BP-327E

NORTH AMERICAN FREE

TRADE AGREEMENT:

RATIONALE AND ISSUES

Prepared by:

Anthony Chapman

Economics Division

January 1993

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

CANADA-UNITED STATES-MEXICO TRADE AND INVESTMENT PATTERNS

NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE: THE RATIONALE

C. The United States' Rationale

C. Worker Rights, Occupational Health and Safety

APPENDIX 1: THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE NAFTA

NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT: RATIONALE AND ISSUES

The announcement on 11 June 1990 by U.S. President Bush and Mexican President Salinas of their countries' intention to enter into negotiations leading to a free trade agreement presented the Canadian Government with a dilemma. Canada had just undergone a divisive national debate over the 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement culminating in an election fought over the issue. Should the Government bring Canada into the negotiations and risk re-igniting anti-free trade passions? On the other hand, could Canada afford to stand aside while the U.S. negotiated a separate Agreement with Mexico that threatened to erode some of the gains that this country had achieved in the earlier bilateral negotiations?

On 5 February 1991, Canadian Prime Minister Mulroney, Mexican President Salinas and U.S. President Bush announced the decision to pursue full trilateral negotiations to achieve a North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). With 361 million people and a combined GDP of C$7,500 billion, the new trading bloc would be larger than the European Community.(1) The negotiations were formally launched in Toronto on 12 June 1991 by international trade ministers from the three countries. Just over one year later (12 August 1992) agreement in principle on NAFTA was reached. The legal text was formally signed by the leader of each NAFTA country on 17 December 1992.

This paper begins with an outline of the triangular trade and investment relationships between Canada, the United States and Mexico. The relatively modest commercial links between Canada and Mexico mean that the economic gains to Canada from the NAFTA are also likely to be small, at least initially. This suggests that Canada's rationale for entering the NAFTA negotiations was primarily defensive in nature.

The negotiation of a free trade agreement with a developing country like Mexico raises several important issues that did not arise during the 1987 bilateral negotiations with the U.S. Mexican wages are roughly one eighth the earnings of Canadian or U.S. workers. What effect will free trade have on employment and wages in the two high-income countries? Mexico's worker health and labour standards are more lightly enforced than those in Canada and the United States. Will the NAFTA lead to exploitation of Mexico's labour force and the lowering of Canadian and U.S. labour standards in order to compete?

Partial free trade under the Maquiladora program has had serious consequences for the environment, especially in the U.S.-Mexico border area. What effect will the NAFTA have on the environment both in Mexico and across the border in the United States? Underlying these issues is the fear that firms will migrate to Mexico to exploit the cost advantage resulting from the country's low wages and lax enforcement of labour and environmental standards.

Some other evidence suggests that the links between the NAFTA, foreign investment outflows and domestic employment may be more complex than had been supposed. Finally, the paper discusses some of the potential problems raised by the NAFTA for outside countries. As with the "Europe 1992" program, fears of a "Fortress North America" may be exaggerated. A summary of the NAFTA's main elements is provided in the appendix.

CANADA-UNITED STATES-MEXICO TRADE AND INVESTMENT PATTERNS

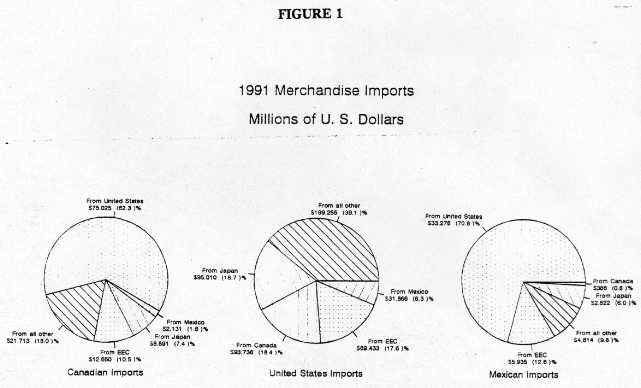

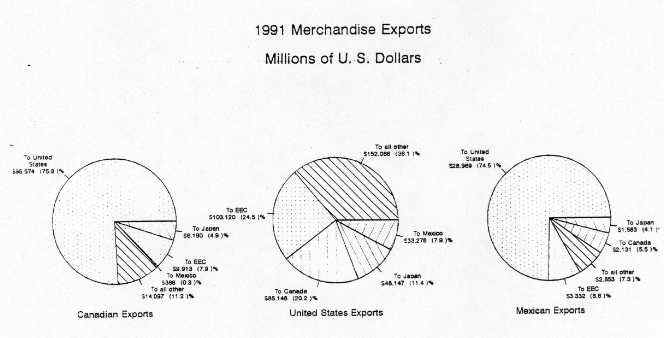

The United States is the largest trading partner of both Canada and Mexico. Canada is the United States' largest trading partner and Mexico is the third largest. Still, most U.S. trade is with countries outside North America (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). In 1991 Canada and Mexico both shipped about 75% of total merchandise exports to the United States.(2) Over 70% of Mexico's merchandise imports arrived from the U.S. in 1991, compared to 62% of Canada's imports.(3) Investment links follow a similar pattern, with the United States providing about two-thirds of the foreign direct investment in Canada and Mexico.

TO

SEE THIS FIGURE, PLEASE REFER TO THE PRINTED COPY OF THIS DOCUMENT,

WHICH YOU MAY REQUEST BY DIALING 996-3942

FIGURE 2

TO

SEE THIS FIGURE, PLEASE REFER TO THE PRINTED COPY OF THIS DOCUMENT,

WHICH YOU MAY REQUEST BY DIALING 996-3942

By contrast, Canada-Mexico commercial links are much less developed. In 1991 Canada exported only C$524-million worth of merchandise to Mexico and imported C$2.6 billion in return.(4) These represented just 0.4% of Canadian exports and 1.9% of imports. The highlights of Canadian trade with Mexico and the United States are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

|

TABLE 1 |

|||

|

CANADIAN TRADE WITH MEXICO IN 1991 (MILLIONS OF $C) |

|||

| Exports to Mexico | Imports from Mexico | ||

| Motor Vehicle Parts |

153.5 |

Motor Vehicles & Parts |

1,439.3 |

| Iron & Steel Prod. |

46.3 |

Engines and Parts |

340.0 |

| Newsprint |

34.5 |

Radio, Audio, Telephone |

143.2 |

| Wheat |

25.0 |

Computers & Parts |

127.2 |

| Telecom. Equipment |

23.0 |

Petroleum Oils |

97.6 |

| Paper Products |

18.9 |

Fruits, Nuts & Coffee |

76.0 |

| Sulphur |

18.9 |

Air Cond. & Other Equip. |

58.3 |

| Aircraft and parts |

18.6 |

Vegetables |

48.5 |

| Petroleum Oils |

16.1 |

Carpets, Yarn & Fabric |

30.1 |

| Asbestos |

16.0 |

Kitchen Appliances |

23.3 |

| Total Exports |

524.5 |

Total Imports |

2,579.8 |

| Source: Government of Canada, North American Free Trade Agreement: The NAFTA Partnership, August 1992 | |||

|

TABLE 2 |

|||

|

CANADIAN TRADE WITH THE U.S. IN 1991 (MILLIONS OF $C) |

|||

| Exports to the U.S. | Imports from the U.S. | ||

| Autos & Chassis |

16,438 |

Motor Vehicles & Parts |

10,148 |

| Trucks & Chassis |

7,088 |

Autos & Chassis |

6,988 |

| Motor Vehicle Parts |

6,533 |

Computers |

4,330 |

| Crude Petroleum |

5,974 |

Trucks & Chassis |

2,463 |

| Newsprint |

5,165 |

Telecoms & Equipment |

2,320 |

| Telecoms Equipment |

4,185 |

Motor Vehicle Engines |

2,018 |

| Natural Gas |

3,511 |

Semi-conduct. & Equip. |

1,540 |

| Softwood Lumber |

3,055 |

Plastic Material |

1,394 |

| Petroleum & Coal Prod. |

2,994 |

Misc. Equip. & Tools |

1,344 |

| Wood Pulp |

2,243 |

Organic Chemicals |

1,271 |

| Total Exports |

103,462 |

Total Imports |

86,299 |

| Source: Government of Canada, North American Free Trade Agreement: The NAFTA Partnership, August 1992 | |||

