|

Library of Parliament |

This document was prepared by the staff of the Parliamentary Research Branch to provide Canadian Parliamentarians with plain language background and analysis of proposed government legislation. Legislative summaries are not government documents. They have no official legal status and do not constitute legal advice or opinion. Please note, the Legislative Summary describes the bill as of the date shown at the beginning of the document. For the latest published version of the bill, please consult the parliamentary internet site at www.parl.gc.ca. |

LS-333E

BILL C-65: AN ACT TO

AMEND THE FEDERAL-

Prepared by: LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF BILL C-65

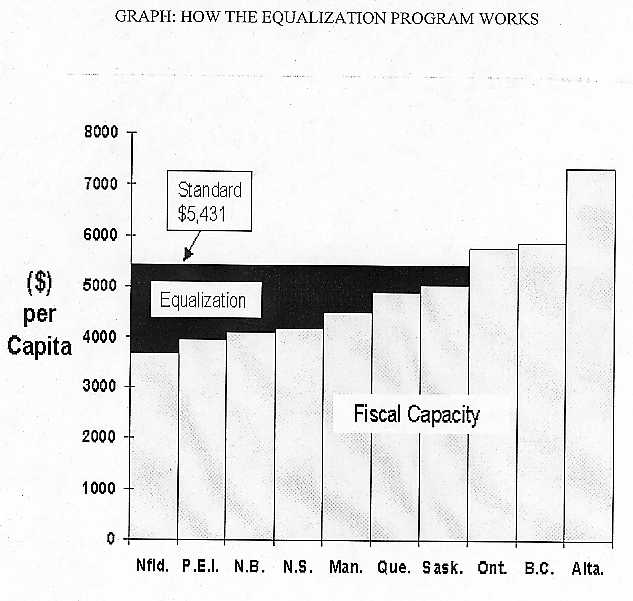

TABLE OF CONTENTS BILL C-65: AN ACT TO AMEND THE FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL Bill C-65, An Act to amend the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act, was tabled in the House of Commons on 2 February 1999. Its purpose is to renew the current Equalization Program, which expires on 31 March 1999, for a further five-year period beginning on 1 April 1999. The Equalization Program is a major federal government transfer program; its purpose is to reduce disparities among the provinces’ revenue-raising abilities, or fiscal capacities. The Equalization Program is the only transfer program enshrined in the Constitution Act (section 36). The federal government’s purpose in redistributing wealth is to allow the less prosperous provinces to provide public services of a quality and at taxation levels comparable to those in other provinces. For example, 1998-99 equalization payments will provide provinces applying the average national tax rate with revenue of $5,431 per capita in order to fund public services (see graph). At present, seven provinces are eligible for equalization payments: Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. These provinces may spend the equalization payments unconditionally in accordance with their own priorities. Equalization payments are calculated according to a formula set out in the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act (the Act). First, each province’s fiscal capacity is calculated by applying an average national tax rate to provincial and local tax bases. Second, provincial fiscal capacities are compared to a representative, composite, standard fiscal capacity based on Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. Third, if a province’s fiscal capacity is lower than the standard, its per capita revenue is raised to the standard by means of equalization payments; if a province’s fiscal capacity is higher than the standard, the province does not receive equalization payments.

Source: Finance Canada, "Minister of Finance Tables Legislation to Renew the Equalization Program," News Release, 2 February 1999 (Internet address http://www.fin.gc.ca/newse99/99-012e.html). Clause 1 of the bill, amending section 3 of the Act, would define a renewed five-year period for the Equalization Program, from 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2004. Clause 2(2) would update the definitions of revenue sources used in calculating provincial fiscal capacities. Two major additions are noteworthy:

In order to lessen the bill’s impact on the provinces, clause 2(1) provides for the new calculation formula to be phased in over four years: for the provinces eligible for equalization payments in 1999-2000, for example, 80% of fiscal capacity would be calculated using the revenue sources as defined on 31 March 1999, and 20% using the newly defined revenue sources. Only starting in 2003 would the provinces’ fiscal capacities be calculated using the new definitions alone. Bill C-65 would also amend the provisions concerning floor and ceiling equalization payments. Clause 2(4), amending section 4(6) and other sections of the Act, would guarantee that an equalization payment to a province could not be lower than the previous year’s payment, less a threshold amount defined in new section 4(7). Clause 2(5), amending section 4(9) of the Act, would prescribe the formula to be used if total equalization payments exceeded a ceiling ($10 billion in 1999-2000), to be adjusted in subsequent years depending on the rate of growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The provision regarding floor equalization payments would protect the provinces against excessive reductions from one year to the next. The provision regarding ceiling equalization payments would protect the federal government from too-rapid growth in equalization payments. Clause 2(6) would make minor amendments to section 4(11) of the Act, in order to solve the problem of taxback. The Act limits excessive taxbacks--large reductions in equalization payments for provinces with concentrated revenues from natural resources. Taxbacks are considered excessive when they are roughly equivalent to provincial revenue increases from particular sources. The Act allows provinces in this situation to choose whether to have the revenue source fully subject to equalization, or to have only 70% of it subject to equalization, but without receiving equalization offset payments under the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Act or the Canada-Newfoundland Atlantic Agreement Implementation Act. In order to offset decreased provincial tax revenues, the Minister of Finance may make stabilization payments to provinces. Clause 3 would make minor changes to this provision in accordance with the new list of revenue sources. Interestingly, Ontario is the province that has benefited most from stabilization payments in recent years. Clause 4 would renew for a further five-year period the agreement on provincial personal income tax revenue guarantee payments. The revenues of provinces that participate in tax collection agreements could be considerably decreased in a given year as a result of federal tax policy amendments; thus the Act provides guarantees in order partially to offset provincial tax revenue reductions. The provinces all support renewal of the Equalization Program. The reason is simple: strong economic growth in Ontario means higher equalization payments to all recipient provinces. Finance Canada anticipates a $700 increase in total equalization payments over the next five years. Saskatchewan (because of the farm income crisis and lower revenues from energy resource extraction fees), the Atlantic provinces (because of weak economic growth), and perhaps even Quebec should receive amounts higher than projected. Saskatchewan would prefer that the new formula not be phased in over four years. This year, Newfoundland will receive $30 million more than projected, an amount that will fully cover its deficit. Equalization payments and transfers under the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) already account for 40% of Newfoundland’s revenues. Against this background of increasing equalization payments, the provinces are not opposed to the newly defined revenue sources either. In his 1997 report, the Auditor General of Canada had pointed out that revenue sources used in calculating provincial fiscal capacities should be corrected to include sales taxes, resources, and lotteries, for example. Bill C-65 and the regulations that will accompany it should correct a number of the discrepancies noted by the Auditor General. Nor are the provinces opposed to including casino revenues in revenue sources, an approach that would increase Ontario’s fiscal capacity and benefit equalization recipient provinces. As well, Quebec and New Brunswick are very satisfied with the new formula for calculating forestry revenues. The old formula expressed forestry revenues in cubic metres of timber cut. Since revenue depends on production value, not production volume (for example, Quebec spruce is worth much less than British Columbia cedar), the old formula overestimated provincial fiscal capacities, something the new formula would correct. Alberta and Saskatchewan are also satisfied with the new classification of certain petroleum deposits. Some locations use expensive extraction methods and thus have lower revenues. The old formula, using the average national tax rate per barrel of oil produced, overestimated provincial revenues. The new formula, by adding another class of petroleum extraction, will no longer overestimate these provinces’ fiscal capacities. However, the bill will not solve some basic problems of the Equalization Program. For example, provincial fiscal capacities are compared with a representative, composite, standard fiscal capacity made up of Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. While increased Ontario fiscal capacity would increase equalization payments, any increased Alberta or Newfoundland fiscal capacity would have no effect on those payments. On the other hand, increased individual income tax rates in Newfoundland would increase equalization payments across Canada, by increasing the average national income tax rate. A number of provinces claim that in making these calculations the federal government should include all the provinces, not just five. Another basic criticism of the Equalization Program persists. As is indicated in a recent study by the C.D. Howe Institute, "income is transferred from poorer Canadians in richer regions to richer Canadians in poorer regions." For example, a poor Vancouver East family (British Columbia) helps provide equalization payments that benefit a rich Westmount family (Quebec). As a result, the federal government should perhaps review the impact of equalization payments on the redistribution of wealth in Canada. Lastly, increased equalization payments will give the federal government less room to manoeuvre, and can be achieved only at the expense of debt paydown, lower taxes, increased program spending on health and social services, or all three. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||