|

BP-335E

ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS

ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

With the elimination of many diseases, particularly those affecting children and the young, Canadians are living longer. The percentage of Canadians over age 65, only 4% in 1900, is now 12% and is expected to increase to 23% within 40 years.(1) This growth in longevity has brought with it a great increase in diseases and disorders that cause dementia,(2) the most common of which is Alzheimer's Disease (AD), first identified in 1906 by Alois Alzheimer,(3) a German neuropathologist. This paper will review some of the major aspects of this dreaded disease and will also discuss the research efforts underway throughout the world to establish the cause(s), develop an effective method of diagnosis, and discover a cure. Alzheimer's disease is a progressive degenerative disorder of the cerebral cortex that produces dementia in middle to late life. Currently no definitive cause has been found for this affliction and no effective treatment has been developed. Clinically, AD results from a progressive loss of neurons from the cerebral cortex and other brain areas. The brain of a person who has died from this disease contains two characteristics: neuritic plaques (clumps of beta-amyloid protein outside the brain cells, or neurons), and neurofibrillary tangles (twisted, spaghetti-like fibres inside damaged neurons). Biochemical abnormalities associated with neuron failure include deposition of amyloid protein in cerebral blood vessels and senile plaques; disrupted nerve-cell-membrane phospholipid metabolism; and decreases in neurotransmitter substances such as acetylcholine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and somatostatin. It is extremely difficult to diagnose this disease without a biopsy, since other conditions, many of which are treatable, can have the same initial symptoms. Two main variants of the disease are known. Early-onset AD, which strikes victims in their 40s and 50s, accounts for only a tiny percentage of AD victims; a subset of this type is hereditary and is known as Familial AD. Late-onset AD, which appears after age 65, is the most common form of the disease. Memory loss is the most prominent early symptom of AD, followed by a slow disintegration of personality and physical control. Total nursing care is necessary in later stages of the disease.

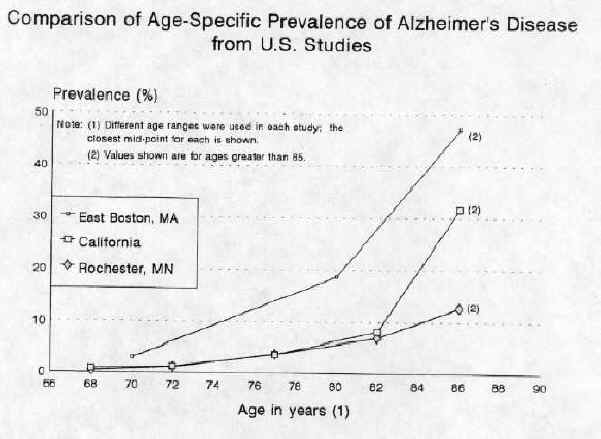

While the disease is progressing, between 10% to 15% of patients hallucinate and suffer delusions, 10% have seizures and 10% will become violent.(5) The change in personality and temperament can be rapid. The rate of progression of the disease varies between patients, with the average time from diagnosis to death being eight years. The family usually cares for a patient at home for an average of four years.(6) This disease frequently masquerades as other ailments. Its diagnosis remains difficult and no simple clinical test has yet been developed. A complete medical team is involved in the evaluation process, which begins with eliminating the other possible causes of such symptoms as impaired intellectual functioning, memory loss, difficulty in recognizing or recalling the names of objects, and impaired ability to distinguish the relationships of objects. The evaluation encompasses medical, neurological and psychiatric examinations, a detailed history of the patient (including a complete inventory of all the drugs he or she takes) and various tests. Once a patient has been diagnosed as having AD, any change in his or her condition must be brought to the attention of the attending physician. The many studies on the incidence of the disease all indicate that this increases immensely in older age groups. The highest incidence was reported in a U.S. survey conducted in East Boston by the Harvard Medical School. It showed the incidence of AD to be 3% for people between the ages of 65-74, 18.7% for those between 75-84, and 47.2% for those over 84.(7) Other studies have shown similar trends (see figure below) but in some cases a much lower overall incidence rate. Although the disease is not of epidemic proportions, the estimated number of Canadians with AD ranges from 300,000(8) to approximately 400,000.(9) With continuous growth in the percentage of Canadians over age 65, this figure could easily exceed 700,000 by the year 2020.

