|

BP-434E

WORLD FISHERIES:

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S FISHERIES A. Industrialization and Overcapacity B. The Expansion of World Fishing Fleets UNDERLYING CAUSES OF OVERFISHING B. Social and Political Factors A. UN Agreement on Straddling Stocks and Highly Migratory Species B. FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

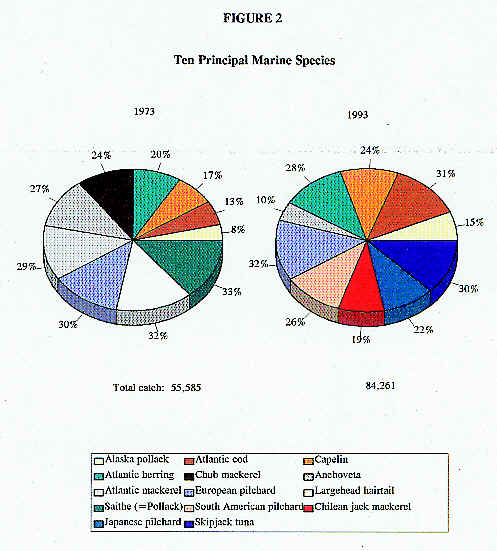

WORLD FISHERIES: Most Canadians are aware of the collapse of Atlantic groundfish stocks like the northern cod and of the problems that beset British Columbia’s salmon fisheries. Canada’s experience with its fisheries is not unique but is rather part of a global phenomenon in which relentless fishing pressure and environmental degradation are pushing fish stocks to the brink of destruction. At one time, the oceans and the shoals of fish that swam in them seemed so vast that they could hardly be affected, far less harmed, by human activities. The nineteenth-century biologist Thomas Huxley wrote "I believe that the cod fishery...and probably all the great sea fisheries are inexhaustible."(1) Huxley, like many others, was wrong. Most of the world’s most important fish stocks have now been fished to the limit of sustainability and beyond into decline. A number have collapsed altogether. Overfishing has altered the ecological balance in some areas; as commercially valuable species have been exhausted they have been replaced by other, less commercially desirable, species. Deforestation, industrial pollution, agricultural runoff, domestic sewage, and urban development have degraded fish habitat and reduced productivity. Much of the most important and productive coastal habitat, consisting of estuaries, mangrove, wetlands, and coral reefs, has already been damaged or destroyed by development. Excess capacity and overcapitalization of many of the world’s fishing fleets have resulted in overfishing. In part this is because many countries, for social and political reasons, have subsidized their fishing industries. As a result, fishing fleets have grown too large to be supported by the resource and are neither ecologically sustainable nor economically viable in the long run. The consequences are the depletion of stocks and financial losses to both private and public sectors. The combined assault of overfishing and degradation of the marine habitat threatens the viability of marine ecosystems and undermines the stability of a vital economic resource. The security of one of the most important sources of food for much of the world’s population, especially in developing nations and coastal communities, is at risk. Traditional patterns of use have already changed as small-scale, artisanal fishing has been displaced by industrial fishing, often with the result that local communities are denied their traditional source of protein. The fundamental causes of the crisis are well understood and without significant change the final outcome may be all too predictable. Yet, international and national action to curb overfishing and protect fish habitat has been slow. Frequently, instead of scaling back fishing effort as stocks become depleted in one area, fleets have simply moved to new fishing grounds, often off the coasts of developing nations, and have turned to new "underexploited" stocks. Competition for dwindling fish stocks has resulted in international hostility (for example between Canada and Spain on the Grand Banks; between France and Spain in the Bay of Biscay; between Norway and Iceland in the Barents Sea). This paper outlines the state of the world fisheries, examines the underlying causes and solutions, and summarizes the principal remedial actions that have been taken at the international level. THE STATE OF THE WORLD'S FISHERIES In its 1995 report on the state of the world’s fisheries, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) stated that, at the beginning of the 1990s, 69% of the world’s conventional species were either fully exploited, overexploited, depleted, or rebuilding from a depleted state. The FAO concluded that the operation of the world’s fisheries as they existed could not be sustained and that significant ecological and economic damage had already occurred.(2) The dramatic increase in world fisheries production is illustrated in Figure 1. In just four decades, between 1950 and 1989, total world fisheries production (including fresh water and aquaculture) increased by 500%, from 20 million tonnes to just over 100 million tonnes. By comparison, the total world marine catch at the beginning of the century was only 3 million tonnes. Global capture fisheries peaked in 1989 but the decline since then has been offset by increased aquaculture production. Virtually all major areas of the world’s oceans have been affected but some of the hardest hit regions have been in the Atlantic Ocean, particularly the northwest and southeast, where catches have fallen, by over 40 and 50% respectively, from their peak in 1973.(3) The only major ocean area in which catches are still increasing is the Indian Ocean, where mechanized fishing is just beginning to take hold. Using a different measure of stress, in the East Central Atlantic the FAO classifies 95% of demersal stocks,(4) 97% of pelagic, 94% of crustacean and 93% of molluscan as being fully fished, overfished, depleted or recovering.(5) The aggregate figures do not convey the full nature of the crisis as they do not reflect the decline of some of the most important species. In 1973, for example, the catch of Atlantic cod, one of the world’s most sought-after species, was second in tonnage only to that of Alaskan pollock but by 1983 Atlantic cod had already fallen to fifth place and by 1993 it had fallen to ninth place (Figure 2).

