|

BP-389E

UNEMPLOYMENT

INSURANCE FINANCING:

Prepared by Kevin B. Kerr TABLE

OF CONTENTS B. The Impact of a Payroll Tax on Employment A. Experience-Rating in the United States B. Considerations for Implementing Experience-Rating in Canada

UNEMPLOYMENT

INSURANCE FINANCING:

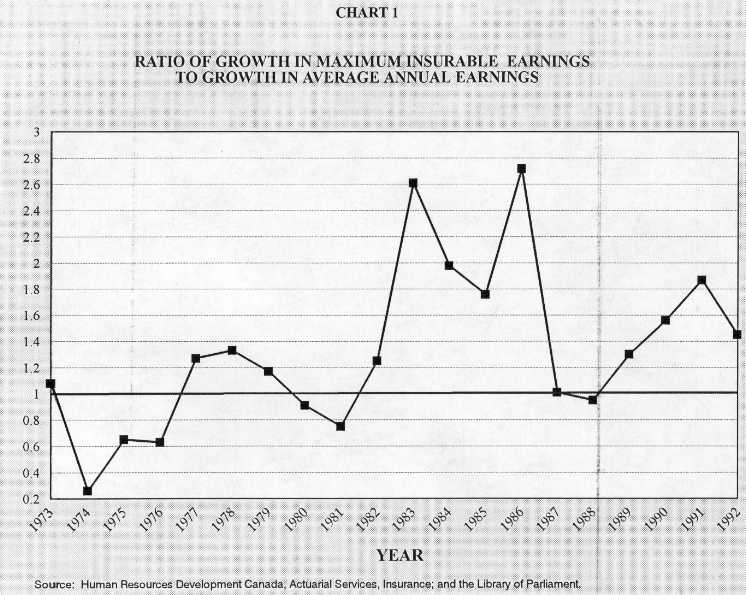

Since its inception in 1940, Canada's unemployment insurance (UI) system has undergone a number of significant changes. Initially, the function of unemployment insurance was to provide partial wage replacement to workers experiencing temporary periods of involuntary unemployment. Many workers were excluded from coverage, including those employed in work for which there was little risk of unemployment as well as those for which unemployment was almost a certainty (seasonal employment). Program financing was tripartite. Initial rates of contribution were based on eight earnings classes designed to ensure that employers and employees contributed equally (at least in terms of aggregate contributions). The federal government contributed 20% of the combined employer/employee contribution and covered the cost of program administration. Policy-makers expected the program to cost approximately $60 million annually, around 0.9% of GDP at the time. Today, UI is virtually universal in coverage (around 96% of the labour force). In addition to the regular benefits provided under the original system, the program now provides sickness, maternity and parental benefits; benefits to self-employed fishermen; benefits to eligible workers in approved work-sharing, job creation and training; and, more recently, funding for supplementary training allowances, starting a business, purchasing training courses, labour mobility and initiatives that encourage claimants to accept employment more quickly. Employers and employees are the sole contributors and employers pay 1.4 times the amount paid by employees. This year, estimated program expenditures and premium revenues are expected to total $20.3 billion (roughly 3.0% of GDP) and $20.1 billion respectively. Unemployment insurance has become the federal government's largest single program expenditure and second largest source of revenue. Today, UI exerts a major influence on the Canadian labour market. One aspect of this influence, and the subject of this paper, concerns the way in which unemployment insurance is financed. This paper focuses on three specific areas of financing: the tax base, premiums and the issue of experience rating. Two major features - the tax base and the tax rate (premiums) - determine a firm's (and worker's) tax liability under Canada's UI Program. The tax base ranges from 20% of maximum weekly insurable earnings to the weekly maximum.(1) The latter is determined by a statutory formula set out in section 47 of the Act.(2) Historical data on minimum and maximum weekly insurable earnings may be found in Table A of the Appendix. The purpose of indexing the tax base is to mirror growth in earnings and thereby maintain the real value of wage replacement. However, in view of the long lags inherent in the current formula, the rate of change in the tax base is necessarily sluggish in responding to current changes in average earnings. This failing becomes even more pronounced when the rate of change in nominal earnings is sustained. This is illustrated by the data presented in Chart 1 on the following page, which depict a persistent divergence between the rate of growth in maximum insurable earnings and growth in average annual earnings following the 1981-82 recession.

