|

BP-340E

HEALTH CARE FINANCING:

Prepared by Odette Madore TABLE

OF CONTENTS THE PROS AND CONS OF USER CHARGES IMPOSITION

OF USER CHARGES IN CANADA AND PUBLIC

AND PRIVATE FUNDING OF HEALTH

HEALTH CARE FINANCING: Canadian health care costs are continuing to rise and to represent an increasing percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Health sector expenditures, which totalled $2.1 billion in 1960, rose to $66.8 billion in 1991, while the proportion of GDP devoted to health care almost doubled, going from 5.4% to 9.9% over the same period.(1) This rapid growth in costs is likely to continue, especially with the pressures of an aging population and the adoption of new medical technologies. Because health care services are largely government funded, expenditure control in the health sector is a major public finance challenge, particularly in the present climate of budgetary constraint. Due to the relative scarcity of public resources, governments are more and more wondering whether to increase user participation in financing health care by imposing user charges. Opinions differ, however, as to the potential impact of such increased user participation. While some maintain that user fees will make it possible to limit public health sector expenditures, others fear that such charges would raise barriers to universal access to health care. This paper provides a summary of the current situation with respect to health care user fees. In the first section, we briefly define different types of user fees, while in the second section we outline the theoretical arguments for and against their use. The third section describes the experience of Canada and other OECD countries and summarizes studies that have attempted to assess the results of imposing user fees. Finally, in the fourth and final section, the sharing of health costs between the public and private sectors is examined, as is the opportunity for increasing private sector participation by means of user fees. "User fees" are the share of costs a patient pays for medical and hospital services covered by public health insurance plans. As specified below, there are several different types of such charges. Co-insurance is the simplest form of user charge. Under this system, the patient is required to pay a fixed percentage (say 5%) of the cost of services received. Thus, the higher the cost of the service, the larger the fee. Major users are at a disadvantage, as they must contribute a higher amount than other patients. Co-payment is an alternative to co-insurance. Under this system, instead of having to pay a share of costs, the patient is required to pay a flat fee per service (for example, $5) which does not necessarily bear any relation to the cost of the service. The same amount is charged, no matter what the cost of the health care provided. More intensive use (more services) naturally leads to a higher total payment. A system of deductible amounts requires the patient to pay the total cost of services received over a given period up to a certain ceiling, which is the deductible amount. Above this ceiling, costs of services to the patient are covered by the public health insurance plan. All users must pay a standard minimum deductible amount, which is independent of the quantity of services received. This type of plan places heavy users of the health care system at less of a disadvantage than the other plans. These three types of user charges are usually described as "sickness taxes," because only health care recipients are required to pay them. Since low income groups generally use health care services more than others, user charges are frequently viewed as a regressive tax which hurts those least able to afford it. Extra-billing may also be considered a type of user charge. In this instance, however, the patient's private contribution does not cover part of the costs of insured services, but rather pays costs not covered by the public plan. In such a system, the doctor providing the service can bill the patient for an extra fee over and above the established government rate. All patients requiring medical services are affected, no matter what their income. In the case of an income tax on services, the patient does not pay directly for a share of the cost of insured services received; rather, the contribution is paid through the income tax system. An income tax on services takes both income and use of services into account. The tax rate applies to the sum of taxable income and the cost of services used. This type of charge is one of the options being considered by the Government of Quebec.(2) It is a progressive tax in that, for equal use of services, a patient with a higher income pays relatively more than one with a lower income. Furthermore, an income tax on services does not apply to those who do not pay income tax. De-insurance is an extreme form of user charge whereby the government decides to reduce the range or the extent of services insured. De-insurance may apply to a particular service, such as cosmetic surgery, or may affect only certain groups of individuals, for example those in a high income bracket. Patients using the services no longer covered by the public health insurance system are obliged to pay the entire cost. THE PROS AND CONS OF USER CHARGES The imposition of user charges is put forward as a theoretical means of reducing the use of services and limiting public expenditures in the health sector; however, the issue is very controversial. Opinion is divided as to the true impact of such charges on the rate of use and on costs.