The data on trade in services between Canada and Mexico are incomplete. However, trade in business services only was modest -- C$54 million (1990) of business services exported to Mexico and C$33 million (1990) of business services imported. (By comparison Canada exported about C$5.0 billion of business services to the U.S. in 1990 and imported C$8.3 billion in such services from the U.S.).(5)

Canadian direct investment in Mexico in 1990 amounted to C$175 million while Mexican direct investment in Canada was just C$1 million. The stock of Canadian direct investment in the U.S. amounted to C$53.1 billion in 1990 while the stock of U.S. direct investment in Canada was C$80.4 billion.(6)

The United States sold US$33.3 billion worth of goods to Mexico in 1991 and imported US$31.2 billion. Almost one quarter of this trade(7) is linked to the Maquiladora program under which Mexico permits U.S. parts and components to enter duty-free for further processing before re-export to the United States. When the finished goods re-enter the United States, duty is applied to the Mexican value-added only; the U.S. portion of the product's value is exempt from duty.

Since the program began in 1965 the size of the maquiladora sector has increased from a few plants to over 2,100 facilities employing almost 470,000 Mexican workers.(8) So far, Canadian firms have not been significant participants in the Maquiladora program but six Canadian companies are said to be operating eight plants employing about 3,000 people, mainly in the auto parts industry.(9) The largest Maquiladora industries include: electric and electronic goods; textiles and apparel; furniture; and transportation equipment.

NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE: THE RATIONALE

Given Canada's relatively modest trade flows with Mexico, it would have been understandable if the Canadian government had declined to join the NAFTA negotiations, especially given memories of the recent rancorous debate over the Canada-U.S. FTA. It soon became apparent, however, that standing aside while the U.S. and Mexico worked out their own bilateral deal did hold some risks for Canada, particularly if other Latin American countries negotiated free trade deals from which Canada was also excluded.

If the United States were to negotiate a bilateral free trade agreement with Mexico without including Canada, the U.S. would be the only country of the three that had preferential access to both the Canadian and Mexican markets. Such a trading arrangement has been referred to as "hub-and-spoke," since one country (the hub) has preferential access to both of the other countries' markets (the spokes) but the spoke countries have free access only to the hub country's market.(10)

The first risk this holds for Canada, trade diversion, stems from displacement of Canadian goods in various markets. In the Mexican market, U.S. goods would enter duty-free while Canadian products would not enjoy that privilege. With respect to the U.S. market, Canadian goods would be out-competed by American manufacturers utilizing lower-priced Mexican components to which Canadian producers did not have preferential access. Furthermore, if Mexico were able to negotiate more favourable access in some areas than Canada had achieved under the FTA, additional Canadian exports could be displaced from the U.S. market.(11)

Investment could also be diverted under a hub-and-spoke trading arrangement. Multinationals would prefer to invest in the United States (the hub), since only that location would provide barrier-free access to all three countries. Investment in a spoke country, such as Canada, would provide free access to only two markets -- the domestic market and the U.S. market. If additional Latin American countries were added to the hub and spoke arrangement, the risk of trade and investment diversion for Canada would become greater.

Finally, the potential of the Mexican market has to be considered. Although Mexico's GDP per capita is only about one sixth that of Canada and the United States, it has a population of 81 million persons generating total purchasing power equal to about 13 million Canadians, or a market that is almost half the size of Canada's. If the Mexican economy achieves growth rates similar to those exhibited by Portugal and Spain after joining the EC, Mexico's purchasing power could become significant.(12)

Mexico's several reasons for wanting a free trade agreement are also economic in nature. Three quarters of Mexican exports are already shipped to the United States. Mexico's export-led strategy depends on maintaining and improving access to the U.S. market, which is unmatched by any other for size, openess and proximity.

Access to the U.S. market would be maintained through a dispute settlement mechanism dealing with U.S. anti-dumping and countervailing duty actions. The NAFTA would improve access by removing U.S. tariff and non-tariff barriers and it would equalize the advantage gained by Canadian exporters under the earlier bilateral FTA.

Foreign investment has been described as the "oxygen" of Mexican President Salinas' economic strategy. The NAFTA would help spur inflows of foreign direct investment in those sectors where Mexico has a comparative advantage. This would create employment for Mexican workers in an economy where it is estimated that one million new workers enter the labour force each year.(13)

Mexico also continues to depend on inflows of foreign capital and the return of flight capital to finance its approximately US$100 billion foreign debt and balance its current account deficit, which is expected to remain sizable over the foreseeable future. By locking in recent Mexican economic reforms,(14) a NAFTA would reassure foreign and domestic investors that the country would not retreat once more into protectionism and excessive government economic involvement.

C. The United States' Rationale

For the United States, the NAFTA has both political and economic implications. From a political standpoint, it is in the U.S. interest to have an economically strong and politically stable southern neighbour. A free trade agreement would help achieve both ends by reinforcing Mexico's recent economic reforms and stimulating economic growth through trade liberalization. As economic growth raised Mexican wages and employment, eventually the flow of illegal immigration to the U.S. from Mexico would likely abate.

Mexico is already the United States' third largest trading partner. With a population of 81 million people the country has the potential to grow into an even more important market for U.S. goods. Although the NAFTA is unlikely to have a major immediate overall economic impact on the U.S., it would open up opportunities in certain sectors for U.S.-based companies, particularly in industrial equipment as Mexico modernizes its capital stock. For U.S. multinationals, a NAFTA would entrench recent Mexican reforms, which liberalized foreign investment restrictions and protected intellectual property.

Finally, free trade with Mexico would put into practice the U.S. policy of "trade not aid" to assist developing countries. It would also advance former U.S. President Bush's "Enterprise for the Americas" initiative, setting the stage for free trade agreements with other Latin American countries.

Just as individuals, or regions within a country, gain from emphasizing the production of what they do relatively well and trading for those items they produce less efficiently, so it is for entire nations. The idea that countries benefit from trade liberalization is one of the most resilient principles of economics.(15)

The economic benefit from freer trade can be decomposed into gains that are "static," or one-time, and gains that raise the country's capacity to grow -- the so-called "dynamic" gains. Static gains derive from: exploitation by a country of its comparative advantage -- that is production of items that a country does relatively well; lowering prices for consumer goods and industry inputs; and economies of scale from firms expanding production to reach a larger market.

In contrast to static gains, which are once-and-for-all phenomena, dynamic gains actually raise the annual growth rate of an economy. Dynamic gains are more difficult to estimate because they are driven by factors such as human capital accumulation, research and development, and business uncertainty, which are not easily incorporated in economic models. Without taking into account dynamic gains from trade, it is estimated that the NAFTA would raise Canadian economic welfare by 0.03% of GDP. Mexican welfare would rise by 1.6% and United States' welfare by 0.07%(16)(Table 3).