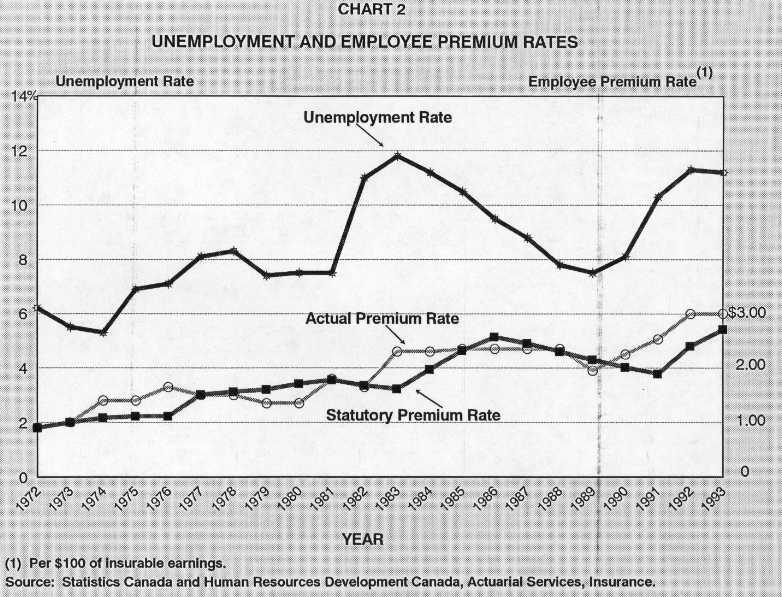

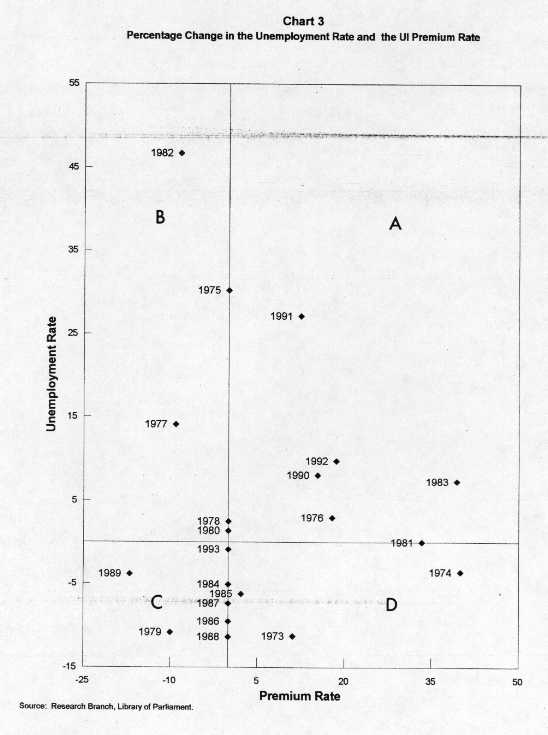

Throughout most of the 1980s, the current indexation formula continued to capture the wage inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s, despite the dramatic decline in the rate of inflation during this period. Between 1983 and 1993, average weekly earnings (industrial composite) increased by 45.6%. During the same period, maximum weekly insurable earnings increased by 93.5%, more than twice the increase in average weekly earnings. When the concept of maximum insurable earnings was introduced in 1972, the weekly maximum was roughly comparable to average weekly earnings. Today, it is approximately 1.4 times that amount, and this has undoubtedly contributed to higher program costs. If changes in the UI tax base are expected to be more responsive to changes in average earnings, modifications to the current indexation formula would appear to be in order. While several replacements exist, a simple and satisfactory one would be based on the product of maximum insurable earnings in 1975 (i.e. $185), as is now the case, and an index based on the ratio of average weekly earnings in the previous year divided by average weekly earnings in the reference year (1974) rounded to the nearest multiple of five. Using this formula, we find that, in 1994, maximum weekly insurable earnings would have been $630, almost one-fifth less than the current maximum. The proposed formula would yield a much closer relationship between annual changes in maximum insurable earnings and actual average earnings. One way of assessing the adequacy of the proposed formula is to measure the extent of the deviation between one and the ratio of the percentage change in maximum insurable earnings to the percentage change in average earnings. The smaller the deviation, the closer is the change in the maximum to the change in the average. Using this approach for the period 1975-93, we find that the current formula yields a mean absolute deviation of 0.52. The proposed formula, on the other hand, yields a mean absolute deviation of 0.32, almost one-half of that found for the current approach.(3) In the absence of a legislated premium rate, the Unemployment Insurance Act requires the Canada Employment and Immigration Commission to review the financial status of the Unemployment Insurance Account and establish each year a premium rate, subject to approval by the Minister of Finance and the Governor in Council. Specifically, sections 48 and 49 of the Act require the premium rate to be established so as to cover the adjusted basic