for drawing baselines are necessarily complex, since they deal with infinitely variable geography; essentially, however, the baseline is the low-tide line. Special rules for bays, river deltas, estuaries, fjords, reefs, fringing islands, small rocks, etc. project a straight baseline across an open area of water.(8) Straight baselines must follow the general trend of the coast, but there is no steadfast limit as to their permissible length.(9) The longer the baseline, however, the greater the maritime area that is removed from effective use by all nations and, as a result, long straight baseline projections are vigorously opposed by many States. All outward measurements of distance that delineate territorial subdivisions of the sea start from the baseline,(10) as do many measurements used in defining a contested boundary between adjacent States. A coastal State's rights in territorial zones in the sea are progressively attenuated as one moves further away from the shoreline. Internal Waters (IW) are all waters on the landward side of a baseline. They are the legal equivalent of the State's land in international law, except that in very limited instances foreign nations may retain a historical right of passage. Domestic laws will usually apply through a State's IW. Shipping ports are within IW but the LOSC does not provide for a general right to enter for ships in distress, although such a right may exist in customary international law. FIGURE 1

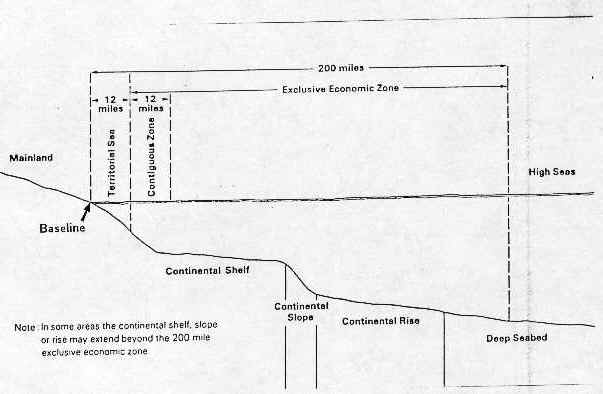

Source: Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 2nd ed., Manchester University Press, Manchester U.K., 1988. FIGURE 2

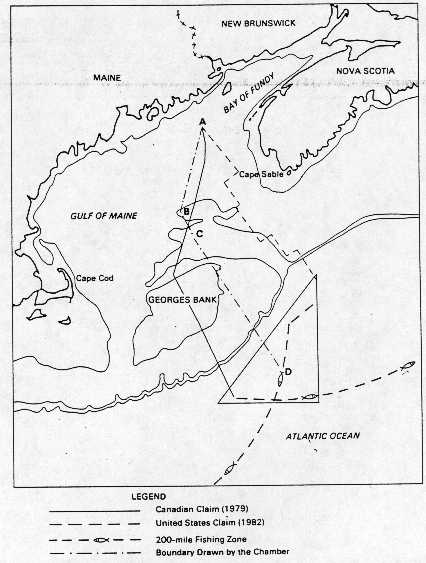

Source: Modified from Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 2nd ed., Manchester University Press, Manchester, U.K., 1988. Depending upon the straight baselines drawn, very large portions of the waters around Canada, particularly within the Arctic, may become part of the IW of Canada. For instance, the government of Canada draws a straight baseline from Resolution Island (just south-east of Baffin Island) 38 nautical miles(11) (herein referred to simply as "miles") south to Cape Chidley, the northernmost tip of Labrador. This straight baseline, if it receives international acceptance, will enclose an enormous body of water, including all of Ungava Bay, Hudson Strait, the Foxe Basin and Hudson Bay. The Territorial Sea (TS) is a band of sea immediately adjacent to the baseline. In the absence of any impinging State, a coastal State may claim a TS of width up to 12 miles. There is no minimum TS that a State must claim. Most States, including Canada, have claimed the maximum permissible. Islands, islets and rocks which are naturally occurring but not capable of sustaining life all generate a TS, provided they protrude above sea level at high tide. Within the TS, the coastal State has the same sovereign rights as on land, except that the ships of all States have the right of innocent passage through the TS.(12) Innocent passage encompasses transit only and the coastal State may set up sealanes in which ships in innocent passage must remain. Activities such as fishing, research, weapons use, loading or unloading of commodities or any threat to the stability of the coastal State are a breach of the right of innocent passage. If such activities take place, the coastal State is entitled to move to prevent further passage or presence within the TS. Warships, although not specifically provided for in the LOSC, probably have a right of innocent passage, for the LOSC allows innocent passage by nuclear ships and submarines. The coastal State also has the duty to publicize navigational dangers within its TS; this may entail an obligation to maintain lighthouses or other warning devices. The Contiguous Zone (CZ) is a band of sea up to 12 miles wide, immediately seaward of the outer margin of the TS; it may be claimed by the coastal State for the purpose of enforcing its domestic laws relating to customs, immigration, fishing and sanitation. Although the coastal State cannot regulate within the CZ, within that zone it can enforce breaches of its laws that occurred on its territory or within the TS. This transitional zone prevents ships from breaking the law and then hovering offshore just out of reach. With the creation of the Exclusive Economic Zone (discussed below), most States have abandoned their former reliance on the concept of a CZ. Although the geologic continental shelf is simply the extension of the continent out under the adjacent sea, the legal Continental Shelf (CS) is more complicated. Formerly, international law set the outer margin of the CS as the 200-metre isobath (a contour at 200 metres water depth) or to such depth as technology would admit exploitation of resources. The LOSC has replaced this with very complicated formulas relating to slope of the floor or thickness of the rocks on the seafloor. The LOSC also set a minimum and maximum CS width of 200 and 350 miles, respectively. As an approximation, however, where the geologic continental shelf extends beyond 200 miles, one can still consider the 200-metre isobath as the CS margin, for this is where a rapid change in slope of the seafloor typically occurs. Rocks incapable of sustaining human habitation do not generate a CS. A State's rights on the CS exist even without any express claim being made. Rights to the CS pertain to the sea-bed and the subsea strata, not to the superadjacent water column, although rights within the Exclusive Economic Zone may cover the water column. A coastal State may not exercise full sovereignty over the CS, but it does have the exclusive right to explore and exploit its living and non-living resources, including minerals, oil, and lifeforms like clams that live fixed to the seafloor. Other nations may lay submarine cables and pipelines across a coastal State's CS. In rare cases, such as at Canada's Nose and Tail of the Grand Banks, the CS extends beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone. This gives the coastal State exclusive right to the seafloor resources of the CS, while resources in the superadjacent water column belong to all nations. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is perhaps the greatest immediate advance in international law stemming from the LOSC. An EEZ is an up to 200-mile-wide band that extends seaward from the baseline and may be claimed by the adjacent coastal State. Most States have claimed the maximum permissible. In almost all cases, the TS and the CZ are within the EEZ. Most CSs are less than 200 miles in width, so the waters above them (which include the vast majority of all economically exploitable fish stocks) are also within the EEZ. Rocks incapable of sustaining life do not create an EEZ about them, although they do create a TS. Within the EEZ, the coastal State has two basic rights: one economic, one jurisdictional. Economically, the coastal State has sovereign rights(13) for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving and managing the living and non-living resources of the water column, sea-bed and subsea strata and other activities of economic exploitation. Jurisdictionally, the coastal State has jurisdiction over artificial structures, marine research and marine environmental protection. One could also read this environmental protection right as a duty, as this would be consistent with the title in the relevant provision of the LOSC. In total, these rights are very far from outright sovereignty. Contrary to general opinion, Canada has not claimed an EEZ, but rather a 200-mile Exclusive Fishing Zone (EFZ), although the terms are loosely used almost interchangeably. EFZs have their origin prior to the LOSC, which Canada's EFZ claim predates, but now many States have claimed an EFZ as wide as the permissible EEZ. A claim to an EFZ, when combined with rights to the CS, gives the coastal State all the economic rights to the area (except "other activities," such as energy generation from waves), without taking on any duties beyond those imposed on all States. In return for claiming the lesser right of an EFZ rather than an EEZ, the coastal State gives up jurisdiction