|

86-10E

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS

A. Composition of the Balance of Payments B. Evolution of the Balance of Payments Situation C. Statistics Canada Summary of Canada's Balance of International Payments

1.

Highlights (First Quarter 1999 - The Daily, 10 June 1999) Current

Account

BALANCE OF PAYMENTS*

Shifts in the balance of payments accounts are always topical because they reflect the country’s international trading performance and affect the foreign exchange markets. The balance of payments data also affect the perception of our economy on the international scene. The Canadian economy is very open, both in terms of the share of output traded and the amounts of capital which flow in and out of the country. Since Canada has a relatively small population base and limited domestic capital available, it must look to foreign countries, such as the United States, to meet the nation’s capital requirements. The balance of payments therefore takes on special significance. It constitutes a statement of all transactions between Canada and the rest of the world during a given year. The balance of payments also indicates whether or not the country has sufficient foreign currency (or foreign currency earnings) to cover its liabilities to foreign countries. A. Composition of the Balance of Payments The main components of the balance of international payments are:

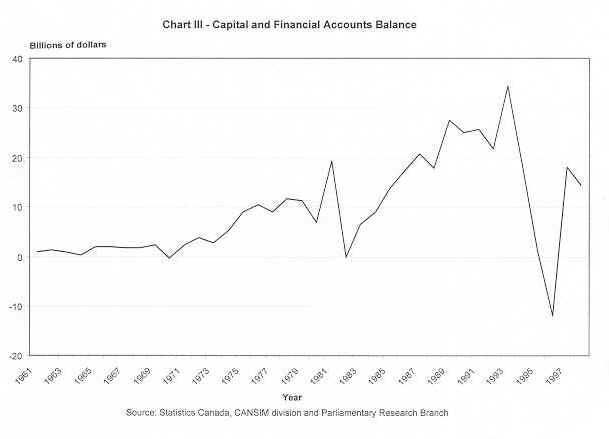

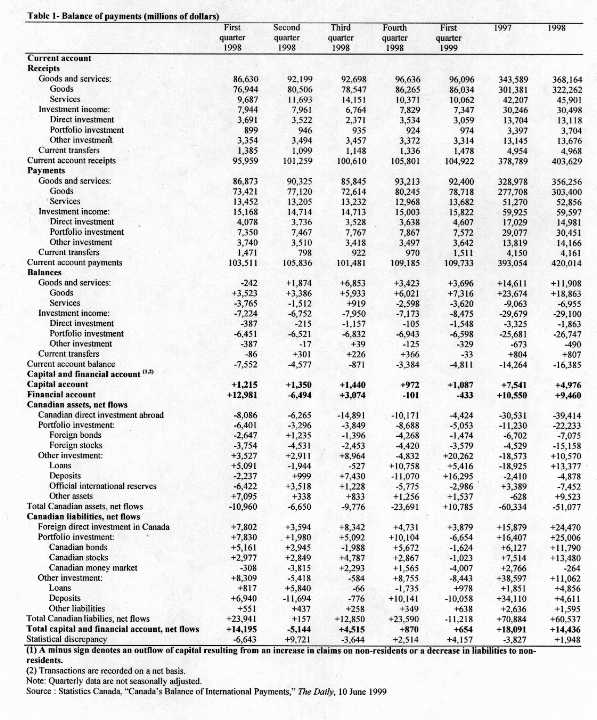

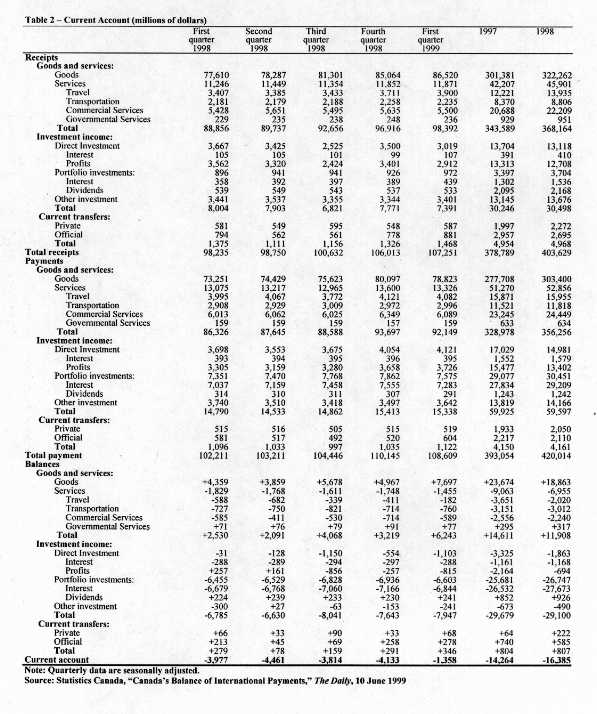

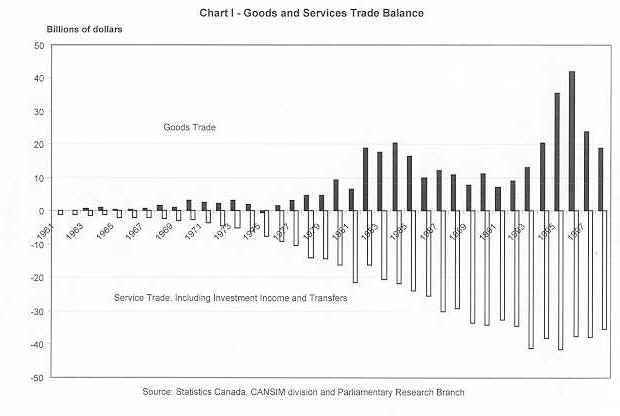

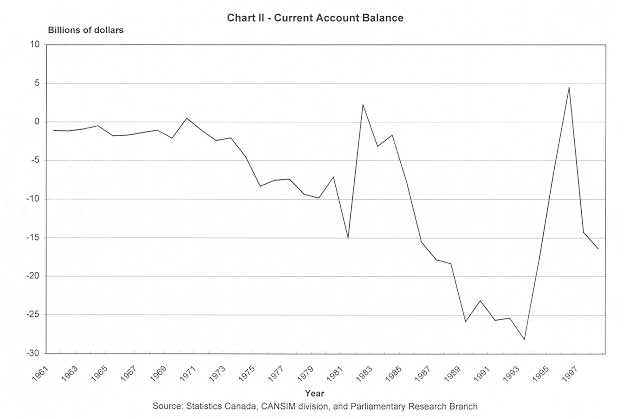

The current account records all receipts and payments from goods and services transactions with foreigners. These transactions are divided into three distinct categories: goods and services, investment income and current transfers. In addition to various goods, "goods and services" includes travel, transportation, commercial services and government services. Investment income includes interest as well as profits and dividends on direct investments, portfolio investments and other investments. Current transfers include payments to individuals and institutions, including pensions, withholding taxes and official contributions, such as Canadian aid to other countries. The current account is affected by several factors. It will post a surplus, or the deficit will shrink, if there is an increase in competitiveness (measured by productivity and relative prices, based on the exchange rate) or if economic growth is less vigorous than in other countries, which would lead to lower import growth. Conversely, an economic decline in foreign countries will negatively affect Canada’s current account balance, as the market for Canadian goods and services shrinks. The capital account is made up of capital transfers, (e.g. migrants’ assets, public service superannuation benefits, debt forgiveness and inheritance funds), and intangible assets (intellectual property rights, such as patents). The financial account records Canada’s financial transactions with foreign countries, including short-term (1 year or less) and long-term movements of capital. There are two types of capital movements: direct investments in the ownership or control of a business and portfolio investments, which are purchases of company stocks and bonds, both public and private. If a foreign resident purchases a Canadian firm or lends money to the government, a credit, identified by a plus sign, will be recorded in the balance of payments accounting process. In contrast, Canadian