Source: FAO. Stocks of demersal fish of of the northwest Atlantic have been particularly hard hit. Some of the world’s once most productive fisheries, on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland and the Georges Bank off the New England states of the U.S., are essentially closed following the depletion of many of the most important groundfish stocks. One of the most dramatic collapses was that of the northern cod, historically the most important stock of the northwest Atlantic, which, in only four years, between 1990 and 1994, was reduced in numbers by a factor of a hundred.(6) The northern cod is not an isolated case. In the 1970s, the stock of north sea herring, an important staple for northern European countries, collapsed. The catch fell from several million tonnes to a mere 52,000 tonnes in 1977.(7) Although a temporary ban on fishing allowed the stock to recover, it is nowhere near the levels of last century.(8) Stocks of other species, including capelin, anchovy, pilchard, abalone, and sardines, have also suffered collapses.(9) The western Atlantic breeding population of the northern bluefin tuna, probably the world’s most valuable fish on an individual basis,(10) is reported to have fallen by 90% since 1975, from an estimated 250,000 individual fish to just over 20,000.(11) Global stocks of southern bluefin are at an all-time low. Other species of tuna are under considerable pressure as world catches of tuna have doubled over the last 11 years to a catch that was 3.2 million tonnes in 1993 and is expected to exceed 4 million tonnes by the year 2000.(12) Lower catches of more desirable species have been offset by switches to less valuable species, often those situated lower on the food chain, capelin for example. This action can be self-defeating, for not only is it less profitable(13) but the switch can impair the recovery of more valuable stocks by depleting their food supply. It is said that there are now virtually no species of marine fish left that can be economically exploited.(14) A. Industrialization and Overcapacity Although overfishing is often characterized as "too many fishermen chasing too few fish," the real problem is not so much the number of fishermen as the enormous harvesting capacity made possible by an industrial approach to fishing. The industrial assault on fish stocks is characterized by an expansion in gross tonnage of fishing fleets, augmented by new technology, much of which has been developed since the Second World War.(15) B. The Expansion of World Fishing Fleets Between 1970 and 1992, the size of the world’s industrial fishing fleet doubled in both total tonnage and number of vessels (Figure 3). By 1992, there were 3.5 million fishing vessels representing 26 million gross register tons (GRT). Growing at twice the rate of the global catch, world fishing fleets now have twice the capacity needed to harvest the maximum sustainable yield of the oceans.(16)

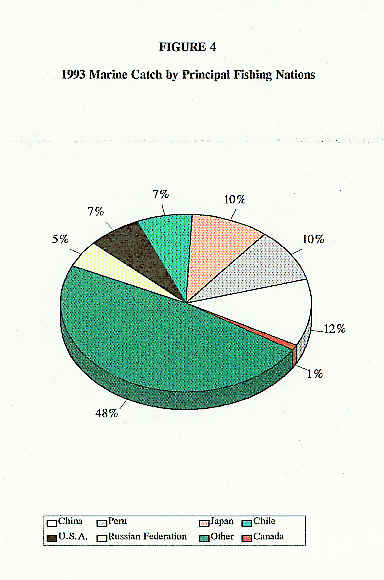

Asia accounts for the greatest share of the world’s fishing fleet with 42%, followed by the former Soviet Union (30%), Europe (12%), North America (10%), Africa (3%), South America (3%), and Oceania just 0.5%.(17) Six states alone (China, Peru, Japan, Chile, the U.S., and the Russian Federation) harvest fully half of the world’s saltwater catch(18) (Figure 4). Canada, although one of the world’s major seafood exporters, accounts only for a little over 1.3% of the world’s marine catch. Mechanical power has replaced human effort and sail. Modern fishing vessels, many much larger than their older counterparts, can cross the world to distant fishing grounds, fish in deep and dangerous waters, stay at sea for months at a time, and process their catch on board. The harvesting capacity of fishing gear has also been vastly amplified by mechanical power. A trawl net hauled by a hydraulic winch can scoop up many tonnes of fish in a single set. The capacity of more traditional gear like longlines can be greatly increased by hydraulic winches and automatic hook baiters. The scale of some modern fishing gear is hard to comprehend; for example, 80-mile long lines with thousands of hooks,(19) the "Gloria" supertrawl net (whose maw of 110 by 170 metres is large enough to engulf 12 Boeing 747s),(20) and 40-mile drift nets.