cost of benefit. This is an amount equal to the average basic cost of benefit plus (minus) any amount necessary to remove or reduce a deficit (surplus) in the UI Account. The average basic cost of benefit refers to average total program costs, including the cost of administration, for the three-year period that ends concurrently with the second year preceding the year for which the average is computed. For example, the average basic cost of benefit for 1994 is equal to average total program costs for the years 1990, 1991 and 1992. Aggregate insurable earnings are averaged over the same period. The premium rate (normally expressed as some dollar amount per $100 of insurable earnings) necessary to cover the average basic cost of benefit is called the statutory rate; the rate for employees is roughly 41.6% of this, while the remainder is the rate for employers. In 1994, the statutory rate was calculated to be $7.37 per $100 of insurable earnings; the employee and employer rates were set respectively at $3.07 and $4.30 per $100 of insurable earnings. Although it was estimated that the statutory rate for 1994 would produce a small deficit in the UI Account by year's end, the government decided not to raise the premium rate above this level. Premiums have increased in both nominal and real (adjusted for inflation) terms since the introduction of the uniform premium rate structure. Between 1972-93, the nominal premium rate increased at an average annual rate of 6.9%, while the average annual rate of growth in real terms was 0.2%. Under the existing premium rate setting process, premium rates must necessarily rise to offset deficits in the UI Account. This is illustrated in Chart 2, which depicts a general upward trend in both the actual and statutory premium rates following an increase in the unemployment rate. The potentially destabilizing effects of this financing feature have long been recognized. Chart 3 presents a better graphic illustration of the relationship between movements in the unemployment rate and the actual premium rate during the period 1973-92. The coordinates located in quadrants A and C indicate that the unemployment rate and the premium rate moved in the same direction; in other words, premiums were set procyclically. Of particular interest are the years 1976, 1983, 1990, 1991 and 1992, in each of which the premium rate increased while the unemployment rate was rising. Premium rate movements during these years were somewhat perverse in that they added to the cost of labour and thereby dampened the creation of employment during a period when jobs were needed most.(4)