Once dynamic gains assumptions about technical change are built in, the benefit to Mexico increases substantially to 5.0% of GDP, although gains remain modest for Canada and the United States, at 0.06% and 0.2% of GDP, respectively. Other studies suggest that the benefits to Mexico from NAFTA may be even higher. For example, a simulation by Robert McCleery and others found that, with improved investor confidence and productivity growth, free trade would raise Mexican welfare by 11% by the year 2000.(17)

The reason that Canada and the United States do not benefit more from free trade is the relatively small part that trade with Mexico currently plays in each country's economy. In Canada's case two-way trade of about C$3.1 billion between the two countries in 1991 represented less than 0.5% of Canadian GDP. Although United States-Mexico trade flows were substantially larger (US$65.1 billion), in the context of a US$5.7-trillion U.S. economy they represent only slightly over 1% of GDP.

|

TABLE 3 |

|||

|

LONG-TERM WELFARE

IMPROVEMENTS FROM NAFTA |

|||

|

Canada |

U.S. |

Mexico |

|

| a) Trade liberalization only: | |||

| Brown-Deardoff-Stern study(18) |

0.03 |

0.07 |

1.6 |

| Cox-Harris study |

0.03 |

- |

- |

| b) Trade and investment liberalization: | |||

| Brown-Deardoff-Stern study |

0.06 |

0.2 |

5.0 |

| Source: Dept. of Finance, The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment From a Canadian Perspective, November 1992 | |||

The average Mexican manufacturing wage is $2.31 an hour, or about 13% of the average Canadian manufacturing wage of $17.43.(19) Can Canada compete with low Mexican wages or will footloose industries pull up stakes and move their operations to Mexico? Is competition with low-wage Mexico likely to drive down wages and employment here in Canada?

When considering relative competitiveness, it should be kept in mind that labour costs comprise only part of the cost equation - on average just 18% of total manufacturing costs, according to the Canadian Manufacturers' Association.(20) Much of the Mexican low-wage advantage is also offset by low worker productivity in that country. The Department of Finance estimates that in 1989 the average Canadian worker was 6.5 times more productive than his or her Mexican counterpart.(21) Moreover, Canada's cost of capital per unit of production was only 47% of that of Mexico(22) counterbalancing much of the remaining Mexican low-wage edge. Finally, Canada has a distinct advantage in other, non-quantifiable factors which influence costs, such as the state of technology and availability of infrastructure.

The three published studies on the impact of a NAFTA on the Canadian economy use computable general equilibrium models (CGEs) which represent the economy in mathematical form. In order to "clear" the labour market, these economic models either fix aggregate employment levels and allow the aggregate average wage rate to adjust, or they peg the real wage and let employment levels adjust.

Two of the economic simulations of a NAFTA suggest that, contrary to standard trade theory,(23) the aggregate average wage rate in Canada would rise by 0.4%-0.5%. Canadian aggregate employment in these studies would remain unchanged by assumption. A third study, which assumes a fixed real wage rate, estimates that a NAFTA would raise aggregate employment by 0.61% to 11.02%, depending on the policy scenario. These Canadian studies accord with most simulations of NAFTA's impact on the United States, which show either an increase in aggregate real wages, or a rise in aggregate employment.(24)

The NAFTA's effect on particular labour market segments is more problematic. Some U.S. studies that differentiate the labour force according to skill levels indicate that a NAFTA would reduce real wages for U.S. unskilled labour; other U.S. studies show wage increases for both skilled and unskilled labour.(25) The United States International Trade Commission has concluded that "existing research does not provide a basis for definitive conclusions regarding the effect of a NAFTA on different components of the U.S. labour force, and further research is needed in this area."(26)

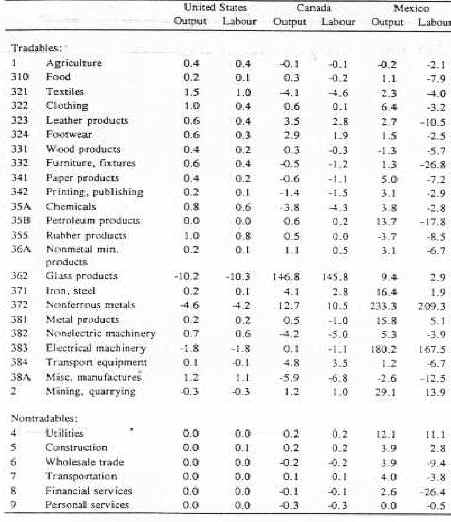

Table 4 shows expected sectoral production and employment changes due to the formation of a NAFTA. However, this study should be used with a degree of caution since it was undertaken prior to the completion of NAFTA negotiations and therefore does not reflect the shape of the final agreement, including the various sectoral agreements. Nor does it separate the impact of the Canada-U.S. FTA from the effects of the NAFTA.

In general, one would expect that less-skilled, less-educated workers in Canada and the United States would be most affected by free trade with Mexico. Labour-intensive activities, such as textiles, apparel and certain manufacturing assembly, are often cited as candidates for competition from Mexican imports. On the other hand, skilled workers in industries like telecommunications, computers and computer applications, and transit equipment, may gain from a NAFTA.

Eventually, Mexican wages are likely to rise closer to Canadian wages as Mexican labour productivity increases and the economy grows, but this may take some time. Mexico's relatively young population is adding one million new workers to the labour force each year. Also, Mexico has begun to reform the ejidos system of land tenure, which will lead to consolidation of the small farm plots into more efficient economic units. This restructuring is likely to displace a large number of workers from agriculture into other industries. Combined with Mexico's fast-growing population, this will provide a large pool of available labour, which could hold down wages in Mexico. If so, pressure on the wages and employment of Canadian and U.S. low-skilled workers may continue over the next decade.(27)

TABLE 4

Per Cent Changes

in Production and Employment by Sector

due to the Formation of a North American Free Trade Area*

*Sectoral results

apply for scenario 2, described in the text.

Source: Drusilla Brown, "An Overview of a North American Free

Trade Agreement" in William G. Watson, North American Free trade

Area, (Kingston, Ontario: John Deutsch Institute for the Study

of Economic Policy, 1991), p. 8.

TO

SEE THIS TABLE, PLEASE REFER TO THE PRINTED COPY OF THIS DOCUMENT,

WHICH YOU MAY REQUEST BY DIALING 996-3942

It is well established that trade liberalization raises overall economic welfare. On the other hand, freer trade is also bound to have distributional effects as capital and labour are displaced from industries where Canada does not hold an international comparative advantage. Wages and employment in low-skilled occupations, already under pressure from other developing country imports, may face additional erosion from the NAFTA.

In order to facilitate the smooth transfer of displaced workers into new higher-skilled sectors where Canada does have a comparative advantage, Canadian governments should ensure that sufficient investment has been made in worker retraining, as opposed to income maintenance programs. This issue is relevant, not only to the NAFTA, but in the context of the ongoing multilateral trade negotiations in which Canada is an active participant.

Environmental concerns about the NAFTA involve several issues: 1) whether Canadian and U.S. firms would migrate to Mexico to take advantage of that country's lax enforcement of environmental standards; 2) whether lax Mexican standards would place pressure on U.S. and Canadian jurisdictions to compromise their environmental standards; 3) the effect of NAFTA-generated economic activity on the environment both in Mexico and across the border.

Some of Mexico's environmental problems are notorious. For example, hundreds of deaths each year are attributed to Mexico City's air pollution. However, environmental problems are also serious in the cities of Guadalajara and Monterey and near the U.S. border where the Maquiladora industries have been expanding rapidly. Sources of pollution in the border area include: inadequate sewage treatment (many Mexican cities have none); industrial solvents have contaminated ground water and rivers; and open air dumping of municipal waste has caused air and water pollution. Extrapolating from Mexico's current pollution problems, some of which can be attributed to the Maquiladoras' expansion, suggests that the NAFTA might cause further degradation of Mexico's environment.

