|

PRB 98-9E CANADA-COUNCIL OF

EUROPE BEYOND NAFTA TO

A CANADA-EUROPE TRANSATLANTIC Prepared by: TABLE

OF CONTENTS

SUMMARY

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE CANADA’S NAFTA EXPERIENCE (DAY 1) Panel

1 – "Trade Issues and

the Dispute Resolution Mechanisms" CANADA

AND THE EU: TOWARDS A TRANSATLANTIC Session

1 – "Highlights of Canada-Europe

Trade and Economic Relations" APPENDIX – CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE PARLIAMENTARY SEMINAR: PROGRAMME BRIEFING

NOTES FOR CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE DAY

ONE: CANADA'S NAFTA EXPERIENCE PANEL 1: NAFTA TRADE ISSUES AND THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION MECHANISMS NOTE #1: THE NAFTA: ORIGINS, KEY ELEMENTS AND EVOLUTION Origins APPENDIX

1: THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE NAFTA NOTE

#2: THE NAFTA DISPUTE SETTLEMENT PROVISIONS: How

the Dispute Resolution Institutions Work APPENDIX: CHAPTER 19 CASES BETWEEN CANADIAN AND U.S. PARTIES PANEL 2: LABOUR AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS OF NAFTA NOTE

#3: MANDATE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NAFTA'S The

NAAEC and the Commission for Environmental Cooperation NOTE #4: THE NAFTA AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES NAFTA

As a "Green" Agreement? NOTE #5: NAFTA AND LABOUR ISSUES The

Record of NAFTA Institutions APPENDIX: NAALC'S LABOR PRINCIPLES PANEL 3: SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ASPECTS OF NAFTA NOTE #6: NAFTA AND SOCIAL ISSUES From

"Social Dumping" to a "Social Charter"? NOTE #7: NAFTA AND CULTURAL ISSUES The

"Cultural Exemption" within the FTA/NAFTA DAY

TWO: CANADA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION: TOWARDS SESSION

1: HIGHLIGHTS OF CANADA-EUROPE TRADE

SESSION

2: SECTORAL ISSUES AND AREAS FOR FUTURE NOTE

#8: AN OVERVIEW OF CANADA'S CURRENT TRADE IRRITANTS Introduction SESSION

3: BEYOND NAFTA TO A CANADA-EUROPE TRANSATLANTIC NOTE

# 9: STRENGTHENING THE TRANSATLANTIC Introduction APPENDIX

1: EXTRACTS FROM THE 1997 EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION ON EUROPEAN

UNION RELATIONS WITH CANADA

CANADA-COUNCIL

OF EUROPE BEYOND NAFTA TO A CANADA-EUROPE

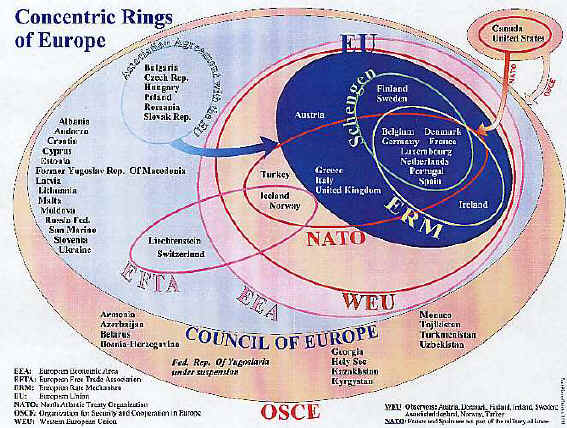

TRANSATLANTIC PREFACE: NAFTA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION In a world of increasingly internationalized economic activity, accompanied by a proliferation of regional trade agreements, the two economic integration blocs that stand out in terms of size and importance are the European economic community and the North American free-trade area. The European Union’s 15 member countries, with a combined population of over 370 million people and GDP approaching US$9 trillion, already constitute an enormous internal market, and one that will grow substantially with the EU’s expected enlargement to over 20 countries. The EU is also the world’s largest exporter of goods and services, and the second largest market for imports. The three countries that are party to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – Canada, the United States, and Mexico – do not constitute a single market and disavow any political integration intentions. Still, the NAFTA area is increasingly integrated in terms of business activity, with corresponding impacts on domestic policy spheres including sensitive matters of environmental, social and cultural regulation. The NAFTA entity is also a potent force internationally, given its market size: almost 400 million people, GDP over US$11 trillion, and internal trade flows of US$500 billion. NAFTA may also expand to include more countries. EU and NAFTA policies have a very large influence on the direction of the global trade and investment regime, which is why it is so important that they be compatible with multilateral principles and the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Systems of regional protectionism would lead to damaging competition. The relationship between the two blocs is therefore also extremely important. As yet, however, from the North American side the economic relationship with Europe has proceeded along primarily bilateral tracks. Both Canada and the U.S. have extensive and recently updated framework agreements with the EU; Mexico is in the process of negotiating its own bilateral trade accord with it. Some concern has been expressed in Canada that the bilateral path risks becoming too much dominated by EU-U.S. priorities, thereby sidelining Canadian interests and values. It has been suggested that a broader transatlantic vision in needed from both the North American and European sides. Whatever the merits of that argument, it seems clear that, just as Canadians can benefit from understanding the implications of economic developments in Europe, Europeans can gain by understanding where Canada is coming from – both in terms of developments within North America and in terms of pursuing transatlantic objectives. In this context a Canada-Council of Europe Parliamentary Seminar was held in Ottawa in October 1998 on the theme "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic Market Place." The following section gives the summary highlights of that seminar. SUMMARY

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE On 19-20 October 1998, the Canadian Parliament hosted a seminar on the theme "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic Marketplace," jointly sponsored by the Canada-Europe Parliamentary Association and the Sub-Committee on International Economic Relations of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly’s Committee on Economic Affairs and Development. The Council, based in Strasbourg, France, is Europe’s oldest body dedicated to the goals of democratic and social solidarity; 1999 marks the 50th anniversary of its founding. Within the Assembly, national parliamentarians from 40 member countries – including all 15 European Union (EU) states and most central and eastern European nations, including Russia – participate in its quarterly sessions, extensive committee work, and associated political-group activities. Canadian parliamentarians have had observer status in the Assembly since May 1997, and have used this to broaden the scope of their involvement in addition to intensifying a longstanding relationship with its economic affairs committee. The idea for the Ottawa seminar was first discussed with the new chair of this committee, Mrs. Helle Degn, during the January 1998 Assembly session. Responding to the initiative from their European counterparts to learn more about the North American free-trade area from a Canadian perspective, Canadian parliamentarians expressed a reciprocal interest that proposed also going beyond the NAFTA to explore further prospects and policy options – in particular, the potential for a broader transatlantic economic arrangement that could connect the increasingly integrated North American and European regional blocs to their mutual benefit. The issues raised by the seminar – notably its concluding session, which considered the possibilities of linking Canadian and European approaches in the context of complex, evolving continental, inter-regional and global trade agendas – have become even more pertinent in the light of the agreement between the United States and the EU reached in November 1998 on a "Transatlantic Economic Partnership" Action Plan. The EU-Canada Summit of 17 December 1998 launched a new "EU-Canada Trade Initiative" but offered few details. In these circumstances, how best can Canada improve its situation alongside its NAFTA partners, while at the same time proceeding towards a closer relationship with European partners? The fourteen panellists who addressed the seminar over its two days (see appendix 1 for the official programme) contributed in different ways to helping formulate an informed response to this question. But the debate also indicated that it will be no easy matter to ensure that Canadian interests are protected and promoted within regional integration and trade negotiation processes, given the other powerful dynamics propelling increased engagement between North America and Europe. The seminar’s first day was devoted to assessments of Canada’s NAFTA experience; specifically, three panels focused on the issues of: trade performance and dispute resolution; environmental and labour mechanisms and impacts; and social and cultural dimensions. In each panel there were three opening presentations, followed by a lively question and discussion period. The Minister of Transport, the Hon. David Collenette, also addressed participants over lunch. The second day moved to consideration of Canada-Europe options for building the transatlantic marketplace. Two morning panels held at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade examined the Canada-EU trade and economic relationship, including some sectoral issues and areas for future bilateral cooperation. As well, the Minister of Industry, the Hon. John Manley, delivered a luncheon address on that theme. The final session attempted to draw some overall conclusions as a basis for advancing the policy agenda in the direction of a broader and deeper Canadian-European trade partnership that will bolster the transatlantic bridge at a time of great international transition and uncertainty. What follows are brief summary highlights from the six panel sessions over the two days of the seminar (the full proceedings will be available as an edited transcript). We have tried to focus on the ideas which are of most interest in terms of promoting a forward-looking Canadian agenda within NAFTA, and beyond that, towards a stronger transatlantic connection with Europe that is fully conscious of the heightened global concerns affecting countries in both regions. CANADA’S NAFTA EXPERIENCE (DAY 1) Panel 1 "Trade Issues and the Dispute Resolution Mechanisms" Speakers:

Michael Hart, who like fellow panellist Gordon Ritchie was closely involved in the negotiation of the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) over a decade ago, began his presentation by underlining the importance of effective dispute resolution as a Canadian trade policy imperative, not only in the bilateral context but also multilaterally. Efforts have been ongoing to strengthen such rules-based mechanisms in order to deal with the challenges of "deeper integration." More is involved than just lowering trade barriers and facilitating cross-border commerce; governments also need better ways to manage relations among themselves and to conciliate varied business, consumer and societal interests. While getting U.S. lawmakers to accept binding international procedures remains extremely difficult, Mr. Hart argued that much progress has been made under the FTA and the NAFTA through the innovative "chapter 19" system of binational panels -- created under FTA and carried over into NAFTA – to resolve anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) cases between the [two] countries. Of the 35 cases litigated under the FTA, the only major exception to this positive track record has been the long-running softwood lumber dispute. As well, rather than talk of "winners" or "losers," Mr. Hart contended that dispute resolution working as it should, not only makes the system more honest, but "has the wonderful benefit of drawing governments back from policies that do not make much sense." Under NAFTA, only 12 of 21 new chapter 19 cases have involved Canada, and there has been only one such case (dealing with supply management in agricultural products) under the chapter 20 general dispute-resolution procedure. The binational system may be tested more often if economic conditions deteriorate. At the same time, we are clearly benefiting from the stronger World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute-settlement regime in place since 1995 (148 consultations involving 112 cases, with 20 final panel decisions to date), which is on the whole "superior to what is in the NAFTA." According to Mr. Hart, the trade-disputes system is working, but also still evolving and open to improvements through future negotiations among member governments. As cases multiply and the issues become increasingly complex, much can also be learned from the European Union (EU) experience with a permanent court that is able to provide more stability and confidence than the ad hoc panels in NAFTA. Sally Rutherford agreed with the assessment that on the whole FTA/NAFTA dispute-resolution mechanisms have served Canada well, for example in sectors like agriculture which have continued to be subject to cross-border harassment. Given that the panel system at least provides for a process that is more rational and less driven by political pressures, it has "significantly increased the confidence of the industry both in primary production and in the processing industry." The FTA was the key breakthrough in that regard; NAFTA added little to it. Despite this advance, Ms. Rutherford described examples from the recent annals of Canada-US agricultural trade to illustrate how the political, and administrative trade-law systems on each side of the border sometimes clash. Such problems not only persist, but may increase as the inter-governmental regulatory environment becomes more complex and at more levels -- e.g., different rules governing sanitary or biotechnology issues in food products at the subnational (state/provincial), federal, and in the case of the EU, supranational levels. NAFTA has worked to minimize harassment, but when disputes "go beyond traditional or historical legal or commercial problems, we have yet to see where that fits in." A further difficulty for affected Canadian industries is the growing expenses, for which American lobbies can marshall more resources, which are now associated with litigating complicated cases. The third panellist, Gordon Ritchie, cautioned that how Canada-U.S. dispute resolution has worked in practice reveals some "serious problems" with its functioning. While it would be unfair to judge the system on the basis of its failure to solve the contentious softwood lumber case, that case is significant as being the biggest, longest-running, and still dominant bilateral trade dispute. Unfortunately, the U.S. has steadfastly refused to dismantle its offensive trade-remedies system. Under FTA/NAFTA rules it is, however, at least obliged to apply its own law fairly. That is a significant improvement, but it should not be expected to do more than restrain considerations of national self-interest. Even with added WTO rules in place, U.S. domestic operating practice often belies that country’s international commitments. In the ongoing lumber dispute, Canada was simply lucky to win a crucial panel decision that split 3-2 on national lines, and subsequent protectionist truces can provide at best temporary relief. (For more details on this context see background Note #2 in the seminar documentation prepared by the Parliamentary Research Branch.) A second key issue raised by Mr. Ritchie was NAFTA’s innovation with respect to investment-related disputes, specifically provisions which allow U.S. corporations – on their own, without requiring the sanction of the U.S, government -- to pursue arbitral procedures against Canadian government authorities alleging violations of their NAFTA rights. Ironically, this can give a foreign company operating in Canada a recourse which would not be available to a Canadian company. Several recent NAFTA investor-state cases brought against Canada have provoked controversy, especially given that similarly flawed provisions "have been bootlegged into proposals for so-called multilateral accords on investment." (Again, for additional details on this context and connection to the ill-fated MAI negotiations, see background Note # 4.) In the discussion period, Mr. Terry Davis (United Kingdom) led off by inquiring about the state of public support for or opposition to North American free trade. Panel co-chair, Senator Sharon Carstairs, and other Canadian parliamentarians present from different parties explained that it had been a highly emotional political issue; indeed a dominant one during the 1988 election campaign when the government was re-elected; public opinion polls had revealed majority opposition to the original FTA though with important regional differences. Labour unions and also certain provinces have led opposition to the trade deals. (For a comprehensive history of this opposition see Jeffrey Ayres, Defying Conventional Wisdom: Political Movements and Popular Contention Against North American Free Trade, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1998.) Over the course of this decade, public attitudes in Canada on free trade seem to have become more relaxed and generally supportive. However, Mr. Ritchie observed that, going beyond NAFTA, some very big issues, such as culture and trade, remain unresolved, notably between Canada and the United States. Anticipating the discussion in the afternoon panel, he argued that Canada must be very firm in defending its values as a nation in such areas. This cultural divide, and the need for Canadians to work with European colleagues to address it multilaterally, was strongly reinforced by panel co-chair M.P. Bill Graham (who chairs the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade which in 1999 will be conducting a major study of prospective global trade negotiations). Joining the discussion, Mr. Hart underlined the added dimensions being brought to bear by "the new political economy of international trade negotiations" in which there are more players than ever before. Not only governments and business interests are involved, but a widening spectrum of civil-society actors, thereby linking the evolving trade and investment agendas to environmental, social, human rights, and other normative objectives. The experience of the MAI illustrates that it is no longer possible to ignore these concerns. Reinforcing that point, Mrs. Durrieu (France) elaborated further on the reasons for France’s withdrawal from the MAI talks which had been scheduled to resume that very day in Paris. Ms. Rutherford observed pointedly that we have entered a period of globalization in which major issues of sovereignty, governance, and coherence among proliferating international agreements remain outstanding, and with unforeseen consequences. Summing up their thoughts on developments beyond NAFTA, other panellists agreed that important policy challenges lie ahead. Mr. Ritchie raised the question of improving the distribution of benefits from trade liberalization, and also the prospect of adding a "North Atlantic configuration" to North American free trade. Mr. Hart envisaged a continuation of disputes over bilateral issues such as lumber, but was optimistic about a progressive interaction of experimentation and consolidation through plural regional and multilateral negotiating arenas. However, he was sceptical about the potential for achieving substantive trade liberalization results in the separate contexts of the proposed "Free Trade Area of the Americas," APEC, or an emerging Transatlantic free-trade area (TAFTA). In his view, a process of multilateral consolidation (i.e., moving matters up to the WTO level) is more likely, driven by the very logic of the major issues now under consideration. On the future of that multilateral trade agenda, Mr. Hart concluded:

Panel 2 "Labour and Environmental Aspects of NAFTA" Speakers:

Jeanine Ferretti began by explaining her agency’s origin, subsequent to the NAFTA agreement being reached, as being part of a further response by the three governments to concerns that NAFTA – even with the inclusion of some "green" provisions – could lead to a worsening of environmental conditions, weakening of environmental regulation, and erosion of public accountability. The environmental "side accord" which created the CEC affirmed three principal objectives: avoidance of trade and environment disputes; effective enforcement of environmental laws; addressing environmental issues of common concern. The CEC itself has a tripartite structure which includes a unique public advisory committee. While acknowledging that the CEC gets mixed reviews from the environmental community, Ms. Ferretti outlined an activist trilateral work program in key areas such as transboundary pollution, trade-environment linkages, and environmental law enforcement. An ongoing weakness of the NAFTA institutions, as a recent performance review concluded, is that "thus far the trade agenda is operating on a very separate course of interests and business from the agenda of the environmental commission." However, the CEC does possess innovative mechanisms which allow citizen complaints to be brought forward for a factual determination. According to Ms. Ferretti, the three governments recognize that more has been accomplished in terms of environmental cooperation than in dealing with the complex and contested terrain of trade-environment issues. She indicated that the most interesting challenge to the CEC may be the most recent allegation, brought by a coalition of Canadian environmental and labour groups, that NAFTA’s chapter 11 investor-state arbitration process is jeopardizing its environmental objectives. This has triggered an internal examination between the CEC and NAFTA structures that will be a very important test case to watch. Turning to NAFTA’s labour side agreement, Mr. Peter Bakvis outlined a number of concerns expressed by the labour movement during the NAFTA negotiations: potential job and wage losses, weakening of labour laws, and erosion of social protection measures. The NAFTA agreement was strongly criticized for lacking any concrete reference to worker rights or social standards. Unlike the situation in Europe, NAFTA proposed integration with a developing country in which average salaries were barely 10% of Canadian levels. Matters had improved with the election of the Clinton administration, resulting in a complementary labour cooperation "side accord." The U.S. had also introduced an adjustment assistance program, though none was forthcoming in Canada. The North American labour commission which was set up is similar to its environmental counterpart in affirming some laudable principles. However, it lacks a public advisory component and suffers in comparison to European structures for defending economic and social rights. No common norms are established, and enforcement of existing national laws remains especially problematic in Mexico (where the purchasing power of the minimum wage has dropped 30% since 1994). Mr. Bakvis argued that the complaints procedures are also narrow and weak, with violations of certain key rights – i.e., freedom of association, collective bargaining -- being subject only to consultations among NAFTA governments. Accordingly he recommended strengthening these structures by: incorporating obligations to adhere to core international labour rights (specifically seven fundamental conventions of the International Labour Organization); making non-compliance subject to sanctions; and establishing regular consultative mechanisms with NGO, labour and business representatives. Michelle Swenarchuk returned the focus to the environmental and health effects of a decade of FTA/NAFTA experience. Her prognosis was not optimistic, given her account of how successive trade treaties, notwithstanding considerable public opposition, have in fact circumscribed the grounds for public-interest protection. She cited several disputed cases (including a successful Canadian challenge of EU standards banning hormone residues in beef, and the U.S.-based Ethyl Corp.’s successful suit against Canada under the NAFTA investment chapter) to illustrate how in her view trade-biased interests have been allowed to prevail over other public-policy values in legislation – "We have seen this ever-enlarging number of areas of legitimate public policy where the deregulation of trade and the agreements are having the effect of blocking governments from taking legitimate action." Referring to French Prime Minister Jospin’s announcement of France’s withdrawal from the MAI negotiations, Ms. Swenarchuk observed the important difference between an inter-governmental delegation of sovereignty, as in the controlled framework of the EU, and the ceding of sovereignty to private international corporate interests. As for the structures of the international trade and trade-disputes system, she argued for much greater "transparency," including public rights of access, and also for effective parliamentary oversight and accountability. She was encouraged by the opportunities for Canadian-European alliances which could be developed to advance such a timely political and democratic reconsideration of the future direction of the trade regime. In the discussion period, responses to pointed questions from Mr. Davis confirmed the limited and uneven record of NAFTA institutions from a labour and environmental perspective, even if establishing cooperative mechanisms for both has been a step forward. Ms. Swenarchuk also observed in regard to the Ethyl case cited earlier that, regardless of the merits of the government’s strategy in defending itself against the lawsuit, the expansion of the concept of "expropriation" as defined in the NAFTA and proposed for the MAI exposes governments to growing private challenges to public-interest regulation as well as demands for compensation that exceed what would be acceptable under pre-existing domestic and international obligations dealing with commercial arbitration. Mrs. Durrieux, elaborating on French opposition to the MAI, concurred that such investor-state provisions have become imbalanced in favour of private versus public interests. Following up a question from Mr. Daniel Turp M.P. about the evolution of a "North American Community," referred to in recent speeches by Canadian foreign minister Lloyd Axworthy but as yet little debated publicly, there was a brief discussion of scenarios leading from NAFTA towards greater hemispheric integration along with negotiations [note: currently being chaired by Canada] on a proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). Mr. Bakvis observed that MERCOSUR, led by Brazil, envisages a process that is closer to the European integration model in its attention to the social dimension. Mr. Behrendt (Germany) wondered about the extent of NGO networking across borders in paying attention to environmental issues among others. And Mr. Gusenbauer (Austria) asked what should be the fate of the MAI. Ms. Swenarchuk indicated that strong links and social alliances, aided by the Internet, are developing among international NGOs. On the subject of free trade in the Americas, she argued that "the FTAA process will be used to implement the WTO agreements across the hemisphere and speed their implementation." On post-MAI options, she concluded that: "If it dies at the OECD, it will resurface at the WTO"; however, she agreed with many others who "always have been opposed to the WTO encroaching further into national sovereignty by negotiating an investment regime." Panel 3 "Social and Cultural Aspects of NAFTA" Speakers:

Professor Brooke Jeffrey began by observing some fundamental differences between the chosen paths of NAFTA and EU integration. In the case of the former, there had never been any intention of combining political and social with economic integration. She said Canadians especially are concerned with preserving national identity, and referred to the current government’s defence of measures to protect Canadian magazine publishers in the face of American challenges, raised by panel co-chair Senator Lorna Milne in her opening remarks. Within Canada, where provinces have important jurisdiction in social matters, there had been a vigorous debate over the effects of free trade, globalization, fiscal cutbacks, and other factors on social cohesion. But, unlike Europe, there was no framework at the NAFTA level for social policy considerations, much less any social agenda based on common values and goals. There is a NAFTA clause which allows each country the right to adopt any measures with respect to social services established for a public purpose. However, this reservation is of arguable force and has yet to be clearly tested in a dispute-resolution case. Indeed it is difficult to measure social effects, for good or ill, as being directly attributable to NAFTA. Taking a broader outlook, Ms. Jeffrey suggested that positive civil-society coalitions are nonetheless beginning to emerge among the three countries. Moreover, there appears to be a convergence among the value-sets of the region’s citizens (with Canadians putting the highest value on "tolerance," Americans, on "independence," and Mexicans, on "responsibility"), although such harmonization also seems due mainly to global influences not NAFTA. If citizens as well as elected officials are able to interact and participate more in a NAFTA context, perhaps we will see a growing basis and opportunity for advancing social-charter type concerns in years to come. Keith Kelly observed a similar difficulty with trying to measure NAFTA’s impact on Canadian culture. He also suggested that the ongoing focus on Canada’s "cultural exemption" obtained in the FTA/NAFTA may be somewhat misplaced, since a decade of experience has revealed plainly that such provisions offer scant protection – "the cultural exemption only works if the Americans decide to respect it." In fact, they have shown no sign of letting up on their right to retaliate against what they consider to be discriminatory Canadian cultural measures, and recently (as in the magazines case) they have been able to appeal to the WTO, in which "there are no cultural filters for the dispute settlement mechanism to use to treat a cultural dispute any differently than it would a dispute in traditional trading commodities." On a positive note, Mr. Kelly referred to international networking taking place, notably with European counterparts, to develop alternative formulations (such as the concept of a "charter of global parallel rights" in the area of culture) which can lead to durable solutions that preserve autonomous cultural expression within a beneficial global trade and investment environment. As he concluded: "We certainly hope that the international consensus on culture will develop to the point where we might be successful during the [WTO] millennium round at finding a solution to the issue of how we protect those values that are most important to us as nations." David Crane saw the impact of the FTA/NAFTA on socio-cultural trends as being linked to developments in the Canadian economy being driven by the dynamic evolution of international business activities and emerging communications technologies. He pointed to the actual or prospective entry of U.S. private service-providers in a number of areas – e.g., health, education, corrections -- which have traditionally been the preserve of the public sector. The larger context of globalization also in his view constrains governments’ ability to raise taxes to finance social objectives. In Canada’s case, cultural objectives will also be at stake in forthcoming WTO negotiations, notably in the services area, and probably getting underway in the year 2000 following the ministerial summit which the U.S. is hosting in late 1999. Reinforcing comments by Mr. Kelly, Mr. Crane observed that Canada must be creative as well as vigilant in developing realistic options with like-minded countries, since the U.S. has signalled its contrary determination to make cultural industries further subject to general trade rules, and not to grant culture any special status. Mr. Crane suggested that both Canadian and Europeans could do a better job of building alliances in the face of such American challenges. What Canada is seeking is not to restrict the cross-border flow of cultural products (indeed much of the Canadian consumer market is dominated by foreign culture), but to maintain "viable space for Canadian cultural industries to profitably serve the Canadian public" across the full range of media. In Mr. Crane’s view, the commercial aspect of this is critical to the survival of Canadian media, which do not enjoy the huge domestic market and economies of scale of their American competitors. Unfortunately, he contended, the FTA/NAFTA provisions have done nothing to shield Canadian culture from U.S. challenges and threats of retaliation. So if NAFTA evolves further in the direction of deeper integration, there is cause for worry. And, as fast-developing modes of electronic commerce and the Internet create new implications for culture and trade, Canadians and Europeans need to find ways of working together on what promises to be one of the most critical issues of the next WTO round. Leading off the discussion period, Mr. Caccia asked how it has come to pass that commercial and trade-driven considerations seem to dominate so much of international relations and diplomacy, to the detriment of social values. Can this powerful trend be constrained? In response, panellists referred to the profound effects of both a technological revolution and an ideological revolution in favor of de-regulation and privatization. Mr. Crane argued that, while it is not realistic to return to some traditional protectionist past, there are elements of a "counter-revolution" in the making. Governments are not powerless by any means, and there is increased attention to addressing "democratic deficits" at a number of levels. In the wake of the Asian financial crisis, even institutions like the IMF are recognizing that "global financial deregulation may have gone too far." The dilemmas of globalization and "global governance" are now a major topic of discussion in international fora. On culture and free trade, Mr. Davis said he understood Canadian worries about the overwhelming influence of American television and film, but queried whether Canadian defences of the domestic magazine industry were not simply subsidizing publishers’ profits, some of dubious merit. Mr. Kelly and Mr. Crane elaborated on reasons why so-called "split-run" editions of U.S. magazines threaten the viability of smaller Canadian publishers. Mr. Jan Figel (Slovakia, Chair of the Subcommittee on International Economic Relations), contrasted the NAFTA drive for competitiveness with the principle of solidarity which has guided the construction of a multinational European community in the post-war, and now post-Cold War, period. He asked: "Is there any institutionalized vision for solidarity in North American relations and NAFTA in particular?" Mr. Crane replied that there was none. The Clinton administration did create a North American Development Bank to get NAFTA passed through Congress, but as it dealt only with U.S.-Mexico border projects, Canada declined to participate. Lately, Foreign Affairs Minister Axworthy has been promoting the concept of a North American Community (see an earlier reference in Panel 2 and also background Note # 7), which appears to be primarily focused on education. However, Mr. Crane was doubtful about this initiative, especially given the Canada-U.S. philosophical differences over social and cultural policy. [*Note: in a recent essay comparing North American and European patterns of "continental" integration, Canadian international relations scholar Stephen Clarkson offers an insightful perspective on the transatlantic possibilities arising out of an emerging "NAFTA-EU axis."(1)] Other interventions pursued the issue of the design of evolving trade arrangements, and how the rights of governments would be affected; for example, Clifford Lincoln M.P. cited the undue power of big U.S.-based corporations as manifested in the Ethyl case and in the cultural field. Mr. Crane returned the onus to the governments which, after all, negotiate and agree to these trade deals -- "governments have more power than they like to think they have." Continuing on the subject of social and cultural consequences, Mr. Gusenbauer questioned the merits of a transatlantic marketplace "more or less functioning on the basis of NAFTA terms. (… ) If NAFTA terms do not offer better social and environmental possibilities, why start to negotiate at all? If it is not better than the WTO, what is the comparative advantage?" In struggling with this question, panellists agreed that international negotiations around such issues will be extremely difficult. On the cultural issue, which is also a major problem for Europe, making any progress will depend on changing the attitude of the United States. In emphasizing this point, Mrs. Francine Lalonde M.P. followed up an earlier query about the future of cultural "exemptions," and described this as a challenge which Canada shares with all European countries, not just those in the EU. Mr. Kelly was not optimistic about change in the U.S. bargaining position, but nevertheless strongly urged that Canada work closely with like-minded countries through the WTO process to achieve practical proposals for safeguarding cultural objectives. In bringing the discussion to a close, Mr. Caccia wondered about the efficacy of adding new social or cultural clauses into trade agreements in light of the unimpressive record of the NAFTA labour and environmental commissions to date. Mr. Gusenbauer also questioned the "soft language" that tends to get used in dealing with such problems of the trading system: "When it concerns profits, there is strong weaponry, but when it concerns fundamental human and social rights, we talk in terms that are very cloudy." Mr. Davis pointed out that the European Union does at least have a more enforceable supranational framework through the European Convention of Human Rights. In a final comment, Dr. Jeffrey observed the difficulty of getting the U.S. to accept such multilateral jurisdiction, and more generally, of negotiating social issues among such disparate partners. NAFTA remains a very limited instrument in this regard, and the EU will likely also be challenged by similar problems in its negotiations with Mexico and other Latin American partners. At the same time, both Mr. Kelly and Mr. Crane held out hope for carrying forward forms of intergovernmental cooperation – specifically, Canadians and Europeans working together on some of these issues -- that can make a real difference in how this new era of global commerce and enormous technological change is managed in ways that promote rather than undermine important societal and cultural values. Looking beyond NAFTA, this aim now has to be regarded as a crucial part of the transatlantic and the global challenge facing Canada and Europe into the new millennium. CANADA