Source: M. Breteler et al., "Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease," Epidemiologic Reviews, Vol. 14, 1992. The human and financial costs of this affliction are enormous. The process of decline takes many years, during the first few of which family members often take care of the patient. Caregivers frequently retire early from paid employment to look after their relative, particularly as the disease progresses. Even when victims are being cared for at home, they frequently require costly medical and other care. The immediate family members, particularly the caregivers, also require help to enable them to cope with this "36-hour-day." The suffering associated with AD is horrendous, as much as for those watching a loved one's slow decline, as for the victims, who may suffer more by being aware of their eventual plight. Since the progression of the disease varies, the rapidity with which victims lose their abilities differs. Even though memory is lost, the relationship between the victim and the family can to some extent be maintained over a period of time, as feelings and emotional responses continue, but as the disease progresses a victim of AD eventually becomes only a "shell." The grief of the victim's immediate family continues, however, though society and friends do not always understand this.(10) Even when using the most conservative estimates of the average number of years spent in an institution, typically three to four years, and the number of afflicted Canadians, the costs to the health care system are immense.

Added to this cost are other major expenses, mainly paid by the public heath care system and social programs, including the support/assistance for the caregiver, the entire medical support team, costly prescription drugs, and modifications to living accommodations. Further cost is incurred if a family caregiver must retire early to care for the victim. Once a patient has been diagnosed as having AD, an assessment is made of the disease's stage of progression and of the strengths and weaknesses of the victim and the victim's family. Several assessment systems are available to evaluate the level of dysfunction in various areas. Based on this assessment, a comprehensive care plan is prepared by a team consisting of a family member, the paid caregiver with primary responsibility for direct care, other care providers, and the victim's physician. Throughout the progression of the disease, and depending on the needs of the patient, a wide range of expensive medication, such as psychoactive drugs to lift depression and sedatives to control violence, may be required. Unfortunately, although a wide range of treatments have been tested, most have proven ineffective. Care at present is mainly palliative. During the initial phases of the disease, the patient can frequently be looked after at home by a caregiver, paid or unpaid, with some social support and medical attention. Simple changes in the home can make life much easier for sufferers, help them maintain self-esteem and a degree of independence, and prolong the period in a home environment. Examples of low-cost changes and modifications to the environment include: reducing the noise levels in the home (noises from television, radio, and telephone as well as from speaking); avoiding vividly patterned and striped rugs, drapes and upholstery; placing locks up high or down low on outside doors and adding simple doorknob alarms; clearing floors of throw rugs and clutter; and reducing the contents of closets to simplify choices. These costs are paid for by the victim's family. Many of these, and other more expensive modifications, are introduced in long-term care settings. They aim at meeting the safety and security needs of the victim, reducing his or her confusion and contributing to the effective functioning of both victims and caregivers. The patient's and the family's condition are assessed every six months. In response to changing needs, the extent and nature of the care are modified, normally in consultation with the family. Other issues that may arise during the care of AD victims are assessment of the victim's competence, power of attorney, and prevention of and response to abuse of both the victim and the caregiver. Eventually the victim's condition deteriorates to the point where home care is no longer possible and he or she must be moved to long-term institutional care. Until an eventual cure and treatment for AD are found, this disease will remain a significant problem for Canadian society. Care, support and information for AD victims and their families come primarily from the health care system and from the Alzheimer's Society, which in Canada is organized at the national, provincial and, frequently, the municipal level. The information and support the society provides are crucial, particularly for the caregivers. The caregiver needs information on the disease, including details of dementia and appropriate methods of care. The victim may become restless, or suspicious, may wander, or have erratic sleep patterns. Such behaviour places an additional strain on the caregiver. Some studies have shown that caregiver depression and inappropriate living arrangements were the factors most associated with violence towards AD victims.(12) The caregivers themselves often suffer from depression or "burnout" and their health deteriorates as a result of trying to help the AD victim. Frequently, conflicts with attitudes and actions of other family members can greatly increase the risk of depression for caregivers. AD support groups offer families the emotional, spiritual and practical help they need to cope with the disease. The caregiver has many needs, including regular and increasingly lengthy relief from duties. The greater the level of support, the longer a caregiver can cope with the patient. The underlying cause(s) of AD remain unknown although theories and ideas abound. Many of the theories, and much of the research, have focused on the beta-amyloid protein, the building block of the plaque found in the brain of AD sufferers. Even the role and toxicity of this protein remain controversial, however, and how it is made and released in the brain is unknown. One of the newest theories on the origin of beta-amyloid was recently reported in the journal Science.(13) It suggests that the beta-amyloid is produced in healthy brain cells and it is its overproduction that creates a problem. Research is continuing on many different approaches to AD and new findings are being reported continually. Some of the suspected causes include:

The actual cause for AD has yet to be established but all or some of the above may be involved. It may well be found that AD is a heterogeneous disorder in which a variety of factors can stimulate the amyloid protein precursor and its derivatives to process aberrantly, so that the beta amyloid protein is released and deposited as amyloid, which then initiates the rest of the pathologic cascade.(25) Several promising new tools are being developed to simplify early diagnosis of AD. Until a cure and a treatment are found, however, early diagnosis can be a mixed blessing, since the knowledge can hurt as much as help. In the past year, several potential methods involving advanced biological testing or the use of sophisticated equipment have been identified. Much more testing will be required before any of these methods is available for general use. A test involving the extraction and analysis of a sample of cerebrospinal fluid for screening for AD at an early stage was announced in August 1992 and is undergoing further testing. The test is based on levels of APP, which in AD victims are as much as 3.5 times lower than normal;(26) the disease appears to progress more quickly, the lower the level of APP. The test can apparently differentiate AD from other forms of dementia and, it is hoped will allow researchers to check the effectiveness of AD treatment. Last summer, the company that developed the test, SIBIA, the corporate spin-off from the Salk Institute of Biotechnology in La Jolla California, said it expected to bring a commercial version to market in late 1993. The status and cost of the test are unknown, but the test would be carried out in a hospital setting. Images from a PET(27) scanner of victims of AD show a reduction in brain activity that is most severe in the parieto-temporal region of the cortex.(28) Unfortunately, only a few specialist hospitals have the equipment needed to exploit this discovery. A promising diagnostic method, normally taking less than 10 minutes, uses a single measurement from a computerised tomography (CT) scan of the temporal medial lobe of the brain. A long-term study found that the measurement of the thinnest point of the lobe was lower for AD sufferers and that there was little overlap between them and the control group. The test could detect 79% of sufferers and reduce the "false positives" to 1%, but an additional test would also be needed to identify all AD victims. Another useful aspect of the test is its ability to distinguish between patients with AD and those with dementia from other causes.(29) Further evaluations are continuing with this approach. Also being investigated is a diagnostic method that uses the results of postmortem studies indicating that an increased choline to N-acetylasparte (NAA) ratio is specific to Alzheimer's disease. The process being developed involves the use of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to "see" the biochemical change in the brain. The testing done so far, which compares the MRS brain images of healthy elderly people with those of young people, rules out the chance that the change in NAA ratio is a function of age. Comparisons between healthy elderly people and elderly people with Alzheimer's disease showed measurable differences.(30) Once the actual cause(s) of the disease are known, it is hoped that a simple test, possibly based on the level of certain key proteins, may become available. Until the definitive cause of AD and the mechanism involved in it are discovered, the disease itself cannot be cured. The current treatment consists mainly of palliative care and maintenance of the patient. Several new developments for treating the symptoms have been announced and further testing and evaluation are needed. The most widely employed strategy for symptomatic treatment of AD is the replacement of neurotransmitters, though few of the trials with various neurotransmitters have been successful. The results of a major trial, conducted on 468 AD patients at 23 treatment centres in 1990 and 1991, was published in November 1992; it confirmed that a 12-week treatment with tacrine hydrochloride provided patients with cognitive improvement.(31) Based on the cognitive component of the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale, the mean response of the 12-week treatment would seem, on average, to reverse six months of the progression, of the disease. The trial also showed that the drug's major side effect, liver toxicity, was reversible. Tacrine, and several other similar drugs, work by inhibiting an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine, which is involved in the memory areas of the brain and is mentioned in the chemical imbalance theory. Several studies show that short-term treatment with selegine, developed for the treatment of Parkinson's Disease and commonly known as L-deprenyl, improved the memory and attention of AD patients.(32) This neurotransmitter inhibits the production of the enzyme monoamine oxidase-B, which is involved in dopamine degradation (the principal defect in Parkinsons's disease) and is thought to cause disturbances to the catecholaminergic system that lead to cognitive defects such as memory loss.(33) New evidence from the Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of Toronto suggests that the drug may bring hitherto unrecognized benefits that compensate for some of the beneficial/nutritive factors lost.(34) Clinical trials and testing are continuing with these and other drugs. Researchers agree that it would preferable to develop drugs to prevent damage rather than simply to boost the effectiveness of one particular neurotransmitter. Some other areas of intervention research/treatment are:

Research into the broader issue of cell death ("apoptosis") may one day provide some help for those suffering from AD. Some very recent discoveries indicate that the bcl-2 gene operates as a blocking agent for cell death without causing cancer.(39) Other research indicates the tantalizing possibility that the bcl-2 gene could be used in fighting neuron death.(40) AD is an enormous social and economic problem. As the population ages, the number of victims will steadily increase, imposing a massive burden on the health care system. Until a cure and an effective treatment are found, AD poses social, legal, and medical challenges as well as problems of scientific policy and resource allocation. Social challenges include ensuring a uniform level of supplemental support for caregivers and optimizing the sharing of resources between expanded home care and institutional care. Legal issues include power of attorney for the victim and voluntary euthanasia, while medical issues include a lack of available institutions for long-term care, particularly specialized units for AD sufferers, and the need for increased education and awareness on the part of the medical community. Another problem is the modest level of funding assigned to AD research in Canada. The Medical Research Council accounts for 80% of neuroscience research; it provided approximately $26.5 million in fiscal year 1992-93 for all neuroscience research, including that on AD.(41) This amount of research is minuscule when compared with the multi-billion dollars spent by Canadian taxpayers to treat the effects of AD. The cause of Alzheimer's Disease remains uncertain, as does the cure. Many researchers are, however, confident that the efforts of both government and the private sector should result in more effective treatment by the end of the century. "Alzheimer's: Is there Hope?" U.S. News and World Report. 12 August 1991, p. 44. "Alzheimer's Pathology Begins to Yield Its Secrets." Science, Vol. 259, 22 January 1993, p. 457. Breteler, Monique M.B. et al. "Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease." Epidemiologic Reviews, Vol. 14, 1992, p. 72. Brown, Phyllida. "Alzheimer's May Not Be Linked To Aluminum." New Scientist, 7 November 1992, p. 16. Brown, Phyllida. "Rescuing Minds from Disease and Decay." New Scientist Supplement, 14 November 1992, p.6. Brown, Phyllida. "Secret Life of the Brain." New Scientist Supplement, 14 November 1992, p. 14. "Cell Death Studies Yield Cancer Clues." Science, Vol. 259, 5 February 1993, p. 760. Davies, Anna. "Capturing Images of Alzheimer's." New Scientist, 17 April 1993, p. 18. "Death Gives Birth to the Nervous System. But How?" Science, 5 February 1993, p. 763. "Doomsday Diagnostic?" Scientific American, August 1992. Eaton, Dr. William. "Unresolved Grief of Family Members of Alzheimer Victims." OANHSS Quarterly, April 1989, p. 5-8. Evans, Denis A. et. al. "Prevalence of Alzheimer's Disease in a Community Population of Older Persons." Journal of American Medical Association, 10 November 1989. Fallow, Marin et al. "A Controlled Trial of Tacrine in Alzheimer's Disease." The Journal of American Medical Association, Vol. 268, No. 18, 11 November 1992. Medical Research Council of Canada. President's Report 1989-1990. p.13. The Merck Manual. Fifteenth Edition. Merck, Sharp and Dohme Research Laboratories, 1987, p. 1323. Murray, Terry. "Protein in Alzheimer's Found in Healthy People." The Medical Post, 6 October 1992, p. 4. Paveza, Gregory J. et al. "Severe Family Violence and Alzheimer's Disease." Gerontologist, August 1992, p. 493-497. Roberts, Garth W. et al. "On the Origin of Alzheimer's Disease: A Hypothesis." Neuroreport, Vol. 4, No. 1, January 1993. Schellengber, Gerard D. et al. "Genetic Linkage Evidence for a Familial Alzheimer's Disease Locus on Chromosome 14." Science, Vol. 25, 23 October 1992, p. 668. Webb, Jeremy. "Brain Scan Gives Fresh Angle on Alzheimer's." New Scientist, 28 November 1992, p. 19. Weber, Susan. "Parkinson's Drug May Benefit Alzheimer's Patients." The Medical Post, 8 September 1992, p. 24. Weber, Susan. "Link between Alzheimer's, Aluminum Questioned." The Medical Post, 24 November 1992, p. 21. Worsnop, Richard L. "Alzheimer's Disease." CQ Researcher, Congressional Quarterly Inc., Vol. 2, No. 27, 24 July 1992, p. 619-639. "Would Decreased Aluminum Ingestion Reduce the Incidence of Alzheimer's Disease?" Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1 October 1991, p. 800. (1) Medical Research Council of Canada, President's Report 1989-1990, p. 13. (2) Dementia is the deterioration of the intellectual, emotional and cognitive faculties to the extent that daily function is impaired. (3) Richard L. Worsnop, "Alzheimer's Disease," CQ Researcher, Congressional Quarterly Inc., Vol. 2, No 27, 24 July 1992, p. 619-639. (4) Ibid., p. 628. (5) "Alzheimer's: Is there Hope?" U.S. News and World Report, 12 August 1991, p. 44. (6) Ibid., p. 45. (7) Denis A. Evans et al.,"Prevalence of Alzheimer's Disease in a Community Population of Older Persons," Journal of American Medical Association, 10 November 1989. (8) "The Time to Act Is Now," A Report on the Workshop on Aging and Mental Health, December 1989, p. 19. (9) Medical Research Council of Canada (1990), p. 13. (10) Dr. William Eaton, "Unresolved Grief of Family Members of Alzheimer Victims," OANHSS Quarterly, April 1989, p. 5-8. (11) "The Time to Act Is Now," Report on the Workshop on Aging and Mental Health, December 1989, p. 19. (12) Gregory J. Paveza, et al.,"Severe Family Violence and Alzheimer's Disease," Gerontologist, August 1992, p. 493-497. (13) "Alzheimer's Pathology Begins to Yield Its Secrets," Science, Vol 259, 22 January 1993, p. 457. (14) "Would Decreased Aluminum Ingestion Reduce the Incidence of Alzheimer's Disease?" Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1 October 1991, p. 800. (15) Susan Weber, "Link between Alzheimer's, Aluminum Questioned," The Medical Post, 24 November 1992, p. 21. (16) Phyllida Brown, "Alzheimer's May Not Be Linked to Aluminum," New Scientist, 7 November 1992, p. 16. (17) Monique M.B. Breteler, et al., "Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease," Epidemiologic Reviews, Volume 14, 1992, p. 72. (18) Worsnop (1992), p. 619-639. (19) Ibid. (20) Each human cell normally has 23 pairs of chromosomes, which consist of coiled DNA(deoxyribonucleic acid) carrying genetic material. (21) Gerard D. Schellengber, et al.,"Genetic Linkage Evidence for a Familial Alzheimer's Disease Locus on Chromosome 14," Science, Vol 25, 23 October 1992, p. 668. (22) Worsnop (1992), p. 619-639. (23) Ibid. (24) Garth W. Roberts et al., "On the Origin of Alzheimer's Disease: A Hypothesis," Neuroreport, Vol. 4, No 1, January 1993. (25) Terry Murray, "Protein in Alzheimer's Found in Healthy People," The Medical Post, 6 October 1992, p. 4. (26) "Doomsday Diagnostic?" Scientific American, August 1992. (27) PET: positron emission tomography (PET) is a research tool using the uptake of tracer amounts of radioisotopes to measure blood flow, glucose, and oxygen metabolism in the living brain. Because of its very high cost and lack of availability, PET currently has little place in clinical diagnosis. The Merck Manual, Fifteenth Edition, Merck, Sharp and Dohme Research Laboratories, 1987, p. 1323. (28) Phyllida Brown, "Rescuing Minds from Disease and Decay," New Scientist Supplement, 14 November 1992, p. 6. (29) Jeremy Webb, "Brain Scan Gives Fresh Angle on Alzheimer's," New Scientist, 28 November 1992, p. 19. (30) Anna Davies, "Capturing Images of Alzheimer's," New Scientist, 17 April 1993, p. 18. (31) Fallow, Marin et al., "A Controlled Trial of Tacrine in Alzheimer's Disease," The Journal of American Medical Association, Vol. 268, No. 18, 11 November 1992. (32) Breteler (1992), p. 59-81. (33) Susan Weber, "Parkinson's Drug May Benefit Alzheimer's Patients," The Medical Post, 8 September 1992, p. 24. (34) Ibid. (35) Ibid., p. 75. (36) Ibid. (37) Gene therapy: modified genetic material is introduced to the body to produce a desired result. This can be done using different vectors, including a retrovirus. (38) Phyllida Brown,"Secret Life of the Brain," New Scientist Supplement, 14 November 1992, p. 14. (39) "Cell Death Studies Yield Cancer Clues," Science, Vol. 259, 5 February 1993, p. 760. (40) "Death Gives Birth to the Nervous System. But How?," Science, 5 February 1993, p. 763. (41) Discussion with N. Morris, Medical Research Council, March 1993. |