In view of the fact that the private sector is now fully exposed to cyclical variations in premium rates (i.e. the government no longer contributes to the UI Account), closer attention might be paid to providing greater stability in premium rates. Ideally, the financing of UI would better serve a recovery if premiums increased during periods of economic growth and not during a recession. In addition, steps could be taken to minimize year-over-year changes in premium rates (annual increases under the current process have been as large as 40%). In this context, consideration might be given to allowing the UI Account to maintain a long-term surplus to help reduce the size of year-over-year changes in premium rates. It is estimated that the financial status of the UI Account would have been in a breakeven situation (i.e. a small surplus of $292 million) today had employee premiums been held at $2.57 per $100 of insurable earnings since 1972.(5) B. The Impact of a Payroll Tax on Employment As noted above, firms must pay a UI premium rate equal to 1.4 times that paid by employees. These premiums represent a tax on labour and, as such, have an impact on the firms' hiring decisions. Since the inception of the current Unemployment Insurance Act, the burden of this tax has grown. In 1973, net employer contributions to the UI Account totalled $541.3 million, or approximately 1% of total salaries and wages (see Table B in the Appendix). In 1993, net employer contributions amounted to roughly $10.8 billion, or 3% of total wages and salaries. In other words, the relative size of this tax has tripled over the past 20 years. As higher UI payroll taxes (and other payroll taxes) increase the cost of production, policy-makers are now beginning to pay greater attention to the potential adverse impact of this tax on employment. The recent concern expressed by the federal government (and the private sector) over the level of UI premiums stems from the view that this tax, like any other payroll levy, is a tax on employment. As such, the demand for labour may decline in response to the UI premium's impact on profitability and/or the relative price of labour.(6) The effects of switching an existing payroll tax may also exert an impact on employment even though the incidence of the tax remains the same over the long-term. For example, switching from employee to employer taxation can reduce employment in the short-term if real wages rise due to lags in the adjustment of prices and nominal wages.(7) In recognition of the potential adverse impact of UI premiums on employment, a premium rebate (up to $30,000) was offered to small businesses in 1993 to encourage the hiring of additional workers. More recently, The Minister of Finance announced that UI premiums would be frozen at $3.00 per $100 of insurable earnings for the years 1995 and 1996. In the absence of this measure, it is estimated that the statutory premium rates for 1995 and 1996 would have been $3.30 and $3.25 in 1995 and 1996 respectively. Although the impact of the premium reduction is expected to generate 58,000 jobs by the end of 1996, not all of this is attributed to a decline in labour costs due to lower UI premiums. It must be remembered that employees will also benefit from this measure through an increase in disposable income and this is expected to increase both output and employment.(8) The options for minimizing the adverse employment effects of the UI payroll tax are limited at best. The most obvious one, critical in terms of lower UI premiums, is to reduce program costs. Aside from lower unemployment, downward pressure on the need to generate revenues can be achieved only by reducing UI expenditures (e.g. lower benefit entitlement) and/or by shifting the financial liability of certain program features (e.g. UI developmental uses) away from premiums to general revenues. Another option would be to lower employers' share of program costs. As previously noted, employer and employee contributions are not equal (employers pay 1.4 times the amount contributed by employees). As employees are the main recipients of support under the program, there does not appear to be any strong rationale for making employers pay for 58% of the costs. The higher employer contribution is supposed to reflect the fact that employers have more control over program costs (e.g. layoff decisions) than employees, but a far more effective mechanism would be to rate premiums according to a firm's layoff experience. The structure of unemployment insurance premiums has long been considered a distortionary feature of Canada's unemployment insurance system. As all firms pay a uniform premium, this financing structure amounts to a cross subsidy between firms with stable employment and firms with unstable employment. It is surmised that the latter group of firms relies on unemployment insurance as part of the remuneration package offered to workers. In Canada, quantity adjustments in the form of temporary layoffs are commonplace among firms, particularly seasonal ones, responding to a downturn in the demand for output. Recent data suggest that 80% of those laid off with a recall date are in fact recalled; 58% of those laid off without a recall date are recalled; and 26% of those laid off with no expectation of being recalled at the time of the layoff are recalled. Overall, approximately 56% of all layoffs end with recall.(9) Evidence also suggests that these temporary layoffs generate a considerable amount of repeat use of the unemployment insurance system. Over 40% of chronic repeaters (i.e., those with five or more benefit claims between 1978 and 1989) supported their claims with insurable employment from three or fewer firms.(10) Table 1 presents a sectoral breakdown of benefit/cost ratios for the period 1990-92. One way to eliminate the cross subsidies inherent in these data is to "experience-rate" premiums. That is, introduce a financing structure that charges firms premiums based on their benefit claims; firms whose layoff behaviour generates higher benefit payments pay higher premiums than firms associated with more stable employment patterns and lower benefit payments. The price of output in the former group of firms would rise and thereby lower the demand for output and, consequently, the demand for labour.(11) Over time, the relative size of employment in the layoff-prone sector would decline and increase in sectors associated with stable employment. Moreover, it is expected that the overall level of unemployment would decline. This approach is more efficient and equitable than the current practice. If employers' UI costs reflect their labour allocation decisions, the demand for their output will be sensitive to these decisions. Firms would no longer produce excessive levels of output and insurance costs would be borne by those firms that generate claims for benefits. Furthermore, firms would be more likely to record information on separations more quickly and diligently, which, some suggest, could lead to lower overall administration costs. TABLE 1