over artificial structures and marine research that may be built or undertaken within the area. Freedom of the High Seas (HS) is a very old legal concept; recent changes in the law of the sea amount to a redefinition of the boundaries of the HS without altering State rights within the HS. The HS comprise all those areas of the sea where no jurisdiction is exercised by a coastal State; usually this is all waters seaward of the outer margin of the EEZ of the adjacent coastal State. The HS belong to all mankind. They are characterized by the freedom of all States, land-locked or not, to navigate through, fly over, fish upon, conduct scientific research in, lay cables, build artificial islands, etc., provided these activities are carried out with due regard to the rights of other States and for peaceful purposes. States may not claim jurisdiction over the HS; however, in the limited circumstance of a "hot pursuit," a coastal State that chases into the HS a foreign ship that has transgressed its laws within its EEZ or TS may enforce its laws on the HS. In "hot pursuit," the chase must have begun while the foreign ship was within the pursuing State's waters and continue until the ship is apprehended. The use of necessary force to apprehend a ship is not considered to be a violation of States' obligation to use the HS for peaceful purposes only. It has become popular for many governments and opinion leaders to call for economic sanctions, including enforced trade sanctions, against a State felt to be in violation of international public order. Such actions were recently used against Iraq and Serbia. However, a naval blockade is, prima facie, a violation of freedom of the HS. Such efforts constitute a violation of international law if not conducted with the authorization of the United Nations Security Council pursuant to Chapter VII of the Charter. 7. Special Cases of Interest to Canada Pack-ice, in particular permanent pack-ice, presents a problem in law for it takes on many of the characteristics both of sea (for it permits navigation by submarine) and land (especially for the local indigenous peoples at high latitudes). In the absence of any provision to the contrary in the LOSC, permanent ice-covered areas, at least those floating above ocean water,(14) are likely to be considered seas for the purpose of the LOSC. The LOSC grants the coastal State in ice-covered areas a right to legislate throughout the EEZ for the purpose of protecting the fragile environment from pollution damage. Elsewhere in EEZs, States have an economic right but not a legislative right. This brings the LOSC in line with the right asserted by Canada in the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act(15) prior to the LOSC. Straits are narrow channels that connect two larger bodies of water. By their nature they are extremely important to commercial shipping and naval forces. However, straits are usually located in what, but for their status as an international strait, would be the EEZ or the TS of the adjacent coastal State. As there is no set rule of what constitutes a strait, many States will clash over this issue. Canada considers this issue crucial for asserting Canadian sovereignty throughout the Arctic islands, especially with respect to the status of the so-called North-West Passage. The LOSC defines the rights of shipping States within international straits; these rights pertain to transit only, in all other respects a strait retains the legal characteristics of the area in which it resides. Archipelagos are collections of islands in relatively close proximity to one another which have a geographic, historic, economic or political association. The Canadian Arctic Islands and the Greek Islands are examples. Archipelagic States, such as Indonesia, are made up entirely of archipelagos. They receive special treatment under the LOSC, which grants to them jurisdiction over "Archipelagic Waters." Archipelagic Waters resemble a TS and, with some limitations, comprise those waters contained within straight baselines drawn between the outermost islands in the archipelago. The Canadian Arctic Islands, not being a State, do not generate Archipelagic Waters. Although land-locked States do not have a TS or EEZ of their own, the LOSC provided them with many of the rights and privileges of coastal States, including freedom of the HS, a right of innocent passage and the right to share in the wealth of the deep sea-bed. These rights would be hollow if the land-locked State could not gain access to the sea; the LOSC requires coastal States to provide land-locked States with access to the sea by all means of transport. In addition, land-locked States have the right to share equitably in the exploitation of the surplus fishing resources in the EEZs of States within their region. Although the term "region" is not defined within the LOSC, the land-locked States closest to Canada are in Europe and thus not likely to be within many definitions of the Canadian region. Canadians should be aware, however, that despite the name Exclusive Economic Zone, Canada does not, in all instances, have an absolute right to all the fishing resources within the 200-mile Canadian EEZ. B. Boundary Delimitation between Adjacent States Boundary disputes have existed since we began drawing boundaries. However, when the EEZ extended a coastal State's rights out from 12 to 200 miles, it created many new opportunities for dispute, either: (i) where two opposing coasts are more than 24 miles but less than 400 miles apart; or (ii) where adjacent States had agreed to a boundary out for 12 miles, but cannot agree on the further 188 miles. Add to this the newfound petroleum resources of the subsea strata, and one has conditions ripe for boundary disputes. Although delineation of an all-purpose boundary is desirable from the point of view of management, each territorial division of the sea warrants its own uniquely decided boundary. Boundaries close to shore, as between adjacent States or closely-opposing States, tend not to be very contentious; in these cases there usually is plenty of historical evidence to buttress a claim. Further offshore, however, there is more latitude for disagreement. It is primarily in these instances that international law must look to principles rather than history to settle the dispute. The LOSC makes no major new contribution to the law of delimiting marine boundaries between opposing and adjacent States. The Agreement sets out slightly different treatment for TS boundary delimitation from that of the CS or the EEZ. In all cases the LOSC calls on Parties to resolve their boundary disputes by agreement. For the CS and the EEZ there is the additional provision that such an agreement be on the basis of international law and achieve an equitable solution. If no agreement is achieved on a CS or EEZ boundary, the Parties are directed to the LOSC's general dispute resolution procedures.(16) For the TS, the LOSC says only that, in the general case, without an agreement neither State may assert a boundary that is beyond the equidistant point.(17) Since EEZ and CS delimitations are the basis of most boundary disputes, the LOSC simply adopts whatever international law of boundary delimitation exists as its principle for resolving disputes. That principle is exceedingly broad, but it consistently runs through numerous cases on boundary disputes. It can most clearly be stated as: the Parties shall use equitable principles, or equitable criteria, taking into account all the relevant circumstances, in order to come to an equitable result when settling their boundary disputes.