|

BP-382E

FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL

FISCAL RELATIONS

Prepared by Marion G.

Wrobel TABLE

OF CONTENTS A RE-ALIGNMENT OF TAXING POWERS A.

The Potential Advantages A FEDERAL BAILOUT OF THE PROVINCES A.

The Potential (Dis)Advantages FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL FISCAL

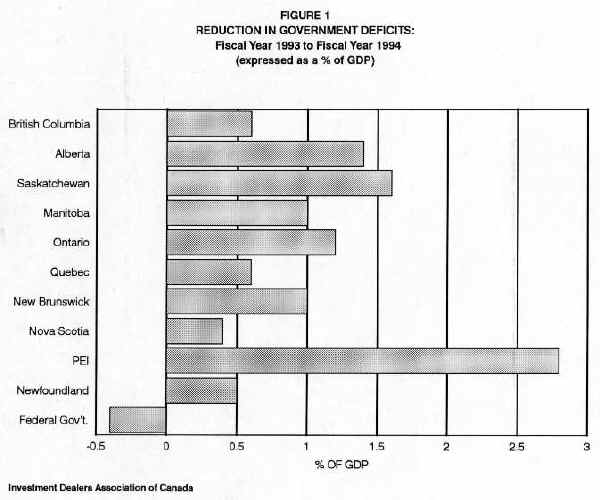

RELATIONS The last round of constitutional discussions led Canadians once again to reconsider the appropriate roles for each of their various levels of government. While the discussion was dominated at that time by the re-allocation of spending and regulatory powers, the appropriate distribution of taxing powers would follow logically from any rearrangement of responsibilities. The division of such powers in Canada has not been static over time, despite the fact that constitutional change has been hard to come by. As economic and political circumstances have changed, and as citizens have increased their demands for publicly provided goods and services, the relative size of the provincial and federal governments has altered. Since World War II, when the federal government received about 80% of all government own-source revenues for example, the relative position of that government has declined, so that it now receives less than one-half of all own-source revenues. Changing economic and fiscal circumstances are today causing some to call for revised federal-provincial economic roles. Current and past fiscal decisions by governments have created problems that require some fiscal realignment. Similarly, present trends indicate that existing arrangements might not be optimal, or even sustainable. This paper is concerned with two recent proposals for restructuring federal-provincial economic roles, each of which is driven by purely economic considerations. Neither proposal would make major changes to the current distribution of spending powers. One would involve simply a re-alignment of taxing powers, while the other would be based upon a large-scale federal loan to the provinces coupled with constraints on transfer reductions and provincial deficit financing. Both of these proposals can be seen as responses to an impending vertical imbalance in the resources available to these two levels of government. One way of defining structural imbalance for any level of government is to determine whether the future growth of revenues and expenditures in the existing system (i.e., one with no change in policy) tends towards fiscal balance, growing deficits or growing surpluses. Determining vertical imbalance requires us to look at the structural balance of two different levels of government. If there exists a structural imbalance at the federal level moving in one direction and a structural imbalance at the provincial level moving in the opposite direction, a vertical imbalance exists. Put simply, the term implies an inappropriate allocation of taxing powers in the face of existing spending responsibilities. Such an imbalance is thought to exist in Canada because the provinces are responsible for people-oriented programs (health, education, social services, etc.) with high inherent growth rates, yet they rely for funding upon a set of taxes that cannot grow adequately to fund expenses. The federal government, on the other hand, has at its disposal a set of taxes expected to generate revenues that will grow faster than program spending requirements. These are the conclusions of a series of studies by Ruggeri et al.(1) which offer a solution to what the authors view as vertical imbalance in the fiscal structure of Canada. Such a misallocation of taxing powers can produce a host of negative consequences. Provincial governments faced with growing deficits will have to cut back on necessary programs or raise taxes. The federal government, on the other hand, might be prompted to search for new spending programs in view of its strong and un-needed revenue growth. This could increase the aggregate size of the overall government sector at the same time as it reduced to sub-optimal levels the size of the provincial government sector. The authors see a problem in the fact that this fiscal imbalance, rather than political and economic considerations, might be the driving force behind future spending decisions. Michael Mendelson, a senior bureaucrat in the Ontario government, has also concluded that a structural imbalance exists at the provincial and federal levels, with the imbalance more pronounced at the provincial level. In an October 1993 paper,(2) Mendelson predicted that both the federal and provincial governments will experience stronger pressures to cut program spending on account of debt servicing costs, which will continue to grow, despite strict controls on real program spending. Mendelson is predicting very slow revenue growth (three-quarters the growth of income) in the future. This is in sharp contrast to the estimates of Ruggeri et al., who see total revenues growing faster than output in the future, largely on account of the fecundity of the personal income tax. The debt servicing situation varies enormously by province. It is predicted that interest costs will consume a growing proportion of the revenue of the Ontario and Nova Scotia governments but will fall in other provinces. This problem is, however, greatest for the federal government. A RE-ALIGNMENT OF TAXING POWERS The tax re-alignment proposals of Ruggeri et al. call for the federal government to take exclusive control of sales taxes as well as corporate income and capital taxes. (Currently the provinces are involved in both and are in fact dominant in the sales tax domain.) The provinces, on the other hand, would take exclusive control over the personal income tax field, which both jurisdictions currently inhabit, although the federal government has clear dominance. The personal income tax is so lucrative that such