|

PRB 99-4E

EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE:

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS

C. Penalties for Quitting without "Just Cause"

EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE: REGULAR BENEFICIARY TRENDS

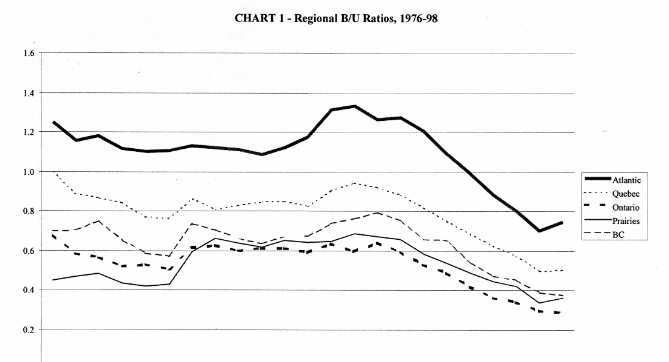

To qualify for regular Employment Insurance (EI) benefits, individuals must, among other things, obtain a minimum number of hours of insurable employment (insurable weeks of employment under the former UI program).(1) Since 1990, relatively fewer unemployed individuals have been able to collect EI benefits, as evidenced by the steady decline in the number of regular EI beneficiaries relative to the number of unemployed (hereafter called the B/U ratio). The following reviews this trend and some of the factors underlying it. The number of regular beneficiaries at any given point in time is a function of many variables, chief among which is the level of unemployment. Between 1976 and 1989, a fairly strong linear relationship existed between the number of regular beneficiaries and total unemployment. Thereafter, this relationship weakened considerably.(2) Chart 1 depicts this relationship in terms of the B/U ratio and illustrates that this trend was common throughout all regions of the country.

Also as illustrated in Chart 1, Atlantic Canada exhibited the highest B/U ratio throughout the entire period 1976 to 1998, followed by Quebec, British Columbia, the Prairies and Ontario. For the most part, the trends for regional B/U ratios were similar throughout this period, although one noteworthy deviation in this regard is the reversal in the position of the Prairies and Ontario following the 1981-82 recession. The B/U ratio in Atlantic Canada witnessed the largest absolute decline between 1976 and 1998, and Ontario exhibited the largest relative decline. Essentially the same holds for the period since 1990, although the Prairies saw a significantly larger relative decline in the B/U ratio in those years than over the entire period. For the nation as a whole, the B/U ratio declined by roughly 50% from 0.83 in 1976 to 0.42 in 1998. This contrasts sharply with the trend in non-regular EI beneficiaries (i.e. employment benefits, special benefits and fishing benefits) expressed as a ratio of the total number of unemployed, which increased from 0.1 to 0.14 throughout the same period. After declining for eight consecutive years, the national B/U ratio increased slightly in 1998. As illustrated in Chart 1, increases in regional B/Us were also registered in Atlantic Canada, Quebec and the Prairies. For many, this trend is worrisome in that EI is providing income replacement to a shrinking proportion of unemployed individuals, something that could have an adverse impact on the program’s stabilization effects and labour market adjustment.(3) In 1997, Human Resources Development Canada initiated a study to identify the factors underlying this trend and explain why proportionately fewer unemployed individuals are claiming regular EI benefits.(4) The B/U report – entitled An Analysis of Employment Insurance Benefit Coverage – was released in October 1998. Data on who receives EI benefits and who does not are collected through a Statistics Canada survey called the Employment Insurance Coverage Survey. This survey was begun in January 1997 and is conducted every three months as part of the Labour Force Survey. In decomposing the B/U ratio, the B/U report builds on previous analytical work that compared "potential beneficiaries," defined as any individuals who could have been eligible for UI/EI between 1972 and 1997,(5) with actual beneficiaries. For example, a voluntary quitter in 1997 with eight weeks of insurable employment in the past year could be a potential beneficiary, since he or she could have been eligible for UI in 1972. The study decomposes changes in the B/U ratio into three parts:

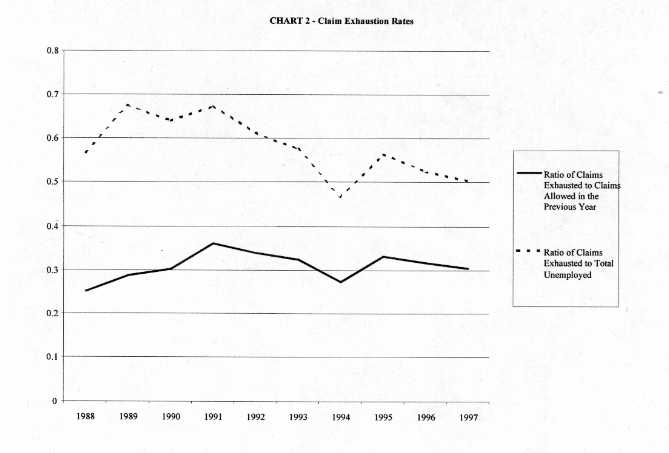

According to this analysis, 48% of the decline in the B/U ratio between 1989 and 1997 is attributed to policy/program-induced changes and 43% to compositional changes in the labour force; the rest is attributed to changes in the ratio of beneficiaries with earnings to unemployment.(6) In terms of labour market effects, the largest was the increase in the proportion of individuals with no employment in the preceding 12 months; their share of total unemployment increased from 20.8% in 1989 to 38.4% in 1997. Slightly more than 25% of this group in 1997 consisted of unemployed individuals with no previous work experience (i.e. new-entrants), while the remaining 75% were unemployed individuals who had had work experience, but not in the previous 12 months. The B/U report states that of the 925,000 unemployed individuals not covered by EI in 1997, 65% consisted of unemployed people with no employment in the last 12 months (483,000 individuals), self-employed and unpaid family workers (65,000 individuals) and unemployed individuals who had left their jobs to attend school (56,000 individuals). None of these three groups (except for self-employed fishers) has ever been covered by Canada’s unemployment insurance system.(7) Growth in this component of Canada’s unemployed population illustrates clearly the inadequacy of the B/U ratio as an indicator of EI coverage.(8) By contrast, 78% (516,000 individuals) of unemployed individuals covered under EI were eligible for EI benefits.(9) According to the B/U report, EI/UI reforms since the beginning of the decade did not appreciably affect the B/U ratio until after 1993, as the recession-induced increase in benefit eligibility and duration offset the policy changes made to the program in the early 1990s. Many of the EI/UI reforms introduced since 1990 were designed to reduce program costs and create incentives to establish stronger attachments to work. As such, these policy changes were designed to reduce the B/U ratio, at least in the short term, while reducing unemployment in the longer term. Throughout this period, three program reforms – modifications to the qualification requirement and to the benefit structure, and the imposition of a total disqualification for quitting a job without "just cause" or losing employment due to misconduct – are thought to have been significant contributors to the reduction in the number of regular beneficiaries. When Bill C-21 was implemented in 1990, the qualification requirement for regular benefits (except those for self-employed fishers) was increased from 10 to 14 weeks of insurable employment (depending on the region) to 10 to 20 weeks. All individuals residing in regions with an unemployment rate below 15% witnessed an increase in their qualification requirement. Qualification requirements were increased by one to five weeks of insurable employment in areas whose unemployment rate was more than 10% but not more than 15%, and by six weeks in all regions whose unemployment rate was below 10%. In 1994, Bill C-17 raised the minimum qualification requirement in the highest unemployment areas of the country from 10 to 12 weeks of insurable employment. In addition, the Unemployment Insurance Regulations were amended so as to impose the same qualification requirement (not qualifying period) on self-employed fishers as on regular claimants. Under the Employment Insurance Act, the most recent change to qualification requirements, the old weeks-based entrance requirement became hours-based (a 35-hour work-week was used to make this conversion). Under this change, the effective qualification requirement increased for those working fewer than 35 hours a week, and decreased for