(18) Clearly, the result, rather than the means, is the dominant criterion for assessing the suitability of the boundary. Using equitable principles to reach an equitable result does not place great constraints on the actual method employed. This probably is desirable, for it allows for the solution to be effectively tailored in each instance to the particular geography before the tribunal. Equity, by its very definition, will be unique for each new fact situation and, of course, geography is infinitely variable. In situations of very simple geography where there are no "special circumstances," international law seems to have de facto concluded that equidistance should be the principle chosen for boundary delimitation between opposing coasts. The following principles are among the many that have been put forward as equitable principles which should be invoked: sovereign equality between States; political status of the territory; "weight" varying between mainland and islands; equidistance; relative lengths of coastline; non-encroachment(19) of coastal fronts; natural prolongation of land territory; historic use and economic interests; and degrees of frontal overlap.(20) No one principle is equitable in all instances. At various times an equitable result, it has been argued, is one that divides the relevant and disputed marine waters: (i) equally; (ii) in proportion to the lengths of relevant coastline; or (iii) in proportion to the relevant land areas. In light of so many "equitable principles," it is easy to see why these issues are so contentious and why at times there appears to be no discernable trend in tribunal decisions. How equitable principles play out is best seen within the context of concrete examples, which indicate that there is no sure answer to maritime boundary disputes. Everywhere(21) Canada has a maritime boundary with another State, Canada has a boundary dispute or has recently settled one. These boundaries are: in the Gulf of Maine off the southern tip of Nova Scotia; around the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off Newfoundland; in the Beaufort Sea off the north coast of Alaska and the Yukon Territory; in the Davis Strait and associated waters separating the Eastern Arctic from Greenland; in the Strait of Juan de Fuca south of Vancouver Island; and in the Dixon Entrance between the southern tip of the Alaska panhandle and the Queen Charlotte Islands. The Gulf of Maine and St. Pierre disputes have recently been resolved through litigation; these will be described at greater length below. The Beaufort Sea dispute may have enormous economic ramifications because of the oil potential beneath the disputed waters; it too is discussed below. The Davis Strait and Juan de Fuca Strait disputes are relatively minor readjustments to a line and are unlikely to be highly contentious so are not further discussed here; nor is the Dixon Entrance dispute, which has taken on a political impact far exceeding its economic import owing to the nearby presence of a U.S. submarine facility. In the Gulf of Maine, in the area south of Nova Scotia and north of Cape Cod (see Figure 3), Canada and the United States maintained a long-standing boundary dispute. Complex coastal geography, complicated subsea geologic features, oil potential, and very substantial fishing resources combined to make the dispute difficult to resolve. After agreeing on a short boundary close to land, the countries sent their dispute to an ICJ Chamber(22) asking for a single boundary for the CS and the superadjacent waters.(23) Before the Court, Canada argued the equidistance principle. The Americans initially argued natural prolongation of the land, but changed their claim because of an ICJ decision that largely dismissed that principle. The amended U.S. claim involved boundaries normal to the regional coastal trend with discounting for peninsulas and islands. In sum, though, their amended line, based upon new principles, was very close to the old line they had been advancing. FIGURE 3

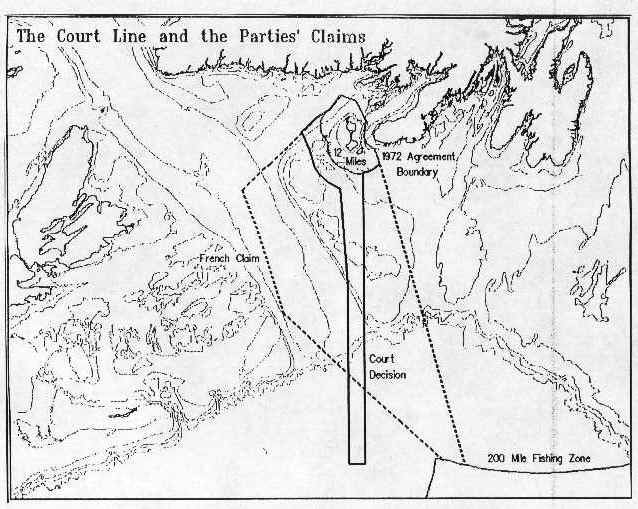

Source: From Kapoor and Kerr, A Guide to Maritime Boundary Delimitation, Carswell, Toronto, 1986. In rejecting both Parties' claims, the Court showed great flexibility. It fashioned a boundary of its own making, which consisted of three segments: an inner section perpendicular to the coast, a middle section roughly equidistant between two opposing coasts, and an outer section facing open ocean drawn perpendicular to an imaginary line joining the two outermost points of land and thereby enclosing the gulf. The decision highlighted the primacy of geographic factors. It was considered equitable because it roughly divided the disputed area into sections proportional to the lengths of relevant coastline. b. The St. Pierre and Miquelon Dispute St. Pierre and Miquelon are two very small French islands south of Newfoundland (see Figure 4). They are 12 miles from Canadian soil but several thousand miles from metropolitan France. In the 1970s, Canada and France agreed to an equidistant boundary on the inshore side between them, but maintained a dispute on the boundary on the seaward side of the islands. The seaward boundary was settled by an arbitration tribunal consisting of eminent jurists from both countries and three neutral countries. Before the tribunal, France argued the equidistance principle. Canada, following a somewhat analogous arbitration decision on the waters around the Channel Islands,(24) argued for enclaving around the islands.(25) In its 10 June 1992 decision, the majority opinion(26) of the tribunal rejected the arguments of both States; however, the decision did contain significant elements of the Canadian enclaving argument even though the tribunal concluded that the Channel Island case was not a relevant precedent. The tribunal decision granted France two areas: an enclave of 24 miles (12 mile TS, 12 mile EEZ) around most of the islands, plus a thin "stem" projecting southward for FIGURE 4

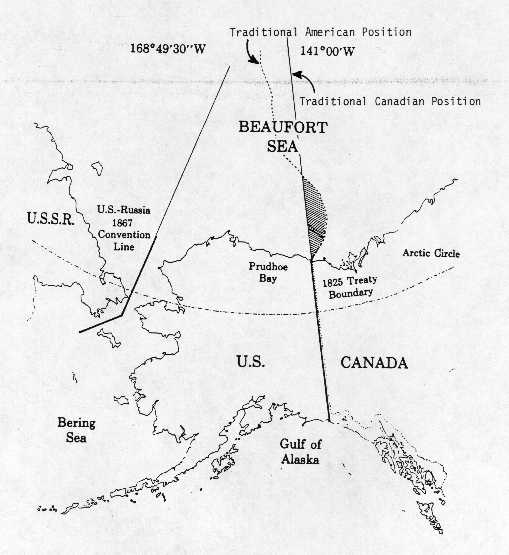

Source: Department of External Affairs press release. 200 miles. The stem projects perpendicular to the general trend of the south coast of the island of Newfoundland. The width of the stem is equal to the width of the islands as measured parallel to the general trend of the south coast of the island of Newfoundland; this minimizes cut off. The tribunal concluded that the area granted to France was equitable, being roughly proportional to the relevant lengths of coastline as determined by the tribunal. Several conclusions which may influence general application were drawn: (i) a territory's maritime rights do not depend on its political status (integral part of the metropolitan State or overseas possession) or geographic status (island or continent); (ii) the Treaty of Versailles (which ceded St. Pierre to France) does not limit France's present maritime rights; (iii) economic dependence upon the fishery does not impact upon boundary delimitation; and (iv) the division of the relevant area should be roughly proportional to the relative coastal lengths. The tone of the decision emphasized equitable rather than legal principles. The land boundary between Alaska and the Yukon Territory is the 141st degree of longitude. How that boundary extends northward on to the Beaufort Sea and the Arctic Ocean is vitally important, for scientific information suggests that the strata beneath the Beaufort Sea have great petroleum potential.(27) There have already been major discoveries of oil and gas further east, in Canadian portions of the Beaufort Sea not under dispute. The respective positions of the two governments are straightforward. Canada contends that the maritime boundary should follow the land boundary along the 141st meridian out 200 miles. At various times, this has been supported by the following arguments: (i) the intent of the 1825 treaty(28) which set the 141st meridian as the land boundary was to include both land and sea; (ii) a similar line divides Russian waters from Alaskan waters; (iii) Canada FIGURE 5

