BP-457E

HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE CONTEXT

OF

Prepared by: TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Democracy, Human Rights and International Instruments WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF

ECONOMIC INTEGRATION GLOBAL MARKETS AND

STRATEGIES FOR PROMOTING A.

Incorporate Human Development and Labour Standards B. Promote

Comprehensive and Enforceable Corporate C. Democratize the Economic Integration Process UPHOLDING HUMAN RIGHTS: WHAT LEGISLATORS CAN DO A. Economic Integration: Linkage Strategies B. The Broader Context: The Promise of Miami 1. Promoting and Protecting Human Rights a. Commitment to

International Conventions and b.

Strengthening the Inter-American Human Rights System c. Strengthening National Programs and Practices d. Oversight for Accountability 2. Addressing Poverty and Discrimination

APPENDIX I: RATIFICATIONS OF SELECTED UN AND

OAS HUMAN RIGHTS CONVENTIONS APPENDIX II: RATIFICATIONS OF SELECTED ILO

HUMAN RIGHTS CONVENTIONS APPENDIX III: PLAN OF ACTION OF THE SUMMIT

OF THE AMERICAS DEMOCRACY

HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE CONTEXT OF The emergence of today’s increasingly global marketplace testifies to unprecedented technological advances in communications, transportation and capital mobility in the post World War II period. Developments in the economic sphere that propel nations toward free or freer trade - whether on a regional, continental or hemispheric basis - have been roughly paralleled in time by the steady expansion, now virtually global in scope, in the articulation of human rights values and principles, and their entrenchment in regional, continental and/or international instruments and declarations.(1) In 1994, Heads of State and Government from 34 of 35 member states of the Organization of American States [OAS](2) and the Chief Executive Officers of some of the world’s largest multinational corporations participated in the Miami Summit of the Americas [the Miami Summit]. The hemispheric objectives endorsed by state leaders included not only economic integration, but also the protection and promotion of human rights as means of strengthening democracy and the eradication of poverty and discrimination.(3) The first part of this paper reflects on human rights promotion and protection in light of the objective of hemispheric economic integration. The discussion proceeds from the general premise that, while economic development may not necessarily be incompatible with human development, it is no guarantee of respect for, or advancement of, human rights.(4) The issue is "not a matter of having to choose between rights and commerce [but] a matter of putting rights on a par with commerce."(5) It therefore becomes necessary to consider what strategies may be potentially relevant to meet this objective. This paper then turns to a consideration of the potential scope for action by legislators within the broad context considered by the Miami Summit, in which economic integration represents but one of the "mutually reinforcing set of commitments"(6) defined as objectives for the hemisphere. A. Democracy, Human Rights and International Instruments Human rights advocates underscore the fact that crucial to a well-functioning democracy is respect for the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights affirmed in internationally recognized human rights instruments. Central among these are the Universal Declaration on Human Rights(7) and two international covenants - the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights(8) [ICCPR] and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights(9) [ICESCR]. Together, these human rights instruments comprise the International Bill of Rights. Virtually all countries in the inter-American system have ratified the covenants. Of specific relevance to the hemisphere is the American Convention on Human Rights.(10) It concentrates mainly on civil and political rights also found in the ICCPR and is binding on the 25 States that have ratified it (refer to Appendix I). Current assessments of the human rights record of the hemisphere point, albeit with cautious optimism, to significant improvements. One observer notes:

The Miami Plan of Action approved at the Americas meeting in Miami emphasized the "great progress ...made in the Hemisphere in the development of human rights concepts and norms"; however, it acknowledged that "serious gaps in implementation remain."(12) This assessment is borne out by the work of the New York-based Freedom House group which quantifies the civil and political human rights records of nations and assigns them a "Freedom Score." In its 1995-96 report Freedom in the World, "fully half of the 35 countries in the hemisphere had lower ratings in 1995-96 than several years earlier [1991-92]. Of the remainder, the majority remained stable, with only 20% overall experiencing an improvement."(13) Challenges to democratic governance in the inter-American system involve, for example, threats to human rights, the rule of law, impunity, drugs, crime, poverty (and its disproportionate effect on indigenous peoples, women and children), and lack of educational opportunities, health care and other social programs.(14) The concepts of human rights and democratization are more than just connected. In fact, the strength and quality of a democracy are revealed ultimately by its respect for the human rights of its citizens. It is only over the past 30 years that countries throughout the Americas have come gradually to embrace democratic ideals. Although most states now hold relatively free and fair elections and have relatively efficient representative institutions (i.e., a legislative branch and bureaucracy), both democracy and human rights are fragile. As the Freedom House findings affirm, elections and pluralism are only part of what constitutes genuine democracy and give no guarantee that human rights violations will cease. To narrow the chasm separating the commitment to respect human rights and effective action, governments in the hemisphere set out in the Miami Plan of Action a series of measures designed to promote and protect human rights as means of "preserving and strengthening the community of democracies of the Americas."(15) They agreed to:

Although the issue was not considered within the context of human rights per se, Heads of State also committed themselves to take steps to "eradicate poverty and discrimination" in the hemisphere. Poverty defines the condition of nearly half of the hemisphere’s population. It inhibits the ability of people to participate fully and equally in economic and political life, an essential element of a democratic system. Poverty and inequality are considered human rights issues in international instruments and human rights doctrine. And extreme material inequality lies at the root of many violations of human rights. Strategies endorsed at the Miami Summit to eradicate poverty and enhance social justice include:(16)

The general agreement among state leaders in Miami to "give serious consideration to adherence to international human rights instruments"(17) is viewed as including adherence to the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,(18) known as the "Protocol of San Salvador." The Protocol affirms, among other things, the right of all peoples in the hemisphere to earn their living by freely chosen work under just, equitable, healthy and safe conditions, to organize and join trade unions, to achieve the highest attainable standard of physical, mental and social health as well as adequate nutrition, and to social security. Only five states in the hemisphere have ratified the Protocol of San Salvador. The Miami Plan of Action of the Summit of the Americas is mostly silent on the role of the labour movement in an economically integrated hemisphere and the means to protect and promote fundamental workers’ rights. WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF

ECONOMIC INTEGRATION The effects of liberalized trade and global markets on the promotion and protection of human rights are the subject of debate in many countries, including Canada. On one side of the question are those who maintain that macro-level economic liberalization fuels social progress, democratic development and respect for human rights. Trade and investment, in the words of Thomas d’Aquino, President and Chief Executive of the Business Council on National Issues, "are powerful catalysts for economic liberalization, democratization and the improvement of domestic economic conditions."(19) Political liberalization, which underlies respect for human rights, is said to be fuelled by free markets and free trade, which bring about improvements in wages, working conditions and employment opportunities. Such conditions, advocates of economic integration assert, foster demands for rights and democracy. A further positive effect of global trade and advances in telecommunications technology is transparency. People around the world are now able to bear witness to repression and abuses of human rights occurring in distant locations, often as events unfold. Nations that violate international human rights norms are vulnerable to criticism, pressure and ostracism by the international community and global business enterprises; this may, it is argued, effect changes in the practices of repressive regimes. On the other side of the debate are those who view global competition as a process that subordinates social justice and human progress to economic development. The exigencies of international competitive pressure lead some labour-intensive transnational corporations to seek the low labour costs -- and corresponding minimal labour standards -- found in developing countries. According to some critics, the conditions that give global business enterprises and countries a comparative advantage in the international competition for new markets and for trade and investment dollars are those that disadvantage workers. Seen from this perspective, liberalized trade "has entailed a ‘race to the bottom’, where both environmental and human rights norms, especially labour standards, are lowered in order to attract competition."(20) There is mounting evidence that the benefits produced by economic integration are unequally distributed. Some conditions associated with liberalized trade regimes are: widening gaps between the wealthy and the poor within countries and between wealthy and poor nations; exploited labour; depressed wages and poor living standards in developing economies; unemployment; deregulation of the environment; violation of human rights; and profound social dislocation due to rapid, unplanned urbanization in modernizing economies. Moreover, the improved economic performance of countries known to violate basic civil and political human rights gives credence to the viewpoint that "growth, in itself, is in no way a guarantee of a greater commitment to fundamental rights and freedoms."(21) Analysts who are critical of the impact of economic integration on human rights are not anti-free traders, nostalgic for the past, or supporters of isolationism or protectionist policies, per se. Rather, their critiques are meant to highlight the urgent need to develop, through democratic means, strategies to "manage" the globalization process.

GLOBAL MARKETS AND

STRATEGIES FOR PROMOTING Because there is no automatic correlation between free trade and human rights, concrete action is needed to move the recognition of the link between trade and rights beyond words. An integrated strategy to promote human rights in the context of economic integration, outlined below, highlights three measures: inclusion in trade agreements of policies promoting social progress in working and living conditions; internationally agreed upon and enforceable codes of conduct for corporations doing business overseas; and democratization of the free trade treaty negotiation process. A. Incorporate

Human Development and Labour Standards In the context of economic development and liberalized trade, labour rights, and more broadly based social development rights, are significant for the lives of workers, both as producers of wealth and as consumers. Integrating social development concerns and labour standards into economic policy and planning was central to the agenda of the 1995 World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen. World leaders came together to focus, for the first time, on the global problems of poverty, unemployment and social integration. To address inequality and insecure labour markets, Heads of State endorsed a people-centered development perspective that views human needs, human rights, social benefits, and quality of life and the development of national and global markets as mutually reinforcing. In this context, the Commitments and Programme of Action agreed to at the Social Development Summit affirmed that economic growth is sustained by a social infrastructure that fosters productive employment opportunities, poverty reduction and social integration.(23) A year later, at the Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization in Singapore, trade ministers affirmed their "commitment to the observance of internationally recognized core labour standards" which include freedom of association and collective bargaining; the prohibition of forced labour, including forced child labour; and non-discrimination.(24) Internationally recognized human rights are included in many ILO human rights conventions specifying basic workers’ rights. With few exceptions, all OAS member states have ratified the majority of ILO human rights conventions (see Appendix II). Despite these various commitments and international safeguards, working and living conditions have not improved in a number of countries currently experiencing economic restructuring and free market growth. To illustrate this point in the context of the western hemisphere, increases in Mexican workers’ wages and improvements in their working conditions have not materialized under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),(25) and "the southern part of the Americas which has the highest per capita income in the developing world ... [also] has the world’s worst record of income distribution."(26) Proponents of linking global economic development and social progress call for, among others, the inclusion of labour standards in international trade liberalization agreements as one means of ensuring that prosperity and justice keep pace with one another, at least for those workers directly affected.(27) B. Promote

Comprehensive and Enforceable Corporate Private sector firms can contribute to the promotion and protection of human rights in the countries in which they operate by adopting standards for good corporate behaviour and refusing to do business with oppressive regimes or sub-contractors who violate human rights. Analysts of economic integration note that it makes good business sense to seek new markets in which political, social and economic policies are predictable and stable. The human rights record of a given country is an indicator of such conditions and one of the factors now voluntarily considered by some transnational corporations in making global investment decisions.(28)

A corporate code of conduct also gives nations an instrument with which to control the behaviour of transnational enterprises operating on their soil. Integrating such a code into a multilateral trade agreement "would formally oblige all member states to require that multinationals respect the established principles in the host country. The code could also specify the internationally recognized labour standards which the corporation must abide by in its operations abroad."(30) Thus, enforceable corporate codes of conduct may advance the protection of human rights by serving as a mechanism whereby corporations can pressure repressive nations seeking investment dollars and nations can pressure corporations that violate core labour standards. C. Democratize the Economic Integration Process The key players in negotiating the terms and conditions of trade agreements in the western hemisphere are government and the business sector. Once countries have signed regional or multilateral free trade agreements, they are bound by rules affecting not only tariffs but a host of legal, social and economic matters once considered the exclusive jurisdiction of national governments and institutions. In the global rush toward economic integration, nation states are surrendering their sovereignty over important policy areas that have consequences for the whole of society. For example:

Because labour and other groups of citizens affected by liberalized trade have been marginalized in the process of economic integration, some see the current framework for bringing about expansion in trade and investment as anti-democratic. Labour advocates in the Americas call for the inclusion in future free trade negotiations of a broad range of civil society interests to ensure that labour, environmental, social and human rights issues are taken into consideration at the drafting stage of international trade treaties.(32) These advocates maintain that greater social participation in free trade negotiations will increase the economic and political viability of integration and decrease social inequality. Such participation is also supported by Canadian economist Sylvia Ostry, a staunch free trader. In a recent interview, she advocated greater input from Canadians and citizens of other countries into the process of negotiating the global rules governing trade. In her opinion, global trade rules -- which are meant to harmonize differences among nations -- have the effect of homogenizing countries. She stated that "I think there should be a public discussion of the whole issue of diversity and where boundaries of sovereignty are."(33) UPHOLDING HUMAN RIGHTS: WHAT LEGISLATORS CAN DO Although the executive branch of government is not the sole guardian of human rights, the related literature appears seldom to focus on the role of legislators in the promotion and protection of these rights. As elected representatives of the people, legislators are uniquely well-situated to evaluate and balance often competing societal interests from a rights perspective and to influence positively the development of human rights public policy both within and beyond their own legal systems. The phrase "rights perspective" here connotes the adoption of a consistent approach to the various dimensions of the legislator’s role, one that has an expansive, proactive and holistic attitude to human rights. The following section discusses avenues by which legislators of the various Parliaments, Congresses and Assemblies of the Americas may exercise their pivotal representative role in the current context. The premise is that accelerated intra-hemispheric relations during and since the Miami Summit have provided legislators with unprecedented opportunities - and, arguably, responsibilities as representatives - to address a broad range of human rights concerns at national and hemispheric levels. The endorsement by Summit participants of a "mutually reinforcing set of commitments" explicitly inclusive of human rights objectives, and incorporating other social, economic and cultural rights dimensions(34) - albeit not under the "rights" heading - suggests that action by legislators need not be confined to human rights matters linked to economic integration processes. This approach is consistent with the affirmation of the 171 nations participating in the 1993 Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, that:

It is thus assumed that proposals relating to rights, in the generic sense, as set out in the Miami Plan of Action, represent the "floor," rather than the "ceiling," of legislators’ potential action on human rights issues. Theoretical and practical considerations are outlined below with the understanding that, because democratization processes and human rights development vary significantly across the hemisphere, not all of them may be universally applicable or relevant in the short term. A. Economic Integration: Linkage Strategies Legislators can be instrumental in keeping human rights concerns central to governments’ economic integration agenda throughout the negotiation process. It is perhaps of special importance that social and economic human rights be kept "on the front burner" in this context. There is a tendency for liberalized trade to affect rights in contradictory ways, so that openings on the civil and political side may be unaccompanied by effective advances in the social and economic sphere.(36) At the national level, their privileged access to legislative and other public fora provides legislators with exceptional advocacy opportunities. These include:

These and similar measures can serve to pressure governments to give substance to what is apparently the sole reference in the Miami Plan of Action to "[securing] the observance and promotion of worker rights, as defined by appropriate international conventions,"(38) in conjunction with the further undertaking, under the Human Rights heading, to seriously consider adherence to unratified international conventions(39) such as the aforementioned ‘Protocol of San Salvador’." In a related vein, legislators can also urge governments to comply with the reporting requests of the International Labour Organization Governing Body on the state of national law and practice in areas covered by ILO conventions, whether ratified or not. Equally or more significant is the legislative role in ensuring that the ratification exercise is more than merely symbolic through enactment at the national level of enforceable implementing legislation containing, at a minimum, employment standards consistent with those instruments.(40) Extra-nationally, legislators also benefit from means to engage in constructive, human rights-oriented exchanges with their peers in the hemisphere on linkage strategies. For instance, a number of trans-national Parliaments of the Americas established with a view to regional integration include human rights promotion and protection among their objectives (these include the Latin American Parliament and the Andean Parliament) and have established a standing committee on human rights (the Central American Parliament) or a working group on Labour Relations, Employment and Social Security (MERCOSUR). The latter model may be of particular interest to legislators advocating linkage, as its agenda includes setting MERCOSUR-wide, guaranteed minimum social provisions.(41) By working through such bodies, legislators can be instrumental in reducing or eliminating regional disparities in respect for human rights, thus creating a more level playing field on which countries of the region can compete.(42) In the process leading to free trade, there is no shortage of issues calling for dialogue, debate and resolution from a rights perspective at domestic and hemispheric levels. In addition to multilateral conditions based on core workers’ rights and corporate codes of conduct, these include: the relevance of making accession to an eventual free trade agreement conditional on either removal of any vestiges of authoritarian rule,(43) or introduction of specified democratic processes; the short- or medium-term feasibility or desirability of developing a hemispheric social charter along the lines of the European Union model,(44) and the merits of creating a specialized hemispheric committee on the social dimensions of trade.(45) The active involvement of elected legislators in promoting human rights interests and broad civil society participation can be influential in determining how these and related issues are ultimately resolved. B. The Broader Context: The Promise of Miami 1. Promoting and Protecting Human Rights In newly emerging or otherwise vulnerable democracies, the exercise of power with the consent of the governed is not always a safeguard of rights, but must be limited by the observance of rights. Declaring that a "democracy is judged by the rights enjoyed by its least influential members," the Miami Plan of Action articulated ambitious objectives aimed at remedying "serious gaps in implementation" of human rights norms. Although not directly linked to economic integration, these objectives are stated as equally integral to charting hemispheric prospects. Noted more fully above,(46) the proposals are aimed, inter alia, at:

The degree to which these goals are translated into effective practice depends largely on ongoing interventions by elected representatives across the hemisphere.

a. Commitment to

International Conventions and Elected representatives can influence building and sustaining a political consensus that centres on respect for international human rights obligations. This approach involves pressing publicly for governments to adhere fully to international human rights norms, not only by ratification, but also through recognition of the competence of human rights adjudication mechanisms, compliance with obligations such as the regular reporting mechanism set out in the ICCPR and ICESCR, and ultimate adoption of corresponding domestic laws. Legislators can also urge greater use of, and fuller governmental cooperation with, human rights oversight and standard-setting bodies such as the UN Commission on Human Rights, whose membership includes over a dozen representatives from American States.

b.