AND THE EU: TOWARDS A TRANSATLANTIC The second day of the seminar turned the focus from the NAFTA experience to a discussion of current and future Canada-EU relations in view of the need for a strengthened transatlantic commercial relationship. Improving existing bilateral ties in specific areas is a key consideration, as was brought forward by parliamentarians who spoke both in the morning sessions held at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and the closing session on Parliament Hill. Beyond this is the question of how to build more effective bridges between North America and Europe, -- and perhaps to go as far as the construction of a Transatlantic Free Trade Agreement (TAFTA). Session 1 "Highlights of Canada-Europe Trade and Economic Relations" Speakers:

After introductions by co-chairs Mrs. Francine Lalonde M.P. (Vice-President, Canada-Europe Parliamentary Association) and Mr. Jan Figel (Slovakia, Chair of the Subcommittee on International Economic Relations), Ambassador Juneau led off with an upbeat portrait of the current state of Canada-EU relations. Among the optimistic characteristics of the relationship which he presented were the following:

Maintaining this positive perspective, Ambassador Juneau pointed to even more prosperous transatlantic links in the future, including services trade. Science and technology is another strongly performing area. In his view as well, the introduction of the Euro would enhance Canadian trade through a reduction in exchange-rate risk as well as indirectly through the beneficial impacts of European economic and monetary reforms. Moreover, as the EU will enlarge over the long-term, so too will Canada-EU economic relations, aided by longstanding Canadian trade ties with some of the candidate countries. Mr. Juneau expressed confidence that Canada can look forward to a strong economic partnership with an EU market that is already the world’s largest. At the same time, Canada has to continue to work hard to achieve improved access to the EU market through mutual recognition agreements and other means. Canada-EU economic links will grow even stronger as the barriers to trade are removed. From the European side, Mr. Alfred Gusenbauer argued that the future of Canada-EU relations depends largely on global market conditions. There was certainly a need for regional relationships within this global setting; to that end, the transatlantic marketplace could play a key role, but would have to be considered carefully on its merits. The issue of how to combine multiplying regional trade pacts with an overall multilateral approach came up at several points during the day’s discussions. In addition to the various trade talks between the European Union, NAFTA countries, and other Latin American countries, notably the MERCOSUR bloc, the co-chairs of this session, Jan Figel (Slovakia) and Mrs. Francine Lalonde M.P., also made reference to Canada’s launch of negotiations with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the Central European Free Trade Area (CEFTA) initiative. Such trade questions, Mr. Gusenbauer insisted, must be considered against the backdrop of some fundamental political and governance challenges confronting the global economic system. In order to deal with the current international financial instability, he called for changes to take place with respect to international institutions – in essence, a new Bretton Woods arrangement. In particular, he sought more coordinated global currency arrangements and was of the opinion that the move to a single, stable currency in Europe could help to ensure greater global stability. Mr. Gusenbauer went on to register his support for the WTO’s "Millennium Round," but noted that a truly comprehensive round of trade and investment talks would need to be launched. Mr. Gusenbauer argued forcefully that "democracy is a main and essential prerequisite for the development of a market economy that takes into consideration wealth, growth and development." Accordingly, the trend towards greater globalization must also be accompanied by increased democratization. Too much decision-making power was being left in the hands of corporations or international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank; legislators needed therefore to make their voices more influential and to make their governments more accountable for the actions taken by these organizations. This view was shared by other seminar participants, particularly Mr. Povilas Gylys (Lithuania), Mr. Wolfgang Behrendt (Germany), and Mr. Benoit Sauvageau (M.P., Canada). Mrs. Helle Degn (Denmark), Chair of the Council of Europe Assembly’s Economic Affairs Committee again emphasized the point in her remarks at the conclusion of the morning’s second session. The discussion period also raised a number of questions about the actual state of progress in developing Canada-Europe trade prospects. Senator Jerahmiel Grafstein noted that Canadian trade with continental Europe (in percentage terms) was on the decline, and that an acceleration of the Canada-EU Action Plan was being met by a lukewarm response in Brussels. Would not the creation of a transatlantic free-trade zone inject some dynamism into this situation and serve as well as a useful first step in the achievement of multilateral trade liberalization at the WTO? Responding to that observation, Mr. Gusenbauer queried whether such a "transatlantic marketplace" would necessarily be in Canada’s interest: "Have you analyzed the effects the transatlantic marketplace will have on Canada specifically?" He wondered whether in a new transatlantic arrangement EU companies would not be more inclined to deal with U.S. firms than with those of Canadian origin. Prompted by a question from Mr. Terry Davis (United Kingdom) on the extent of progress achieved on the Canada-EU Action Plan, Ambassador Juneau pointed to a number of bilateral agreements already entered into (e.g., on standards, customs, science and technology). According to Mr. Juneau, it is possible that more progress has been made in Canada than in the U.S. on their respective Action Plans. However, given the U.S.-EU bilateral trade discussions [note: which subsequently resulted in a Transatlantic Economic Partnership Action Plan being adopted on November 9], he also acknowledged that:

It also came out that there have been problems and delays in completing the Canada-EU Joint Trade Study envisaged in the 1996 Action Plan to identify trade barriers. Ambassador Juneau nevertheless maintained that Canadian policy is on course. In his view, in the absence of any framework that would allow a collective NAFTA-EU negotiation to go forward, the best approach is to carry on with existing bilateral efforts, at the same time looking out for where there might be possibilities for convergence or for a simultaneous trilateral negotiation with the Americans and the Mexicans. [*Note: On 2 December 1998, in a comprehensive presentation of Canadian trade policy and objectives leading into prospective WTO negotiations, Canadian International Trade Minister Sergio Marchi reiterated his view before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade that the aim of a Canada-EU partnership should be that: "when Europe looks to North America it sees a NAFTA community not just three different neighbourhoods." Canada’s clear preference, he argued, is that "Europe should be seen to be negotiating with all three of us at the same time."] Session 2 "Sectoral Issues and Areas for Future Bilateral Agreement" Speakers:

Co-chairs, Ms. Aileen Carroll M.P. and Mr. Roy Cullen M.P., introduced the session by highlighting some of the challenges and opportunities for Canada in progressing beyond historic trading patterns towards more diversified and dynamically expanding market relations with European partners. As Ms. Carroll asserted: "The principal growth industries are financial services, knowledge-based industries and environmental technology. Trade irritants involve primarily transactions in primary products. Consequently, it behooves us to focus on bilateral trade initiatives in those growth sectors which are not encumbered by unresolved trade irritants." Mr. Cullen noted the reservations expressed in the previous day’s panels about whether NAFTA, given some of its inherent problems, "really was the template for transatlantic trade." As well, he urged giving attention to issues of anti-corruption and economic crime which are crucial to improving business prospects in central and eastern Europe. Jason Myers focused his remarks on the structural changes that have taken place across Canadian industry since the advent of freer North American trade and which include a move to greater product specialization, corporate integration, and improved cost efficiency. Increasingly, firms are assuming world product mandates, albeit still with a decidedly U.S. focus. According to Mr. Myers, what this means in practice is that the economic growth resulting from free trade in North America is driving Canadian companies to satisfy a sizeable portion of their skilled labour, technology and information requirements from other regions such as Europe. Canada is also attracting increasing amounts of investment from European sources. He therefore cautioned the audience about adopting a strictly bilateral approach to the trade liberalization and business opportunities that are available. Rather, businesses need to take advantage of the global marketplace and discussions surrounding transatlantic trade need to mirror those at the global level. John Colfer’s presentation vigorously supported the successful conclusion of strengthened bilateral agreements between Canada and the EU to attain more compatible tariffs, to eliminate non-tariff barriers between the two entities, and to improve the transatlantic investment climate. He also pointed to the "information deficit" that small and medium enterprises (SME) faced regarding international business opportunities, but was optimistic that the federal government was starting to address the situation. Mr. Colfer also echoed the views of Canadian Trade Minister Marchi in expressing his belief that "community-to-community negotiations for fairer, more balanced bilateral agreements are fundamental to long-term benefits for Canada and the EU. Such agreements would allay fears of protectionism which come about as a result of separate negotiations between the EU and the U.S. and the E.U. and Mexico and could serve to stabilize world trade." In response to a comment by Mr. Caccia on the merits of entering into a TAFTA-type arrangement, Mr. Davis described how little enthusiasm there was in Europe for the idea. Later, in the afternoon session, he elaborated by saying that in the European mind, "transatlantic marketplace" refers to an EU-U.S. axis; in other words, one dominated by Brussels and Washington, and not including Ottawa. On the other hand, Mr. Davis was quite interested in the status of the Canada-EU Joint Trade Study now in progress. Ambassador Juneau revealed that the release of the document was being delayed by an inability to arrive at common conclusions regarding the most appropriate approach to trade liberalization. Owing to this impasse, the Ambassador foresaw the eventual publication of a separate Canadian, as opposed to a joint, document. A concluding comment from Mrs. Degn revealed some of the challenges which need to be overcome if the current trade discussions are to move to a higher level:

Closing Session "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic Marketplace" Speakers:

Senator Allan MacEachen launched the final session of the seminar by putting Minister Marchi’s recent comments about the construction of a more inclusive transatlantic relationship within the context of a useful historical perspective on Canada’s economic relations with Europe. He noted that the 1976 Framework Agreement on Commercial and Economic Co-operation between Canada and the EU was a product of the economic nationalism in vogue in Canada at the time. The attempted diversification of Canadian economic activities away from the U.S. (towards Europe and elsewhere) became known as the "Third Option"; the first two being the status quo, and increased integration with the U.S. But, even though "the prime minister made a huge investment in the European opening…. Nothing much happened in terms of revolution, at least in our commercial policy, for a long time." Mr. MacEachen went on to observe that the forces driving closer Canadian economic integration in North America certainly distracted Canada from Europe throughout much of the 1980s. The Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) which ushered in an historic policy shift was then furthered consolidated by the NAFTA. Nonetheless, attempts have been made during the current decade to bolster what some saw to be a flagging Canada-Europe relationship. These have had difficult moments; notably the "chilling effect" of the fisheries dispute between Canada and Spain. Canada has had to learn that "faced directly with the economic power of the European Union, we were not in an advantageous bargaining position." Mr. MacEachen suggested that, whereas in 1976 Canada was seeking European support to attenuate U.S. economic dominance, now the converse might be coming true. Although the political climate at present is not propitious for Prime Minister Chrétien’s proposed TAFTA, its time may yet come (as far back as the 1950s Lester Pearson put forward the idea of a North Atlantic trade agreement); "patience is required." In the meantime, important benefits can still be seized by Canada through both the bilateral efforts already described – which should include both old and new friends within the European family of nations -- and the new multilateral round of trade talks. Mr. MacEachen closed by remarking that in a period of high turbulence, such as we are experiencing in the wake of the Asian crisis, problems must be addressed both by getting "the domestic fundamentals correct" and "by a profound debate about the operation of the international financial system and the implications of enthusiastic applications of globalization." Mr. Terry Davis (former Chair of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Committee on Economic Affairs and Development) was blunt in throwing cold water on the current prospects of a TAFTA. In his view, the construction of only one bridge across the Atlantic (TAFTA versus three separate bilateral processes), although preferable, is very doubtful in reality because "I do not think that the United States government is going to accept it." He observed that: "When politicians in Europe talk about transatlantic, they really mean United States of America. That is an extremely important point that Canadians and Mexican need to appreciate." Ambassador Juneau had appreciated that in his morning presentation. The fact is that the central negotiating path will be directly between the U.S. and the EU towards a new bilateral relationship between the two economic superpowers. This strengthened relationship would then set the stage for a common approach to the 1999 multilateral discussions at the WTO. In fact, Mr. Davis’ prophecy has already come to pass. As the introduction to these summary highlights has already pointed out, a new "Transatlantic Economic Partnership" (TEP) Action Plan between the two economic giants was agreed to in November 1998. Mr. Davis ventured that it might be more useful for Canada to work closely with Mexico, rather than to seek to engage the U.S., in "trilateralizing" a relationship with the EU: "If I were a Canadian Member of Parliament, I would be pressing for trilateral discussions, given that America will not allow it to be quadrilateral, but the third party would be Mexico rather than the United States." He also offered an incisive comment on the TEP proposal (since adopted):

At the same time, Mr. Davis argued forcefully that Canada is not without options of its own. He advised Canada to use its bilingualism to advantage in Brussels and to "try to cultivate some new friends and look to the future rather than to the current situation… not just to Germany (the example of bilateral ties cited by Mr. MacEachen) but also to the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and some of the others who will be in the European Union but in the meantime share the same feelings that you have about being left out of the discussions." Mr. Davis regretted the delay in putting out the planned Canada-EU Joint Trade Study since, as he put it: "If your friends at the Council of Europe want to defend your interests inside the European Union and in the rest of Europe, then your friends need to know the facts." In the wrap-up, there was further emphasis on forging alliances that cross the Atlantic, not only to promote trade and wealth creation, but in socially-conscious ways that, in Mr. Figel’s words, help "to build a real community of values." Mr. Gusenbauer observed that the "realpolitik" of U.S. dominance ought not to diminish the successes of Canadian diplomacy. Mr. MacEachen mentioned his first hand experience that, when dealing with its superpower neighbour, Canada has sometimes been freer than its European counterparts. From the European side, Mr. Gonzalez-Laxe (Subcommittee rapporteur for the seminar) expressed satisfaction with the rich record of the two days of discussions; in particular the thought-provoking questions raised about NAFTA’s future evolution, the need to develop institutional and parliamentary frameworks for managing common transatlantic economic interests, and the choices facing Canada in navigating between the economic superpowers of the EU and the U.S. From the Canadian side, Mr. Caccia was grateful for the contributions of all participants and, noting in particular the frank interventions by Terry Davis, reaffirmed a Canadian dedication to some day turning the "elusive policy goal" of a transatlantic "third option" into a reality. PROGRAMME CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE PARLIAMENTARY SEMINAR "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic Marketplace" OTTAWA, 19-20 OCTOBER 1998 Monday October 19, 1998 - Day 1 "CANADA’S NAFTA EXPERIENCE" 8:00 – 8:30 Registration 8:00 – 8:20 Formal

Convocation COE Economic Affairs Subcommittee 8:20 – 8:45 Opening Statements 8:45 - 10:30 Panel 1 "Trade Issues

and the Dispute Resolution Mechanisms" Chairperson(s):

Panellists:

10:30 – 10:45 Break 10:45 - 12:30 Panel 2 "Labour and

Environmental Aspects of NAFTA" Chairperson(s):

Panellists:

12:30 - 14:00 The Hon. David Michael

Collenette 14:00 - 15:15 Question Period in House of Commons 15:30 - 17:30 Panel 3 "Social and

Cultural Aspects of NAFTA" Chairperson(s):

Panellists:

18:00 Reception for participants Room 256-S Tuesday October 20, 1998 - Day 2 "CANADA AND THE E.U: TOWARDS A TRANSATLANTIC MARKET PLACE" 9:00 - 10:30 Session 1 Highlights

of Canada-Europe Trade and Economic Relations Chairperson(s):

Panellists:

10:30 – 10:45 Break 10:45 – 12:15

Session 2 Sectoral Issues and Areas for Future Bilateral Agreement Chairperson(s):

Panellists:

12:15 – 12:30 Mrs.