(3) Those who maintain that user charges would reduce public expenditures on health services base their argument on traditional demand theory, according to which the consumer who faces a price increase will reduce the quantity of the good or service demanded. The size of the reduction is a function of the price elasticity of demand: the more sensitive the consumer is to price, the more the quantity demanded declines. According to the proponents of this view, user charges limit the use of health services and lead to a decline in public expenditures. The opponents of user charges maintain, on the other hand, that the demand for health services is relatively inelastic; that it is not dependent on price as much as on necessity. According to this view, if patients are not very sensitive to pricing, user fees will not necessarily reduce the use of health services; even if public expenditures on health services decline because they are partially replaced by user charge revenues, total combined public and private expenditures are liable to increase. The impact of user charges on total health expenditures is difficult to measure, however, as it is dependent on the amount of the fees charged. Other opponents of user charges observe that, while the demand for health services is generally inelastic, price sensitivity varies according to patient income. Thus, user fees act as a regressive tax in that they discourage low income individuals from using the health system to obtain needed services. It is recognized, however, that any delay in seeking necessary medical care substantially increases the ultimate cost of services. A patient who does not consult a doctor when symptoms first appear is liable to increase the severity of his or her illness, to have to undergo longer and more costly treatment, and to have a reduced probability of a complete cure. Proponents of charges believe that a free health care system leads patients to overuse or even abuse it. According to this view, user charges automatically lead to more efficient use of health services, with a resulting decrease in health costs. Opponents of charges, on the other hand, question whether there can be abuse or inappropriate use of health care services when patients have little decision-making power in this respect. This is particularly so in the case of hospital services, which the doctor, rather than the patient, decides whether or not to use. For this reason, their opponents believe that user charges will have little impact on use of the system or on health care costs. Other arguments are also advanced to show that user charges do not limit health care expenditures. First, some suggest that doctors might begin to expand their activities in response to declining numbers of patients; proponents of this view argue that the fee-for-service method of payment to doctors tends to encourage such behaviour. Second, there are those who note that imposing user charges has a negligible impact because of a "rebound effect," whereby one service is substituted for another. For example, if user charges are imposed for doctors' services, patients may have an incentive to go to hospitals (particularly emergency services) rather than going to a doctor and paying an additional direct fee. Third, some maintain that user charges incur high administration costs, which could easily exceed any savings to governments. Fourth, some believe that if a high percentage of the population has to pay a substantial amount in user fees, consumers will seek to protect themselves against the financial risk of illness and resort increasingly to private insurance. A system in which private insurance predominates, as is the case in the United States, does not guarantee effective control of health care costs. Finally, some opponents of health care user charges find the very idea of imposing them incompatible with basic health insurance principles; they believe they are liable to lead to the dismantling of Canada's free and universal nationwide health care system. These critics often refer to equity. They maintain that direct charges prevent those who are most disadvantaged from consulting a doctor, and discourage them from following medical advice. Yet, according to various sources, it is these very disadvantaged groups who are in the greatest need of health care. The critics also maintain that if user charges were imposed, the poor, the elderly and the very ill -- those least likely to be covered by supplementary insurance -- would be forced to spend a higher proportion of their income on health care than the rest of the population. The proponents of charges argue, however, that the regressivity of user charges could be balanced by exemptions for disadvantaged groups. IMPOSITION