Source: Human Resources Development Canada, UI Analysis Directorate, August 1994, unpublished. The misallocation effects associated with uniform unemployment insurance premiums have been discussed for a long time as has the notion of charging risk-related premiums. Probably the most comprehensive treatment afforded the issue of risk-related premiums was provided by a study group (formed by the Unemployment Insurance Commission in 1967 following the Gill Commission) to examine all aspects of restructuring Canada's unemployment insurance system. The study group's report strongly recommended incorporating risk-related premiums into the program's financing structure. It proposed a fairly complex premium allocation formula where employer premiums varied across firms and industries, and employee premiums varied across industries (the government continued to be responsible for certain program costs). In reality, the concept of experience rating has never found favour among policy-makers in this country. Although the current Unemployment Insurance Act provided for regulatory making authority to experience-rate premiums it was never used; this provision was repealed in 1977. Even though the demand-side of the labour market is known to have an influence on repeat UI use, recent major reviews of UI decided against recommending an experience-rated UI Program.(12) Opposition to experience-rating is based on several arguments. It is argued that this type of financing structure would undermine UI's ability to transfer income from low to high unemployment regions of the country. This is undoubtedly correct, although it must be remembered that the cross subsidy inherent in a uniform premium structure creates a greater need for interregional transfers. Critics maintain that there is no point in experience-rating premiums if the cost of benefits subjected to this type of financing is only a small proportion of overall costs. This argument has been raised in the context of a tripartite financing structure and also in the context of specific proposals that would constrain the risk-related premiums of certain firms, especially small employers and highly seasonal firms. As noted above, the government no longer contributes general revenues to the program and there is no strong rationale for minimizing the impact of a risk-related financing structure on certain firms. Given our reliance on external trade and the seasonal influences experienced in some parts of the country, critics maintain that many firms will not be able to stabilize their workforces, even if their unemployment insurance premiums are rated. Nevertheless, there is some scope for these firms to enhance work force stability and also contribute to the goal of economic efficiency, the primary objective of experience-rating premiums. A. Experience-Rating in the United States The method of financing unemployment insurance in the United Sates differs from that in Canada in several respects. While both countries have bi-partite financing structures, employees in the United States, save those in Alaska, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, do not contribute to the system. In other words, employers in the United States are essentially the sole private sector contributors to regular unemployment insurance. Unlike the case in Canada, the federal government in the United States pays for extended benefits (i.e. additional benefits paid during periods of high unemployment). This feature was dropped from Canada's program at the beginning of this decade. The tax base in both countries also differs in a number of ways. As noted above, employers in Canada pay the same tax rate (premium) irrespective of the number of unemployment insurance claims they generate. The United States, on the other hand, is unique in that it is the only country in the world that attempts to experience-rate unemployment insurance premiums.(13) The actual tax rate is a combination of federal and state levies. The federal unemployment insurance tax rate has been 6.2% of taxable payroll (i.e. the first $7,000 earned in a calendar year) since January 1985. The standard rate in most states is 5.4%, the maximum allowable credit that can be applied against the federal levy.(14) It is the state tax that is subjected to experience rating, although, as noted below, experience-rating is incomplete. One of four methods is used by the states to calculate experience-rated tax rates. These include the reserve-ratio formula, the benefit-ratio formula, the benefit-wage-ratio formula and the payroll variation plan. Employed by 30 states, the most popular method of relating unemployment insurance taxes and unemployment (layoff) experience is the reserve-ratio formula. Under this approach, each firm has a separate account which records its reserves (i.e. the difference between contributions made and benefits paid). Employers are required to accumulate and maintain a specified reserve before rates can be lowered. The tax rate is based on some measure of reserve "adequacy," typically, the ratio of total accumulated reserves to the firm's taxable payroll. Rates are assigned according to a schedule based on specified ranges of reserve ratios - the higher the ratio the lower the rate. Schedules change according to