residents’ purchases of foreign assets are recorded as debits, identified by a minus sign in the balance of payments accounting process. High interest rates in Canada attract foreign capital while encouraging the various levels of government to borrow abroad. Being more speculative in nature, movements of short-term capital exhibit greater sensitivity to short-term interest rates and to exchange rates. The statistical discrepancy (or errors and omissions) resolves divergences between the balances of the current, capital and financial accounts. A deficit on the current account may be exceeded by a surplus on the capital and financial accounts and this will be partially reflected by a build-up of official currency reserves (changes in such reserves are recorded in the financial account). If, however, the net capital inflow is less than the current account deficit, official reserves must be drawn upon. To the extent that fluctuations in official reserves do not equal the difference between the balances of the current, capital and financial accounts, an allowance for errors and omissions must be made. Such discrepancies often reflect movements of short-term capital which have not been captured by the international financial accounting system. Another source of error is illegal shipments, which, of course, are difficult to account for. The world as a whole records a balance of payments deficit which is mathematically and theoretically impossible. It can be explained by timing differences in accounting for goods in transit, and the possibility that some countries record illegal payments from other countries as receipts. In the medium term, the value of the balances of the current, capital and financial accounts should be nearly equal in order to prevent structural imbalance. A balance of payments "deficit" forces Canadian dollars on the international market, placing downward pressure on the domestic currency. Since official reserves for repurchase of such funds are not unlimited, interest rates are typically raised to attract foreign capital and protect the value of the dollar. High interest rates retard economic growth -- lowering import levels -- and the balance of payments difficulties are thus resolved. The costs of excessive interest rates mount over time (being revealed by a growth rate lower than that of comparable industrial nations). Interest rates that are too low relative to other industrial nations make foreign-source capital difficult to obtain; this, too, retards growth. B. Evolution of the Balance of Payments Situation Since the 1950s, the current account has typically been in a deficit position; however, in 1970, 1982 and 1996, it posted a surplus. The trade surplus recorded in 1982 was undoubtedly caused by the recession, which slowed the import of goods and services. During this period, the balance of trade in goods generally posted a surplus, while a substantial deficit persisted in other components of the current account, particularly in services and investment income. The surplus balance in the goods trade and the deficit on services, investment income and transfers have tended to grow since the mid ’70s (see Chart I). The goods trade surplus, which can be attributed largely to exports by the automobile industry as well as energy and forestry products, has usually been overwhelmed by the deficit on services, investment income and transfers, resulting in a deficit on the current account (see Chart II). The deficit on the services, investment income and transfers accounts has usually been