Strengthening the Inter-American Human Rights System The role of legislators in achieving political consensus on the need to respect human rights, and in advocating full adherence to international standards applies even more immediately at the hemispheric level. Ratifications of the American Convention on Human Rights, the inter-American system’s cornerstone instrument, as well as of the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture,(47) are far from complete. Fewer than half of the nations of the Americas have recognized the competence of the Inter-American Court of Justice [IACJ]. The 1988 Protocol of San Salvador has not yet taken effect owing to insufficient ratifications; even fewer nations have ratified more recent instruments relating to the abolition of the death penalty and forced disappearances.(48) Explicit recognition at the Miami Summit that progress in the development of human rights concepts and norms must be accompanied by adequate implementation mechanisms also provides scope for involvement by elected representatives in promoting measures aimed at institutional strengthening of the Inter-American system’s human rights régime. Consisting of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, established in 1959 [IACHR],(49) and the IACJ, established in 1979,(50) the system has been praised for its potential but criticized as lacking in real impact on the human rights situation across the Americas. Ineffective enforcement mechanisms, insufficient resources, prolonged, cumbersome procedures, and lack of cooperation by OAS member states are among factors said to have contributed to this conclusion.(51) In the view of the OAS Secretary General, the "new reality" resulting from increased democratization across the hemisphere has heightened the need to address a number of these factors by introducing concrete measures for additional resource allocation and to fortify the régime’s mandate.(52) Other proposals for enhancing the effectiveness of the inter-American human rights system include establishment of a human rights ombudsperson; creation of a hemispheric Parliament modelled on the proactive European Parliament; fortifying the IACHR’s standard-setting activities; enhancing the autonomy of the IACJ;(53) introduction of a reporting mechanism analogous to those of the ICCPR and ICESCR; and adoption of a mechanism for addressing gross, systematic human rights violations, analogous to the 1991 OAS General Assembly Resolution 1080 on Representative Democracy.(54) Through regional inter-parliamentary exchanges, and in conjunction with government and civil society, legislators can participate in identifying priorities for enhancing the effectiveness of the inter-American human rights system, pressure governments to respond positively to reform proposals, hold them accountable for doing so in light of the Miami Summit commitment, and seek to prevent the work of the IAHCR and the IACJ from being undermined by government, as some fear may be happening.(55) c. Strengthening National Programs and Practices While not directly or fully responsible for the ratification of international and hemispheric human rights instruments, legislators do have immediate involvement in and responsibility for ensuring that national implementing legislation is not only enacted, but conforms in practice and effect to norms set out in those instruments. The Miami Plan of Action mandate to review and strengthen national laws in relation to specified groups and to undertake necessary steps in relation to others with a view to improving their human rights protection(56) speaks directly to this legislative role, but does not limit it to those areas.(57) Additional government commitments to develop programs promoting human rights generally, and to promote a range of women’s equality rights in particular, also provide legislators with opportunities, legislative and other, to expand the national human rights agenda in positive ways. For example, they can work with government to facilitate the establishment of priorities in these areas, as well as seeking to strengthen civil society participation in defining human rights program needs and devising appropriate remedial measures. In addition, the Miami Plan of Action undertaking to engage in hemispheric exchange and cooperation in human rights matters provides a window for legislators to work collaboratively to ensure that prospects for regional cooperation in human rights are realized. Related specific matters offering legislators ongoing scope with respect to human rights but not explicitly or tangentially addressed in the Miami Plan of Action include:

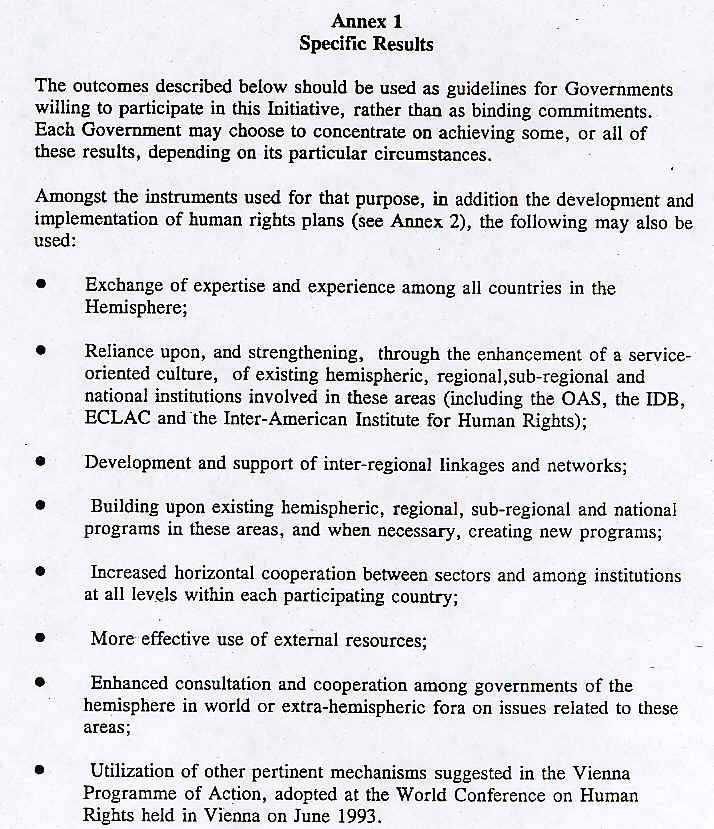

Reform measures with direct implications for elected representatives, largely in the civil and political rights spheres, are integral to a Brazil-Canada Implementation Proposal [the Proposal] for dealing with Miami Plan of Action items in matters of democracy and human rights (see Appendix III).(62) The Proposal currently sets out a flexible framework with a menu of suggested legislative and policy activities aimed at practical achievement of Miami Plan of Action undertakings at the national level. An OAS Working Group on Democracy and Human Rights has a mandate to develop follow-up activities to the Miami Summit, including evaluation of the Proposal.(63) In December 1996, it agreed on administration of justice as an immediate priority for implementation, with the focus on police training, improvement in prison conditions and human rights training for judges and other court officers. Although this process has, thus far, largely involved missions to the OAS at the diplomatic level, elected representatives have a part to play in defining post-Miami human rights programs and in determining whether and how effectively priority programs are carried out. They can, for example, maintain constructive exchanges with the OAS Working Group and other structures promoting human rights within the OAS, such as the Unit for the Promotion of Democracy; work with OAS structures and civil society to identify alternative implementation priorities at national and regional levels; develop contacts with donors active in priority areas;(64) pressure governments to implement priority programs; and monitor their progress and effect in collaboration with civil society. d. Oversight for Accountability The establishment of standing committees with special responsibility for human rights can act as a significant adjunct to other activities for the promotion and protection of these rights. Ideally, such committees enable legislators to exercise important oversight functions that can directly influence the development of national standards. For example, members of the government and their officials can be called to a public committee to justify proposed legislative or other policy measures related to human rights; public hearings can be conducted and reports made on a government's human rights record in general or other governmental activity with human rights implications; governmental action can be recommended and a government response to recommendations can be required. The oversight role can extend to the operation of statutory human rights agencies, regular scrutiny of existing human rights laws for gaps, inappropriate or inadequate processes, and defining priorities for future legislative action related to human rights. In this regard, ongoing consultation with civil society allows committees to keep abreast of new human rights concerns and developments and to better identify the need for legislative reform in specific areas. 2. Addressing Poverty and Discrimination As a closing comment, it is worth noting that, in addition to undertaking to promote and protect human rights in target areas as integral to strengthening hemispheric democracy, the Miami Plan of Action set out the eradication of extreme poverty and discrimination as a separate objective with acknowledged human rights dimensions. International norms in relation to poverty and discrimination have long been entrenched in international conventions, and reiterated in the Declarations and Programmes of Action of more recent international proceedings. Legislators of the hemisphere can work to ensure that the means for achieving the stated objective - defined in part in the Miami Plan of Action as being to provide universal access to primary education and equitable access to basic health services, as well as to strengthen the role of women in society - are developed from a rights perspective, in light of existing international norms. Legislators can collaborate with civil society to identify priorities for reform and to influence the scope and development of government policy in relation to each of these issues, and have a direct role to play in shaping related legislation. Bloomfield, Richard J. "Making the Western Hemisphere Safe for Democracy? The OAS Defense-of-Democracy Regime" (1994), 17 The Washington Quarterly 157. Broadbent, Ed. "Embrace Human Rights in North America Free Trade." Canadian Speeches: Issues of the Day, No. 6, April 1992, p. 41-44. Broadbent, Ed. "Commerce over Conscience? Human Rights and Democracy in the Global Economy." Canadian Speeches: Issues of the Day, No. 8, May 1994, p. 2-7. Broadbent, Ed. "An Action Call to Stop Violations of Human Rights." Canadian Speeches: Issues of the Day, No. 8, November 1994, p. 33-8. Canada, House of Commons, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade. Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence. Issue No. 6. 1st Session, 35th Parliament, 12 April 1994. Canadian Foundation for the Americas (FOCAL). Toward a New World Strategy: Canadian Policy in the Americas Into the Twenty-First Century. Canadian Foundation for the Americas, Ottawa, 1994. de Boer, Elizabeth and Gilbert R. Winham. "Trade Negotiations and Social Charters: The Case of the North American Free Trade Agreement." Canada-U.S. Outlook. Issue on "The Social Charter Implications of the NAFTA." Vol. 3, No. 3, 1992, p. 17. de Wet, Erika. "Labor Standards in the Globalized Economy: The Inclusion of a Social Clause in the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade/World Trade Organization." (1995), 17 Human Rights Quarterly 443. Dias, Clarence and David Gillies. Human Rights, Democracy and Development. International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, Montreal, 1993. Elwell, Christine. "Human Rights, Labour Standards and the New WTO: Opportunities for Linkage - A Canadian Perspective." Essays on Human Rights and Democratic Development No. 4. International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, Montreal, 1995. Farer, Tom J. "Collectively Defending Democracy in a World of Sovereign States: The Western Hemisphere’s Prospect." (1993), 15 Human Rights Quarterly 716. Forcese, Craig. "Commerce with Conscience? Human Rights and Corporate Codes of Conduct." Essays on Human Rights and Democratic Development. International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, Montreal, 1997. Forsythe, David. "Human Rights, the United States and the Organization of American States." (1991), 13 Human Rights Quarterly 66. Frosst, Lynda. "The Evolution of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Reflections of Present and Former Judges." (1992), 14 Human Rights Quarterly 171. Gaviria, Cesar. Secretary General of the Organization of American States. A New Vision of the OAS. Working Document, 1995 (adapted for Internet, available via OAS website, at http://www.oas.org/En/PINFO/nvindexe.htm). Gillies, David. Between Principle and Practice: Human Rights in North-South Relations. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston, 1996. Gillies, David and Gerald J. Schmitz. The Challenge of Democratic Development: Sustaining Democratization in Developing Countries. The North-South Institute, Ottawa, 1992. Gupta, Dipak K., Albert J. Jongman and Alex P. Schmid. "Creating a Composite Index for Assessing Country Performance in the Field of Human Rights: Proposal for a New Methodology." (1993), 15 Human Rights Quarterly 131. International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development. "Globalization, Trade and Human Rights: The Canadian Business Perspective - A Summary Report of the Toronto Conference." 1996 (available via ICHRDD website, at http://www.ichrdd.ca/111/english/contentsEnglish.html). International Labour Organization. The ILO, Standard Setting and Globalization. Report of the Director General to the 85th Session of the International Labour Conference. Geneva, June 1997 (available via the ILO website, at http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc85/dg-ex.htm). Inter-Parliamentary Union. Parliament: Guardian of Human Rights. Report of the Inter-Parliamentary Symposium. Budapest, May 1993. Kilgour, David. "Joint Responsibility: Human Rights Across the Commonwealth." The Parliamentarian, Vol. LXXVII, April 1996, p. 122. Medina, Cecilia. "The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Reflections on a Joint Venture." (1990), 12 Human Rights Quarterly 439. North, Liisa and Yasmine Shamsie (the Canadian Foundation of the Americas), and George Wright (Centre for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean. A Report on Reforming the Organization of American States to Support Democratization in the Hemisphere: A Canadian Perspective. Centre for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean, North York, 1995. Organization of American States. "The Inter-American System for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights" (available via OAS website, at http://www.oas.org/EN/prog/ hrights.htm). Organization of American States. "The Santiago Commitment to Democracy and the Renewal of the Inter-American System." 21st Regular Session, OAS General Assembly, AG/Doc.2734/91, Santiago, 1991(available via OAS website, at http://www.oas.org/EN/ PINFO/RES/resolut.htm). Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Assistance Committee Policy Statements. "Development Partnerships in the New Global Context" (1995). "Conflict, Peace and Development Cooperation on the Threshold of the 21st Century" (1997). (Available via OECD website, at http://cs1-hq.oecd.org/dac/htm/policy.htm). Plan of Action of the Summit of the Americas: Democracy and Human Rights Implementation Proposal, Brazil (coordinator) - Canada (co-coordinator) Initiative, 1995, obtained from Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. Schmitz, Gerald J. and Corinne McDonald. Human Rights, Global Markets: Some Issues and Challenges for Canadian Foreign Policy. Background Paper BP-416E. Parliamentary Research Branch, Ottawa, 1996. Smith, James F. "NAFTA and Human Rights: A Necessary Linkage." (1994), 27 U.C. Davis Law Review 793. Summit of the Americas. Declaration of Principles, "Partnership for Development and Prosperity: Democracy, Free Trade and Sustainable Development in the Americas." Miami, 1994 (available via official Free Trade Area of the Americas website, at http://www.ftaa-alca.org./ministerials/miami_e.asp). Summit of the Americas. Plan of Action. 1994 (available via official FTAA website, at http://www.ftaa-alca.org./ministerials/plan_e.asp). Thede, Nancy. "Democracy and Human Rights in the Hemisphere." Forces. (forthcoming), 1997. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1996 and Human Development Report 1997. Oxford University Press, Cary, North Carolina and Oxford, U.K., 1996 and 1997) (Summaries available via UNDP website, at http://www.undp.org/hdro/index.html).