Source: Modified from Rothwell, Maritime Boundaries and Resource Development: Options for the Beaufort Sea, Can. Inst. of Resources Law, 1988. has historically used these waters; (iv) both States have acquiesced in this delimitation; and (v) polar areas are unique, thus the principles of boundary delimitation applied in non-polar regions are not applicable. The United States argument has relied exclusively on equidistance.(29) The implications of an adverse boundary decision in the Beaufort Sea are enormous. As well, petroleum production from the disputed territory is not imminent. Together, these two facts indicate that the two countries are unlikely to go to an adjudicative tribunal for resolution of this dispute. A negotiated solution is likely to be in both countries' best interests. C. State Jurisdiction aboard Ships at Sea State jurisdiction can be roughly divided into two species: legislation and enforcement. In many shipping situations this becomes more complicated, for there are two States involved: the State representing the ship's nationality (flag State) and the State with jurisdiction over the waters in which the ship floats (coastal State). Ships are nationals of the State in which they are registered; or, in maritime jargon, ships are nationals of the nation whose flag they fly. Flag States may exercise legislative jurisdiction over their ships wherever they may be. Usually this entails regulating social, employment, safety and technical matters aboard the ship; the last of which, the LOSC says, must conform to international standards. Concomitant with legislative authority is the flag State's international responsibility for the actions of its ships. Flag States, however, may enforce their jurisdiction only when their ships are within their TS, EEZ or on the HS. To attempt to enforce this jurisdiction within waters belonging to another State would be an infringement of that State's right of sovereignty. Ships passing through waters within the jurisdiction of coastal States provide opportunities for potential conflicts of jurisdiction. For instance, the flag State may set pollution control regulations for its ships, but these may simultaneously come within the purview of the pollution control regulations of the coastal State, when in that State's waters. Although ships at sea have a right of innocent passage within a TS, this passage must be undertaken in accordance with any relevant laws of the coastal State. Coastal States have the legislative jurisdiction to pass laws that apply to foreign ships within their TS pertaining, inter alia, to: safety of navigation, regulation of maritime traffic, sanitation, and protection of cables and pipelines. Enforcement jurisdiction relates primarily to breaches of sanitary laws and is discussed below in the enforcement chapter of the Maritime Pollution section. EXPLOITATION OF MARINE RESOURCES Two significant problems underlie the exploitation of marine resources. First is the tendency to overutilize the communal but finite resources of the HS. The second is the transboundary migration of marine fish resources. The LOSC attempts to regulate both problems. A. Fishing Rights and Obligations 1. General Conservation and Sharing Obligations Prior to the LOSC, international obligations were created to conserve fishing resources,(30) at least for those areas in which there was communal ownership. The LOSC extends these conservation obligations, setting out varying obligations for the TS, EEZ and HS. The Agreement does not mandate conservation of fish stocks within the TS; it says only that the coastal State may adopt laws for fish conservation. However, as the coastal State has sole right to exploit these fish, prudent practices should prevail. Within the EEZ, the coastal State must set an allowable catch, based on scientific information, which is designed to maintain or restore species to levels supporting a maximum sustainable yield (MSY). An MSY need not be entirely scientific, it can also take into account economic factors. For stocks that straddle boundaries between two EEZs or an EEZ and the HS, States must cooperate towards reaching an overall conservation plan. On the HS, States have an obligation to cooperate, consult, negotiate and implement a management plan designed to maintain or restore species to levels supporting a MSY. Note the obligation is to cooperate toward this end, not achieve this end. There are, however, significant loopholes with respect to sedentary species, highly migratory species and andromadous stocks (such as salmon). First, sedentary species,(31) even those located within an EEZ, are exempt from the conservation obligations. Second, though coastal States must conserve highly migratory and andromadous species (which travel through the TS and EEZ on their way to other waters) within its EEZ, there is no similar obligation within the TS. As mentioned previously, the EEZ is a major expansion of coastal States' rights and most of the world's offshore fisheries are located within EEZs. The coastal State, however, has obligations with respect to sharing the excess living resources of the EEZ. Within the EEZ, the coastal State must promote the optimum utilization of fish resources. This term indicates the coastal State's obligation to make available to other countries any surplus fish it lacks the capacity to catch. This surplus must be made available on an equitable basis to other countries, paying particular regard to separate obligations to share the surplus with land-locked States and geographically-disadvantaged States. The coastal State may still regulate the actual taking of the surplus by foreign vessels. The LOSC neither requires nor prohibits a demand of compensation for taking surplus fish. 2. Rights within the TS and EEZ Although fishing rights within the TS and the EEZ are exclusive, in that no other State may fish in these areas without approval of the coastal State, the right of the coastal State to exploit the fishery is not unlimited. For instance, in the TS, where the coastal State has sovereignty as well as an economic right, sovereignty must be exercised subject to the provisions of the LOSC and other international law.(32) The LOSC is clear: although the right to fish may be exclusive, the fish are not "owned" by the coastal State. Rather, the coastal State has a right to fish but the fish remain unowned until caught. In other words, one coastal State, absent a bilateral agreement,(33) has no claim on fish which migrate from its waters into those of another State. B. Non-Living Sea-Bed Resources Geologic structures containing hydrocarbon resources are found both on the continents and under the CS. The oil potential of the subsea strata of the CS is very great, much greater than that of the continental slope and deep sea-bed. Hydrocarbons, whether natural gas, oil or condensate, are all non-living natural resources, which the coastal State has the exclusive right to explore and exploit without the need for any express proclamation. The terminology of "right to explore and exploit" is curious, for it arguably leaves possible the contention that, absent exploitation of these resources, the coastal State does not yet own them. Exploitable minerals on the CS consist of three basic forms: (i) in situ minerals such as coal found within the rock strata; (ii) placer deposits of heavy minerals and elements, such as gold, which may accumulate with the seafloor sediments; and (iii) the sand and gravel located on the sea floor. In situ mines operating beneath the sea (as on Cape Breton Island) usually begin on land and follow the resource out beneath the sea; rarely does the mine extend out beyond the TS limit. Subsea placer deposits are not yet extensively exploited. Sand and gravel probably hold out the greatest potential, for the technology is simple, recovery costs are low and the need for building materials is great. Coastal States have the exclusive right to explore and exploit these subsea minerals on the CS. The situation is slightly different for those regions of the CS extending beyond 200 miles. There, the coastal State exploiting the mineral resource must annually pay all State Parties to the Agreement 1% of the annually produced resource during years 6 through 12 of production and 7% annually, thereafter. The deep sea-bed (DSB) is that portion of the seafloor which resides seaward of the continental shelf, usually many thousand of metres below sea level. Metallic accretions, known as manganese nodules,(34) have been discovered on the DSB and are potentially of enormous value. Once this vast resource was found, efforts were undertaken to prevent these nodules from being scooped-up by the few rich, technologically-advanced nations that would soon be in the technological position to do so. Manganese nodules, many felt, could be used to reduce some of the discrepancies in wealth between the world's nations. The LOSC addresses this resource via the newly-formed DSB Regime. Part XI of the Agreement sets up an International Sea-Bed Authority (the "Authority") to coordinate and oversee the development of the mineral resources of the seafloor and subsea strata beneath the HS.