Source: FAO. New electronic technology also plays an important role. Sonar allows the skippers of fishing boats to locate schools of fish and track them down more efficiently. Satellite and aerial surveillance also help fishing boats to locate their prey. Navigational aids such as Global Positioning System (GPS) and radar allow fishing vessels not only to reposition themselves on prime fishing grounds (such as spawning grounds) with great accuracy but to go to sea in relative safety in conditions that would have kept traditional fishing boats in port. Technology has also played a major role in expanding the market base for fish. As fresh fish is a highly perishable commodity, its traditional markets were usually limited to coastal regions and their hinterlands, while fish from distant fishing grounds was traditionally dried or salted; however, the combination of modern transportation and cold storage technology means that "fresh" fish can be available across the world in virtually any season. The industrial/market approach also tends to encourage considerable wastage. In order to satisfy market demands and maximize profits, commercial fishing fleets target the most highly valued species and sizes of fish. The "bycatch" of lower-valued species, consisting of species for which the vessel does not have a licence or quota but that are caught along with the target species, is simply dumped. Quota systems intended to limit catches to sustainable levels encourage the practice of "high-grading," that is the dumping of the smaller or otherwise less marketable portion of the catch in order to maximize profits. The FAO estimates recent levels of bycatch and discards at 27 million tonnes a year but the figure could run as high as 39.5 million tonnes.(21) These remarkable figures do not represent the total (and unknown) mortality level, which includes the so-called "escapees." Some fisheries are notorious for their high bycatch. The southern U.S. shrimp fishery reportedly has a bycatch ratio of ten to one; that is, for every pound of shrimp, ten pounds of unwanted fish are killed. The problem is made even worse by the fact that the bycatch includes not only low-valued species but the juveniles of other commercially valuable species. Total discards in the U.S. shrimp fishery are estimated at 175,000 tons (=160,000 tonnes) of juvenile fish; this fact has contributed to an 85% decline in the population of commercially important bottom fish such as groupers and snappers during the past 20 years.(22) The discards can also include commercially valuable fish. A study commissioned by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game estimated that in 1994 factory trawlers in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska discarded a record 341 million kilograms of edible fish.(23) Other incidental victims of large-scale fishing include marine mammals, seabirds and turtles. In 1990, 42 million animals were ensnared in highseas drift nets(24) and the survival of several species of marine mammals and six of the 14 species of albatross is threatened by fishing methods.(25) A World Wildlife Fund study in the Southern Ocean found that more than 44,000 albatrosses were being killed annually by Japanese longliners fishing for southern bluefin tuna.(26) The incidental loss of marine wildlife caused by large-scale drift nets prompted the United Nations in 1992 to enact a ban on nets longer than 2.5 kilometres; nevertheless, a number of countries, including Italy, France and Ireland, continue to use them.(27) Environmental degradation has a major impact on fisheries resources. Industrial and agricultural effluents and municipal sewage may pollute waters to the point where they cannot support fish populations or they may simply contaminate the fish so that these are not suitable for consumption. Major rivers, which have historically served as transportation routes and therefore the focus of human settlement and industrial development, have been especially vulnerable to this kind of damage. Land use also has an effect on fish habitat; for example, habitat may be lost to urban development. Deforestation causes increased run-off and loss of water quality because of siltation and alteration of water temperature. Anadromous fish such as salmon are particularly sensitive to these effects since damming rivers for hydro-electric power, irrigation or flood control impedes the movement of species that return to fresh water to spawn, effectively causing a loss of habitat. Wetlands, which often provide important spawning grounds or nursery areas for juvenile fish, may be taken out of production by being drained to provide land for agricultural use or urban development. Fishing methods too are responsible for environmental damage. Heavy trawl nets have caused significant alteration to the sea bed by levelling out the bottom, cutting off coral heads in some areas, and turning over sediments, thereby disturbing and often killing the bottom-living fauna. The vast majority of shallow continental shelves have already been scarred by fishing;(28) in the North Sea, most of the seabed is dragged by bottom trawlers at least once each year.