caused by large interest payments for outstanding foreign debt. In 1998, the current account deficit rose to $16.4 billion, an increase of $2.1 billion over 1997. During the same year, exports increased by $20.9 billion while imports grew by $25.7 billion. The more rapid growth of imports than of exports resulted in a smaller goods trade surplus in 1998 than in 1997; it declined from $23.7 billion to $18.9 billion. The lower goods trade surplus was partially offset, however, by a decline in the deficit for the other components of the current account. The surplus traditionally posted in the capital and financial account (see Chart III) reflects the continuing need of the Canadian economy (and governments) for foreign capital. In 1998, the capital account posted a $5.0 billion surplus, a considerable drop from the 1997 level of $7.5 billion. The financial account showed a $9.5 billion surplus, a $1.1 billion decline from the 1997 level. Since the early ’80s, portfolio investments in Canada have been notably higher than foreign direct investments in Canada. However, since 1997 the levels of these two types of investment have been similar. International capital flows are separated by Statistics Canada into direct investment and portfolio investment. An investment is classified as direct when it allows the investor to influence the management of an enterprise. An ownership level of at least 10% is assumed to provide this ability. Since 1975, increases in Canadian direct investment abroad have been greater than increases in foreign direct investment in Canada. In 1998, Canadian direct investments abroad amounted to $39.4 billion, while foreign direct investments in Canada amounted to $24.5 billion. Portfolio investments are transactions in bonds and stocks (other than direct investment transactions), official international reserves and foreign investments made by Canadian chartered banks. Net purchases of foreign securities are defined here as total purchases of foreign securities minus total sales of foreign securities. In 1998, net purchases of foreign stocks by Canadians amounted to $15.2 billion, more than three times the 1997 level of $4.5 billion. Foreigners bought Canadian stocks with a total value of $13.5 billion in 1998, up from the $7.5 billion purchased in 1997. Net purchases of Canadian bonds by foreigners totalled $11.8 billion, almost twice the level of the preceding year. In looking at the current account and the financial account we have to review the net fluctuations in the official reserves before calculating errors and omissions. The official reserves level fell by $7.5 billion in 1998, whereas in 1997 it had increased by $3.4 billion. Reserve fluctuations are caused chiefly by the Bank of Canada’s desire to prevent substantial shifts in the value of the Canadian dollar and are included in the financial account. Errors and omissions represented +$1.9 billion in 1998, compared to -$3.8 billion in 1997. As described earlier, one means of compensating for a deficit is to draw down official reserves. Other options open to officials include increasing interest rates in order to attract capital and devaluing the currency to rebalance the current account (this may lead to inflationary pressures). Raising interest rates also tends to restrain domestic aggregate demand, thereby lowering import levels and moving the current account towards balance. Restrictive fiscal measures, by curbing domestic demand, may also serve the same end but at some cost to economic growth and employment levels. In summary:

C. Statistics Canada Summary of Canada's Balance of International Payments 1. Highlights (First Quarter 1999 - The Daily, 10 June 1999) In the first quarter of 1999, the current account deficit sharply declined to $1.4 billion, whereas during the six preceding quarters it had hovered at between $4 billion and $6 billion. This means that, although Canadian residents continued to spend more abroad than they earned from goods, services, investment income and current transfers abroad, they did so at a considerably slower pace. The deficit reduction in the first quarter was largely due to the steady rise in exports, while imports showed the first significant decline since 1996. The net transactions on the financial and capital accounts cancelled each other out in the first quarter. Canadian investors continued to acquire foreign securities, and the federal government increased its international reserves for a second consecutive quarter. There was, however, a reduction in foreigners’ holdings of Canadian securities. As well, the banks engaged in significant transactions which reduced their net deposit assets abroad. 2. Current Account (Seasonally Adjusted) Canada’s surplus on goods expanded strongly, by $2.7 billion to $7.7 billion during the first quarter of 1999. There was a moderate rise in exports with an equivalent decline in imports. This was in contrast to the strong demand for foreign products evidenced in the fourth quarter. Nearly all these changes in exports and imports took place in trade with the United States. Led by a lower deficit on travel, the deficit on services reached an 11-year low of $1.5 billion in the first quarter. The travel deficit moved below $0.2 billion for the first time in over 12 years, mainly due to record spending by visitors from the United States, which increased for the third consecutive quarter. The investment-income deficit edged up to $7.9 billion in the first quarter, however. This modest rise reflected lower profits on Canadian direct investment abroad. 3. Financial Account (Unadjusted for Seasonal Variation) a. Canadian Portfolio Investments Abroad and Foreign-held Canadian Securities Canadian portfolio investment in foreign securities was again substantial at $5.1 billion, but stood at only 60% of the record fourth quarter investment. Most of the acquisition activity, led by mutual funds, was concentrated in foreign stocks. Canadian investors also continued to increase their holdings of foreign bonds, mainly U.S. treasury bonds. After six quarters of increasing their holdings of Canadian debt and equity instruments, foreign investors sold $6.7 billion in Canadian securities. Most of this divestment comprised money market instruments, with the exception of Government of Canada Treasury bills. The decline in the level of foreign investment was largely accounted for by U.S. residents. Canadian stock prices, although up marginally in the quarter, have consistently lagged behind their American counterparts in recent years. Canadian companies continue to invest abroad, although at a considerably slower pace than in the two previous quarters. Canadian direct investment went mainly to the United States and Asia, and was focused on the finance and insurance industry. Foreign companies similarly invested a moderate amount in Canada in the quarter. Acquisitions, which had been the driving force behind record inflows in 1998, were negligible. The direct investment came solely from the United States. Canadian financial institutions, principally banks, channelled a record $16.3 billion back to Canada, more than reversing the substantial outflow of the previous quarter. The reduction in deposit assets in foreign currency