|

Parliamentary Research Branch |

MR-105E CREDIT CARD INNOVATION:

Prepared by Terrence J. Thomas 27 January 1993

TABLE OF CONTENTS CREDIT CARD INNOVATION:

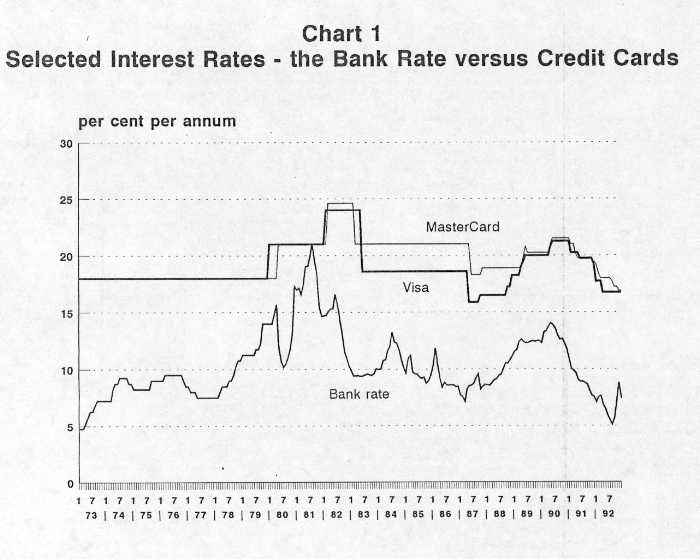

Since the middle of the 1980s, three Parliamentary committees have examined the credit card market in Canada. Although each investigation placed slightly different emphasis on various elements of the credit card market – the extent of competition in 1987, the importance of disclosure in 1989 and the possibility of barriers to entry in 1992 – there has been considerable overlap both in the investigations and the final recommendations. The main focal point in each investigation, moreover, has been the high level of interest rates on credit cards and the tendency of these rates to persist when other interest rates in the economy fall. Members of the three Parliamentary Committees disagreed about the supposed efficiency of the market in setting credit card rates. The 1989 report recommended a cap of 8 percentage points above the Bank Rate for cards issued by financial institutions, while the 1992 report recommended agains using caps, though a minority report stuck by the recommendation of the earlier report. This review examines a recent innovation that reduces the interest rates on available credit cards to well below the cap proposed in 1989. The two charts attached show the movement since the early 1970s of representative bank card rates and the Bank Rate, and the spread betweeen a representative Visa card rate and the Bank Rate. Before 1987, when Parliament began examining the credit card market, changes in the rate on ban cards were infrequent and large (an average change of about 300 basis points); since then, changes have been more frequent and smaller (about 30 basis points). Credit card rates are still very much administered and , unlike the t-bill rate, do not move with day-to-day changes in financial markets. This can be senn in Chart 2, which shows the spread between a representative card rate and the Bank Rate. The spread is not constant, as it would be, subject to some random disturbances, if the credit card rate were a market rate or allowed to be no more than a certain margin above Bank Rate (in which case the ceiling would be likely to become the standard rate). The most important result of the parliamentary investigations may be the recent introduction by several banks of low-interest credit cards. In March 1992, while the Consumer and Corporate Affairs Committee was involved in the third Parliamentary investigation of credit cards, th eBank of Montreal introduced its Prime Plus; in October the Bank of Nova Scotia introduced its Value Visa Card; and in November the Royal Bank introduced its low-interest Visa Card. The following are the terms on the three cards: Bank of Montreal (Prime Plus)

Scotiabank (Value Visa Card)

Royal Bank (low-interest Visa Card)