(35) This portion of the seafloor is known in the LOSC as the "Area." General policy decisions regarding the Area are made by a two-thirds vote of the "Assembly," in which each state Party to the LOSC gets one vote. The Assembly is the principal organ of the Authority. Executive decisions implementing general policies are made by the Council, whose membership is voted upon by the Assembly, but is designed to represent Parties of all levels of economic development, social arrangement, major land-based producers of the minerals, major consumers of the minerals and all geographic regions. The physical mining operations of the Authority are to be undertaken by commercial operators and by an international business entity known as the "Enterprise," which would operate in the Area for the general benefit of mankind. Profits from the Enterprise would be divided equitably between the State Parties. The Enterprise is to be funded half by loan guarantees by State Parties in accordance with their relative U.N. assessments and half by commercial borrowing. It is anticipated that the operations of the Enterprise would eventually make it self-financing. The details of allocation of mining sites and production quotas are extremely complex and beyond the scope of this paper. The DSB is the element of the LOSC likely to have the greatest economic impact on the world in the long term. Though there are at present no operating DSB mining operations, several nations, including the United States, have refused to ratify the LOSC because of its DSB mining provisions. Without active participation by the world's major economic powers, the viability of a DSB mining venture as provided for in the LOSC is questionable. CONSERVATION OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT The international legal obligation to preserve and protect the marine environment predates the LOSC and has its genesis in the Trail Smelter Arbitration,(36) which says that no State may permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury to the territory of another. Principle 21 of the Stockholm Declaration,(37) commonly held to codify the (then) state of customary international law, extended this by urging States to ensure that "areas within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction." Clearly this encompasses damage caused by ships and damage to the High Seas. The LOSC reiterates this obligation, and makes the right to exploit natural resources subject to an overriding obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment. The LOSC defines "pollution of the marine environment" broadly, calling it

The Agreement contains provisions specifically dealing with marine pollution resulting from land-based sources, sea-bed activities within the TS or EEZ, vessels, and the atmosphere. There is also an obligation to establish rules regarding pollution resulting from deep sea-bed mining. Under the LOSC, jurisdiction to prescribe marine pollution standards is essentially the same as that discussed above under the title "State Jurisdiction Aboard Ships at Sea" and, with one important addition, is the same as that which existed prior to the Agreement. Flag States may set minimum standards to which their ships must adhere anywhere they travel. Coastal States may set standards within their TS. Port States may set standards for their harbours. However, all States with jurisdiction, whether flag, coastal or port, must "adopt laws and regulations for the prevention, reduction and control of pollution of the marine environment ... [which] shall at least have the same effect as that of generally accepted international rules and standards ..."(39) Such standards probably imply the major multilateral treaties respecting maritime pollution,(40) in effect, bringing Parties to the LOSC into line with these treaties that are not as widely accepted as the LOSC. 2. Monitoring Pollution and Risks The international obligation to monitor marine pollution is relatively weak. States need only, as far as practicable, monitor and scientifically evaluate the risks and effects of marine pollution. In effect, poorer States are held less accountable and the existence of an obligation to monitor outside of one's EEZ is debatable. The monitoring obligation does, however, pertain to both pollution and activities likely to pollute the marine environment. Although there is an obligation to make monitoring reports available to other States, many pollution risks will result from military operations, and these, one can safely assume, will tend not to be reported, or reported inadequately. The LOSC's general obligation is that, in preventing pollution, (i) States must take all necessary measures that are consistent with the LOSC; (ii) the appropriateness of measures taken may be limited by what is practical and the State's capacity; and (iii) States should endeavour to harmonize their policies. Arguably, the "all necessary measures" obligation includes an obligation to create rules designed to protect the marine environment prior to the occurrence of a polluting event. This would bring the LOSC in line with obligations pursuant to the HS Convention.(41) Section 5 of Part XII of the LOSC says "States shall adopt laws and regulations to prevent [marine pollution from several different sources]." Whether, based on the text of Section 5 alone, the term "shall" is mandatory or permissive, is not clear. Section 5 read in conjunction with the obligation to harmonize policies, however, strengthens the argument that "shall" is mandatory. States also have an obligation to cooperate regionally and globally for the establishment of international standards. Two major groups of States have the right and/or the obligation to legislate safeguards: coastal States and flag States. The right of the coastal State varies with the body of water (TS, EEZ, international strait, etc.) in question. In general, however, the regulations must be made public, and must not apply in a discriminatory manner or in areas beyond national jurisdiction,(42) or exceed generally accepted international standards. For instance, regulations purporting to stipulate ship design for ships travelling through the EEZ would probably exceed the coastal State's jurisdiction; ship design is more appropriately regulated by the flag State. Coastal State legislative jurisdiction within the EEZ and on the continental shelf is limited to laws pertaining to ocean dumping. Ice-covered areas within the limit of the EEZ receive special consideration under the LOSC's pollution control provisions. Within these areas, coastal States may legislate for the protection of the environment in a non-discriminatory fashion. This could be viewed as ex post facto approval of Canada's 1970 actions in proclaiming the Arctic Waters Pollution Protection Act,(43) which regulated shipping within 100 miles of Canada's Arctic coasts in an attempt to preserve the fragile environment. Prior to the LOSC, only flag States had jurisdiction to enforce breaches of marine pollution laws that occurred outside the TS. Since most transit, many accidents and virtually all intentional ocean dumping occurs outside TSs, however, a great deal of pollution took place without penalties being enforced. As well, countries offering flags of convenience had little incentive to prosecute pollution infractions by their ships; indeed, some of these countries attract registrations by systematically not prosecuting such action. Under the LOSC, however, flag States have an obligation to enforce their pollution laws. Although coastal States may set regulations regarding dumping within the EEZ and on the continental shelf, enforcement jurisdiction is limited. Often the coastal State must wait until the ship enters port. While the offending ship is in the EEZ, the coastal State may request information regarding the ship's identity, registration and next port of call. If there is