those working more than 35 hours per week. Although EI now extends coverage to the first hour of work, it has also significantly increased the qualification requirement for some part-time workers, particularly those who had qualified under the former program’s minimum insurability rules. New entrants and re-entrants are now required to obtain 910 hours of insurable employment, up 210 hours from the previous hourly equivalent of 700 hours (less under former minimum insurability rules). The new qualification provisions were introduced in two stages. During the latter half of 1996, new entrants and re-entrants were required to obtain six additional weeks of insurable employment in order to qualify for benefits and, as of January 1997, all claimants were subjected to the hours-based qualification requirement. According to the 1997 Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report, the number of new claims (excluding those defined under section 58(1) of the Act) declined by 12% (149,000) between the latter halves of 1995 and 1996 and by 18.6% (169,000) between the first halves of 1996 and 1997. It is interesting to note that claimants with 20 to 25 weeks of insurable employment made up almost one-half of the decline in new claims in the first of these periods and one-third of the decline in new claims in the second.(10) This is the claimant category most affected by the higher qualification requirement for new-entrants and re-entrants. In contrast to this, it seems that some new-entrants and re-entrants have been able to satisfy the new qualification requirement; the number of new claims among those with 26 to 30 weeks of insurable employment increased by 7.5% between the second halves of 1995 and 1996 and 3.5% between the first halves of 1996 and 1997. This is the only claimant category to have registered an increase in new claims during these periods.(11) While the B/U report does not attribute changes in the B/U ratio to specific program reforms, it suggests that failure to meet the qualification requirement was the second most important reason for non-eligibility in 1997, accounting for roughly 142,000 ineligible unemployed EI contributors.(12) Approximately 54% (76,105) of these individuals did not meet the program’s minimum qualification requirement (i.e. 420 hours of insurable employment); while 46% (65,895) met the minimum but could not satisfy the regional qualification requirement. Individuals from Atlantic Canada and youths were more likely to be in the group that failed to meet the minimum qualification requirement than in the group that failed to meet the regional requirement. Compared to the former group, the latter group contained proportionally more men than women.(13) Bill C-21 also collapsed the three-phase benefit structure (i.e. initial, labour force extended and regionally extended benefits) to a single phase. This modification reduced the maximum duration of benefit entitlement in all instances, except for claimants with long employment spells residing in very high unemployment regions of the country. In 1994 (under Bill C-17), claimants witnessed another reduction in maximum benefit entitlement, with the largest effect concentrated in high unemployment regions of the country. For example, claimants with 25 weeks of insurable employment residing in regions with an unemployment rate above 11% and below 15% witnessed a 16-week decline in maximum benefit entitlement. For the country as a whole, average UI entitlement declined from 41 weeks of benefits in the first half of 1994 to 34 weeks in the first half of 1995.(14) The claim exhaustion rates depicted in Chart 2 increased in 1995 and this may explain, in part, the 11% reduction in the B/U ratio in that year.