The problem is not Mexico's environmental legislation as much as the lax enforcement of these laws because of inadequate resources. Making environmental protection a priority, President Salinas has launched a broad cleanup program. One well publicized measure involved closing down the country's largest oil refinery, which employed 5,000 workers but was responsible for 15% of Mexico City's industrial air pollution.(28) Between March 1988, when Mexico's new environmental laws were introduced, through the end of 1991, a total of 1,926 plants were shut down pending compliance with environmental standards.(29)

The budget of Mexico's environmental agency, SEDESOL, has been increased and more environmental inspectors have been hired, raising the number from 19 inspectors initially, to 119 in 1991, and 200 inspectors in 1992.(30) As part of the "Integrated Border Plan," a joint Mexican-U.S. plan to clean up the border area, Mexico is spending US$460 million on sewage systems and waste-water plants; solid waste collection, treatment and disposal; road construction; public transportation and other measures.(31)

A United States Trade Representative study found that NAFTA was unlikely to result in a widespread migration of firms to Mexico "because relatively few firms meet all of the conditions required for profitable pollution haven investment: high environmental compliance costs, a big change in locational incentives as a result of removal of trade barriers, low costs associated with new investment, and actual differences in environmental compliance costs."(32)

The review by the Canadian government of NAFTA's environmental impact also found little evidence that firms migrate to pollution havens.(33) If indeed "dirty" industries do not migrate, then pressures to lower Canadian and U.S. standards seem less likely. It also relieves some, but not all, of the concern about NAFTA's effects on the Mexican environment.

Some environmentalists, for example, have suggested that NAFTA-induced growth will tax Mexico's already burdened environment. A study by Grossman and Kreuger comparing a number of countries found that, at low levels of income, economic growth tended to worsen air pollution, according to two measures.(34) However, after GDP per capita reached about US$4,000 - US$5,000, air quality began to improve.(35) The authors further suggested that Mexico's comparative advantage under a NAFTA may lie in labour-intensive and agricultural activities, which are relatively less polluting than capital-intensive industries. To the extent that free trade encourages a shift of resources into these sectors, the NAFTA would tend to reduce Mexico's pollution.

NAFTA environmental issues became prominent during the U.S. Congressional debate over extending the President's fast-track trade negotiating authority. Awareness of the relationship between trade and environmental issues was also heightened by a 1991 GATT dispute settlement panel ruling against a U.S. law banning imports of Mexican tuna because too many dolphins were being trapped in the nets. Pressure from environmentalists and U.S. legislators forced the NAFTA negotiators to address "green" issues directly in the text of the Agreement rather than in other forums.

The NAFTA preamble commits the three countries to environmental protection and conservation, to promoting sustainable development, and to strengthening the development and enforcement of environmental laws and regulations.(36)

The trade provisions of international environmental agreements on endangered species, ozone-depleting substances, and hazardous wastes, will take precedence over the NAFTA, subject to a requirement to minimize inconsistency with the NAFTA.(37)

The NAFTA affirms each country's right to choose its own appropriate level of protection of human, animal or plant life or health, the environment or consumers.(38)

Each country shall use international standards as a basis for its own sanitary and phytosanitary and standards-related measures but may adopt or maintain more stringent measures than those set internationally.(39)

The NAFTA countries will work jointly to enhance the level of safety and protection of human, animal and plant life and health, the environment and consumers.(40)

The Agreement states that no NAFTA country should lower its health, safety or environmental standards in order to attract investment.(41)

Where a dispute over a country's standards raises factual issues concerning the environment, that country may elect to have the dispute settled under the NAFTA dispute settlement procedures, rather than under another trade agreement or specified environmental agreements.(42)

NAFTA dispute settlement panels can call on scientific experts, including environmental experts, to provide advice on factual questions concerning the environment and other scientific matters.(43)

The complaining party bears the burden of proving that another NAFTA country's standards-related measure is inconsistent with the NAFTA.(44)

Although the National Wildlife Federation has called the NAFTA "the greenest trade treaty ever negotiated,"(45) the Agreement has been criticized by other environmental groups, including Greenpeace, Pollution Probe, the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth. Critics question whether the Agreement's preamble, including its "green" objectives, is legally binding. They also argue that the NAFTA does not establish minimum environmental standards to prevent ecological dumping. The Agreement does propose the harmonization of standards but critics fear this will lead to adoption of the lowest common denominator. Although the NAFTA gives precedence to certain environmental agreements, it requires signatories to minimize inconsistencies with the NAFTA. This implies that a country implementing an international environmental agreement would have to show that a trade measure contrary to the NAFTA was the most effective and reasonable means available.(46) Dispute settlement panels may call in environmental experts but there is no requirement to do so.

Former President Bush's request for EPA funding in FY1993 includes US$179 million for border-area environmental protection. Including proposed spending by other agencies, the U.S. government is committed to spending more than US$240 million in protecting the border area environment.(47) Under the Canada-Mexico Agreement on Environmental Co-operation signed in March 1990, Canada has contributed $900,000 to fund a municipal-industrial waste disposal feasibility study and $1 million to assist Mexico with environmental monitoring and enforcement.(48)

House of Representatives Majority Leader Richard Gephart and Congressman Robert T. Matsui have each proposed some form of cross-border tax or fee to help fund environmental protection.(49) Other bills introduced in the U.S. Senate, although not explicitly linked to the NAFTA, would also have implications for trilateral trade and the environment.(50) President Bill Clinton has indicated that, while more needs to be done to protect the environment (as well as U.S. jobs and worker rights), he believes that this can be accomplished in side agreements. President Clinton has also promised to establish a U.S.-Mexico commission to enforce environmental standards on both sides of the border.(51)

President Salinas has proposed a special economic support fund, to which Canada and the United States would contribute, to pay for infrastructure and environmental protection in Mexico.(52) The proposal resembles the European Social Fund, which has transferred financial resources to the EC's poorer members, such as Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Greece. Although aid has not yet been formally requested of Canada, International Trade Minister Wilson has stated that this country has no intention of providing Mexico with such financial assistance.(53)

C. Worker Rights, Occupational Health and Safety

Some Canadian and U.S. labour groups are concerned that firms may migrate to Mexico to exploit that country's lax labour standards. This might lead to a worsening of working conditions in the Mexican export industries. A related issue is whether there will be pressure to harmonize down labour standards in Canadian and U.S. jurisdictions.

Overall, Mexico's labour legislation is comparable with that of Canada and the United States.(54) As with environmental concerns, however, the problem is not Mexico's laws, but rather their weak enforcement. This is attributed to inadequate resources for making frequent workplace inspections and weak sanctions for standards violations. Contravention of laws respecting child labour, minimum wages, and workplace health and safety is believed to be relatively common.

Counter to Canadian and U.S. union tradition, the majority of Mexican unions are affiliated with the ruling government party and most union leaders tend to be party officials.(55) In addition, workers are rarely allowed to choose their own union; rather the choice is usually made by national labour leaders, government officials, or employers.(56) With the Mexican government exercising control over the labour movement, some are sceptical about whether wages and working conditions will be allowed to improve as a result of NAFTA.(57)

In May 1992, the Canadian government signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Mexico to cooperate on labour standards. The MOU does not set labour standards; it merely provides a framework for mutual cooperation and contacts between labour, industry and government officials.(58) The United States government has signed a similar MOU with the Mexican government.(59) The NAFTA text addresses the labour standards issue in the preamble, which commits the signatories to "improve working conditions and living standards" and to "protect, enhance and enforce basic workers' rights."(60) The NAFTA also states that no country should lower health, safety or environmental standards to attract investment.(61)

Labour groups in Canada and the United States have discussed establishing in the NAFTA a common set of worker rights, such as those in the European Community's Social Charter, but with enforcement of minimum standards.(62) This might guard against the kind of "social dumping" which they foresee arising from a NAFTA where countries purposely kept standards low to encourage investment inflows.

Although business groups do not oppose some mechanism to monitor labour standards, they argue against imposing on Mexico, wage rates and working conditions that match those in Canada and the United States. The BCNI, for example, points out that imposing such conditions would fail to take into account the less developed nature of Mexico's economy and "...would preclude liberalizing trade with more than 100 countries comprising the Third World."(63)

One of the main reasons for President Salinas's decision to negotiate a free trade agreement was to attract foreign investment by locking in Mexico's recent economic reforms. However, Mexico's foreign investment gain does not necessarily translate into investment loss for the United States and Canada. North American free trade may enhance investment opportunities in all three countries(64) and could divert additional investment into the region from outside countries.(65)

It is also uncertain what proportion of Canadian and American plants that set up operations in Mexico might have moved offshore anyway in order to remain competitive with Asian producers. As industry becomes more globalized, corporations are decoupling low-skilled activities from their operations and shifting them to low wage countries.(66) Japanese industry, for example, has maintained its competitiveness despite the Yen's 90% appreciation against the U.S. dollar since 1985 by spinning off to newly industrializing countries those activities involving electronics assembly and some automotive manufacturing. Investment that remains in the North American region is likely to generate more demand for U.S. and Canadian capital goods and other inputs than, say, Pacific Rim investment.