total reserve levels in a given state fund. Hence, although a lower or higher rate may be assigned to a firm in the absence of a change in experience, the firm's relative state-specific tax rate would presumably remain unchanged. Currently, 17 states use a benefit-ratio formula to experience-rate unemployment insurance taxes. Under this approach, contributions are disregarded and the ratio of benefits paid to payroll is used to determine the tax. The basis for this approach is the belief that a tax rate approximating this ratio will cover the firm's liabilities. However, in practice, states employing this method have found the need to use additional tax rate schedules to ensure adequate reserves in their funds. Under the benefit-wage-ratio formula, employed in only two states, a firm's experience is determined by the proportion of the firm's payroll paid to workers who separate during some base period. The higher the ratio, the higher the rate. Only one separation per worker per benefit year is recorded. This approach implicitly assumes that separations, and not the duration of benefits, should be considered in determining each firm's experience. The payroll variation formula, used only in Alaska, bases experience on changes in a firm's payroll and ignores benefits paid to laid off workers. A firm's layoff (unemployment) experience is measured by negative changes in payroll on a quarterly basis. Alaska has 10 classes of negative payroll changes for which separate tax rates are applied. If there are no downward changes in payroll over a three-year period, the firm is assessed the lowest unemployment insurance tax rate. Irrespective of the formula used, experience-rated tax rates are typically constrained. At the low end, few states permit a zero tax rate and the average minimum is around 0.5% (when state fund balances are less than a specified amount, minimum rates are generally in excess of 1.0%). Although the highest maximum tax rate is 10% (found in Arizona and Tennessee), 19 states impose a maximum rate of 6.0% or less.(15)(16) In states that use benefit-related formulas, not all benefits are included in determining a firm's experience. One of the most important exclusions in this regard is for workers employed for a short period of time; presumably, this is so that firms will not be discouraged from hiring.(17) Benefits paid to workers who experience short periods of unemployment are often omitted, as are benefits paid to workers who voluntarily leave employment. It is interesting to note that five states (Arkansas, Colorado, Maine, North Carolina and Ohio) exclude from a firm's unemployment experience those benefits paid to seasonal workers who experience unemployment during the off-season (i.e., only benefits paid to seasonal workers who experience unemployment during the season are considered).(18) From a Canadian perspective this exclusion seems perverse, since most proponents of experience-rating seek to eliminate seasonal workers' claims for benefits during the off-season. These and other program features suggest strongly that experience rating in the United States is incomplete; studies suggest that the degree of experience rating in the United States varies both among and within industrial sectors in a given state, varies from state to state, and has declined over time (primarily because increases in the taxable wage base have not kept up with those of benefits or total wages).(19) While there is evidence that high unemployment industries in the United States have a larger share of employment than would be the case under complete experience-rating, the magnitude of the misallocative effects of incomplete rating is not known. In terms of employment stability, estimates suggest that incomplete experience-rating lowers retention rates and raises the unemployment rate. One study, for example, estimated that, in a typical year, up to one-fifth of all layoffs could be attributed to the subsidy inherent in incomplete experience-rating.(20) B. Considerations for Implementing Experience-Rating in Canada Although the benefits of incorporating a user pay-like financing structure into our unemployment insurance system seem obvious, governments in Canada have consistently eschewed this approach. Nevertheless, if Canada were to adopt experience-rating there are several areas, as noted above, where improvements could be made vis-à-vis the United States model in determining unemployment insurance tax liabilities. For instance, a more effective system of rating would result if ceilings on tax rates were avoided and all costs generated by individual firms were recorded (including temporary employment resulting in short benefit periods as well as frivolous administrative costs such as unwarranted appeals). In reality, however, significant pressure could be expected from individuals and regions dependent on unstable sectors to cap experience-rated premiums. If a ceiling is imposed, the gap between minimum and maximum rates must be large enough to ensure that sufficient incentives exist for firms to stabilize employment (experience-rated premiums for governments and large firms could be unconstrained). Although absent from the discussion above, firms with deficits in their individual accounts should be required to pay