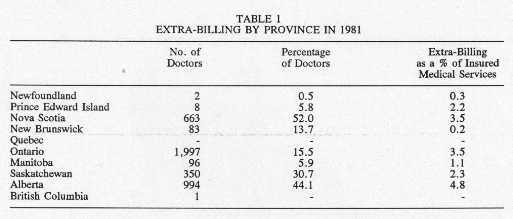

OF USER CHARGES IN CANADA AND In the early 1980s, most provincial governments in Canada authorized extra-billing and imposed user fees of one sort or another. In most provinces, doctors extra-billed their patients directly, though the extent of this practice varied a good deal by province. Table 1 shows that in 1981 over half of all doctors in Nova Scotia charged additional fees, whereas only one doctor in British Columbia did so. While the revenues from extra-billing were relatively minor in Newfoundland and New Brunswick, they represented almost 5% of the total value of medical services in Alberta.

Source: National Council of Welfare, Medicare: The Public Good and Private Practice, May 1982, Annex B. Governments in some provinces also imposed user charges for patients receiving insured hospital services. Once again, fee levels varied greatly from one province to another. As shown in the data for 1982,(4) British Columbia and Newfoundland charged patients in general hospitals a daily co-payment of $7.50 and $3 respectively, whereas in Alberta patients were required to pay a $5 hospital admission fee. In 1982, four provinces imposed daily fees for long-term chronic care hospital patients. These fees were: British Columbia, $11.50; Alberta, $7.00; Ontario, $12.60; and Quebec, $12.33. British Columbia hospitals also charged a co-payment of $4 for each emergency service visit, and $7 for outpatient surgery. The provinces that imposed co-payment charges for hospital costs offered exemptions for certain groups, such as welfare recipients, the elderly and children. Only one province, Saskatchewan, imposed co-payment for doctors' services. Between 1968 and 1971, patients in this province paid $1.50 per doctor's office visit, and $2 per house call. The 1984 Canada Health Act ended the authorization of user charges and extra-billing. The federal government's justification for this initiative was based on studies evaluating the impact of the various formulae for user charges.(5) These analyses indicated that user charges for insured medical and hospital services reduce use of the system by low-income earners, and in fact act as a regressive tax. The results of these studies also showed that user charges do not reduce the overall rate of health care service use, and that they are ineffective in controlling total health care costs.(6)(7) At present, the federal government makes transfer payments to the provinces for "medically necessary services" insured under their respective health insurance plans. These services include the full range of care provided by hospitals, doctors and dental surgeons in institutions. These transfer payments are made on condition that the provinces do not extra-bill or charge user fees. The federal government also makes additional payments for supplementary health services such as intermediate care in nursing homes, adult institutions, or at home. These payments are not subject to any conditions, and such services may therefore be subject to charges. In addition, the provinces may impose user charges for other supplementary services insured under their respective health insurance plans, such as optometry, dental and pharmaceutical services. Some provinces insure 100% of supplementary health service costs, while others impose co-insurance, co-payment or a deductible amount. In their most recent budgets, some provinces decided to de-insure some services. For example,(8) Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island do not insure optometry services, while Ontario covers eye examinations for all residents. The remaining provinces cover eye examinations and prescriptions for certain groups, usually young people and the elderly, and require a financial contribution from recipients of other optometry services, either through a 20% co-insurance fee or a deductible of about $500. Similarly, four provinces (New Brunswick, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia) do not insure children's dental services; the rest of the provinces cover insured services for children, with three requiring a co-payment of between $5 and $25. Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia insure some prescription drugs, but with a deductible and co-insurance fee. Only Ontario covers the full cost of prescription drugs for the elderly; the other provinces insure prescription drugs, but impose user fees from which welfare recipients are usually exempt. While user charges are in limited use in Canada, they are widely used in some OECD countries. France, for example, has a complex user fee system in place. Medical services are subject to a 25% co-insurance fee and some doctor's visits may also be subject to extra-billing. Prescription medicines are subject to co-insurance, which varies from 30 to 60% depending on the product's degree of necessity. Hospital services are also subject to user fees. A co-payment of 55 FF ($12 CDN) a day is required for hospitalization; to this is added a 20% co-insurance fee for hospital stays of less than 30 days. A 30% co-insurance fee is applicable to laboratory tests and dental care. There are exemptions for low income earners and the chronically ill.(9) The Swedish health insurance system covers an extensive range of health services, and also includes a variety of user charges. A co-payment of 55 Crowns ($11 CDN) is required for services provided by a public sector doctor; between 60 and 70 Crowns ($12 to $14 CDN) are paid for services provided by doctors in private practice. Co-payment does not apply to some medical services, such as birth control consultations. Hospital care is virtually free. For dental treatments, there is a user fee of 60% on the first 2,500 Crowns ($480 CDN), and 25% on the balance. A co-payment of 25 Crowns ($5 CDN) is charged for physical, occupational and speech therapy when prescribed by an authorized medical practitioner. In addition, a 30-Crown ($6 CDN) co-payment is charged for transporting a patient. Finally, prescription drugs are subject to a 65-Crown ($13 CDN) co-payment; life-sustaining drugs are free.(10) Charges are also authorized in other countries, but their use is more limited. For example, Germany applies a co-payment system which exempts children and low-income earners. A fee of 2 DM ($1.34 CDN) per person is levied on prescription drugs and hospital patients must pay 5 DM ($3.35 CDN) each day for a stay of up to 14 days, and a fee of 5 DM ($3.35 CDN) for transportation by ambulance.(11) In the United Kingdom, user charges apply only to prescription drugs, and individuals may choose between co-payment, from which certain groups are exempt, and a deductible amount. Patients must pay £3.05 ($7 CDN) for each prescription. Those not eligible for the exemption may opt for a deductible amount of £43.50 ($97 CDN).(12) Studies of user charges in some of these countries draw conclusions similar to the Canadian studies. Analysis has revealed that user fees do not enable governments to control health costs, that they risk leading to under-consumption of medical services by those who are the most ill, and that they are frequently ineffective when patients have supplementary insurance.(13) In addition, in a report published recently, the World Health Organization emphasized that user fees are liable to make a health care system less effective and to jeopardize equality of health care.(14) Furthermore, a Rand Corporation study of the United States found that there was a decrease in the consumption of services when patients are required to pay fees directly. The authors of the study noted that this decrease in consumption affected both essential and non-essential services, that it affected low income individuals most, and that it had undesirable effects on the health of the patients who use the services less frequently. These authors concluded that the existence of user charges has no effect on the total cost of services.(15) In summary, Canadian and foreign studies would appear to show that user fees affect health care equity and do not seem to be the most appropriate solution for resolving the financing problems of health care systems. Although some countries continue to apply a policy of user fees, the problem of financing the health care system remains a major concern for their governments. For instance, a number of them are studying the systems of other countries in their quest to improve the effectiveness of their own systems and to control health care costs. Canada decided less than a decade ago to forgo user fees, but it would appear that there is now a desire to take a step backward. PUBLIC