Often, foreign affiliates are established to penetrate the foreign market and typically, they rely on their parent company for components, supplies and technical knowledge. Canadian-owned plants in the United States, for example, tend to import more from their Canadian parents than they export back.(67) In fact, some studies have concluded that foreign investment outflows actually increase domestic production and employment.(68)

Canadian auto parts maker, Magna International's, new $30-million plant located near Mexico City illustrates the type of feedback generated by some foreign investment. The plant was established in order to serve a new Volkswagen assembly plant nearby, not to supply Canadian or U.S. assembly operations, according to Chairman Frank Stronach.(69) However, the company also believes that it will generate business for its other auto parts facilities in Canada. The Mexican operation has purchased steel from Dofasco in Hamilton while the tooling and welding equipment and many of the metal presses also came from Canada.

The presence in Mexico of Canadian companies such as Northern Telecom and Bombardier also appears to be motivated by a desire to penetrate a growing Mexican market, rather than to obtain a cheap production platform from which to export back to Canada or the United States. Such investments would likely be made regardless of whether or not Canada joined the NAFTA.

On the other hand, at least four auto-parts makers have shifted production from Canada to Mexico over the last several years.(70) This is particularly worrisome because the automotive industry forms the core of Canadian manufacturing. However, integration of North American automotive production is already underway. Free trade between the United States and Mexico would hasten the process, bringing additional competitive pressure, particularly on Canadian and U.S. manufacturers of low-technology, labour-intensive auto parts.(71) But Canada's decision to join the negotiations probably did not alter the competitive situation for Canadian automotive manufacturers, since over 98% of automotive imports from Mexico already enter Canada duty-free because of the duty remissions provided by the Auto Pact.(72)

Over 70% of all imports from Mexico now enter Canada duty-free and the average rate of duty on dutiable imports is equal to 10.1%.(73) If low Mexican wages and lax labour and environmental standards were attractive to Canadian firms, this should already be apparent since Canadian import barriers against Mexican goods have already been substantially liberalized.

According to Statistics Canada, the stock of Canadian direct investment in Mexico rose from C$146 million in 1980 to a peak of C$270 million in 1984 before declining to C$175 million in 1990.(74) However, a study by Investment Canada using data from Mexico's National Foreign Investment Commission shows Canadian foreign direct investment in Mexico rising from US$126.9 million in 1980 to over US$400 million in the first 11 months of 1990.(75) Even if the Mexican data were accepted as more accurate, the evidence does not support an exodus of Canadian firms.(76)

Canada's attractiveness as a site for foreign investment may be enhanced by this country's decision to participate in the NAFTA. The alternative would have been a hub-and-spoke trading arrangement where only the U.S. (the hub), through two bilateral agreements, had duty-free access to the markets of the other spokes (Canada and Mexico).(77) As noted earlier, in a hub-and-spoke arrangement firms are likely to prefer locating in the hub country because it offers preferred access to all three countries.

The main concern that Canada and the United States had about the "Europe 1992" program was that the EC was constructing a kind of trade "fortress" to exclude outside countries. Now similar charges may be levelled at the NAFTA.(78)

Like any free trade area or customs union, the NAFTA would have "trade diversion" and "trade creation" effects. Trade diversion occurs when the removal of trade barriers between free trade members makes less efficient (but non-dutiable) production inside the free trade area less costly than efficient (but dutiable) production outside the free trade area. For example, even though suppliers in Europe and elsewhere may be lower cost producers, they may be displaced in, say, the Mexican market by Canadian or U.S. products which enjoy preferential access. Trade diversion provides a gain to producers within the free trade area but it represents a loss for outside countries. Moreover, it provides a less efficient allocation of world resources.

Trade creation occurs when free trade members shift their purchases from higher cost production located inside the domestic market to lower cost foreign producers within the trading bloc. Trade creation benefits producers within the free trade area and improves the allocation of world resources. Without taking into account secondary income effects, the formation of a trading bloc improves world welfare when trade creation exceeds trade diversion effects. Some analyses suggest that trade creation from the EC-92 program outweighed trade diversion between five and ten-fold.(79)

The formation of free trade areas also tends to raise member countries' incomes. This, in turn, increases their demand for imports from countries located inside and outside the trading bloc. For the welfare of outside countries to improve, the income effects must outweigh the trade diversion effects. Analyses suggest that increased EC demand generated by the 1992 program will more than offset trade diversion effects on outside countries. One study found, for example, that Canadian real GDP would eventually rise by about 0.5% due to EC-92.(80)

Any free trade area or customs union must include rules of origin to determine whether goods qualify for the preferential tariff treatment accorded member countries. The EC has been criticized because its rules of origin (for automobiles, semiconductors, electronics and other goods) require foreign companies to undertake locally a certain stage of production or to meet a specific percentage of local content in order to be considered European-origin goods. Outside countries have argued that these rules can restrict international trade flows.

The NAFTA's rules of origin, which are more stringent than those in the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA), may force companies to source more components within the free trade area. For example, automobiles must meet a 62.5% North American content rule, whereas the FTA rule was 50% Canada-U.S. content.

The rules for textiles and apparel have also been made more restrictive. Under the FTA, clothing made from fabrics woven in Canada or the U.S. qualified for duty-free treatment while the NAFTA requires that the yarn (and in some cases the fibre) originate in North America. Canadian suit manufacturers are particularly upset about this rule because they have traditionally used distinctive European and other foreign fabrics to compete in the U.S. market.(81)

For electronic goods, such as teleprinters, telephone switching apparatus, and facsimile machines, there is a requirement that only one of nine printed circuit assemblies (PCAs) may be from outside North America. If the good contains less than three PCAs, all of these must be made in a NAFTA country. In addition, no more than half the semi-conductors used in certain television sets can be from outside North America.

Thus, NAFTA's implications for outside countries will depend not only on the trade diversion and income effects, but on how the Agreement's operating rules interact with those countries' exports. NAFTA's rules of origin are designed to prevent so-called "screwdriver" plants (low value-added facilities) from being established in Mexico as cheap production platforms to export to the rest of North America. However, the very stringency of the rules can raise costs for firms located inside the region. It has been suggested, for example, that rules of origin for textiles may impose so many conditions on producers of, say, Mexican shirts, that "preference for them - and damage to outsiders - is that much less."(82)

In joining the free trade negotiations with the United States and Mexico, Canada is protecting its position in the North American trading environment. To have chosen otherwise would have risked losing some of the benefits obtained under the Canada-U.S. FTA. While initially, the overall gains to Canada from the NAFTA will likely be small, the benefits will increase as the Mexican economy expands.

Nevertheless, many are concerned about the impact on Canadian wages and employment of liberalizing trade with a developing country such as Mexico. It should be recognized, however, that Portugal and Spain are being successfully integrated into the EC, despite the wide disparity between their incomes and those of countries like Germany and France.(83) This has been accomplished without a large migration of firms and without lowering wages in the high-income countries.(84) Moreover, Canadian import barriers against Mexican goods have already been substantially liberalized without significant overall loss of employment or investment. The NAFTA may increase the pressure on U.S. and Canadian low-skilled workers, however, and reinforce the need for governments to emphasize worker training and adjustment.