interest, while those with surpluses should receive interest (this is not done in the United States). Firms should be encouraged to build up reserves so as to minimize the adverse effects of structural and cyclical influences on the overall fund. It would not be necessary, and would probably be administratively too costly, to rate employee premiums. Presumably employees have little control over involuntary separations from employment and a total disqualification for voluntary separations (including workers released because of misconduct) is now a feature of our program. It is clear that Canada's unemployment insurance system is structured, in part, to redistribute income from low unemployment areas of the country to regions experiencing high unemployment. Under experience-rating, firms should not be assessed higher tax liabilities simply because the federal government wants to achieve some income redistribution objective via a benefit structure that delivers a significant dollar value of benefits on the basis of regional unemployment. Hence, all claimants should be subject to the same benefit entitlement provisions, irrespective of geography, and the government's income redistribution goals could be met via another transfer mechanism. In addition, firms' assessed tax liabilities should not include special benefits or additional benefits paid under the guise of developmental uses; these benefit expenditures rest largely outside the decision-making scope of firms. Over the years, Canada's unemployment insurance system has grown significantly and today it is thought to exert a major influence on the labour market. One source of this influence stems from the way UI is financed. Today, UI premiums levied on payroll constitute the sole source of program revenue. Employers contribute 1.4 times the contribution of workers. As a tax on labour, UI premiums are thought to have an adverse effect on the demand for labour. The current uniform premium rate structure is also thought to contribute to inefficient resource allocation and higher unemployment. In recent years, UI-related labour costs have escalated, in part, because of the way in which the tax base is indexed. The long lag inherent in the indexation formula has contributed to wide differences between annual growth in maximum insurable earnings (and benefits) and actual earnings. Premium rates have also exhibited a great deal of volatility, sometimes rising while the economy is still at the bottom of the business cycle. In view of the shortcomings noted above, consideration might be given to ensuring that changes in maximum insurable earnings more closely reflect the trend in actual earnings. In addition to lower premiums, the premium rate setting process could be redesigned so as to stabilize premium rates and to minimize the potential destabilizing effect of procyclical movements in premiums. A final proposal, undoubtedly the most contentious raised here, is that serious thought should be given to basing premium rates on firms' layoff experiences. Recent evidence strongly suggests that the current flat-rate premium structure induces some firms to use the UI Program as part of the remuneration package they offer to their workers. This practice has contributed to growth in unstable employment and higher levels of unemployment. Anderson, Patricia M. and Bruce D. Meyer. "Unemployment Insurance in the United States: Layoff Incentives and Cross Subsidies." Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 11, No.1, 1993, p. S70-S94. Brown, Eleanor P. "Unemployment Insurance Taxes and Cyclical Layoff Incentives." Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1986, 50-65. Corak, Miles. "Unemployment Insurance, Temporary Layoffs and Recall Expectations." Canadian Economic Observer, Statistics Canada, May 1994, p. 3.1-3.15. Dahlby, Bev. "Taxation and Social Insurance." Chapter 4, in Taxation to 2000 and Beyond. Eds. Richard M. Bird and Jack M. Mintz. Canadian Tax Foundation, Canadian Tax Paper No. 93. 1992. Employment and Immigration Canada. Unemployment Insurance in the 1980s. Task Force Report. Ottawa, July 1981. Human Resources Development Canada. "Policy Considerations With Respect to the Unemployment Insurance Program." Presented to the Standing Committee on Human Resources Development, 21 February 1994. Kesselman, Jonathan R. Financing Canadian Unemployment Insurance. Canadian Tax Paper No. 73. Canadian Tax Foundation, April 1983. Neisner, Jennifer and James R. Storey. "Unemployment Compensation in the Group of Seven Nations: An International Comparison." Prepared by the Congressional Research Service for the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance and the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means. April 1992. Nicholson, Walter. "Unemployment Insurance Financing: Lessons from the United States." Prepared for the Commission of Inquiry on Unemployment Insurance." March 1986. OECD. Employment Outlook. Paris, July 1990, p. 153-77. Topel, Robert H. "Experience-Rating of Unemployment Insurance and the Incidence of Unemployment." Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. XXVII, April 1984, p. 61-90. United States, Department of Labor. Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws. Washington, 2 January 1994.