(29) The detrimental impact of other fishing methods practised in some areas of the world is even more drastic. For example, explosives or cyanide are used to stun fish in the coral reefs of some regions. This practice, which wreaks havoc on the whole ecosystem by killing smaller fish and invertebrates, has been fuelled by the demand for live fish in some oriental restaurants.(30) More subtle and general ecological effects of overfishing include impacts on non-target species, on predator/prey relationships, and on genetic diversity; there is no guarantee that all of these changes can be reversed, even if overfishing and environmental destruction are halted.(31) Since 1989, the decline in marine capture fisheries has been largely offset by increased aquaculture production, which grew from 7 million tonnes in 1984 to almost 16 million tonnes in 1993.(32) In view of the evident success of aquaculture and declining wild stocks, policy makers and fisheries managers often see aquaculture as an alternative to capture fisheries as it has the potential to take pressure off wild stocks and also provide economic development opportunities and employment. Ironically, if not practised wisely, aquaculture can actually increase pressure on wild stocks, cause environmental damage (including damage to fish habitat), and affect other of our food supplies. Some concerns focus on potential environmental and ecological risks. For example, crossbreeding between wild stocks and escaped domestic strains of fish could weaken the genetic makeup of wild populations. The risk of disease can be increased in farmed fish cultivated in confined areas and there is the possibility of subsequent transmission to wild stocks. (It should be mentioned that farmed fish are also at risk from diseases that occur naturally in wild stocks.) Fish farming can also result in water contaminated with food and fecal wastes and with the chemicals and drugs used to prevent and treat disease. Fish farming requires suitable areas for development and can therefore destroy habitat important to wild stocks. Cutting down mangroves to provide areas for the construction of fish pens is cited as one of the major reasons for the destruction of as much as half of the world’s mangrove swamps,(33) which, like other wetlands, are important spawning and nursery areas for shrimp and fish. In some areas, "biomass" fishing is now practised.(34) This is the harvesting of small marine fauna, such as krill, to supply feed for fish farms. The effect is twofold: the practice can deplete the food source for other marine life higher up the food chain fish and the catch can include juveniles of commercially valuable species, which can then neither grow to harvestable size nor reproduce. Aquaculture also has social implications. Marine aquaculture requires exclusive rights to coastal lands and access to clean water. In developing countries, fish farms are often owned by foreign companies who displace artisanal fisheries in order to produce high-value products such as shrimp for export to richer countries.(35) Shrimp farming, in particular, is reported to have caused serious problems in a number of developing countries such as Thailand, India, Malaysia and Ecuador, where it has destroyed mangroves, caused water shortages, damaged crops because of seepage of salt water from ponds, and polluted rivers.(36) UNDERLYING CAUSES OF OVERFISHING The industrial, highly mechanized approach to fishing provides both the means and the incentive to overfish. The large capital investment in boats and gear requires a payback, which in turn creates an incentive to maximize fishing effort, leading to a "race to fish." The skipper who is first to the fishing ground with the most efficient boat and gear stands to have the best catches and the highest profit margin. As others improve their boats and gear, staying competitive requires further investment in still faster, more powerful boats, still more efficient gear and so on in a vicious cycle. Those who fish need to catch more fish to pay off their investment but as fish stocks reach their maximum yield they have to fish harder and longer to maintain even the same catch; as a result, operating costs increase and profit margins decline. Ultimately, the fishing is no longer for profit but for survival. Even when constrained by limits such as boat size or the type or size of gear, those who fish have proved remarkably proficient at maximizing their fishing capacity. Any innovation that gives an individual a competitive edge typically spreads rapidly through the fleet, negating the individual advantage but increasing the both harvesting capacity of the fleet as a whole and the capital investment in it. B. Social and Political Factors The fishing industry recently spent $124 billion to land $70-billion worth of fish.(37) Much of the $54-billion shortfall is made up by various forms of subsidies to the fishing industry; intended to stimulate economic activity and create employment, these subsidies are ultimately counterproductive as they undermine the sustainability of the resource. Subsidies are provided not only to the fishing industry but also to shipbuilders. For example, between 1983 and 1990, European Union support for fisheries rose from $80 billion to $580 billion. Much of this support was for the construction of new vessels, modernization of old ones and "exit grants" to encourage the export of redundant vessels to other countries. Spain reportedly provides heavy subsidies to its shipbuilders in order to attract foreign as well as domestic customers.