Labour groups and environmentalists deserve credit for raising concerns about Mexico's labour and environmental standards. Mexico's enforcement in these areas has already improved, largely due to the attention these issues received during the NAFTA negotiations. Though some argue that still more needs to be done to protect workers and the environment, there is nothing preventing the negotiation of further side agreements, as President Bill Clinton has suggested. Furthermore, as Mexico's income increases, driven in part by free trade, more resources will be available to ensure that labour and environmental standards are enforced.

On the other hand, protectionists have exploited labour and environmental issues in order to reach the radical conclusion that all three countries will be worse off from free trade. Certainly, there is no sign that Mexico's workers would be better protected without an agreement or that the environment would receive more attention. Moreover, cancelling the NAFTA might well postpone Mexico's plans to improve its protection in these areas.

The external impact of the NAFTA will depend partially on how the new rules of origin affect outside countries' trade with North America. However, some of the same concerns were expressed about Europe 1992 and most analyses now suggest that initial fears about a "Fortress Europe" were not realized; trade is expected to increase both inside and outside the Community. Trade liberalization, even on a regional scale, tends to raise the incomes of participants, which generates more trade with outside countries. There is no reason to expect that the NAFTA would unfold in a dramatically different fashion.

Canada, Department of Finance. The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment From a Canadian Perspective. Ottawa, November 1992.

Canada, NAFTA Environmental Review Committee. North American Free Trade Agreement: Canadian Environmental Review. Government of Canada, Ottawa, October 1992.

Canada. North American Free Trade Agreement. Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1992.

Canada. North American Free Trade Agreement: An Overview and Description. Supply and Services, Ottawa, August 1992.

De Boer, Elizabeth C. et al. "The Social Charter Implications of the NAFTA." Canada-U.S. Outlook, Vol. 3, No. 3, National Planning Association, August 1992.

Globerman, Steven. Continental Accord: North American Economic Integration. The Fraser Institute, Vancouver, 1991.

Hart, Michael. A North American Free Trade Agreement, The Strategic Implications for Canada. Centre for Trade Policy and Law, Ottawa; Institute for Research on Public Policy, Halifax, 1990.

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde and Jeffrey J. Schott. North American Free Trade: Issues and Recommendations. Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C., 1992.

Husband, David et al. The Opportunities and Challenges of North American Free Trade: A Canadian Perspective. Working paper No. 7. Investment Canada, April 1991.

Industry, Science and Technology Canada. North American Trade Liberalization: Sector Impact Analysis. Ottawa, September 1990.

Lich, Glen E. and Joseph A. McKinney ed. Region North America. Baylor University, Texas, 1990.

Lustig, Nora et al. ed. North American Free Trade: Assessing the Impact. The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C., 1992.

OECD Secretariat. OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris, 1992.

Randall, Stephen J., et al. ed. North America Without Borders? Integrating Canada, the United States, and Mexico. University of Calgary Press, Calgary Alberta, 1992.

Reynolds, Clark W., Leonard Waverman, and Gerardo Bueno, ed. The Dynamics of North American Trade and Investment. Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1991.

U.S. Congress, Congressional Research Service. North American Free Trade Agreement: Issues for Congress. Library of Congress, Washington D.C., Updated 12 July 1991.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. U.S.-Mexico Trade: Pulling Together or Pulling Apart? ITE-545, U.S. Printing Office, Washington D.C., October 1992

U.S. International Trade Commission, Economy-Wide Modelling of the Economic Implications of a FTA with Mexico and a NAFTA with Canada and Mexico, USITC Publication 2516, Washington D.C., May 1992.

Wannacott, Ronald J. U.S. Hub and Spoke Bilaterals and the Multilateral Trading System. C.D. Howe Institute, Toronto, 23 October 1990.

Watson, William G. North American Free Trade Area. Policy Forum Series - 24. John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy, Queen's University, Kingston, October 1991.

Weintraub, Sidney. A Marriage of Convenience: Relations Between Mexico and the United States. Oxford University Press, New York, 1990.

THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE NAFTA

A. Tariffs

Most tariffs on Canada-Mexico trade will be eliminated by the end of a ten-year phase-in period starting on 1 January 1994. Mexico will phase-out its tariffs on corn and dried lentils over a 15-year period. The tariff phase-out on Canada-U.S. trade continues according to the FTA's 10-year schedule.

B. Rules of origin

To qualify for preferential tariff treatment, goods must be wholly made in North America or, if incorporating imported inputs, have undergone sufficient transformation to qualify under a specific tariff classification. Some items, such as automotive goods, textiles and electronic goods must meet special North American content rules.

C. Investment

The NAFTA employs the principles of national treatment and most-favoured nation treatment to investments by other-party investors.

Investment Canada review thresholds for investments by NAFTA investors are the same as under the FTA.

A separate settlement procedure is added for investment disputes.

D. Services

The principles of national treatment and most-favoured nation treatment are applied to cross-border trade in services.

Specifically excluded from the services chapter are social services provided by governments, basic telecommunications, most maritime and air services.

E. Financial services

The principles of national treatment, most-favoured nation treatment, transparency and right of establishment, are established for trade in financial services.

Sale of financial services across borders is permitted.

Canadian foreign ownership restrictions on federally regulated financial institutions are removed from Mexican investors.

Canadian and U.S. financial institutions will be permitted to establish in Mexico subject to market share restrictions until the year 2000.

F. Government Procurement

Procurements by specified government departments and agencies of goods and services over US$50,000, and construction services over US$6.5 million, are opened up to competition from other NAFTA countries.

The respective review thresholds for purchases by government-owned enterprises are US$250,000 for goods and services and US$8 million for construction services.

For procurements covered by the FTA, the dollar thresholds will continue to apply.

G. Land Transportation

The NAFTA provides for the phase-out of barriers to the provision of land transportation services between the NAFTA countries. This includes: bus and trucking services and port services. Rail services remain open to competition.

H. Telecommunications

The NAFTA removes barriers to access for enhanced telecommunications services (but not basic services) by applying the principles of transparency and non-discrimination.

The NAFTA limits the types of standards-related measures that can be imposed on the attachment of telecommunications equipment to public networks.

I. Agriculture

Quotas essential to the maintenance of Canada's supply management system for dairy, poultry and eggs are retained.

Import licences in sectors of Canada-Mexico trade will be replaced with tariffs or tariff-rate quotas.

Canadian import restrictions covering wheat, barley, beef and veal, and margarine will be removed immediately.

J. Review of Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Matters

The NAFTA retains the FTA's dispute settlement provisions in antidumping and countervailing duty matters involving binding decisions by panels.

A special committee may be established upon request to determine whether a country's law has interfered with the panel's decision-making.

K. Institutional Arrangement and Dispute Settlement Procedures

The Trade Commission, the NAFTA's central institution comprised of international trade ministers from each country, is to meet annually.

A Secretariat will be established to serve the Commission as well as other subsidiary bodies and dispute settlement panels.

Disputes regarding the interpretation or application of the Agreement go first to consultation, then to the Trade Commission, then to a dispute settlement panel.

L. Automotive Trade

Canada and Mexico will eliminate mutual tariffs: on automobiles by 50% immediately and the remainder over 10 years; on light trucks by 50% immediately and the remainder over five years; on other vehicles over ten years.

Passenger automobiles, light trucks and engines and transmissions for these vehicles must eventually meet a 62.5% North American content level based on the net cost formula; other vehicles must meet a 60% content level.

M. Textiles and Apparel

Most textile or apparel products must be made from yarn that is North American-made; Cotton and man-made fibre yarns must be made from fibres that are made in North America.

Under tariff-rate quotas (TRQs), yarns, fabric and apparel that do not meet the rules of origin can still qualify for preferential tariff treatment up to specified import levels.

N. Energy and Basic Petrochemicals

The FTA's proportional sharing requirement is retained on Canada-U.S. trade but this provision does not apply to trade with Mexico.

Mexico opens non-basic petrochemicals and electricity-generating facilities to private investment; investment in Mexico's other energy and basic petrochemicals industries remain reserved to the state.