Helle Degn (Denmark) 12:30 – 13:45 Working Lunch with Keynote Address by Honourable John Manley Minister of Industry Lester B. Pearson Hospitality

Centre (Department of Foreign Affairs) 13:45 – 14:00 Shuttle Back to Parliament Hill 14:00 - 14:30 Question Period in the Senate 15:00 – 17:00

Concluding Session: "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic

Marketplace" Chairperson(s):

Speakers:

17:00 Closing Remarks

18:00 Reception

sponsored by the Canada-Europe Parliamentary Association and the National

Capital Commission BRIEFING

NOTES FOR CANADA-COUNCIL OF EUROPE On 19-20 October 1998 a Canadian parliamentary seminar was held on the theme "Beyond NAFTA to a Canada-Europe Transatlantic Marketplace," jointly sponsored by the Canada-Europe Parliamentary Association and the Sub-Committee on International Economic Relations of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly’s Committee on Economic Affairs and Development. Forty countries now belong to the Strasbourg-based Assembly, Europe’s oldest body dedicated to the aims of democratic and social solidarity, which marks its 50th anniversary in 1999. National parliamentarians from all 15 member states of the European Union and from most central and eastern European nations, including Russia, participate in its quarterly sessions and committee activities. Canadian parliamentarians have had observer status in the Assembly since May 1997. The idea for this seminar developed out of European counterparts’ desire to learn more about the North American free-trade area from a Canadian perspective, and a reciprocal Canadian interest in exploring, in addition to the existing NAFTA, further options that could lead towards a broader transatlantic economic arrangement of mutual benefit to the increasingly-integrated North American and European regional blocs. Accordingly, the Canada-Council of Europe Parliamentary Seminar focused on these aims, with a view to stimulating a dialogue between Canadian and European counterparts that could point to common interests and options for advancing transatlantic economic relations. The first day’s panels addressed key dimensions of Canada’s evolving NAFTA experience. The second day was devoted to Canada’s commercial relations with Europe and prospects for developing closer transatlantic partnerships. Below is a slightly revised version of a series of briefing notes prepared by the Parliamentary Research Branch for seminar participants. The notes by Gerald Schmitz introduce the theme and cover many aspects of Canada’s evolving NAFTA experience, including the record of dispute resolution institutions, associated environmental and labour cooperation bodies, and the relationship to social and cultural policy issues. The notes by Peter Berg concentrate on Canada-European Union trade issues, both bilaterally and looking towards the prospects for a transatlantic free-trade area that would advance Canadian interests and be compatible with shared North American and European objectives at the global level. Included as well are selected references to other documentation sources and some related electronic links. DAY

ONE: CANADA’S NAFTA EXPERIENCE The following three sets of briefing notes for Day One of the Canada-Council of Europe Seminar, October 1998, review some of the most important aspects of Canada’s participation in NAFTA. The notes for Panel 1 explain the genesis of the agreement, its principal elements, and trends since its entry into force nearly five years ago on 1 January 1994. These notes also look at NAFTA’s dispute resolution mechanisms and the patterns of trade disputes involving Canada under the NAFTA regime. Going back to the early 1980s, a primary rationale for Canada’s pursuit of continental free-trade rules was to obtain security of access to U.S. markets. Although cross-border trade volumes have greatly increased, that objective has been at best only partially achieved. While promoting trade and investment flows is NAFTA’s chief purpose, the agreement also broke new ground through the attachment of two "side agreements" on environmental and on labour cooperation. The notes for Panel 2 outline the work of the commissions set up to implement these agreements and comment on the debate over the record of the NAFTA with respect to environmental issues and labour standards. NAFTA has also proved controversial in terms of perceived or potential impacts which could put at risk Canada’s system of social protections (e.g., public health care) and policies to safeguard culture. The notes for Panel 3 look at the NAFTA debate as it affects these areas of government intervention and democratic choice. TRADE ISSUES AND THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION MECHANISMS NOTE #1: THE NAFTA: ORIGINS, KEY ELEMENTS AND EVOLUTION (2) Canada took the crucial first step towards NAFTA when the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney decided to pursue bilateral free-trade negotiations with the United States in the mid-1980s. Although the talks nearly failed and the 1988 Free Trade Agreement (FTA) was extremely controversial, it provided the template for the subsequent development of continental free-trade arrangements. The FTA with the U.S.’s northern neighbour also spurred its southern neighbour, Mexico, to request its own free-trade negotiations in 1990. Three-quarters of Canadian exports were to U.S. markets but Mexico was nearly as dependent, with two-thirds of its exports destined for those markets. Strong geopolitical interests were also at stake. As those bilateral talks proceeded, Canada became concerned that FTA gains not be eroded, and that an outcome be avoided in which a U.S. "hub" would enjoy more advantages than the separate "spokes" of either free-trade partner. In early 1991 the negotiations were trilateralized at Canada’s request. Canada subsequently moved from a mostly defensive posture to a proactive stance open to the inclusion of new issues and a broader regional trade liberalization agenda. The trilateral process also meant that Mexico, despite its very different level of development and political system, had to accept reciprocal obligations comparable to those of the Canada-U.S. FTA if it wanted to be treated as an equal partner. Mexican President Salinas was committed to a market-driven economic development model which accepted the increasing internationalization of trade and investment flows and responded to the competitive pressures arising from transnational business strategies. Indeed, the NAFTA as a whole, which received its strongest support from business groups in the three countries, should be seen as part of a more general trend towards expanded market liberalization regionally and globally, with rules disciplining the behaviour of governments accordingly. By the end of 1992, the three governments had successfully concluded negotiations and signed a NAFTA agreement. However, by this time there was a new Democratic administration in the United States. The negotiation of additional parallel accords during 1993 – on environmental cooperation, signed in August and on labour cooperation, signed in September – was mainly motivated by President Clinton’s attempt to assuage American concerns over Mexican environmental and labour conditions. But, although Congress then narrowly ratified the NAFTA, a majority of Democrats still voted against it. By the end of 1993 Canada also had a new Liberal government with concerns about NAFTA, notably in regard to the continued application of U.S. trade-remedy laws (i.e., antidumping and countervailing duties on Canadian exports). A joint political statement agreed to establishing working groups on these irritants prior to the Canadian Parliament’s approval of NAFTA legislation. The treaty itself came into effect as scheduled on 1 January 1994. The NAFTA establishes a free-trade area among the three countries, not a customs union or common market, much less an economic union. This means that the parties to the agreement remain free to pursue distinctive trade policies towards non-member states; complex "rules of origin" determine which goods and services are sufficiently North American to qualify for preferential NAFTA market terms. There is little in the way of formal requirements to harmonize other economic policies, or adjustment mechanisms to deal with economic dislocations. Nor is labour mobility addressed, apart from some provisions to facilitate the temporary entry of business and professional persons in liberalized sectors. However, NAFTA is a very comprehensive and far-reaching treaty, extending the principle of "national treatment" – which obliges governments not to discriminate between domestic and foreign producers – further into areas of services trade, government procurement, and investment. NAFTA is designed to promote the freer regional movement of goods, services, and capital, and therefore accelerates competitive conditions in the three countries, except where it is explicitly stated that NAFTA rules do not apply. Among noteworthy features of the NAFTA are the following:(3)