reform would shift more financial resources to the provincial sector in aggregate than are needed to meet program spending demands. Consequently it is proposed that the provinces would return to the federal government about 5% of their personal income tax revenues. Such a re-alignment would still leave the federal government with sufficient resources to finance its own spending programs. The authors believe it would stabilize the ratios of deficit and debt to GDP for both levels of government and would lead to the end of Canada Assistance Plan and Established Programs Financing transfers to provinces from the federal government. The equalization program could also be set up so that the "have" provinces would transfer moneys directly to the "have not" provinces. This proposal would generate more tax and fiscal stability and eliminate vertical fiscal imbalance. The provinces, the jurisdictional level with the greatest demands for growth in program spending, would be given the revenue tools to finance that responsibility. By giving the federal government exclusive jurisdiction for corporate income and capital taxes, provincial tax competition in this area would be eliminated. The corporate tax would be harmonized and simplified, enhancing economic efficiency. Capital is the most mobile factor of production and a single tax would lead to a geographic distribution of capital and production based solely on economic factors, not tax rules. Similarly, a single sales tax would reduce compliance and administration costs and enable federal collection of the tax at the border. All of these items have become controversial since the introduction of the GST on top of the nine existing provincial retail sales taxes. Finally, these proposals would improve the accountability aspect of taxation. By thus eliminating overlap and duplication, Canadians would become more aware of where tax increases originated. If sales tax rates were increased, we would know that this was a federal decision. If personal income taxes were increased, we could blame the relevant provincial government. With the end of federal-provincial transfers, we would be less likely to hear one level of government blaming another level for the fact that it needs to raise taxes. Each level of government would impose taxes to finance its own program spending. Citizens and voters would have a clearer view of the fiscal consequences of any demand for new program spending. These proposals are not without problems. The federal government's complete departure from the personal income tax field, by far the most important tax area in Canada, might lead to a disintegration of the highly harmonized personal income tax system that now exists. This would increase compliance and administration costs and lead to some additional resource misallocation. Although individuals are not as mobile as capital, there are real economic benefits to harmonization which might be lost. Some tax-driven mobility does exist already and could be enhanced under this proposal. With the exception of the proposal for the corporate income tax, the other proposals go against the current public finance wisdom.(3) For example, it is commonly argued that sales taxes are suited to provincial governments because they attempt to tax consumption and result in few cross border movements. (This is notwithstanding what many people believe to be the effects of the GST.) The fewer the mobility effects of a tax, it is said, the lower the level of government that should use it. Yet this proposal would give the federal government exclusive jurisdiction over this domain. The personal income tax is the workhorse of the tax system and is the tax most suited to achieving distributive goals. Since we generally view such goals on a national rather than strictly provincial basis, a strong federal presence is normally held to be desirable. Moreover, federal transfers to persons are increasingly being structured like negative taxes. Conflict and inconsistency in program design might arise if the federal government were to abandon the personal income tax field yet maintain responsibility for most transfers to persons. There is also a more fundamental issue. The existing vertical imbalance is in many respects deliberate and in some ways desirable. It allows the federal government to make transfers to the provinces. These fiscal transfers are used to promote equity and efficiency; they deter some fiscally driven mobility of resources and allow provinces to fund programs that benefit Canadians in other provinces, and could be used to promote the integrity of the internal common market. If no fiscal gap existed, "there would exist NFB [net fiscal benefit] differentials from provincial budgetary activities, and these could be quite large. The differentials would lead to a violation of horizontal equity across the federation – so-called fiscal inequity – and, to the extent that labour was mobile, to an inefficient allocation of labour as well."(4) It is unlikely, in the absence of federal participation, that the provincial governments could produce an equalization system that would sufficiently close this gap in NFBs. A FEDERAL BAILOUT OF THE PROVINCES Mendelson proposes a three-part package of fiscal reforms. In the first place, the federal government would assume a very large part of the existing provincial government debt, anywhere from $100,000 million to $200,000 million. This would be achieved by lending to each province an equal per capita amount over a very long period of time at zero interest. This would be equivalent to annual transfers to the provinces for the purposes of paying much, if not all, of their debt servicing costs. In effect, however, it would be a full or partial bailout of provincial government debt. Such a loan would carry the proviso that it must be repaid in full should a province leave Confederation. The second part of the plan