ENDNOTES 1 The instruments selected are, with the exception of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, suggested for ratification in the Brazil-Canada Implementation Proposal, note 62. The Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, or "Protocol of San Salvador" which is not yet in force in the absence of the required eleven ratifications, is not included on this list. Sources for United Nations instruments: Human Rights: International Instruments - Chart of Ratifications as at 30 June 1996 (United Nations: New York and Geneva, 1996), and the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights website, at http://www.unhchr.ch/html/intlist.htm source for OAS instruments: Organization of American States website, at http://www.cidh.oas.org/basic.htm. 2 American Convention on Human Rights, OAS Treaty Series No. 36. 3 Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, OAS Treaty Series No. 67. 4 International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UNTS, Vol. 993, CTS 1976/46. 5 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UNTS, Vol. 999, CTS 1976/47. 6 Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UNTS, Vol. 999, CTS 1976/47. 7 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, UNTS, Vol. 660. CTS 1970/28. 8 Convention on the Rights of the Child, UN Doc. A/RES/44/25, adopted by general Assembly 20 November 1989, CTS 1992/3. 9 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, UNTS, Vol. 1249, CTS 1982/31. 10 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, UNTS, Vol. 1465, CTS 1987/36.

ENDNOTES 1 Each of the 34 nations of the Americas participating in the Miami Summit is an ILO member. Source for ILO ratifications: Lists of Ratifications by Convention and by country (as at 31 December 1996), (Geneva: International Labour Office, 1997). 2 Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention, 1948 (No. 87), UNTS, Vol. 68, CTS 1973/14. 3 Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98), UNTS, Vol. 96. 4 Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29), UNTS, Vol. 39. 5 Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105), UNTS, Vol. 320, CTS 1960/21. 6 Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111), UNTS, Vol. 362. 7 Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100), UNTS, Vol. 165. CTS 1973/37. 8 Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138), UNTS, Vol. 1015.