significant pollution discharge or a substantial threat, the coastal State may inspect the vessel. Upon "clear objective evidence" of discharge threatening or causing major damage, the coastal State may detain the ship and institute legal proceedings. Such actions must be pursued cautiously, however, for States seeking to enforce pollution control laws may be responsible for losses resulting from the enforcement if the measures taken exceed those reasonably required in light of the available information. Coastal States have no enforcement jurisdiction on the HS, nor is there enforcement jurisdiction against warships; however, when commercial ships are in their ports, they may take action for breaches of international pollution standards that occurred outside the EEZ, including on the HS. The parties to the LOSC are States, so only States can be responsible under the Agreement for damage to the marine environment. The LOSC says that States are responsible "in accordance with international law." Succinctly, the law of State responsibility is that States are responsible for most(44) actions of their nationals (including corporations) exercising elements of governmental authority and State agencies. In a breach of an international obligation, such as provisions of the LOSC, the State is responsible for making reparations.(45) International law has long required that ships fly the flag of one State or, more recently and in limited circumstances, the flag of the United Nations or one of its constituent agencies. The LOSC retains this requirement. As discussed above, ships assume the nationality of the State whose flag they fly. Ships that fly the flag of more than one State are considered ships without nationality. Ships sometimes fly "flags of convenience"(46) rather than the flag of some State to which the ship, shipowners or crew have a long standing connection. The LOSC effectively permits flags of convenience by requiring only that there be a "genuine link" between the State and the ship. The genuine link standard is a reiteration of the law that existed prior to the LOSC, when flags of convenience abounded. B. Transit and Navigation Routes Rights of navigation were necessarily touched upon earlier, in the discussion of the territorial subdivision of the sea. As one moves landward from the HS, the navigational rights of the non-coastal State generally diminish. On the HS there is freedom of navigation. Within an EEZ, freedom of navigation is limited by the coastal State's safety zones (of up to a 500-metre radius around artificial structures) and pollution control legislation impacting upon navigation. Within a TS, foreign States have only a right of innocent passage, which may be limited if the coastal State stipulates sea-lanes that must be used while navigating or temporarily closes portions of the TS for reasons of security. As discussed earlier, international straits (for instance, Gibraltar) are subject to a right of transit, which, unlike innocent passage, need not be "innocent." Piracy laws, distinct from robbery laws, have existed for almost 2,500 years, making piracy the world's oldest international crime. Historically, piracy laws were justified by sovereigns claiming universal jurisdiction over their ships and a right to defend these ships wherever they might be. Hanging at sea was the penalty, which was usually quickly meted out. Pirates have historically been distinguished from privateers, who held a letter of marque from their sovereign, permitting them to plunder the enemies' commerce during times of war. Privateers who exceeded their commission from the sovereign, for example by attacking neutral commerce, were not considered pirates. Although international law has since abolished all distinction between privateers and pirates, tribunals in this century held that U-boat attacks on Allied merchant shipping during the World War I were not acts of piracy. The LOSC reiterates the law of piracy as set out in the HS Convention. Piracy now requires six specific elements. The act must: (i) be illegal; (ii) be committed by a private ship or aircraft (or a public craft if the crew has mutinied); (iii) be against another ship or aircraft; (iv) be in an area outside the jurisdiction of any State (usually, the HS); (v) be for private ends; and (vi) result in the detention of the craft or violence or depredation directed at the craft, its passengers or crew, or their property. The limiting requirement that there be an "illegal act" seems to permit acts of a piratical nature to take place with colour of right, as during a war. Interestingly, the LOSC leaves the nationality of pirate ships to domestic laws on ship nationality. Presumably, some States' laws may decree that an act of piracy strips the ship of its nationality and thus eliminates that State's international responsibility for the acts of the pirate ship. Warships that have reasonable grounds for suspecting that a ship (other than another warship) is engaging in piracy, have a right to board the suspected ship if it is on the HS. A similar right of boarding exists against the so-called "pirate broadcasters," which undertake unauthorized broadcasting based from positions on the HS. This broadcasting, which is not piracy per se, is of a class of prohibited activities akin to piracy. Canadian law adopts the international legal definition of piracy and punishes it as an indictable offence with possible life imprisonment.(47) Despite general statements in the LOSC that the HS shall be reserved for peaceful purposes, this provision is not adhered to by many (if any) States. The very existence of a navy may constitute a threat and therefore be a breach of the peaceful use provision. The LOSC also says that

Article 2(4) of the Charter, however, prohibits the use or threat of force by a State against any other State. This has led some to postulate that there may not be any legal military use of the seas.(49) The intermediate conclusion would be that marine military activities are regulated by the LOSC during peacetime, shifting to the law of warfare once hostilities have commenced. Warships(50) are exempt from many requirements of the LOSC pertaining to waters beyond the jurisdiction of any State. For instance, warships on duty for their States are exempt from the marine protection provisions of the Agreement. On the HS, warships have complete immunity against the enforcement of any State's jurisdiction. Within a coastal State's TS, warships have sovereign immunity from prosecution by the coastal State, although the LOSC does permit them to practise the marine equivalent of a declaration of persona non grata, by ordering the warship out of their TS. Four military activities take place on the seas: (i) aggressive warfare during hostilities; (ii) transit; (iii) manoeuvres and weapons testing during peacetime; and (iv) naval blockades, usually during tense periods prior to war. The first is part of the law of warfare and beyond the scope of this paper. Warship transit is regulated as for any other vessel: freedom of transit through international straits, on the HS and, arguably, EEZs. As discussed earlier, military vessels can likely meet the requirements of "innocent passage" and thereby have passage through a TS. Manoeuvres (including surveillance) and weapons testings definitely do not constitute innocent passage. Some military vessels, notably those carrying nuclear and chemical weapons, are regulated pursuant to multilateral or bilateral agreements, which many nations consider to be outside the purview of the LOSC. Apart from restrictions arising from specific arms treaties, military manoeuvres, including weapons use, constitute legitimate use of the sea under the LOSC. Naval blockades, such as those during the Cuban missile crisis and the recent Persian Gulf war, are popular military tools for bringing about political compliance. Blockades are, however, prima facie breaches of the LOSC as they interfere with freedom of navigation on the HS. The law of the sea does not, however, exist in isolation from all other international law; naval blockades may be legitimized if they are supported by a United Nations Security Council resolution under Chapter VII of the Charter. The blockade of Iraq had such authority;(51) the blockade of Cuba did not. A. Obligations regarding Resolution The LOSC incorporates the principles of the Charter of the United Nations in its approach to maritime disputes. Under the Charter, States have the following two obligations: to settle their differences, and to settle them by peaceful means. Disputes can be considered settled when they no longer endanger international peace, security and justice. Since every dispute is unique, international law leaves open the means to be chosen, and these may involve any peaceful measures accepted by the parties.