TABLE A

(1) Between 1972 and 1978 minimum weekly insurable earnings for any province was the lesser of one-fifth of maximum weekly insurable earnings and 20 times the minimum hourly wage rate. The minimum reported in the table is the one applicable to the greatest number of provinces. For the years 1979 and 1980, minimum insurable earnings were 30% of the maximum. Thereafter, minimum insurable earnings were equal to 20% of maximum weekly insurable earnings. Source: Human Resources Development Canada, Actuarial Services, Insurance, August 1994.

TABLE B

(1) Per $100 of

insurable earnings. Source: Statistics Canada, Unemployment Insurance Statistics, 1994; and Human Resources Development Canada, 1994-95 Main Estimates, Part III.

(1) It should be noted that workers can also satisfy minimum insurability by working at least 15 hours per week. Consequently, the minimum tax base on which premiums can be levied is theoretically less than 20% of maximum weekly insurable earnings. It should also be noted that insurability is determined on the basis of minimum weekly earnings (or hours) in relation to individual jobs. Hence, a worker's earnings (or hours) associated with multiple part-time jobs are not aggregated for the purposes of determining insurability. In other words, a worker's total weekly work-time may well exceed the minimum insurability rules, but not be insurable. This feature of the program likely warrants closer examination, given the growing trend in part-time work. (2) This formula is equal to the product of $185 and the earnings index rounded to the nearest multiple of five dollars. The earnings index is calculated as the ratio of average annual earnings for an eight-year period ending concurrently with the second year preceding the year for which the calculation applies, divided by the base year (i.e. average annual earnings for the period 1966-77). (3) This technique was used by Kesselman (1983) in ranking three possible indexing methods, one of which was proposed by the Task Force on Unemployment Insurance (1981). Kesselman's best performing formula was the ratio of average weekly earnings for the previous year divided by average weekly earnings in 1970 multiplied by $150 (maximum insurable earnings in 1972). (4) Though not a rigorous statistic, a correlation coefficient was computed for these variables using annual data for the period 1972-93. The value of the correlation coefficient was found to be 0.78 when the premium rate was expressed in nominal terms and -0.41 when it was expressed in real terms. Estimates based on quarterly data (i.e. the difference between xt and xt-4) for the same variables suggest that there is virtually no relationship between the two. (5) This assumes full premium financing (i.e. no government contributions) over the entire period, 1972-93 (Human Resources Development Canada, Actuarial Services, Insurance). (6) It is difficult to establish who ultimately bears the cost of employer UI premiums: employers may bear this cost in the form of reduced profits, consumers may bear this cost in the form of higher prices and/or employees may bear this cost in the form of lower wages. Empirical estimates of tax shifting appear to suggest the existence of backward shifting, although it is unlikely that payroll taxes are shifted fully to employees, even in the long run. (Kesselman (1983), p. 21; and Bev Dahlby (1992) p. 113. (7) OECD, Employment Outlook, Paris, 1990, p. 169. (8) A quarterly macroeconomic model called FOCUS (Institute for Policy Analysis, University of Toronto) was used to generate this estimate. Although government documents suggest that the reduction in premiums will generate 40,000 jobs by the end of 1996, this estimate in fact measures the net effect of the interim UI reform announced in the February budget (i.e. the higher entrance requirement and reduced benefit entitlement provisions are expected to reduce employment by 19,000 jobs). It should be noted that the net employment effect of these measures is based on a macroeconomic policy response which pursues exchange rate stability. (9) Miles Corak, "Unemployment Insurance, Temporary Layoffs and Recall Expectations," Canadian Economic Observer, Statistics Canada, May 1994, Table 2, p. 3.6. (10) Ibid., p. 3.7. (11) The extent to which prices rise over the long-term depends on how much employers are able to pass on higher unemployment insurance payroll taxes to employees and/or realize lower profits. Although some argue that firms have no incentive to stabilize employment if the tax is shifted to consumers, it should be noted that employment stability would lower costs and thereby raise profits. (12) In 1981, the Task Force on Unemployment Insurance in the 1980s rejected experience-rating because it questioned the ability of this type of financing arrangement to provide a big enough incentive to employers to stabilize employment; moreover, it would make the program more complex and less equitable. Although the Macdonald report was generally receptive to the concept, it concluded that experience-rating was a matter requiring more detailed study and discussion. The Forget report was less receptive; it opposed experience-rating on the grounds that it was over rated in terms of modifying firms' and workers' behaviour and was too costly to administer. (13) It should be noted that, although Italy does not vary premium rates according to experience, it does impose higher premiums on industrial and construction firms (see Jennifer Neisner and James R. Storey, "Unemployment Compensation in the Group of Seven Nations: An International Comparison," prepared by the Congressional Research Service for the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance and the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, April 1992, p. 8.) (14) United States Department of Labor, Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws, January 1994, p. 2-1. (15) Ibid., Table 206, p. 2-35. (16) The rationale for a non-zero minimum rate is that all firms should contribute something to an insurance program which pools the risks of unemployment. A cap at the high end is intended to reduce the tax burden of cyclically sensitive firms. (17) One study estimated that, in the six states examined, these so called "free layoffs" accounted for between 16.3% and 37.2% of all 1981 separations that resulted in an unemployment insurance claim (Patricia M. Anderson and Bruce D. Meyer, "Unemployment Insurance in the United States: Layoff Incentives and Cross Subsidies," Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1993, Table 4, p. S84). (18) Ibid., p. 2-9. (19) Walter Nicholson, "Unemployment Insurance Financing: Lessons from the United States," prepared for the Commission of Inquiry on Unemployment Insurance, March 1986, p. 31-2. (20) Robert H. Topel, "Experience Rating of Unemployment Insurance and the Incidence of Unemployment," Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. XXVII, April 1984, p. 62. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||