* This paper was originally prepared for the Delegation from the Parliament of Canada to the Parliamentary Conference of the Americas, September 1997, Quebec City. (1) In the Americas, for instance, the earliest bilateral or regional trade agreements date from the 1950s, while the inter-American system for the promotion and protection of human rights was formally inaugurated in 1948. (2) Cuba has been excluded from participation in the OAS since 1962. (3) Summit of the Americas, Declaration of Principles, "Partnership for Development and Prosperity: Democracy, Free Trade and Sustainable Development in the Americas" [Miami Declaration] (available via official Free Trade Area of the Americas website, at http://www.ftaa-alca.org./ministerials/miami_e.asp). See also Summit of the Americas Plan of Action [Miami Plan of Action] (available at http://www.ftaa-alca.org./ministerials/plan_e.asp). (4) The 1996 report of the United Nations Development Programme concluded both that "economic growth and equitable human development must move together in the long run, if both are to succeed," and that "there is no automatic link between economic growth and human development - a simple fact, often forgotten by growth advocates": J.G. Speth, UNDP Administrator, "Economic Growth and Equitable Human Development: The Launch of the 1996 Human Development Report," 16 July 1996 Speech to the National Press Club, Washington, D.C. (available via UNDP website, at http://www.undp.org/undp/news/hdr96sp1.htm). See also Policy Statements of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, particularly "Development Partnerships in the New Global Context" (1995) and "Conflict, Peace and Development Co-operation on the Threshold of the 21st Century" (1997) (available via OECD website, at http://cs1-hq.oecd.org/dac/htm/policy.htm). (5) E. Broadbent, former President of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, quoted in D. Kilgour, "Joint Responsibility: Human Rights Across the Commonwealth," The Parliamentarian, Vol. LXXVII, April 1996, p. 122. (6) Miami Declaration (1994). (7) Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly Resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948. (8) United Nations Treaty Series [UNTS], Vol. 999, Canada Treaty Series [CTS] 1976/47. (9) UNTS, Vol. 993, CTS 1976/46. (10) OAS Treaty Series No. 36. (11) N. Thede, "Democracy and Human Rights in the Hemisphere," Forces, September 1997, p. 2. (12) Miami Plan of Action (1994), para. I(2). (13) Thede (1997), p. 3. (14) Government of Canada, "Notes for an Address by the Honourable Christine Stewart, Secretary of State (Latin America and Africa) to the 26th General Assembly of the Organization of American States," Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Panama City, 3 June 1996. (15) Miami Plan of Action (1994), para. I(2). (16) Ibid., para. III(16) - (20). (17) C. Gaviria, Secretary General of the OAS, A New Vision of the OAS, "Defense and Protection of Human Rights" (available via OAS website, at http://www.oas.org/En/PINFO/nvindex.e.htm). (18) OAS Treaty Series No. 69. (19) T. d’Aquino, "Globalization, Social Progress, Democratic Development and Human Rights," Notes for an Address to the Conference on Globalization, Trade and Human Rights: The Canadian Business Perspective, Toronto, 22 February 1996, p. 6 [Toronto Conference]. (20) Briefing Note for Toronto Conference, jointly prepared by The International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development and the Business Council on National Issues, p. 3. (21) D. Bronson and S. Rousseau, Working Paper, Globalization and Workers’ Human Rights in the APEC Region, International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, 26 October 1995, p. 17. (22) Ibid. (23) United Nations, Report of the World Summit for Social Development (doc. A/CONF.166.9, 19 April 1995). (24) World Trade Organization (WTO): Singapore Ministerial Declaration (doc. WT/MIN(96)/DEC, 18 December 1996), para. 4. Cited in The ILO, Standard Setting and Globalization, Report of the Director General to the 85th Session of the International Labour Conference (Geneva: International Labour Office, June 1997) (available via the ILO website, at http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc85/dg-ex.htm). (25) "North American Free Trade Agreement," Foreign Policy in Focus, Interhemispheric Resource Centre and Institute for Policy Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, January 1997, p. 2. (26) C. Elwell, Human Rights, Labour Standards and the New WTO: Opportunities for a Linkage (Montreal: International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, 1995), p. 24. (27) Ibid. (28) Ibid., p. 3. (29) D.K. Gupta, A.J. Jongman and A.P. Schmid, "Creating a Composite Index for Assessing Country Performance in the Field of Human Rights: Proposal for a New Methodology" (1993), 15 Human Rights Quarterly 131, p. 132. (30) Elwell (1995), note 26, p. 27. (31) Thede (1997), note 11, p. 9. (32) Third Trade Union Summit, Declaration of the Workers of the Americas: Democracy, Development and Social Justice in the Americas, 13 May 1997, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. (33) A. Lindgren, "Trade Negotiator Fears Sovereignty at Risk," The Ottawa Citizen, 28 June 1997, A1. (34) Miami Declaration and Plan of Action (1994). (35) Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (doc. A/CONF.157/23, 12 July 1993). Article I, para. 5. See also D. Gillies, Between Principle and Practice: Human Rights in North-South Relations (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), p. 19-20; C. Dias and D. Gillies, Human Rights, Democracy and Development (Montréal: International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, 1993), p. 7; Elwell (1995), note 26, p. 39-40. (36) House of Commons, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, 1st Session, 35th Parliament, 12 April 1994, 6:13-14 (testimony of E. Broadbent). (37) In this regard, the ILO Director General rejects the notion that standard-setting in the context of trade liberalization entails unrealizable standardization of social protection. In his opinion, denying developing countries the temporary advantages resulting from differences in conditions and levels of protection "would be tantamount to denying them a share in the profits of globalization and, by extension, the possibility of subsequent social development." He suggests that the objective is, rather to establish certain common rules of the game for all partners in the multilateral trade system in the form of guarantees of core fundamental rights: ILO (1997), note 24. Thus, it is not the number of standards that are important, but the type: see E. de Wet, "Labor Standards in the Globalized Economy: The Inclusion of a Social Clause in the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade/World Trade Organization" (1995), 17 Human Rights Quarterly 443, p. 453. (38) Miami Plan of Action (1994), para. II(9)(2). Note that none of the 12 Working Groups established by hemispheric Trade Ministers to lay the groundwork for eventual free trade negotiations is directly concerned with workers’ rights or labour