(52) This openness is important. Although portions of the LOSC may be considered customary law, the detailed conciliation and arbitration provisions of the Agreement (discussed below) are unlikely to be considered to be so. Those provisions would not become effective until the Agreement came into force. B. Conciliation and Binding Arbitration Following a required exchange of views, disputing parties may, by agreement, enter into formal conciliation proceedings. Although the LOSC sets out how conciliators are to be chosen, the form of the report and the responsibility for costs, it leaves the actual conciliation process quite open. The parties are free to reject the recommendation of the conciliators. If either of the parties chooses not to go to conciliation or conciliation fails, either party may submit the matter to binding arbitration. When becoming a party to the LOSC, a State may, by written declaration, elect to choose a procedure for compulsory resolution of disputes pertaining to rights under the Agreement. Disputes can be resolved either on a legal basis or in equity. Parties are free to choose from among: the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (discussed below); the International Court of Justice;(53) an Annex VIII arbitration tribunal, where the subject of the dispute relates to fisheries, protection and preservation of the marine environment, scientific research or pollution;(54) or an Annex VII arbitration tribunal, the default choice. If the disputing parties have chosen different procedures, then, absent an agreement to the contrary, the dispute will proceed to Annex VII arbitration. In such arbitration, the disputing parties usually appear before a five-person tribunal chosen from a standing list of qualified arbiters. Each party may appoint one arbiter, the remainder are normally jointly chosen. The tribunal hears evidence and gives a final decision with reasons. There is no avenue for appeal. At any time, the parties may elect not to permit disputes involving any or all of the following areas to go to arbitration: delimitation of maritime boundaries, provided the parties accept the conciliation procedures; military activities; or matters over which the Security Council is exercising its functions.(55) 1. International Tribunal for the LOS The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (the "LOS Tribunal") is the standing tribunal for adjudicating international maritime disputes. The tribunal sits in Hamburg, Germany. The bench consists of twenty-one independent members, with the status of diplomats, who are elected by the State Parties by secret ballot. All are from different countries, and the bench must be globally representative of geography and the world's major legal systems. Members may not hear cases involving matters with which they have previously been associated, but are not required to remove themselves solely because the State of their nationality is a party to the dispute. Major adjudications usually entail the entire available bench, although the tribunal can sit in chambers of five, either on agreement by the parties or to deal with matters summarily. Disputes can be resolved either in accordance with international law including the LOSC or, if the parties agree, in equity. A judgment consists of a reasoned decision by a majority of the bench. There is no appeal process. The high cost and potential returns of commercial mining on the sea-bed(56) provide fertile ground for disputes. Parties to the mining venture may first attempt to agree on a mechanism for resolving a particular dispute regarding the interpretation of the LOSC as it pertains to the Area. If they cannot agree, the dispute will be referred to the Sea-Bed Disputes Chamber, which consists of eleven members of the LOS Tribunal, chosen by the LOS Tribunal. It operates in a manner similar to the LOS Tribunal but, in addition to international law, it also applies the rules, regulations and procedures of the Authority in its deliberations. Contractual disputes respecting mining in the Area are settled by arbitration in accordance with the UNCITRAL(57) rules.

(1) The first comprehensive work defining the law of the sea was the 1609 treatise Mare Liberum by Hugo Groitius. (2) Montego Bay, 10 December 1982, not yet in force, 21 I.L.M. 1245 (1982). This document stems from the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea; sometimes referred to elsewhere as UNCLOS, in this paper the Convention from the Third Conference is referred to exclusively as LOSC. UNCLOS I, UNCLOS II and UNCLOS III refer to the three conferences, respectively. (3) Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, Geneva, 29 April 1958, in force 10 September 1964, 516 U.N.T.S. 205 (the TS Convention); Convention on the High Seas, Geneva, 29 April 1958, in force 30 September 1962, 450 U.N.T.S. 82 (the HS Convention); Convention on the Continental Shelf, Geneva, 29 April 1958, in force 10 June 1964, 499 U.N.T.S. 311 (the CS Convention); and the Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas, Geneva, 29 April 1958, in force 20 March 1966, 599 U.N.T.S. 285 (the HS Fishing Convention). (4) In particular, see Article 38(1)(b) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. (5) 402 U.N.T.S. 71. (6) The term "coastal State" in this paper refers to the State whose coastline generates the sovereign or economic interest for the area of water under consideration. (7) The reader should be aware that not all consistent practice creates binding customary law for all States. Relevant States must not only consistently undertake a course of action, but must also be of the opinion that international law requires it. Even then, States that consistently object to this practice may not be held to be bound by the emergent customary law. (8) For a pictorial representation of these, see Figure 1. (9) For archipelagos only, the LOSC sets an upper limit of 125 miles for the length of any single straight baseline. It may be reasonable to conclude that this may develop into the upper limit for straight baseline projections in non-archipelagic situations as well. (10) For a pictorial representation of the territorial subdivisions discussed in this section, see Figure 2. (11) A nautical mile is about 14% longer than a statute mile, which is the linear measure used on land. Twelve nautical miles is slightly more than 22 kilometres. (12) Concomitant with this right of innocent passage is a restriction on the right of the coastal State to regulate shipping, such as the design of ships in their TS, or charging for passage so as effectively to preclude foreign ships. The coastal State may, however, adopt domestic standards comparable to internationally recognized standards. (13) Even this economic right is limited in two ways: (i) the coastal State must exercise this right with due regard to the right of other States (e.g., a right of passage); and (ii) access to excess fishing resources must be offered equitably to land-locked States within the region. (14) Still open, however, would be the question of grounded ice; that is, whether ice that extends down to the seafloor and is fixed to that seafloor should be considered land or water. (15) R.S.C. 1985, c. A-12. (16) See discussion below, under the heading "Dispute Resolution." (17) The equidistant point is the point that is an equal distance from the closest baseline of each of the disputing States. Although in the abstract an equidistant line gives an equitable result, especially for opposing coasts, it can be greatly