is for a constitutional requirement for provinces to balance their budgets within a short period of time and for future budgets to be balanced on an annual basis. Mendelson does not specify whether this balance would apply to the total or current budget, or some other subset, or how quickly budget balance should be achieved. The third component would be a constitutional amendment to limit severely, if not completely, the ability of the federal government to change transfer payment formulas unilaterally. A. The Potential (Dis)Advantages As a result of their current fiscal problems, the provincial governments currently face enormous difficulties in meeting their spending obligations. Debt servicing costs are consuming ever-increasing amounts of their revenues. Revenue growth has been curtailed by the past recession while demographic and economic demands are putting upward pressure on expenditures. Provincial governments would find it much easier to meet their program demands if they were not burdened by high debt servicing costs. This is, of course, true also of the federal government. The Mendelson plan would not remove the burden of debt; it would merely transfer that burden from one level of government to another. There is a financial advantage to such a transfer, since the federal government enjoys lower borrowing costs than the provincial governments. Thus, through the transfer, the total national resources devoted to interest payments could be reduced and a greater portion of tax revenues could be spent on programs. Mendelson is also concerned with the instability of provincial fiscal capacity. Migration between provinces is common and easy. Large-scale out-migration can erode a province's tax base and greatly exacerbate its debt problems. Two potential candidates for such concerns are Newfoundland and Saskatchewan. Emigration is far less of a problem at the national level, which explains why provincial governments have higher debt servicing costs. By removing high debt servicing costs from the provincial budgets Mendelson thinks such inefficient migration would diminish. This is not completely true. The various provinces would still have differential fiscal capacities. Some would have lower tax rates. Some would have higher benefits. These factors could still encourage fiscally based migration. Furthermore, concern about migrating to avoid one's share of the debt is based on an assumption that the province offers no long-lasting benefits resulting from the policies that created the debt in the first place. Thus deficit spending must have been used for current consumption or to finance private capital accumulation. In these circumstances tendencies towards migration might in fact be a reflection of bad fiscal policies on the part of the respective governments. Provincial governments rely upon external financing much more than the federal government. Provincial governments pay interest to foreigners, whereas the federal government pays interest to Canadians, who subsequently pay taxes in this country at the federal and provincial levels. This is true but irrelevant. Shifting the debt burden to the federal government would do nothing to reduce our external indebtedness. Canadians must borrow abroad because our economy does not generate sufficient savings to meet the needs of the private and government sectors. If the government sector attempted to tap more of the domestic savings market, the private sector would be driven to the foreign market. The liabilities of individual borrowers might change but the situation would remain the same in aggregate. Thus there really would be no reduction in the current account leakage, as Mendelson suggests.(5) The Mendelson proposal is also believed to have an advantage in that it would put all fiscal policy in the hands of the government with ultimate control over monetary policy. In fact Mendelson is able to claim that his proposal would produce declining interest costs over time only because of his inherent assumption of a "more flexible monetary policy" which could "reduce debt servicing costs dramatically."(6) This is potentially a very dangerous proposal as he is coming close to suggesting that part of this debt be monetized. The Mendelson proposal sees as an advantage the fact that only the federal government would be able to engage in economic stabilization, which would make it easier to co-ordinate monetary and fiscal policies. The federal government has indeed been promoting greater fiscal co-ordination between the provinces and itself. But such a centralized policy approach does not come without costs. It has long been recognized that local stabilization policy is less effective than national policy because of the large leakages from any particular region. For example, if one province wants to stimulate local economic activity, much of the increased spending will go to goods and services imported from outside the region. But this is true whether or not the stabilization activity is undertaken by the provincial government or the federal government. The extent to which local stabilization policy results in leaks out of a region depends upon the size of the region, its economic makeup and the nature of the stabilization policy undertaken. While 75% of fiscal multiplier effects in the Atlantic provinces remain in that region, 92% of such effects remain in Ontario.(7) It also appears that leakages are greater when fiscal policy is dominated by tax changes than when such policy is undertaken on the spending side. While federal transfers into and out of a region do provide some degree of regionally sensitive stabilization, there may still be room for additional provincial initiative. Professor Edward Gramlich argues that the traditional lack of faith in sub-national fiscal policy is now misguided.