To use the frame of reference of the proposed cap, the Bank Rate (7.36%) plus an 8 percentage point margin would have equalled 15.36% at the end of 1992. The Bank of Montreal’s prime rate was then 7.25%, so the Prime Plus rate would have been 12.75%. The prime rate for the chartered banks was below Bank Rate – an unusual occurrence – but, even with a more typical relationship, the Prime Plus rate would still have been below 14%. The low-interest cards thus offer a credit card rate below that recommended by the Consumer and Corporate Affairs Committee in 1989. Note, however, that the new low-interest cards charge a relatively high annual fee. Each of the three Committee reports noted that a possible reaction to a cap would be an increase in annual fees, but the recommendation for a cap in 1989 (and the NDP recommendation in 1992) did not extend to the imposition of a consraint on fees or other terms of credit cards. Consumers now have the choice between two types of low-interest cards. One (Prime Plus) offers a floating rate but no grace period; the others (Value Visa and the low-interest Visa card) offer the usual grace period for bank cards and an administered rate that is below the standard bank card rate. The cards with a grace period charge higher annual fees than the card with no grace period. Whether a credit card user should opt for one of the low-interest cards depends on the spending and payment behaviour of that card user. Obviously, if all card users always paid their balance in full each month, the level of interest rate would be irrelevant, as no interest charges would be paid. For those who do not pay in full each month, there is a break-even point at which the low-interest card becomes attractive. The easiest case if for those who never pay in full. For them, the break-even point is where the saving in interest charges equals the increased annual fee for the low-interest card. This break-even point differs from card to card, so the following is a hypothetical calculation that shows the method, but not the exact results, for any of the currently available low-interest cards. Assume regular credit cards chage 17% and a $6 annual fee, while the low-interest card charges 12% and $26 annual fee. What interest-bearing average balance would make savings in interest equal to the $20 increase in annual fees? The answer is $400 (this balance multiplied by the 5 percentage point decrease in the interest rate equals the $20 increase in the annual fee). This calculation ignores the fact that interest charges on bank credit card balances are based on average daily balances; purchases and partial payments during the month change the daily balance and thus the interest charges. The card user who calculates the break-even point on the average remaining balance shown on the monthly statement will have an approximate, and useful, break-even point, but not an exact one. The calculation of a break-even point for those who occasionally pay their balances in full is much more complicated – in large part because the timing of purchases and payments becomes too important to ignore. A rough calculation is possible: take the average monthly balance multiplied by the proportion of the year in which there are interest-bearing balances, and compare this figure to the break-even point. A card user who pays off the full balance in any six of the twelve months each year with an average balance of $800 is right at the break-even point, where the low-interest card becomes attractive; if the average balance were higher or the bill paid off in full less frequently, the low-interest card would save money for the card user. Just as those who always pay on time find the interest rate irrelevant, those who never pay on time find the grace period irrelevant.. For those who occasionally pay their credit card bill in full, low-interest cards with a grace period are more attractive; without a grace period, all credit card purchases bear interest charges from the date of purchase until the bill is paid off in full. An obvious question is whether a card user who could save money with a low-interest card will be able to get one. In the U.S., several banks offer credit cards with rates well below the industry average (12%, in some cases, versus the norm of around 19%), but these banks have strict standards for determining who can get their cards. The Simmons First National Bank card, for example, is known for having one of the lowest interest rates in the U.S., but reportedly about 70% of applicants are rejected. During recent Committee hearings, the Bank of Montreal said that it would use the same criteria for the Prime Plus card as for its ordinary MasterCard. Information from some of the largest credit card issuers suggestes that they approve about 65 to 70% of the applications they receive. This does not mean, however, that they will approve the same proportion of applicants for the low-interest cards. Applicants will probably be those with large outstanding balances, as they have the most to gain from a lowering of the interest rate; however, these card users might also represent the greatest risk, as they are bringing large, unsecured loans to the card issuer. The interest rates on the new cards are in each case below the capped rate proposed in the 1989 report. How other financial institutions will respond to the innovation will depend on the popularity of the low-interest cards with current cardholders. If the innovating card issuers begin to gain market share, the other issuers will promptly fall into line and offer some variant of the new card. Market respoinses, in other words, will drive the credit card market. The new low-interest credit cards are, in one sense, a market response to an obvious problem. In another sense, they are a political response to the activities of the three parliamentary committees, which have successfully changed the behaviour of the card issuers so as to broaden the choices for cardholders. The greatest benefit of the committees’ work may be the low-interest cards. Certainly, any complaint that card rates are too high, or calls for another parliamentary inquiry, can be countered with the question: "Do you have one of the new low-interest cards?"

|