(38) Government’s use of fishing and fish processing to create employment, particularly when other avenues have failed, has given rise to the description of the industry as the "employer of last resort." International aid agencies such as the World Bank and the FAO have also contributed to the expansion of industrial fishing fleets by encouraging developing countries to build such fleets in order to boost foreign exchange earnings.(39) A "ratchet effect" combines social and political pressures with the natural cycles of fish stocks. When stocks are on the upswing, there is a tendency for the industry to expand to take advantage of the boom; on the down phase, there is often strong social and political pressure on governments to provide financial assistance to help the industry survive the lean times in order to protect investment and jobs. The result is that the fishing industry grows beyond the sustainable yield of the resource. Modern fisheries management depends heavily on "scientific" assessment of stocks. In principle, science-based management should permit a more rational and therefore more reliable way of exploiting fish stocks; unfortunately, fisheries science has often proved unequal to the task. This was the case on Canada’s east coast, where overly optimistic stock assessments played a significant role in the collapse of groundfish stocks. In addition to flaws in the methodology of stock assessment, it has been suggested that the process of arriving at total allowable catches (TACs) may have been subject to political manipulation.(40) Even with refinement of fisheries science, the complexity of ecological systems and practical limits to the amount of data that can be gathered will ensure a continuing degree of uncertainty in stock assessments. In the past, fishery managers have often been placed under pressure to allow harvest levels to continue at the upper limits of scientific advice. A report from the British House of Lords says that scientists themselves are partly to blame for the state of the world’s fish stocks for having drawn attention to the uncertainty in their assessments; subsequently, fisheries managers have used this uncertainty to excuse continued overfishing. The report goes on to say that unless scientists deliver clear and forceful advice, governments will continue to sacrifice the long-term sustainability of fish stocks in order to protect short-term jobs in the fishing industry.(41) Continued overfishing and environmental destruction endanger more fish stocks, weaken the long-term economic viability of the fishing industry, undermine the stability of coastal communities, and ultimately threaten the contribution of fishing to the global food supply. The FAO, for example, projects that without a large increase in aquaculture production there will be a potential substantial shortfall of fish and fisheries products by 2010.(42) What should be done? At the most basic level the answer is simple: stop overfishing and protect fish habitat. As Canada’s own experience has demonstrated, however, these imperatives can be remarkably difficult to put into practice. Total fishing effort should be limited to sustainable levels for healthy stocks and reduced for depleted stocks to give them the chance to rebuild to sustainable levels. It has been estimated that about 20 million tonnes could be added to the world’s annual catch if fish populations were allowed to rebuild.(43) The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), for example, recommends that effective recovery plans should be a priority of fisheries managers and stresses that target populations and timetables should be driven primarily by the long-term requirements of fish populations and the marine ecosystem rather than by the short-term demands of the fishing industry.(44) Hence, WWF insists that "fisheries management at all levels must be relieved from sweeping political interference aimed at satisfying the short-term needs of the fishing industry." Unfortunately, the WWF goal may not be too realistic as competition for fishery resources, whether between countries, regions, gear sectors, or user groups, often means that allocation of catches is an inherently political process. Limiting effort to the optimum level, moreover, is much more difficult than it might appear at first glance. In the first place, because of uncertainties in the size of stocks and incomplete knowledge of fish population dynamics, it may not be clear what the limit should be; in the second place, it can be difficult to get an accurate measurement of the true fishing effort. There is also a considerable diversity of opinion on how to limit fishing effort. The WWF recommends that limited-access programs should form part of comprehensive management plans for each fishery. In fact, limited access is already a feature of fisheries management in virtually all developed countries. In Canada, it was introduced in