AND PRIVATE FUNDING OF HEALTH In spite of past experience and the criticisms levelled at user charges, some provincial governments in Canada are currently studying the possibility of increasing private participation as a way of reducing public expenditures on health care. For a number of years, the public has been hearing about "spiralling" health costs and the need for governments to control their expenditures in this sector. Far from being casual remarks, these comments reflect the current reality. Table 2 shows the trend for total health costs over the last three decades. It is true, on the one hand, that health care expenditures have grown continually in real terms, and are consuming an increasing share of our national income. In 1960, health care expenditures totalled $2.1 billion. In 1991, they totalled $66.8 billion, or $183 million per day and $7.6 million per hour! Expressed in constant 1986 dollars, total health care expenditures rose from $8.9 to $54.8 billion over three decades. The substantial real growth of expenditures in the 1960s and early 1970s was due primarily to the establishment of hospital and medical insurance plans by all the provinces in 1961 and 1975 respectively. Subsequently, while total expenditures have continued to rise in real terms, they have done so at a slower pace.

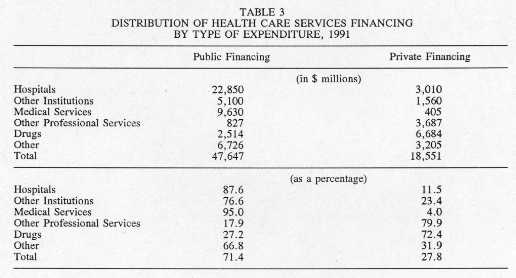

Source: Data obtained from the Health Information Division, Health Policy, Planning and Information Branch, Health and Welfare Canada, Ottawa, April 1993. It is also true that Canada is spending an increasing proportion of GDP on health care. Between 1960 and 1991, the proportion of GDP allocated to health rose from 5.4 to 9.9%. This percentage increased between the 1960s and 1970s, as the universal health insurance plans were introduced, then remained relatively stable until the early 1980s, since when it has increased consistently. Internationally, Canada is among OECD countries spending a large percentage of their economic output on health care. Available data show that in 1990, the percentage of GDP expended on health care was 9.4% in Canada compared to 9.2% in Sweden, 8.8% in France, 8.1% in Germany, and 6.2% in Great Britain.(16) Furthermore, Canada's provincial governments are an important source of financing for the health sector. In 1991, the public sector as a whole (combined federal, provincial and municipal governments) financed 71.4% of total expenditures on health care. Individuals assumed 27.8% of the total cost, either directly when receiving a service, or indirectly through private supplementary insurance plans. As is evident from Table 3, the distribution of funding between the public and private sectors varies considerably by type of service. The public sector covers 87.6% of hospital services and 95% of medical services. This large public contribution reflects the Canada Health Act, under which medically necessary services are universal and free of charge: patients are not required to pay anything when using them. For other services, on the other hand, the public plans offer more limited coverage, and the private sector therefore provides a larger share of the financing. Finally, health sector expenditures are currently the largest provincial government budget item, representing approximately one-third of total expenditures.(17) Furthermore, in recent years health care expenditures have taken up an increasing proportion of provincial budgets.

Source: Health and Welfare Canada, Health Expenditures in Canada - Summary Report, 1987-1991, Health Information Division, Health Planning and Information Branch, Ottawa, March 1993. In sum, total health care expenditures continue to rise in real terms, and are consuming an increasing share of GDP. Furthermore, the proportion of GDP spent on health care is higher in Canada than in other OECD countries. Since governments are the primary source of financing, control of health care expenditures is a major challenge for public finances, particularly in the present context of budgetary restraint. This seems to justify governments' review of the fairness of how health care financing is shared. However, a detailed examination of the distribution of funding will be required prior to any decision on the appropriateness of implementing user fees. Indeed, a study of the changes in amounts paid towards health care by the various financing sectors shows that the public sector's share has decreased in recent years, while the private sector share has steadily increased. As Table 4 illustrates, as a result of the implementation of the national health insurance plan, public sector financing of health care services rose overall from 43% in 1960 to 76% in 1975. Since then, however, the public sector share has declined slowly, reaching 72% in 1991. The federal share rose from approximately 16% in 1960 to almost 33% in 1980. Because of budgetary restraints, however, the federal government has limited the rate of growth of transfer payments to the provinces for health care several times; as a result, the proportion of federal government expenditures was down to 24% in 1991. Provincial government expenditures on health care as a percentage of total expenditures increased rapidly until the mid-1970s, then declined marginally. They have, however, recently begun to increase again, in order partly to counterbalance the decrease in federal funding.