(8) He believes that business cycles now seem to be originating from the real side of the economy and that regional economies differ sufficiently to make regionally differentiated stabilization policy a good idea. Moreover, leakages have diminished as a result of the growing importance of local, non-traded services. Consider the case of Ontario. The recent recession was largely an Ontario recession, in sharp contrast to the recession of the early 1980s. Moreover, the province had experienced a boom of unprecedented proportions in the late 1980s, causing the Bank of Canada to tighten its monetary policy in order to control the inflationary effects. That monetary policy, being national in scope, imposed costs on other sectors of the economy, even though they were not the source of the problem and even though parts of Canada outside Ontario were experiencing poor economic conditions. Federal fiscal instruments were also largely impotent: the tax and transfer system was channelling economic resources out of the province, but insufficiently to curb demand. Clearly, there was room here for tighter fiscal policy on the part of the Government of Ontario. The problem was not that the provincial government could not contribute to local stabilization, the problem was that it did not. In fact, the Ontario fiscal stance in 1988 and 1989 contributed to the boom rather than dampening it.(9) Had the government of Ontario conducted tighter fiscal policy in the late 1980s, its record of high deficits in the 1990s might not be so worrying, because its accumulated debt would be smaller. Just as important, had a countercyclical fiscal policy on the part of the province enabled the Bank of Canada to avoid its particularly tight stance in the late 1980s, the recessionary impact on the nation and on Ontario might have been reduced.(10) B. The Impact on Aggregate Deficits Any assumption of debt on an equal per capita basis would have a differential impact across the nation since the existing debt load varies enormously from province to province, whether measured on a per capita basis or as a percentage of provincial Gross Domestic Product. In addition, some provinces run operating surpluses while others run operating deficits. Whatever the amount chosen, some provinces would be pushed into a surplus position while others would still be in deficit. For example, even if the federal government assumed $200,000 million in provincial debt, Ontario and Nova Scotia would still have an annual deficit in excess of $200 per capita. The other provinces would be pushed to surplus, with the exception of Quebec, which would experience a small per capita deficit. The surplus could be substantial in some cases. According to Mendelson, it would amount to $200 per capita in Newfoundland, $300 per capita in Manitoba, $400 per capita in Saskatchewan, and about $650 per capita in Prince Edward Island. Even if the federal government assumed all provincial debt, some governments, Ontario and Nova Scotia for example, would continue to run deficits because their revenues today do not even cover the program costs of government. For a provincial agreement to balance future budgets, how much provincial debt would the federal government have to assume? For example, a total loan to the provinces amounting to $100,000 million would leave seven of ten provinces with deficits of $100 per capita or more. The Nova Scotia deficit would exceed $600 per capita while the Ontario deficit would exceed $500 per capita. Would these provinces agree to a constitutional requirement that they balance their budgets? If the required amount of a loan was $200,000 million or more, some provincial governments would find themselves in a substantial surplus position. If they were required to maintain the surplus over time, by establishing, for example, a sinking fund with the federal government with which to repay the loan ultimately, aggregate government deficits would be stable. If they lowered taxes by the appropriate amount or spent the windfall, aggregate government sector deficits would grow, even though the provincial government was in strict compliance with any balanced budget requirement. The Mendelson proposal could, then, be a recipe for growing government and growing deficits. Deficit reduction comes about because governments take appropriate action to control spending and raise revenues. Provincial governments have in the past run fiscal policies that are cyclically sensitive. Large provincial deficits have proved to be more temporary than their federal counterpart. The 1993 provincial budgets promise deficit cuts over one year which amount to 1% of GDP at the same time as the federal deficit is growing by about 0.4% of GDP (see Figure 1). Moreover, two provinces, Alberta and New Brunswick, have put in place legislation mandating balanced budgets, while three additional provinces are predicting budgetary balances over the next few years. All this is taking place without a bailout of their existing debt. The provinces are already putting in place the fiscal policies needed to reduce their deficits; if past performance is any indication, they will likely do a better job of it than the federal government. A bailout of the provinces' debt could lessen the need to take measures to balance their books. All governments are today facing a grave fiscal challenge – they are accumulating debt at rates that most Canadians consider unacceptable. In addition, however, there is clearly a mismatch between the tax-raising capacities of the provinces as a group and the expense of the programs for which they are responsible. Part of this gap is filled by transfers from the federal government. For several years, however, neither level of government has been completely satisfied with the structure of these transfers. In a nutshell – the provinces are responsible for programs with high growth rates yet the federal government dominates the personal income tax, the only tax with inherently high revenue growth.