the early 1980s(45) but did not prevent the collapse of the Atlantic groundfish stocks or prevent B.C.’s salmon fishing fleet from growing far beyond the capacity needed to harvest the catch. The means of restricting access can often be controversial. Individual transferable quotas (ITQs), for example, are often seen by larger commercial fishing interests as a way to promote good stewardship of the resource and economic rationalization of the industry since holders of quotas have a vested interest in protecting the resource. ITQs are seen by some as an antidote to the "tragedy of the commons" explanation for the overexploitation of fisheries. On the other hand, ITQs are often resisted by small operations and coastal communities; they see ITQs as a way of privatizing the resource that results in a concentration of quotas in the hands of investors who may have no real attachment to the resource or allegiance to coastal communities. The WWF is critical of measures such as mesh size restrictions and trip limits, describing them as attempts to legislate inefficiency. On the other hand, Safina notes that some regulators have purposefully promoted inefficiency as a way to limit excessive catches and maintain the resource. Examples include laws in the U.S. that require Chesapeake oyster-dredging boats to be powered by sail and the allocation of 52% of the U.S. bluefin tuna quota to the least capable gear: handline and rod and reel. One benefit of the "inefficient" gear is higher employment. In the case of the bluefin tuna, the more labour-intensive gear sector accounts for 80% of direct employment whereas large nets account for only 2%.(46) Sustainability could be improved by reducing bycatches and other incidental damage to juvenile fish and non-target species. In some fisheries, this may mean returning to traditional fishing methods, for example fish traps or the pole and line tuna fishery practised in the 1950s. For other fisheries, it will mean developing and using exclusion devices, such as the Nordmore grate, and more selective gear (such as square, rather than diamond mesh nets). In principle, it might be possible to enhance productivity by fishing down through the food chain rather than by overexploiting the species at the top. In many coastal areas and coral reef systems, fishing effort has already made this shift so that any gains in productivity would have to come from improved management. In open ocean systems, however, it is not currently economic to move down the food chain.(47) Scientific research can provide the basis for sustainable fisheries management. Better understanding of species biology, population dynamics, the interactions of different species, and the effects of climatic and other environmental factors will permit more reliable assessments of stocks and more reliable predictions of the way that stocks are affected by harvesting. In Canada, the collapse of the east coast ground fish fisheries has led to suspicion of science. Because science will nevertheless continue to be an essential management tool, however, it will be important to restore a level of trust among scientists, those who fish, fisheries managers and policy makers. Where reliable scientific advice is not available, a more appropriate strategy may be to return to conservative harvesting methods employing low-technology or passive types of fishing gear which are less able to damage stocks. The fishing industry currently has twice the capacity needed to harvest the sustainable production of the oceans.(48) This results in estimated annual losses of more than US$50 billion and requires a disproportionately high proportion (46%) of the landed value of the catch as a return on capital investment.(49) Improving the economic viability of the fishing industry will require a substantial reduction in the capacity of the world’s commercial fishing industry in order to match sustainable harvest levels. Such a reduction could restore real profitability. For example, a U.S. study found that by reducing the number of boats by 100, profits from the yellowtail fishery could be increased from zero to $6 million annually.(50) Compounding the poor economics caused by overcapacity is the fact that many of the vessels over 100 GRT (and presumably also under 100 GRT) are old and inefficient and, according to the FAO, should be scrapped.(51) Because the old vessels are less efficient, they need to catch more fish to break even (let alone make a profit) and the attempt to do this contributes to overfishing. Stimulating new construction, however, would require an improvement in fisheries economics; thus a "catch-22" situation exists. Reducing fishing fleets will not be easy. It has been suggested that one of the most obvious and effective ways to accomplish this would be to eliminate the subsidies that are responsible for much of the overcapacity in fishing fleets.