The NAFTA is considerably more institutionalized than was the Canada-U.S. FTA. It is overseen by a Free Trade Commission composed of cabinet-level representatives, and there are also ministerial-level commissions governing implementation of the environmental and labour accords. Under the main Commission, there is a secretariat composed of national sections. A trilateral "coordinating secretariat" to assist the Commission’s work was established in Mexico City in late 1997. Below that, some 30 intergovernmental committees, working groups and other subgroups are active in following up various aspects of NAFTA provisions (see appendix 2 for a complete listing). The sufficiency of NAFTA institutions is debatable. According to Stephen Randall: "The failure under NAFTA to establish an umbrella organization which might take decisions buffered somewhat from the vagaries of domestic politics in any of the countries reflects the very traditional nature of the NAFTA agreement and the mutual jealousy of national sovereignty that exists among its members."(5) However, a recent report done for NAFTA’s Montreal-based Commission for Environmental Cooperation suggests that an extensive intergovernmental "NAFTA regime" is developing which "has shown clear signs of significantly altering the breadth, depth and path of cooperation among the three countries."(6) Some NAFTA critics have compared it unfavourably to European economic community institutions in its failure to adequately address social dimensions (see Note #6). However, adding social provisions to NAFTA would likely require additional transfers of sovereignty to the trilateral level, and would come up against complaints, which will sound familiar to European ears, that NAFTA rules are already too intrusive into areas of national jurisdiction and that NAFTA intergovernmental bodies are too technocratic and removed from democratic control. It seems clear that the NAFTA has boosted trade and investment flows within the North American region, and that there is Canadian reliance on those flows. Over 82% of Canada’s 1997 merchandise exports and over 70% of imports were with NAFTA partners; almost all of this accounted for by the $1.4 billion in daily cross-border commerce with the United States. By comparison, Canadian figures for trade with the EU are only 5% of exports and 10% of imports. Services trade with the U.S. is also over $50 billion annually. Trade with Mexico has increased 80% since 1993, but still accounts for less than .5% of Canadian exports, though imports from Mexico have grown to 2.5%. Investment flows among NAFTA partners have increased substantially to over $200 billion. Again, although Canadian investments in Mexico have multiplied, for Canada investment is primarily U.S.-oriented. U.S. investments account for about two-thirds of the total stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) into Canada. Government and business studies claim that NAFTA’s first years have been associated with positive job creation overall. However, labour organizations and other critics contend that the unemployed have not been helped and that thousands of good manufacturing jobs have migrated southward as a result of low-wage competition and corporate restructuring within an integrated North American market. Independent analysts have tended to discount claims of either large gains or large losses from the operation of the trade agreements.(7) Furthermore, notwithstanding increasing transnational economic integration, national borders still matter a lot in determining trade flows.(8) And, given the persistence of interprovincial barriers in the Canadian case, there is still work to do to liberalize internal trade flows. The ongoing political debate over NAFTA’s evolution and impacts is less on whether these are wealth-enhancing in the aggregate than on whether benefits and costs have been fairly shared, and whether the constraints put on government action are compatible with democratically determined values such as environmental protection and social health. For Canada, being able to preserve a distinctive cultural identity is also fundamental. Although NAFTA is open to accession by other countries, and Canada has favoured this for countries like Chile, there are strong domestic misgivings in each country about further free-trade expansion linked to social, environmental and other public-interest concerns. U.S. initiative has been hampered by the inability to renew congressional "fast-track" negotiating authority since 1994. Compared to the highly institutionalized trajectory of European integration, the NAFTA remains a very limited instrument for addressing such issues. Yet as integration processes become broader and deeper, the complications of the growing civil-society and values-based dimensions of emerging trade and investment regimes are becoming apparent – for example, in the current public debate over the MAI, and as Canada assumes the early chairmanship of hemispheric negotiations towards an eventual Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). In recent months, moreover, Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy has been promoting the concept of "building a North American Community" in response to evolving regional economic integration and global agendas (see also Note # 7).(9) With respect to future relations between the North American and European economic blocs, obviously there are still many differences between the two, and the NAFTA countries continue to pursue separate bilateral processes in their relations with the EU. Canada is also looking to negotiate a bilateral agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries.(10) However the dynamics of regional integration may yet produce more expansive opportunities for convergence. Several decades ago some had hoped that a different NAFTA – a North Atlantic Free Trade Area – might emerge. While that option never materialized, and while recent ideas proposing a TAFTA (Transatlantic Free Trade Area) face many hurdles, few would contest the desirability of deepening the transatlantic economic connection. The question is: how to do this, given current NAFTA and EU realities?(11) Canada is also on record as favouring a movement towards a "community-to-community" transatlantic economic arrangement that would be good for each bloc as well as consistent with momentum for global trade liberalization (see Note #9).(12) Even if present circumstances are not propitious to such a concept, it merits serious consideration. As a Canadian ambassador with experience on both sides of the Atlantic recently observed:

THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE NAFTA A. Tariffs

B. Rules of Origin

C. Investment

D. Services

Source: Anthony Chapman, North-American Free Trade Agreement: Rationale and Issues, Background Paper 327E, Parliamentary Research Branch, Ottawa, January 1993. E. Financial Services

F. Government Procurement

G. Land Transportation

H. Telecommunications

I. Agriculture

J. Review of Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Matters

K. Institutional Arrangement and Dispute Settlement Procedures

L. Automotive Trade

M. Textiles and Apparel

N. Energy and Basic Petrochemicals

O. Other Measures

Source: Anthony Chapman, North-American Free Trade Agreement: Rationale and Issues, Background Paper 327E, Parliamentary Research Branch, Ottawa, January 1993. NAFTA’S INTERGOVERNMENTAL BODIES FREE TRADE COMMISSION (FTC) NAFTA Coordinating Secretariat FTC Secretariat Committee on Trade in Goods Working Group on Rules of Origin

Committee on Trade in Worn Clothing Committee on Agricultural Trade

Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards Technical Working Group on Pesticides Trilateral/Bilateral Working Groups adopted from Canada-US FTA

Committee on Standards-Related Measures Land Transportation Subcommittee

Working Group on Government Procurement Committee on Small Business Financial Services Working Group on Trade and Competition Policy Working Group on Temporary Entry Advisory Committee on Private Commercial Disputes Working Group on Emergency Action Working Group on Subsidies and Countervailing Duties Working Group on Dumping and Antidumping Duties Working Group on Investment and Services COMMISSION FOR ENVIRONMENTAL COOPERATION (CEC) CEC Council CEC Secretariat Joint Public Advisory Committee (JPAC) National Advisory Committees COMMISSION FOR LABOR COOPERATION (CLC) CLC Council CLC Secretariat National Administrative Offices (NAOs) National Advisory Committees REVIEW PROCESSES Long-term review process – Automotive Long-term review process – GATT/WTO NAFTA-INSPIRED INSTITUTIONS Energy Efficiency Labelling Group Health Group Transportation Consultative Group Border Environment Cooperation Commission North American Development Bank Source: NAFTA’s Institutions: The Environmental Potential and Performance of the NAFTA Free Trade Commission and Related Bodies, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, Montreal, 1997, Appendix A, p. 67-69. NOTE