relations matters: see "The Belo Horizonte Ministerial Declaration" issued at the close of the Summit of the Americas Third Trade Ministerial Meeting, Belo Horizonte, 16 May 1997 (available via the FTAA website, at http://www.ftaa-alca.org./ministerials/belo_e.asp). (39) Miami Plan of Action (1994), para. I(2). (40) A search of the ILO online database NATLEX shows that many nations of the Americas do have in place legislation referring to the generally acknowledged core labour rights relating to freedom of association and collective bargaining, prevention of forced labour, prohibition of discrimination, and minimum age (available at http://natlex.ilo.org/scripts/natlexcgi.exe?lang=E). It is not clear to what degree the substantive provisions are in fact standard-setting provisions or, if so, what enforcement mechanisms apply. (41) Elwell (1995), note 26, p. 19. (42) J. Smith, "NAFTA and Human Rights: A Necessary Linkage" (1994), 27 U.C. Davis Law Review 793, p. 817-8. (43) During the 1980s, the then European Community [now the European Union] denied admittance to Spain, Portugal and Greece on this basis: see Elwell (1995), note 26, p. 11. In July 1997, Turkey’s renewed bid to join the EU was reportedly denied, in part, owing to its poor human rights record. (44) European Social Charter (revised), ETS No. 163 (1996) (available via Council of Europe website at http://www.coe.fr/eng/legaltxt/e-dh.htm). (45) The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has recommended that the region recognize minimum social conditions for purposes of achieving more equitable trade and competition: see Elwell (1995), note 26, p. 20. (46) Refer to text under heading "Human Rights in the Americas: C. Miami Plan of Action". (47) OAS Treaty Series No. 67. (48) These are the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty, OAS Treaty Series, No. 73, and the Inter-American Convention on the Forced Disappearance of Persons adopted at Belem do Para, Brazil, 9 June 1994. The status of ratifications of OAS instruments is set out at the organization’s website, at http://www.cidh.oas.org/basic.htm. (49) The IACHR derives its authority from two sources: the 1948 OAS Charter (UNTS, Vol. 119) and American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (adopted by the Ninth International Conference of American States in 1948, reprinted in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OEA/SER.L/V/II.71.Doc.6 Rev.1(1987)), under which it exercises collective ombudsperson functions, and the American Convention on Human Rights, note 10, under which it acts as a quasi-judicial body of first recourse. (50) The IACJ was created by the American Convention on Human Rights, with contentious and advisory jurisdiction under prescribed circumstances. (51) The régime’s operation is usefully reviewed and analyzed in C. Medina, "The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Reflections on a Joint Venture" (1990), 12 Human Rights Quarterly 439; D. Forsythe, "Human Rights, The United States and The Organization of American States" (1991), 13 Human Rights Quarterly 66; L. Frosst, "The Evolution of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Reflections of Present and Former Judges" (1992), 14 Human Rights Quarterly 171. (52) See New Vision (1995), note 17, "Defense and Protection of Human Rights." (53) L. North, Y. Shamsie and G. Wright, A Report on Reforming the Organization of American States to Support Democratization in the Hemisphere: A Canadian Perspective (North York: Centre for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean, 1995), p. 44. (54) Adopted at the 21st Regular Session of the OAS General Assembly, Santiago, Chile, 5 June 1991. The OAS response to emergent threats to democracy in Haiti and Peru under the authority of Resolution 1080 has, in fact, drawn criticism: see T. Farer, "Collectively Defending Democracy in a World of Sovereign States: The Western Hemisphere’s Prospect" (1993), 15 Human Rights Quarterly 716, and R. Bloomfield, "Making the Western Hemisphere Safe for Democracy? The OAS Defense-of-Democracy Regime" (1994), 17 The Washington Quarterly 157. (55) North et al. (1995), p. 41-2. (56) Groups targeted in this manner include minority groups, indigenous peoples, people with disabilities, migrant workers, children and prisoners. (57) Consistency of approach, from a rights perspective, suggests that all existing and prospective legislation should be subject to review through a "human rights filtre" in light of international commitments. (58) Proposals for OAS involvement in evaluation and reform of national human rights institutions are set out in New Vision (1995), under the heading "Support for institutions and national policies for the promotion and observance of human rights." Principles developed by the 1991 Workshop on National Institutions and subsequently endorsed by the UN Commission on Human Rights and its General Assembly, known as the "Paris Principles," are of interest as guidelines for the establishment of new human rights institutions and the strengthening of existing bodies: see United Nations Economic and Social Council, E/CN.4/1992/43, p. 46-9. (59) Although a search of a comparative constitutional database for Latin American countries indicates that many fundamental human rights norms have been entrenched in at least some constitutions of the region, constitutionalization in itself offers insufficient protection in the absence of effective enforcement schemes (see Comparative Constitutional Laws (human rights) available online via Political Database of the Americas website, at http://www.georgetown.edu/LatAmerPolitical/ Comparative/comparative. html). (60) In many countries of the Americas, judges are elected by legislative assemblies for relatively brief, fixed terms (see Country Summaries available via Political Database of the Americas website, at http://www.georgetown.edu/LatAmerPolitical/Summary/summary.html). See also 1997 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (available via website of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, at http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu2/hrissues.htm). (61) See document "Issues of Special Concern to the Special Rapporteur" of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary and arbitrary executions to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (available via UNHCHR website, Ibid.). (62) See Plan of Action of the Summit of the Americas: Democracy and Human Rights Implementation Proposal, Brazil (coordinator) - Canada (co-coordinator) Initiative, 1995, obtained from Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The Summit Implementation Review Group established in the wake of the Miami Summit accepted Brazil’s offer to coordinate the Democracy and Human Rights theme, and the willingness of Canada and the OAS to assist. (63) The Proposal is likely to be redrafted in light of comments requested from Miami Summit participants. (64) A number of donors have, for example, been active in Administration of Justice projects, including the Inter-American Development Bank, the National Democratic Institute, the Ford Foundation, and the UNDP. |