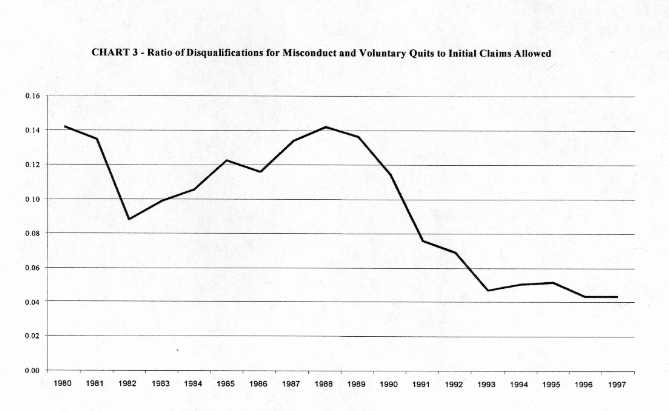

The Employment Insurance Act converted the benefit structure to an hour-based system. Under this reform, the effective benefit entitlement decreased for those working fewer than 35 hours per week, but increased for those working more than 35 hours. In addition, maximum benefit entitlement was reduced from 50 to 45 weeks. The impact of this change was primarily confined to claimants with short-hour work weeks and those who worked at least 1,400 hours or more of insurable employment (long-hour work attachments) and resided in relatively high unemployment areas of the country. For example, under the old system, a claimant in an area with an unemployment rate more than 10% but not more than 11% and who worked 20 hours per week for 30 weeks would have been entitled to 29 weeks of benefits. Today, the same claimant is entitled to a maximum of 22 weeks of benefits. Claimants with long-hour work attachments witnessed as much as a five-week reduction in maximum benefit entitlement depending on the regional unemployment rate. According to the B/U report, 35,000 unemployed individuals who had received or established the right to receive EI benefits exhausted those benefits in 1997. In other words, roughly 3.8% of the unemployed population not covered by EI (i.e. 925,000 unemployed individuals) exhausted their benefits in that year. Compared to other age groups, older individuals (i.e. 45 years of age or more) were most likely to exhaust their benefits. This is not surprising, given that this group witnessed the highest incidence (19.4%) of long-term unemployment (i.e. 53 weeks or longer) that year. The relationship between the regional incidence of exhaustion and long-term unemployment (as defined) is significantly weaker, however; Atlantic Canada registered the highest proportion of exhaustees in 1997 but the second lowest incidence of long-term unemployment. C. Penalties for Quitting without "Just Cause" Prior to 1993, claimants were subjected to a short-term disqualification period, set at between seven to twelve weeks.(15) In 1993, Bill C-113 imposed a total disqualification on individuals who voluntarily left their jobs without "just cause" or who lost their employment due to misconduct. As illustrated in Chart 3, this reform probably had some impact on the B/U ratio as the incidence of disqualification due to voluntary quits and misconduct declined to its lowest level since 1980 and remained relatively stable thereafter.(16) Prior to 1993, a disqualification for misconduct or voluntary quit had a temporary effect on the number of regular beneficiaries throughout the year;(17) however, other things being equal, the 1993 change appears to have permanently reduced the number of regular beneficiaries relative to the number of unemployed in any given month. According to the B/U report, as a result of voluntary quits and employment loss due to misconduct, 100,000 unemployed individuals were not covered by EI benefits in 1997. Voluntarily quitting employment without "just cause" or losing employment due to misconduct is the third most important reason for EI non-coverage. In 1997, this group had relatively higher concentrations of young individuals (i.e. below the age of 35) and individuals residing in the Prairies, where unemployment is low.