It is likely that federal-provincial fiscal relations will change in response to economic pressures of the kind described above. The two proposals examined here are aimed at solving existing problems with respect to the misallocation of revenues between the two senior levels of government. One proposal is very centralizing; it relies on what amounts to a bailout of provincial debt and would grant virtually all stabilization powers to the federal government in exchange. The other proposal is at the opposite extreme; re-allocating taxes and eliminating the vertical fiscal gap would enable provincial governments to become much more independent in conducting their fiscal affairs. The federal government would lose much of its clout. What appear, on the surface at least, to be mundane and technical considerations about the allocation of tax room can thus have very profound effects on the governance of this country, and these profound effects could come about with little or no constitutional change. (1) G.C. Ruggeri, R. Howard, G.K. Robertson and D. Van Wart, "Rebalancing Canada's Fiscal Structure," Policy Options, December 1993, p. 27-30; and C.G. Ruggeri, R. Howard and D. Van Wart, "Structural Imbalances in the Canadian Fiscal System," Canadian Tax Journal/Revue Fiscale Canadienne, Vol. 41, No. 3, 1993, p. 454-472. (2) Michael Mendelson, Fundamental Reform of Fiscal Federalism, mimeo, 14 October 1993. (3) An expression of this conventional economic wisdom is found in: R.W. Boadway and P.A.R. Hobson, Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations in Canada, Canadian Tax Paper No. 96, Canadian Tax Foundation, Toronto, 1993. The discussion therein is broadly consistent with that found in I.K. Ip and J.M. Mintz, Dividing the Spoils: The Federal-Provincial Allocation of Taxing Powers, C.D. Howe Institute, Toronto, 1992. (4) Boadway and Hobson (1993) p. 150. (5) Mendelson (1993), p. 12. (6) Ibid. (7) Y. Rabeau, "Regional Stabilization in Canada," in J. Sargent, Research Coordinator, Fiscal and Monetary Policy, Vol. 21 in a series of studies commissioned for the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, Ottawa, 1986. (8) E.M. Gramlich, "A View from the Outside: The Relevance of Foreign Experience," paper presented to the Canadian Tax Foundation, Conference on Provincial Finances, Toronto, 30-31 May 1989. (9) T.J. Courchene, Rethinking the Macro Mix: The Case for Provincial Stabilization Policy, SPS Working Paper, No. 90-01, School of Policy Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, 13 February 1990. (10) Ibid., p. 36-37.

|