Source: Data supplied by Health Information Division, Health Policy, Planning and Information Branch, Ottawa, March 1993. In the same way, the percentage of health care expenditures financed by the private sector has grown in recent years, to 28% in 1991, a level higher than in the period when extra-billing and user charges were permitted. Although the use of user charges is limited in Canada, the private share of health care costs is larger than in other OECD countries. Furthermore, private financing of health care is higher in Canada than in countries with user charges in effect for a wider range of services. For example, data for 1987 show that the private sector financed 26% of total health sector expenditures in Canada; for the same period, private sector financing was 25% in France and 10% in Sweden.(18) The use and types of user charges vary from one country to another. Overall, in Canada as elsewhere, user fees seem to be common for such services as drugs. However, some countries use charges more extensively than is done in Canada. As we have seen, user charges apply only to supplementary health services in this country, whereas they are imposed for a wide range of services, including medical and hospital services, in other OECD countries. The desire to reduce or to stabilize the deficit is probably responsible in large part for the rebirth of the user fee debate in Canada. Governments must impose budgetary restraint and make difficult choices in all the sectors in which they are involved, including health care. It should not be forgotten, however, that one of the basic objectives of introducing a public health insurance plan in Canada was to eliminate the financial obstacles to obtaining hospital and medical care. At present, the health insurance system permits the financial burden to be distributed fairly between those who are well off and those living in poverty, and those in good health and those who are ill. Various studies suggest that user charges might compromise this principle of equity. The desire to reduce government deficits is acting as a constraint on public financing of health care and how costs are shared between levels of government and between the public and private sectors. Although it appears necessary to contain growth in Canadian health care expenditures, before implementing a user charge policy, governments should consider carefully whether the private sector -- the individual, household or family -- is able to assume a larger share of these costs. Badgley, R.F. and R.D. Smith. User Charges for Health Services. Ontario Committee on Health Services, 1979. Barer, M. L., R.G. Evans and G.L. Stoddart. Controlling Health Care Costs by Direct Charges to Patients: Snare or Delusion? Ontario Economic Council, Occasional Paper No. 10, 1979. Beck, R.G. "The Effects of Co-payments on the Poor." Journal of Human Resources, 1974, p.129 -142. Beck R.G. and J.M. Horne. An Analytical Overview of the Saskatchewan Copayment Experience in the Hospital and Ambulatory Care Settings. Report for the Ontario Committee on Health Services, 1978. Creese, A.L. User Charges for Health Care: a Review of Recent Experience. Division of Strengthening of Health Services, World Health Organization, SHS Paper No. 1, 1990. Government of Canada. Preserving Universal Medicare: a Government of Canada Position Paper. Ottawa, 1983. Government of Quebec. Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Un financement équitable à la mesure de nos moyens. 1991. Government of Quebec. Ministère des Finances et Conseil du Trésor. Les finances publiques du Québec: vivre selon nos moyens. 19 January 1993. Government of Saskatchewan. Report on Utilization Charges. Department of Public Health, 1979. Health and Welfare Canada. Health Expenditures in Canada - Summary Report, 1987 - 1991. Health Information Division, Health Policy, Planning and Information Branch, March 1993. House of Commons, Standing Committee on Health and Welfare, Social Affairs, Seniors and the Status of Women. The Health Care System in Canada and Its Funding: No Easy Solutions. Ottawa, May, 1982. Hurley, J. and N. Arbuthnot Johnson. "The Effects of Co-Payments Within Drug Reimbursement Programs." Policy Options, Vol. 17, December 1991, p. 473 - 489. Majnoni d'Intignano, B. "Financing of Health Service Systems: Recent Developments and Reforms." International Social Security Review, Vol. 44, No. 3, 1991, p. 5 - 21. National Council of Welfare. Medicare: The Public Good and Private Practice. Ottawa, May 1982. OECD. "Health Care Systems in Transition: The Search for Efficiency." Social Policy Studies, No. 7, Paris, 1990. OECD. The Reform of Health Care: a Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries. Paris, 1992. Rochon Commission. Rapport de la Commission d'enquête sur les services de santé et les services sociaux. Government of Quebec, 1988. Stoddart, G.L. and R.J. Labelle. Privatization in the Canadian Health Care System: Assertions, Evidence, Ideology and Options. Health and Welfare Canada, October 1985. The Swedish Institute. "Health and Medical Care in Sweden." Fact Sheets on Sweden. 1990.