O. Other measures

Disciplines are imposed on the development, adoption and enforcement of sanitary and phytosanitary measures.

Disciplines are set out on the use of technical standards.

Rules and procedures are established for taking "safeguard" actions to provide temporary relief to domestic industries adversely affected by import surges.

Disciplines are established on anticompetitive government and private sector business practices.

The NAFTA requires each country to protect intellectual property rights.

Provision is made for temporary entry of business persons.

As established by the FTA, Canadian cultural industries remain exempt but the U.S. also retains the right to take measures of equivalent commercial effect.

Other countries or groups of countries may be admitted into the Agreement if the NAFTA countries agree.

Any country may withdraw from the Agreement on six-months' notice.

(1) The European Community had a population of 329 million in 1991 and a GDP of C$6,682 billion. If the EC joins with the European Free Trade Association (minus Switzerland) to form the European Economic Area, the combination will have a population of 355 million and GDP of C$7,415 billion.

(2) International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics, Yearbook 1992, IMF, Washington, D.C., 1992.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Statistics Canada, International Trade Division.

(5) Statistics Canada, Canada's International Transactions in Services, 1990 and 1991, Cat. No. 67-203.

(6) Statistics Canada, Canada's International Investment Position, 1991, Cat. No. 67-202.

(7) Based on a Department of Commerce estimate for 1989 cited in Lenore Sek, North American Free Trade Agreement, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C., 3 March 1992, p. 4.

(8) Ibid., p. 5.

(9) Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, North American Free Trade: Issues and Recommendations, Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C., 1992, p. 96.

(10) Ronald J. Wonnacott, U.S. Hub-and-Spoke Bilaterals and the Multilateral Trading System, C.D. Howe Institute, Toronto, 23 October 1990.

(11) Note that whether or not Canada joins the negotiations, some Canadian goods may be displaced once Mexico also enjoys preferential access to the U.S. market.

(12) Portugal and Spain each achieved growth rates averaging 4.2% between 1986 and 1991. This compares with an average (unweighted) growth rate for the G-7 countries of 2.9% over this period. (OECD Economic Outlook, 51, OECD, Paris, June 1992).

(13) Lorraine Eden and Maureen Appel Molot, "The View from the Spokes: Canada and Mexico Face the United States," in Stephen J. Randall et al., ed., North America Without Borders? Integrating Canada, the United States and Mexico, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1992, p. 76.

(14) In 1985 Mexico unilaterally lowered levels of import protection and applied for membership in the GATT; it was accepted as a full member the following year. Subsequent tariff reductions have lowered Mexico's maximum duty rates to 20% from a previous high of 100%. On a trade-weighted basis the country's average tariff is now about 10%, which is comparable to the Canadian rate. The number of goods requiring import licences has gone from virtually complete coverage, prior to the 1985 liberalization, to about 200 product categories at the end of 1991, or less than 6% of Mexican tariff categories. Monetary restraint has reduced inflation from over 160% in 1987 to below 12% in 1992. Fiscal austerity lowered the public sector deficit from almost 17% of GDP in 1982 to 1.5% in 1991. Restrictions on foreign investment have been liberalized and a number of state-owned companies have been privatized.

(15) Recently, the American Economic Review published the results of a survey in which 1,350 U.S. economists were polled on a number of economic propositions. One proposition was that "Tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general economic welfare." The responses were as follows: 71.3% of those polled generally agreed with the proposition; 21.3% agreed with provisos; 6.5% generally disagreed. (Richard M. Alston et al., "Is There a Consensus Among Economists in the 1990's?" AER, Vol. 82 No. 2, May 1992, p. 203.)

(16) Canada, Department of Finance, The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment From a Canadian Perspective, Ottawa, November 1992, p. 26.

(17) See: Drusilla K. Brown, "The Impact of a North American Free Trade Area: Applied General Equilibrium Models" in Nora Lusting et al., North American Free Trade: Assessing the Impact, The Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., 1992, p. 55-56. Similarly, some suggest that the official EC assessment of the gains from European integration (4.3%-6.4% of GDP) is an underestimate. Professor Baldwin of Columbia University estimates that dynamic gains will raise the EC annual growth rate by 0.2%-0.9%, for a total of 11%-35% GDP growth.

(18) Change as a percentage of GDP.

(19) Based on 1989 average hourly manufacturing wages in Canada and Mexico; Canada, Department of Finance, The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment From a Canadian Perspective, Ottawa, November 1992.

(20) Business Council on National Issues, The North American Free Trade Agreement: Why It Is in Canada's Interest, Submission to the Subcommittee on International Trade of the House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Ottawa, 26 November 1992, p. 12.

(21) Canada, Department of Finance, The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment From a Canadian Perspective, Ottawa, November 1992, p. 30. Note that this is the average difference in productivity between the two countries. The productivity gap between specific industries would be smaller in some cases and larger in others.

(22) Ibid.

(23) According to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, lowering the price of a good (whether by removing import protection or by other means) should reduce the return to the factor (either capital or labour) used most intensively in its production. If Canadian tariffs protect labour-intensive production more than capital-intensive production, freer trade should lower the price of labour-intensive goods and reduce labour's return, or wage rate. On the other hand, some studies indicate that the Canadian tariff protects capital more than labour.

(24) United States International Trade Commission, Economy-Wide Modelling of the Economic Implications of a FTA with Mexico and a NAFTA with Canada and Mexico, USITC Publication 2516, Washington, D.C., May 1992, p. 14.

(25) Ibid.

(26) Ibid.

(27) Richard Harris, "The Productivity GAP: Threat or Opportunity? A Modeller's View of the NAFTA," in William G. Watson, North American Free Trade Area, Policy Forum Series - 24, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy, Kingston, Ontario, October 1991, p. 21.

(28) Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, North American Free Trade: Issues and Recommendations, Institute for International Economics, Washington, 1992, p. 136-137.

(29) Ronald E. Pattis, "Enforcement and Resources," Twin Plant News, October 1992, p. 51.

(30) Ibid.

(31) Canada, NAFTA Environmental Review Committee, North American Free Trade Agreement: Canadian Environmental Review, Government of Canada, Ottawa, October 1992, p. 90.

(32) Office of the United States Trade Representative, Review of U.S.-Mexico Environmental Issues, Washington D.C., 25 February 1992, p. 171.

(33) Canada, NAFTA Environmental Review Committee (October 1992), p. 63.

(34) Gene M. Grossman and Alan B. Kreuger, Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement, Discussion Paper #158, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University, Revised- February 1992, p. 35-36.

(35) This implies that, although Mexico may still be "getting dirtier," it is approaching the turning point since its GDP per capita was US$3,484 in 1991.

(36) Canada, North American Free Trade Agreement, Part I, Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1992, (Preamble).

(37) Ibid., Article 104.

(38) Ibid., Article 712, Article 904.

(39) Ibid., Article 713, Article 905.

(40) Ibid., Article 906.

(41) Ibid., Article 1114.

(42) Ibid., Article 2005.

(43) Ibid., Article 2015.

(44) Ibid., Article 914.

(45) David S. Cloud, "Warning Bells on NAFTA Sound for Clinton," The Congressional Quarterly, 28 November 1992, p. 3712.

(46) House of Commons, Sub-Committee on International Trade of the Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, Third Session of the Thirty-fourth Parliament, 24 November 1992, 15:6-12.

(47) NAFTA Environmental Review Committee, North American Free Trade Agreement: Canadian Environmental Review, Ottawa, October 1992, p. 117.

(48) Ibid., p. 94.

(49) Congressman Gephart's proposal for a "cross-border transaction tax" has not yet been introduced as legislation. Congressman Matsui's bill (H.R. 6137) for a uniform fee on imports to be applied by each of the NAFTA signatories was introduced on 5 October 1992 but would need to be re-introduced in the new Congress.