(52)(53) However, this may not go far enough; governments may have to take more active measures to reduce fishing fleets, though these will create an expectation of compensation that will be difficult for governments to meet. There will also be social and political pressure not to reduce employment and destabilize local economies dependent on the fishing industry. Participation in the fishing industry will, however, have to be reduced to a level that can provide stable and secure incomes within the sustainable limits of the resource. To some extent, the social impacts of capacity reduction may be alleviated by policies that favour labour-intensive over capital-intensive fisheries. In the longer term, management regimes must be established that eliminate incentives to overcapacity and overcapitalization. Depending on the nature of the fishery and social and economic factors, these regimes may involve market-oriented tools such as individual transferable quotas (ITQs) or the promotion of community-based or other co-management schemes. Since 1989, aquaculture production has largely offset the decline in marine capture fisheries and it has the potential to make up an increasingly important percentage of the global food supply, to which it already makes a major contribution.(54) If per capita consumption levels of fish are to be maintained into the year 2010, however, aquaculture production will have to double in the next 15 years.(55) Aquaculture has great potential to increase the production of fish protein, generate economic activity, and provide employment but, as described earlier, it also has the potential to harm capture fisheries and cause social disruption. The growth of aquaculture will therefore have to be carefully managed to ensure that it supplements rather than displaces capture fisheries and that it is based on sound environmental, economic and social principles. Fortunately, there appears to be a growing international consensus supporting conservation of fisheries resources. This section briefly reviews some important, recent international agreements. A. UN Agreement on Straddling Stocks and Highly Migratory Species Foreign overfishing on the Grand Banks has helped drive groundfish stocks to the brink of commercial extinction. As a result, a new convention for the protection of straddling stocks and highly migratory species has been a national priority for Canada, which has been working in the UN since the early 1990s to address the problems of high seas fishing. Agreement was finally reached in New York on 4 December 1995. Signed by 26 member states, the United Nations Agreement on Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks provides: means whereby members of regional fisheries organizations can take enforcement action against vessels fishing the high seas whose flag states are unable or unwilling to exercise control; compatible conservation measures inside and outside the 200-mile limit; a precautionary approach to fishing; and a compulsory and binding dispute settlement mechanism to resolve disputes concerning high seas fisheries. The Agreement will come into force following ratification or accession by 30 UN member states.(56) As of 20 January 1997, 59 states had signed and nine had ratified or acceded to the Agreement. B. FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, approved in Rome in November 1995, is another important step. The code, described as a "comprehensive moral umbrella," applies to marine and fisheries and deals in depth with fisheries management, fisheries operations, aquaculture development, conservation measures, post-harvest practices, trade, and research. The Canadian government, in partnership with industry, is developing a Canadian Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing which will take into account the FAO code but will probably go much further.(57) On 20 May 1994, Canada was the first country to be party to the FAO Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas, which was adopted by the FAO Council in Rome in November 1993. Parties to the FAO Agreement must control fishing on the high seas by vessels flying their flags, in order to ensure that these vessels do not undermine the conservation decisions of international or regional fisheries organizations, even if the Parties are not members of those organizations.(58) In December 1995, 95 states met in Kyoto, Japan, to hold the International Conference on the Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security. The principles of the Kyoto Declaration, if fully implemented, would bring the world’s fisheries much closer to their full potential. These principles include recognition of the importance of fisheries in food security and their social and economic role; steps for the responsible management of fisheries; improvements to food supply through optimum use of harvests and reduction of post-harvest losses; promotion of sustainable and environmentally sound aquaculture; responsible post-harvest use of fish; and ensuring that trade in fish and fishery products does not result in environmental degradation or adversely affect the needs of people for whose health and well-being fish and fishery products are critical. The world’s fisheries have reached, or in many cases even exceeded, the limits of sustainability. At the same time, the world’s population continues to increase by approximately 100 million a year and is expected to surpass 7,000 million by the year 2010. The FAO calculates that maintaining current levels of consumption of fish to the year 2010 will require an additional 19 million tonnes of food fish over the 1993 level of 72 million tonnes.(59) It considers this goal feasible if:

Given all the social, economic and political pressures to keep fishing, together with the environmental effects of fishing and numerous other human activities, this is a daunting challenge and it remains to be seen whether it can be met. The situation also raises the larger question of what happens beyond the year 2010. With the total population of the world projected to rise close to 12,000 million by the end of the twenty-first century,(61) the motivation to keep fishing will be intense. Fishing is a unique activity. It is the only remaining major world industry that exploits a wild resource for food production; however, it is clear that an unfettered industrial approach to fishing is no longer tenable. Without a fundamental shift in outlook at all levels to one that seriously places the conservation of fish and their habitat as the top priority, there is a serious risk that global fish stocks will continue to decline to a much greater extent than has already happened. The consequences for marine ecosystems, the fishing industry, coastal communities, and, not least, the global food supply could be catastrophic. (1) Robert Kunzig, "Twilight of the Cod," Discover, April 1995, p. 52. (2) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, FAO Fisheries Department, Rome 1995, p. 6. (cited hereafter as FAO Fisheries Report) (3) Carl Safina, "The World’s Imperiled Fish," Scientific American, November 1995, p. 49. (4) Fish living on or near the bottom, commonly known as groundfish. (5) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 48. (6) Canada, House of Commons, Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, Evidence, Ottawa, 25 April 1995, 34:26. (7) "Fish: The Tragedy of the Oceans," The Economist, 19 March 1994, p. 22. (8) Mike Hagler, "Deforestation of the Deep," The Ecologist, Vol. 25. No 2/3, March /April, May/June 1995, p. 74. (9) Catherine Stewart, "Newfoundland Collapse: Just the Beginning?" Borealis, Issue 15, p. 38. (10) According to the WWF, a large bluefin that can fetch US$30,000 dockside will fetch US$60,000 at a Tokyo auction. (11) Elizabeth Kemf et. al., Wanted Alive: Marine Fishes in the Wild, World Wildlife Fund for Nature, Gland, Switzerland, 1996, p. 13. (12) Ibid., p. 14. (13) According to Safina (1995), five of the less desirable species made up nearly 30% of the world’s fish catch during the 1980s but accounted for only 6% of the value. (14) Safina (1995), p. 49. (15) Ibid, p. 48. (16) Ibid., p. 50. (17) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 18. (18) Ibid., p. 48. (19) Safina (1995), p. 49. (20) Simon Fairlie et al., "The Politics of Overfishing," The Ecologist, Vol. 25, No. 2/3, March/April May/June 1995, p. 57. (21) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 21. (22) Carl Safina, "Where Have All the Fishes Gone?" Issues in Science and Technology, Spring 1994, p. 40. (23) The discards included 7.7 million kg of halibut, 1.8 million kg of herring, about 200,000 salmon, 360,000 king crabs and 15 million tanner crabs. Kemf et al. (1996), p. 9. (24) Safina (1995), p. 51. (25) Ibid., p. 52. (26) Kemf et al. (1996), p. 9. (27) Ibid., p. 9. (28) Safina (1995), p. 48. (29) Kemf et al. (1996), p. 9. (30) Ibid., p. 10. (31) Hagler (1995), p. 74. (32) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 57. (33) Safina (1995), p. 49. (34) Ibid. (35) Ibid., p. 50. (36) Martin Khor, "A Brutal Hunger for Shrimp," London Free Press, 25 November 1995, p. E4. (37) Safina (1995), p. 50. (38) Fairlie (1995), p. 56. (39) Ibid., p. 50. (40) David Ralph Matthews, "Common versus Open Access: The Collapse of Canada’s East Coast Fishery," The Ecologist, Vol. 25, No. 2/3, March/April, May/June 1995, p. 92. (41) Ehsan Masood, "Scientific Caution ‘Blunts Efforts’ to Conserve Fish Stocks," Nature, 28 February, 1996, p. 481. (42) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 43. (43) Safina (1995), p. 52. (44) Kemf et al. (1996), p. 30. (45) Matthews (1995), p. 88. (46) Safina (1995), p. 53. (47) D. Pauly and V. Christensen, "Primary Production Required to Sustain Global Fisheries," Nature, 16 March 1995, p. 256. (48) Safina (1995), p. 50. (49) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 1. (50) Ibid. (51) Ibid., p. 19. (52) Safina (1995), p. 53. (53) Kemf et al. (1996), p. 30. (54) In 1993, aquaculture accounted for almost 16% of total world fish production but 22% of food production. Source: FAO. (55) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 5. (56) Department of Fisheries and Oceans, "Tobin Addresses UN General Assembly on Fisheries Issues," News Release, 5 December 1995, p. 2. (57) Hon. Fernand Robichaud, Notes for an Address at the The International Conference on the Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security, Kyoto, Japan, 9 December 1995, p. 2. (58) Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Backgrounder, "FAO Compliance Agreement," B-HQ-94-16E, p. 1. (59) FAO Fisheries Report (1995), p. 5. (60) Ibid., p. 5. (61) M.A. El-Badry, "World Population Change: A Long-Range Perspective," Ambio, Vol. 21, No. 1, February 1992, p. 18. |