affected by nearby but minor geographic features (such as a promontory close to the boundary) which deviate from the general coastal geography. (18) The Continental Shelf Case (Lybia v. Malta), 3 June 1985, 24 I.L.M. 1189 (1985), p. 1198. (19) Encroachment occurs when the seaward projection from one State's coast overlaps on the seaward projection of another State's coast. The non-encroachment principle contends that boundaries should be drawn so as to minimize overlap. (20) Higher "degrees of overlap" occur when the frontal projection of more than one geographically separated coast overlaps with the frontal projection of another State. For instance, projections from both Nova Scotia and Newfoundland overlap with the single projection from the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon. (21) Theoretically, should a sector theory meet with international acceptance, Canada and Russia would have a point-sized maritime boundary at the North Pole. (22) A Chamber of the Court is some portion (but not all) of the Court, chosen by the Court, sitting to hear a particular case or a particular class of cases. The full ICJ contains 15 judges. The Chamber in the Gulf of Maine case consisted of five judges. For a review of the operations of the ICJ, see E.M. LeGresley, The World Court, Library of Parliament, BP-17E, July 1992. (23) The Gulf of Maine Case, (Canada v. U.S.A.) Order Constituting the Chamber, 21 I.L.M. 69 (1982), par. 1. (24) English Channel Arbitration, 18 I.L.M. 397 (1979). (25) Enclaving consists of allocating to one State territorial rights to waters which exist entirely within the waters of another State. It is most likely to occur when a small island is located adjacent to the coast of a larger State located on a continent. By definition, enclaving can only result when the enclaved State receives less marine territory than the adjacent State (such as a narrower EEZ). (26) The representatives of both Canada and France on the tribunal dissented with the opinion of the majority. (27) The partially offshore oil field at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, by far the largest oil field in the United States, is very close to the disputed area in the Beaufort. The Prudhoe Bay field is an order of magnitude larger than the Hibernia field. (28) Convention between Great Britain and Russia concerning the Limits of their Respective Possessions on the North-West Coast of America and the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, 16 February 1825, 75 C.T.S. 95. Russia held Alaska until it was ceded to the United States in 1867. (29) See D.R. Rothwell, Maritime Boundaries and Resource Development: Options for the Beaufort Sea, Canadian Inst. of Resources Law, 1988. (30) The HS Fishing Convention, note 3. International Convention for the High Seas Fisheries of the North Pacific Ocean, Tokyo, 9 May 1952, in force 12 June 1953, T.I.A.S. 9242 236. (31) Sedentary species are those life forms which, at harvestable stage, are either immobile or unable to move except when in constant physical contact with the sea-bed or subsoil. Clams and crabs are sedentary, fish are not. The status of lobsters is unclear, for although they move almost exclusively by being in contact with the sea-bed, they can, for brief periods, move in the water column near the sea-bed. (32) Notably, Principle 21 of the Stockholm Declaration, see note 37, and associated text. (33) For example, the Canada/U.S.A. Treaty Concerning Pacific Salmon, Ottawa, 28 January 1985, in force 18 March 1985. (34) "Manganese nodules," actually contain substantial amounts of nickel and copper. Canada, as the world's major producer of nickel and a substantial producer of copper, is likely to see the economics of running land-based operations for the mining of nickel and copper affected once DSB mining is under way. (35) See the chapter entitled "Sea-Bed Disputes Chamber," for a discussion of dispute resolution involving DSB mining operations. (36) U.S.A. v. Canada (1941) 3 R.I.A.A. 1905. (37) U.N. Doc. A/Conf. 48/14, (1972), 11 I.L.M. 1416, adopted 16 June 1974. (38) LOSC, Article 1.(4). (39) LOSC, Article 211(2). (40) Examples would likely include, inter alia, the HS Convention, supra, note 3; the 1969 International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution Casualties (the Intervention Convention), 9 I.L.M. 25 (1969), neither signed or ratified by Canada, in force 1972; the 1969 Convention For Oil Pollution Damage (the Civil Liability Convention), 9 I.L.M. 45 (1970), acceded to by Canada 24 April 1989, in force 1975; the 1972 London Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes at Sea (the London Dumping Convention) 11 I.L.M. 1291 (1972), in force for Canada 13 November 1975; and the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, (the MARPOL Convention), 12 I.L.M. 1319 (1973), in force 1983, Canadian accession to take effect 16 February 1993. Less likely included would be any of the regional treaties dealing with pollution in the Mediterranean Sea, the North Sea or the Baltic Sea, or any bilateral agreements. (41) Article 24 of the HS Convention says, in part, "[e]very State shall draw up regulations to prevent pollution of the seas ..." (42) The term "jurisdiction" is used broadly here to include those areas in which States have some exclusive rights, including the EEZ. (43) See note 15. (44) In the famous Home Missionary Society Claim (U.S.A. v. Great Britain (1920), 7 Moore's Int'l L. Dig. 956) the tribunal held that governments are not responsible for rebellious acts in violation of authority where the State is not in breach of good faith or negligent in its attempts to suppress the rebellious acts. From this decision one could conclude that Canada should not be responsible to the United Kingdom for the 1970 detention of a British diplomat by the F.L.Q., provided Canada was not negligent in its duty to protect diplomats in Canada or suppress terrorism within Canada. More recently, however, the International Law Commission seems to argue that even this defence should be trimmed back in cases of the acts of State organs. Article 10 of the Draft Articles on State Responsibility (2 Y.B.I.L.C. 90 (1979)) says that acts of State organs are acts of the State even if the organ disobeys instructions or exceeds its authority. (45) Chorzow Factory Case (Indemnity) (Merits), Germany v. Poland (1928), 17 P.C.I.J. Rep. Series A 29. (46) Flags of convenience provide hard currency earnings to those States, such as Liberia and Panama, which offer them. In exchange for the registration fees, the State assumes international responsibility for the ship's actions. Typically, only very poor States offer themselves as States of convenience. Considering that damages from some spills could be very great, flags of convenience are a means whereby shippers may effectively seek to avoid some avenues of redress against them. (47) Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, section 74(1). Criminal Code section 75 also sets out the more loosely-defined offence of a "piratical act," with penalties of up to 14 years' imprisonment. (48) LOSC, seventh preambular paragraph. (49) R.R. Churchill and A.V. Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 2nd ed., Manchester University Press, Manchester, U.K., 1988, p. 307. (50) The LOSC defines a "warship" as a ship belonging to the armed forces of a State, bearing distinguishing external marks, under the command of a duly commissioned officer of the State and manned by an armed forces crew. (51) U.N.S.C. Res. 665 of 25 August 1990 and U.N.S.C. Res. 670 of 25 September 1990. (52) See Article 33(1) of the Charter of the United Nations. (53) See note 20. (54) Annex VIII arbitration tribunals operate like other arbitrations under the LOSC, with the addition of technical experts in each of the relevant disciplines. They may function primarily as fact-finding bodies. (55) See, in particular, Articles 33 to 38 of the Charter. (56) See discussion of deep sea-bed mining and the "Area" under the chapter titled "Deep Sea-Bed Minerals", p. 28. (57) United Nations Commission on International Trade Law Arbitration Rules, U.N.G.A. Resolution 31/98 of 15 December 1976. |