abroad reflected mainly those with foreign affiliates, primarily branches located offshore as well as in the United States and Japan. At the same time, the substantial $10.1-billion outflow from Canada was largely made up of foreign currency deposits through Canadian banking affiliates, although one-half of the smaller Canadian currency portion was accounted for by non-affiliated banks. c. Official International Reserves Official international reserves rose for a second consecutive quarter, as the Canadian dollar closed higher against most major foreign currencies. The increase went largely to securities denominated in U.S. dollars, a change from the two previous quarters where the emphasis was on increases in deposits and securities in other denominations. The Bank of Canada is responsible for managing the balance of payments; this responsibility is not handled directly by the government or by Parliament. When interest rates experienced a dramatic rise in 1979, however, the Standing Committee on Finance, Trade and Economy considered the issue. 1964-1981 - Current account deficits, which had increased gradually to $15.0 billion,were replaced by a small surplus in 1970. 1982 - Surplus of $2.3 billion. 1983 - Deficit of $3.1 billion. 1984 - Deficit of $1.7 billion. 1985 - Deficit of $7.8 billion. 1986 - Deficit of $15.5 billion. 1987 - Deficit of $17.8 billion. 1988 - Deficit of $18.3 billion. 1989 - Deficit of $25.8 billion. 1990 - Deficit of $23.1 billion. 1991 - Deficit of $25.6 billion. 1992 - Deficit of $25.4 billion. 1993 - Deficit of $28.1 billion. 1994 - Deficit of $17.7 billion. 1995 - Deficit of $6.1 billion. 1996 - Surplus of $4.5 billion. 1997 - Deficit of $14.3 billion. 1998 - Deficit of $16.4 billion. Capital and Financial Accounts 1964 - 1973 - Apart from a small $0.3-billion surplus in 1964, a small $0.3-billion deficit in 1970, and a $3.8-billion surplus in 1972, the surplus on the financial and capital accounts generally fluctuated around the $2 billion mark. 1974 - 1979 - The surplus increased to more than $11 billion in 1978 and 1979. 1980 - Surplus of $7.0 billion. 1981 - Surplus of $19.4 billion. 1982 - Deficit of $0.027 billion. 1983 - Surplus of $6.5 billion. 1984 - Surplus of $9.0 billion. 1985 - Surplus of $13.7 billion. 1986 - Surplus of $17.4 billion. 1987 - Surplus of $20.9 billion. 1988 - Surplus of $17.8 billion. 1989 - Surplus of $27.6 billion. 1990 - Surplus of $25.2 billion. 1991 - Surplus of $25.8 billion. 1992 - Surplus of $21.9 billion. 1993 - Surplus of $34.5 billion. 1994 - Surplus of $17.8 billion. 1995 - Surplus of $1.3 billion. 1996 - Deficit of $11.8 billion. 1997 - Surplus of $18.1 billion. 1998 - Surplus of $14.4 billion. Bank of Canada. "Canada’s Balance of Payments in the 1970s: A Perspective." Bank of Canada Review, Ottawa, March 1979. Statistics Canada. Canada’s International Investment Position. Publication 67-202 (annual, four-year reporting lag). Statistics Canada. Corporations and Labour Union Returns Act - Part I: Corporations. Publication 61-210 (annual, three-year reporting lag). Contains detailed analysis of foreign ownership control; also breakdown of many professional fees, etc. found in the "other" subaccount of the service section of the current account. Statistics Canada. Quarterly Estimates of the Canadian Balance of International Payments. Publication 67-001 (quarterly, one-quarter reporting lag). Note: All data in the text and following tables are based on the most recent Statistics Canada publication 67-001 available when this review was updated.

* The original version of this Current Issue Review was published in April 1986; the paper has been regularly updated since that time. |