(50) Bill S. 1965, introduced by Senator Slade Gorton on 14 November 1991, would impose an import fee on any goods manufactured using a process that did not comply with U.S. standards under the Clean Water Act. Bill S. 984, introduced by Senator David L. Boren on 25 October 1991, would redefine a countervailable subsidy to include the benefit derived from lax pollution controls. Again, both these bills would have to be re-introduced if their sponsors still wish them to pass.

(51) David S. Cloud, "Warning Bells on NAFTA for Clinton," The Congressional Quarterly, 28 November 1992, p. 3710-3711.

(52) The proposal was made informally during an interview with the Wall Street Journal. See: Matt Mofett and Dianna Solis, "Mexico Will Ask U.S., Canada for Aid to Smooth its Entry to Free Trade Pact," The Wall Street Journal, 8 December 1992.

(53) Drew Fagan, "Mexico's Aid Request Denied: Ottawa Refuses Financial Support for NAFTA Partner," Globe and Mail (Toronto), 9 December 1992.

(54) For a summary of each country's legislation, see: Canada, Labour Canada, Comparison of Labour Legislation of General Application in Canada, the United States and Mexico, Ottawa, March 1991.

(55) Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, North American Free Trade: Issues and Recommendations, Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C., 1992, p. 125.

(56) U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, U.S.-Mexico Trade: Pulling Together or Pulling Apart?, ITE-545, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., October 1992, p. 80.

(57) See for example: Sheldon Friedman, "NAFTA as Social Dumping," Challenge, September-October 1992.

(58) Government of Canada, North American Free Trade Agreement: The NAFTA Partnership, August 1992.

(59) United States. President, Response of the Administration to Issues Raised in Connection with the Negotiation of a North American Free Trade Agreement, transmitted to the Congress by the President on 1 May 1991.

(60) Government of Canada, North American Free Trade Agreement, Part I, Supply and Services, Ottawa, 1992.

(61) Ibid., Article 1114.

(62) Andrew Jackson, "A Social Charter and the NAFTA: A Labour Perspective," in William G. Watson, North American Free Trade Area, Policy Forum Series - 24, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy, Kingston, Ontario, October 1991, p. 77-93.

(63) Business Council on National Issues, The North American Free Trade Agreement: Why It Is in Canada's Interest, Submission to the Subcommittee on International Trade of the House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, Ottawa, 26 November 1992, p. 15.

(64) A survey published in Site Selection magazine would tend to support this idea, as far as U.S. firms are concerned. The survey of U.S. corporate real estate executives working for companies with international operations indicated that 23% of the firms responding would react to a NAFTA by either locating new facilities or consolidating existing facilities over a five-year period. However, almost two-thirds (62%) of these new or consolidated investments would be located in the United States. (Jack Lyne, "U.S.-Mexico Free Trade: Numerous New Facilities Likely- and More U.S. Jobs," Site Selection, October 1991).

(65) A survey of Japanese companies operating in the U.S. revealed that almost one quarter (23.8%) agree that the NAFTA would necessitate changes in their investment strategies. "Of those in agreement, 84.4% said they would consider Mexico as an investment site, compared with 32.8% for the U.S. and 15.6% for Canada." (The Nihon Keizai Shimbun, "NAFTA Impacting Investment Strategy," Nikkei Weekly, 26 October 1992.)

(66) David Husband et al., The Opportunities and Challenges of North American Free Trade: A Canadian Perspective, Working paper number 7, Investment Canada, April 1991, p. 53.

(67) One study found that (between 1981-1984) Canadian affiliates operating in the United States purchased from their parent groups in Canada approximately five times the level of sales that the affiliates sold to their parent groups, averaging a US$4 billion deficit from the U.S. perspective. (Alan Rugman, Multinationals and Canada-United States Trade, University of South Carolina Press, 1990, p. 68.)

(68) For a summary of evidence of the effect of direct investment abroad on domestic production and employment, see: William T. Dickens, "The Effects of Trade on Employment: Techniques and Evidence," in Laura D'Andrea Tyson et al. ed., The Dynamics of Trade and Employment, Ballinger Publishing Company, Cambridge, Mass., 1988, p. 66-85.

(69) John Heinzl, "Magna Chief Close to a Deal to Make Auto Parts in Mexico," the Globe and Mail, (Toronto), 11 June 1991, p. B1.

(70) Auto-parts maker Sheller-Globe Corp. is reported to have shifted production to Monterrey, Mexico at the cost of 400 jobs in Kingsville, Ontario; United Technologies Automotive has moved 319 auto-parts manufacturing jobs from St. Thomas, Ontario, to several locations in the U.S. and Mexico; Fleck Manufacturing Inc. shifted 232 auto-parts jobs to Nogales, Mexico, although the company has since transferred 75 jobs back to Tillsonburg, Ontario, because of quality control problems in Mexico; and TRW Vehicle Safety Systems is moving its seat belt manufacturing operation, involving 194 jobs, to Mexico from Penetanguishene, Ontario. (See: Ann Walmsely, "Turning the Tide," Report on Business Magazine, June 1992, p. 20 and "Penetang Seat-Belt Plant to Move 194 Jobs to Mexico," the Toronto Star, 2 October 1992.

(71) For an evaluation of the competitiveness of Mexico's automotive industry, see: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, U.S.-Mexico Trade: Pulling Together or Pulling Apart?, ITE-545 U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, October 1992, p. 133-150.

(72) Industry Science and Technology Canada, North American Trade Liberalization: Sector Impact Analysis, Ottawa, September 1990, p. 7.

(73) Department of Finance, The North American Free Trade Agreement: An Economic Assessment from a Canadian Perspective, p. 25.

(74) Statistics Canada, Canada's International Investment Position, Cat. No. 67-202, 1988-90, 1991.

(75) David Husband et al., The Opportunities and Challenges of North American Free Trade: A Canadian Perspective, Working paper number 7, Investment Canada, Ottawa, April, 1991, p. 36.

(76) Economist Lester Thurow believes that Canadians and Americans have grossly underestimated the number of companies that will move to Mexico because of lower wages. However, Mr. Thurow attributes this expected shift not to the NAFTA, but to the "collapse of the socialist idea in Mexico." Repudiating the Agreement would not make any difference, according to Mr. Thurow. (Bruce Little, "Lester Thurow on Why Companies Move to Mexico," Globe and Mail (Toronto), 15 January 1993.)

(77) See: Ronald J. Wonnacott, U.S. Hub-and-Spoke Bilaterals and the Multilateral Trading System, C.D. Howe Institute, Toronto, 23 October 1990.

(78) The European Parliament has decided to examine the NAFTA more closely to determine whether it will restrict world trade. "NAFTA under Fire", Globe and Mail (Toronto), 16 December 1992.

(79) Rosemary P. Piper and Alan Reynolds, "Lessons from the European Experience," in Steven Globerman ed., Continental Accord: North American Economic Integration, The Fraser Institute, Vancouver, 1991, p. 142.

(80) Peter Pauly, "Europe 1992: Macroeconomic Implications for the World Economy," in Europe 1992 and the Implications for Canada, John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy, Kingston, Ontario, November 1990, p. 74.

(81) Although the NAFTA has raised the cloth quota for apparel imports made from outside fabrics, Canadian suit makers do not believe that it will be adequate to meet the growth in the U.S. market.

(82) Susumu Awanohara, "Not-So-Fine Print: Nafta's Details May Exclude Asian Traders," Far Eastern Economic Review, 24 September 1992, p. 106.

(83) The relative size of the income disparity is a matter of debate. In 1985, the year before joining the EC, Portugal had a GDP per capita of US$2,089 while West Germany's was US$10,151 or 4.9 times Portugal's. In 1991 the United States had a GDP per capita of US$22,448 or 6.4 times Mexico's GDP per capita of US$3,484.

(84) Joseph McKinney, "Lessons from the Western European Experience for North American Integration" in Stephen J. Randall et al., North America Without Borders? Integrating Canada, the United States and Mexico, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1992, p. 35-36.