(1) Data were provided by the Health Information Division, Policy, Planning and Information Branch, Health and Welfare Canada, April 1993. (2) Quebec, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux, Un financement équitable à la mesure de nos moyens, 1991, p. 78-82. (3) The advantages and disadvantages of increased privatization of health care were discussed extensively in a study by G.L. Stoddart and R.J. Labelle, Privatization in the Canadian Health Care System: Assertions, Evidence, Ideology and Options, Health and Welfare Canada, October 1985. (4) National Council of Welfare, Medicare: The Public Good and Private Practice, May 1982, Annex C. (5) Government of Canada, Preserving Universal Medicare: A Government of Canada Position Paper, Ottawa, 1983. (6) References are as follows: R.F. Badgley and R.D. Smith, User Charges for Health Services, Report of the Ontario Committee on Health Services, 1979; Government of Saskatchewan, Department of Public Health, Report on Utilization Charges, 1979; National Council of Welfare, Medicare: The Public Good and Private Practice, Ottawa, May 1982; R.G. Beck, "The Effects of Copayments on the Poor," Journal of Human Resources, 1974, p. 129-142; R.G. Beck and J.M. Horne, An Analytical Overview of the Saskatchewan Co-payment Experience in the Hospital and Ambulatory Care Settings, Report for the Ontario Committee on Health Services, 1978; M.L Barer, R.G. Evans and G.L. Stoddart, Controlling Health Care Costs by Direct Charges to Patients: Snare or Delusion?, Ontario Economic Council, Occasional Paper 10, 1979. (7) Today, studies of the impact of user charges for drug insurance program beneficiaries are coming to similar conclusions. For a summary of these studies, see J. Hurley and N. Arbuthnot Johnson, "The Effects of Co-Payments Within Drug Reimbursement Programs," Policy Options, Vol. 17, December 1991, p. 473-489. (8) Source of 1992 data: Government of Quebec, Ministère des Finances et Conseil du Trésor, Les finances publiques du Québec: vivre selon nos moyens, Government of Quebec, 19 January 1993, Annex 3. (9) 1991 data. The rate of exchange at 31 December 1991 was: $1 CDN = 4.483FF. OECD, The Reform of Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries, Paris, 1992, p. 47. (10) Data for 1988. The exchange rate at 31 December was: $1 CDN = 5.1622 Crowns. The Swedish Institute, "Health and Medical Care in Sweden," Fact Sheets on Sweden, 1990. (11) Data for 1988. The exchange rate at 31 December 1988 was: $1 CDN = 1.4927 DM. OECD, The Reform of Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries, Paris, 1992, p. 59. (12) Data for 1990. The exchange rate at 31 December 1990 was: $1 CDN = £0.447. OECD, The Reform of Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries, Paris, 1992, p. 115. (13) B. Majnoni d'Intignano, "Financing of Health Service System: Recent Developments and Reforms," International Social Security Review, Vol. 44, No. 3, 1991, p. 5-21. (14) A.L. Creese, User Charges for Health Care: A Review of Recent Experience, Division of Strengthening of Health Services, World Health Organization, SHS Paper No. 1, 1990. (15) See summary in: Rochon Commission, Rapport de la Commission d'enquête sur les services de santé et les services sociaux, Government of Quebec, 1988, p. 653. (16) These data were obtained from the following sources: Canada: Health and Welfare Canada, Health Expenditures in Canada - Summary Report, 1987-1991, March 1993, Table I; Sweden: The Swedish Institute, "Health and Medical Care in Sweden," Fact Sheets on Sweden, 1990, p. 3; France, Germany and the United Kingdom: OECD, The Reform of Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries, Paris, 1992, Table 10.1. (17) House of Commons Standing Committee on Health and Welfare, Social Affairs, Seniors and the Status of Women, The Health Care System and Its Funding: No Easy Solutions, Ottawa, June 1991. (18) OECD, Health Care Systems in Transition: The Search for Efficiency, Social Policy Studies No. 7, Paris, 1990.

|