While it is too early to tell the ultimate impact of EI reform on the B/U ratio, the cumulative effects of changes to Canada’s unemployment insurance system since the beginning of the decade have undeniably served to lower this ratio. According to the B/U report, program reforms have accounted for as much as one-half of the decline in the B/U ratio since 1990. Changes in the composition of unemployment, especially in terms of the proportion of unemployed individuals who have not worked in the previous 12 months, have also contributed significantly to this trend. The utility of the B/U ratio as a measure of EI benefit coverage has waned in recent years as a result of changes in the composition of the unemployed. In 1997, almost two-thirds of the non-covered unemployed had never been eligible for benefits under Canada’s unemployment insurance system. While the impact of future labour market changes on the B/U ratio is uncertain, the impact of program reforms on that ratio will probably weaken over the longer term, provided, as expected, that these reforms serve to strengthen attachments to work and reduce the overall level of unemployment.(18) (1) The minimum qualification requirement for regular benefits is inversely related to regional unemployment rates. For instance, individuals residing in an area with an unemployment rate that is more than 6% but less than 7% must obtain at least 665 hours of insurable employment to qualify for benefits, whereas individuals residing in an area with an unemployment rate that is more than 13% need at least 420 hours. These qualification requirements are higher for claimants who accumulate one or more "violations" under the Act. Individuals who are defined as new entrants or re-entrants must obtain at least 910 hours of insurable employment to qualify for benefits, irrespective of the regional unemployment rate. According to section 7(4) of the Employment Insurance Act, a new entrant or a re-entrant is one who, in the last 52 weeks before the qualifying period, has fewer than 490 "(a) hours of insurable employment; (b) hours for which benefits were paid or were payable to the person, calculated on the basis of 35 hours for each week of benefits; (c) prescribed hours that relate to employment in the labour force; or (d) hours comprised of any combination of those hours." (2) The relationship between regular beneficiaries and unemployment, as measured by the coefficient of determination, drops from 0.93 (for the period 1976 to 1989) to 0.23 (for the period 1990 to 1998). In other words, 93% of the variation in the number of regular employment insurance beneficiaries is explained by the number of unemployed throughout the period 1976 to 1989, while only 23% is explained by the number of unemployed throughout the period 1990 to 1998. (3) While benefits are intended to raise job search intensity and produce higher re-employment wages and more durable matches between workers and firms, benefits can also adversely influence labour supply decisions and hence the unemployment rate. (4) According to the 1997 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, the B/U study was also supposed to examine the financial impact on those not collecting EI. The B/U report does not address this issue, however. (5) It is estimated that in 1997, 14% of the population of unemployed and out-of-the labour force individuals were potential beneficiaries (Human Resources Development Canada, An Analysis of Employment Insurance Benefit Coverage, W-98-35E, October 1998, p. 29). (6) Human Resources Development Canada, An Analysis of Employment Insurance Benefit Coverage, W-98-35E, October 1998, p. 32. (7) Ibid., p. 46-7. (8) It should also be noted that in 1997 there were 139,000 regular beneficiaries who were not in the labour force (i.e. not counted as unemployed) during the reference week and 94,000 regular beneficiaries who were employed during that week (i.e. not counted as unemployed). (9) Unemployed individuals covered under EI include those who worked in paid insurable employment in the past 12 months and did not leave their employment to go to school or did not quit their jobs voluntarily without "just cause" or lose their employment due to misconduct. (10) The 1997 Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report indicates that between July 1995 to June 1996 and July 1996 to June 1997, the flow of individuals from employment to unemployment declined by about 6% or 40,300 individuals. During the same period, the number of new claims declined by 318,000 or 15%. While the reduction in claims during this period is undoubtedly related to the decline in job loss, this seems to be only part of the explanation. (11) This preliminary result is contrary to that in the impact analysis submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources Development on 23 January 1996. According to that analysis, approximately 90,000 workers would become eligible for benefits as a result of the elimination of minimum insurability criteria and the new hours-based qualification requirement. However, the impact of the hours-based entrance requirement and the higher qualification requirement for new entrants and re-entrants was expected to reduce benefit eligibility by an equal amount. While these qualification-related changes were expected to have an impact on the distribution of claimants, the overall impact on the size of the claimant population was expected to be negligible. (12) Human Resources Development Canada (October 1998), p. 47-8. (13) Ibid., p. 50. (14) Human Resources Development Canada, 1997 Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report, December 1997, Table 7, p. 69. (15) Prior to Bill C-21, implemented in 1990, the disqualification period for voluntarily quitting a job or losing a job due to misconduct was between one and six weeks. (16) The disqualification rate following the 1990-91 recession did not increase significantly as the economy strengthened, a sharp contrast to the pro-cyclical behaviour it exhibited following the 1981-82 recession. (17) For example, during the period 1990 to 1992, claimants disqualified for voluntarily quitting a job or losing a job due to misconduct lost between seven and twelve weeks of benefits. Once this penalty was served, benefits resumed and the B/U ratio rose. This was not the case after April 1993, as claimants disqualified for these reasons were not entitled to benefits at any time during their spell of unemployment. (18) For example, empirical evidence compiled in response to the temporary increase in the entrance requirement in 1990 suggests that some claimants were able to garner the additional weeks of insurable employment to qualify for regular benefits. Between January and November 1990 the variable entrance requirement went from 10 to 14 weeks of insurable employment to a fixed 14 weeks. In response to this, the "spike" in the job-leaving rate at 10 weeks in 1989 moved to 14 weeks in 1990. The higher entrance requirement in 1990 produced an estimated 1.5 weeks increase in the average employment spell and a 0.4 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate in maximum entitlement regions (see D. Green and C. Riddell, Qualifying for Unemployment Insurance: An Empirical Analysis for Canada, Human Resources Development Canada Evaluation Brief No. 1, January 1994). |